The greatest aircraft carrier battle of all time devolved into a one-sided slaughter in which Japanese attackers served as little more than targets.

“Vector 245 degrees, distance 60 miles.” The message from USS Essex’s combat information center crackled through the radio of Air Group 15 commander David McCampbell. He was leading 10 Grumman F6F-3 Hellcats of VF-15 at 25,000 feet, looking to intercept another approaching swarm of Japanese attackers—one of the many desperate raids the enemy would fling at the U.S. Navy west of the Mariana Islands on June 19, 1944.

Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher’s Task Force 58 (TF-58)—a huge armada of 15 fleet aircraft carriers and escorting battleships, cruisers and destroyers—had closed on the Marianas a few days earlier. The flattops carried more than 900 warplanes: Hellcats, Grumman TBF/TBM Avenger torpedo bombers, new Curtiss SB2C-1 Helldivers and a few of the old, reliable Douglas SBD-5 Dauntless dive bombers. In the van of this great fleet was a landing force of eight escort carriers, transports and escort vessels, intent on seizing Japan’s mid-Pacific bastions—Saipan, Tinian and Guam.

The Japanese had controlled Saipan, Tinian and Rota since 1914, and the American territory of Guam since the December 1941 invasion. More than 600 Japanese aircraft were based on the four islands, along with a garrison of some 62,000 troops. The strategic Marianas were just 1,300 miles south of Japan’s Home Islands. Their seizure would leapfrog Allied forces past Japanese bases in the Caroline Islands and flank the occupied Philippines to the west. Thus it seemed extraordinary that units of the Imperial Japanese Navy were so slow to react to the Marianas menace. TF-58 began the pre-invasion pounding of Saipan and Tinian and the reduction of their air defenses on June 11, but it was not until the 13th that Vice Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa sortied the Japanese Combined Fleet from bases in Borneo, 1,000 miles distant.

By then Japanese air strength in the Marianas had been mauled on the ground or in the air (more than 120 aircraft destroyed in two days), and U.S. Marines had landed on Saipan on June 15. Still, a few remaining serviceable Japanese planes from the Marianas and others flying from distant bases sought to interfere, only to be summarily dispatched by vigilant TF-58 air patrols.

Ozawa’s task force numbered nine carriers and escorts, with about 450 aircraft. But the problems of defending far-flung islands, as well as years of attrition among its veteran aircrews, had left the Combined Fleet at a disadvantage in numbers and quality. As the Japanese groped their way toward Mitscher’s fleet, they were sighted and shadowed by patrolling U.S. submarines.

The battles that ensued on June 19-20 involved hundreds of aircraft in what most consider history’s greatest carrier-versus-carrier engagement—before or since.

Commander McCampbell’s 10 Hellcats identified Essex’s radar plot at a distance of two miles 5,000 feet below them—some 50 Mitsubishi A6M5 Zero (or Zeke) fighters and Yokosuka D4Y1 Judy dive bombers. It was but one of many raiding forces intent on the destruction of the American carriers.

McCampbell’s after-action report described the engagement:

Immediately upon sighting the enemy formation a high speed closing approach was initiated by nosing over and converting altitude advantage to speed. The initial attack was commenced in the form of a high-side, high-speed run, by sections in formation, while four planes retained altitude and acted as top cover according to doctrine.

My first target was a Judy on the left flank and approximately half way back in the formation. It was my intention, after completing this run on the plane, to pass under it, retire across the formation and take under fire a plane on the right flank with a low side attack. These plans became upset when the first target blew up, practically in my face, and caused a pullout above the entire formation. I remember being unable to get to the other side fast enough feeling as though every rear gunner had his fire directed at me. My second attack was made on a Judy on the right flank, which burned fiercely and fell away out of control.

My efforts were directed towards retaining as much speed as possible and working myself ahead and into position for an attack on the leader. A third pass was made from below rear on a Judy which was hit and smoking as it pulled out and down from the formation.

Retirement was made up and to the side which placed me in position for an above, rear run on the Japanese leader, closely formed with his port wingman, the other wingman trailing somewhat to the right rear. After my first pass on the leader with no visible damage observed, my pullout was made below and to the left. Concentrating on the port wingman, my next pass was an above rear run from 7 o’clock, causing the wingman to explode in an envelope of flame.

Breaking away down and to the left placed me in a position for a below rear run on the leader from 5 o’clock. I worked on his tail until he burned furiously and spiraled downward out of control. During my last bursts on this formation leader I experienced gun stoppages.

After charging his guns and noting that VF-15 had decimated the formation, McCampbell pursued a second, lower formation of Japanese dive bombers: “A Judy that apparently had been leading, offered itself as a target. I made a modified high side run and only my starboard guns fired which threw me into a violent skid and an early pullout was made after a short burst. Guns were charged twice again and since my target had pushed over and gained high speed, a stern chase ensued. There were short bursts of my starboard guns alone before they ceased to fire. The Judy pulled up into a high wingover before plummeting into the sea. Neither the pilot nor the rear-seat man attempted to parachute. While witnessing this crash I attempted to clear the gun stoppages without success and assumed that all ammo had been expended.”

The VF-15 Hellcats had broken that attack, downing 21 enemy aircraft with three probables. Dave McCampbell had destroyed five himself. One Hellcat pilot was missing in action. Circling to the north, avoiding the AA umbrella that the warships had spread over the fleet, McCampbell witnessed a Japanese bomb hit South Dakota. It resulted in some 30 casualties, but the battleship ploughed forward majestically.

“One very vivid picture stands out in my mind,” McCampbell recalled, “that of many fires and oil slicks closely strung in nearly a direct line along the track of the enemy raid for a distance of 10-12 miles on the water.”

After landing, refueling and rearming, the VF-15 pilots took to the air again. On his second sortie McCampbell claimed two more kills near Guam.

The carrier Lexington also had its Hellcats in the thick of the fight over the fleet. Lieutenant Alex Vraciu of VF-16 was elated to find so many targets: “This is going to be a cinch, I thought, and still lots more were around. They were like a swarm of bees; they were so thick against the water below. I felt like a kid with a plate of cookies—afraid someone else was going to take some even though I had all I could stuff.”

Vraciu caught two of his victims near a U.S. destroyer that held its AA fire as he downed both attackers. “All flamed like gasoline-soaked tissue,” he recalled. Inside a furious 30-minute period Vraciu downed six Judys.

Ensign Walter Albert, also of VF-16, was in his first air battle. He pulled alongside a Japanese bomber, wanting to make sure of his target. “Sure enough I spotted his tail hook,” he reported.“Then I saw the rear gunner with his gun poking out at me. But he didn’t shoot. He just folded down that gun, pulled the canopy shut over him and shrank clear out of sight. I guess he was scared to death. Then I eased back on his tail and—b-r-r-p—down went the plane.” Albert also destroyed a Nakajima B6N2 Jill torpedo bomber within minutes of his first victory.

Lieutenant Zenji Abe’s flight from the carrier Junyo’s 652nd Kokutai (air group) was typical of the attacking Japanese units. His group contained both the new D4Y1 Judy and a few older Aichi D3A2 Val dive bombers escorted by Zeros. The 400-mile flight was intended as a oneway mission, to attack the American fleet and then land on Guam. “We were pursued persistently by four Grummans,” Abe related, “and I lost all of my subordinate planes in my sight and was alone. I escaped from their attack by taking advantage of scattered clouds and the superior speed of the D4Y. I ran out of fuel and could not avoid a forced landing on Rota.” Abe survived, but the Pearl Harbor veteran’s aircraft was destroyed in subsequent strafing attacks, and he was stranded on Rota until the end of hostilities.

A flight from Hornet’s VF-2 patrolling near Guam encountered many more approaching Zeros and Vals, low on fuel. VF-2’s Hellcats engaged the orphans and downed 20 along with several probables. Ensign Wilbur B. Webb was credited with six Vals destroyed and two probables, though his F6F-3 took considerable punishment from the rear gunners. Webb recovered aboard Hornet, but his Hellcat was so badly damaged that it was jettisoned.

At dusk the 13-hour onslaught against TF-58 finally subsided. Essex had launched a final flight of Hellcats led by VF-15’s Commander Charles W. Brewer. Airborne for his second time that day, Brewer encountered final stragglers from the Japanese attackers seeking haven on Guam. He led his unit into the traffic pattern for Orote airfield and began picking off Zeros. Brewer had just flamed his fifth fighter of the day, and his wingman, Ensign Thomas Tarr, had downed another, when a flight of Zeros from higher altitude shot down and killed both men. The remaining VF-15 pilots claimed eight more victories.

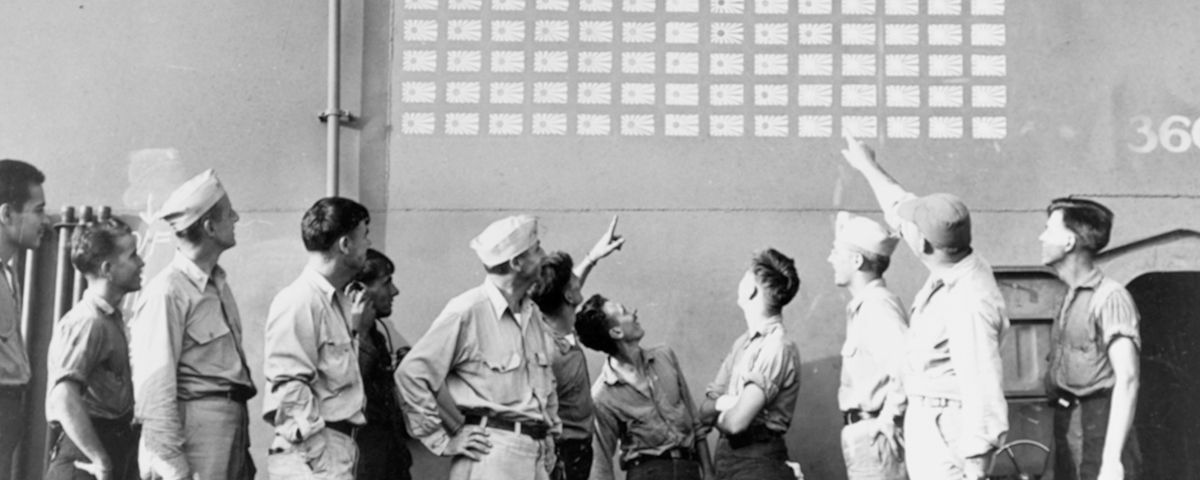

As the historic battle of June 19 ended, TF-58 had taken some physical punishment but remained intact. It had lost 18 fighters, 12 bombers and 27 airmen, a few to Navy flak. However, the Japanese had lost an astounding total of 429 aircraft, including attackers from Ozawa’s force and land-based planes from Rota and Guam.

In the VF-16 ready room on Lexington, Lieutenant Ziegel W. Neff reported his encounters to intelligence officers. He had downed a Jill around noon 60 miles from the task force and then, on a second mission in midafternoon, he bagged a lone Aichi E13A1 Jake floatplane and a pair of Zeros. Neff famously commented, “Hell, this is like an old-fashioned turkey shoot.” Barely 100 aircraft returned to the Japanese fleet.

The loss of so many carrier aircraft and crews was not the only disaster for the Combined Fleet. U.S. submarines Albacore and Cavalla, shadowing the Japanese, scored fatal torpedo hits on the carrier Taiho (Ozawa’s flagship) and Pearl Harbor veteran Shokaku.

Believing that he still had substantial air assets available in the Marianas, Ozawa (who had transferred his flag to the heavy cruiser Haguro) ordered the few remaining carrier planes and the shore-based survivors to have another go at TF-58 on June 20. Once again the Japanese lost many aircrews, with negligible results. Vals, Jakes, Kates, bomb-carrying Zeros, Jills and even twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M2 Betty bombers attacked in small gaggles or singly. Few could penetrate the defensive screen of anti-aircraft fire and F6Fs. Japanese pilots who avoided being torn up by flak or mauled by Hellcats made for Guam and Rota, only to find that the runways had been cratered by prior attacks. Crashed aircraft soon littered the airfields.

By mid-afternoon on the 20th, two Enterprise Avengers scouting far to the west located the balance of Ozawa’s fleet, and Lieutenants Robert Nelson and James Moore radioed the location. It was near 4:30, late in the day for a strike of some 250 miles’ distance, but Mitscher began launching his bombers and fighters. The strike force, numbering some 227 aircraft and heavily weighted to Hellcats carrying 500-pound bombs, bore west across the Philippine Sea toward a lowering sun. With only 75 minutes until sunset, the probability of the strike force returning in the dark raised the anxiety level throughout TF-58. Daytime carrier operations were dangerous, but night operations, especially in a war zone, were particularly perilous and rare. Only a few of TF-58’s air groups had practiced night landings.

The Americans sighted the Japanese fleet two hours and 300 miles later. Cumulus cloud buildups in the dusk made the approach more difficult. Some of the Helldivers went for the nearest ships, four fleet oilers, while the rest of the strike force concentrated on the carriers and warships surrounding them.

Japanese fighters quickly appeared, as Lt. Cmdr. James D. Ramage, CO of VB-10, recalled:“David J. Cawley [rear-seat gunner in the SBD] informed me of several Zekes on our port quarter. Each time they would commence a run our Air Group Commander [William R “Killer” Kane] would nose into them with the F6Fs. The Japanese would break off the attack, apparently deciding to wait until our most vulnerable time, the point of roll into the attack.”

As Ramage began his dive on the carrier Junyo, he heard Cawley firing his twin .30-caliber guns. “I looked over to the right and within five feet of me, passing below, was a Zero. The dive brakes had thrown him off his aim. My dive was a good standard 70-degree attack. At about 5,000 feet I opened up with my two .50-caliber machine guns, the tracers going directly into the forward elevator. The carrier was steaming directly into the wind. Allowing for wind and target motion, I moved the pipper to just ahead of the bow of the carrier and released at 1,800 feet.”

Ramage’s division of Dauntlesses, Avengers of VT-10 and Hellcats of VF-10 dived together toward the twisting Japanese ships. Don Gordon of VF-10 strafed Junyo’s port catwalk and saw three hits. “As we departed at very low altitude,”he reported,“I saw a Zero heading in the opposite direction about 500 feet above us. I pulled up with my wingman for an upside down overhead. It worked. My wingman fired when I did. The Zero blew apart and we completed our loop through the debris to rejoin the formation for the long ride home.”

Four TBMs from Belleau Wood’s VT-24 were the only Avengers carrying torpedoes. Led by Lieutenant George P. Brown, they dived through a blizzard of flak and fighters as they fanned out to bracket another Japanese carrier. The VT-24 fliers had to pass over the escorts’ blazing AA batteries to get within torpedo drop range of Hiyo. Brown’s Avenger was hit and seen to be on fire, but Hiyo took at least one torpedo and later sank.

The returning strike force, minus several planes that were lost in the raid, straggled through the darkness, homing on a signal from TF-58. Like kindred lost souls, aircraft of various units gathered together, gaining comfort in numbers. Some planes had better range than others, and some exercised better fuel economy measures. A few pilots who were low on fuel elected to ditch together.

Finally, finding TF-58 turned out to be easy. Per orders from Admiral Mitscher, the lights of the many ships plus some star shells fired by escorts made the fleet visible for 30 miles—a risky move given the possibility of Japanese submarines in the area. Fighters and bombers swarmed like bees returning to the hive, but crash landings were common and carrier decks were fouled for precious minutes. As their tanks ran dry, pilots landed on any carrier available. Lieutenant Commander Ramage of Enterprise brought his Dauntless down on Yorktown, where a plane director signaled him to fold his wings. (Avengers and Helldivers could fold their wings, but not the old SBD.)

Some of the airmen, including Commander Kane, CO of Air Group 10, ditched near destroyers. Returning to his carrier the next day, he admitted, “Everyone was running out of gas but I ran out of altitude.” He had flown into the water and had two black eyes and 13 stitches in his head.

Before the chaotic night ended, 79 aircraft had been lost: 17 in combat and the rest in the ocean or in carrier crash landings. Herculean search-and-rescue operations began immediately and extended west along the track of the attack even to the area vacated by the Japanese fleet. In a final accounting, the Navy had lost 16 pilots and 33 enlisted air crewmen.

Ensign Cyrus S. Beard, of VF-50 from the carrier Bataan, downed two Zeros over the Japanese fleet and damaged another as he fought to protect his flight of Avengers. He summed up the historic action:“Like 200 other guys I was a brand new ensign facing my first fleet action, combating the extreme in every way: heavy opposition, long range and no gas, bad weather, confusion, and a return at night for a carrier landing. Fortunately I made it back with only a few bullet holes, and my reactions were like every other pilot—scared as hell!”

For the Japanese navy, the First Battle of the Philippine Sea had been a virtual coup de grâce to its once dominant carrier aviation force. TF-58’s long-range strike had sunk Hiyo and damaged Zuikaku, Junyo and Chiyoda, two cruisers and the battleship Haruna. Two fleet oilers had also been sunk and one damaged. Of the carriers’ air complements, only 35 aircraft survived the battle from an original force of some 470. For the remainder of the war that once superb Japanese carrier air arm could only be used as a decoy. In the Second Battle of the Philippine Sea, the decisive October 1944 struggle off Leyte, the Japanese could muster just 116 carrier aircraft. Zuikaku, Chitose, Chiyoda and Zuiho would all be sent to the bottom.

But it was not Ozawa’s strategy in the epic June 19-20 air battles that had virtually eliminated Japan’s naval air arm as a force in the Pacific War, so much as the wishful assumptions on which it was based. The fatal wounds to Japan’s carrier aviation were largely self-inflicted. The Japanese fleet commanders made overly optimistic estimates based on pure conjecture: They assumed the land-based air units on Guam and Rota had somehow survived and were a viable offensive force; they imagined that their air attacks of June 19 had sunk up to four American aircraft carriers; and despite the lack of available fighters to defend the Combined Fleet, they did not distance themselves from TF-58 on June 20, but lurked in the Philippine Sea in hopes of a ship-to-ship engagement. Thus through the closing months of the war, the surviving land-based, largely inexperienced Japanese aviators were obliged to employ a terrifying new tactic: kamikaze assaults.

John W. “Jack” Lambert has written extensively about World War II air combat. Additional reading: Clash of the Carriers: The True Story of the Marianas Turkey Shoot of World War II, by Barrett Tillman.

Originally published in the November 2011 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.