CHARLES TOWN, VIRGINIA

DECEMBER 2, 1859

The day was slightly overcast, as one observer wrote, “with a gentle haze in the atmosphere that softened without obscuring the magnificent prospect afforded here.” The scaffold gave a stunning view of the Shenandoah Valley; it would be the last thing the old man would see.

“Old Brown,” they called him, and “Osawatomie Brown,” but his given name was John, after Christ’s favorite disciple. And now he was paying with his neck for the havoc he had wreaked in his little war on Harpers Ferry, three miles to the south.

The authorities had chosen a large field just southeast of town. Emotions were strong against the old man, and Governor Henry A. Wise had advised all citizens of Charles Town to remain at home. Only a small crowd of locals was allowed entry; all others were barred by fence and troops. The gallows stood in the center of the field, with row upon row of soldiers formed in a solid square around it. A combination of home guard and Regular Army, 1,500 in all, stood ranked in companies—each in its distinctively colored uniforms and bearing its own flag. There were men here whose names in a few short years would themselves be known to a nation at war: Robert E. Lee, now a lieutenant colonel of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry; Private John Yates Beall of the local Botts Greys, soon to achieve fame as a Confederate raider and to share Brown’s fate; and John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and a volunteer in the Virginia Greys, who couldn’t resist entertaining the troops with passages from Shakespeare.

Directly behind the gallows, in their red flannel shirts, were assembled a detachment of 80 cadets—boys, really—of the Virginia Military Institute. By order of their commandant, Colonel Francis H. Smith, they had slept in their uniforms and accouterments, with loaded weapons at their sides. Reveille had awakened them at 6 a.m., and they had stood on the field most of the morning. Though fatigued, they were deeply conscious of the honor and the responsibility that was theirs. Colonel Smith had made it clear that they were to “abstain from all thoughtless levity…and that they will remember that called into service as men they will acquit themselves like men.”

Twenty-one of the youths had been designated as artillery, and were positioned between a battery of two howitzers. The commander and instructor under whom they stood was Major Thomas Jonathan Jackson.

As a professor of science and mathematics, Jackson was, by all accounts, a dismal failure; intolerant and uncommunicative, it was once said of him, “If silence is golden, Jackson was a bonanza.” Unremarkable in his appearance—he was more than once described as “ordinary looking”—Jackson was a man of rigid bearing and Spartan habits, humorless and of fervent Calvinist convictions. He took neither tobacco nor spirits. He had peculiar habits; he was said to suck on lemons as a “rare treat,” and at times he walked about with his right arm raised. He believed this limb to be longer than the other, and had somehow come to the opinion that this practice improved his circulation.

He was compulsively secretive, and a rigid disciplinarian. His pale blue eyes burned at times with such intensity that they earned him the nickname “Old Blue Light.” And beyond the sum of his parts, he was surpassingly brilliant in the field. Jackson had proved himself a devil with cannon in the late war with Mexico, and soon would again. His command of artillery made all things possible.

And as he would prove on this execution day, he was also a strict observer and recorder of history. After John Brown had been hanged, his body cut down and the troops dismissed, Jackson wrote a letter to his wife, Mary Anna, describing the momentous event he had just witnessed. The letter falls under the heading of straightforward reportage, remarkable in its accuracy and attention to detail. And it also provides a rare glimpse into the thinking of this most private man.

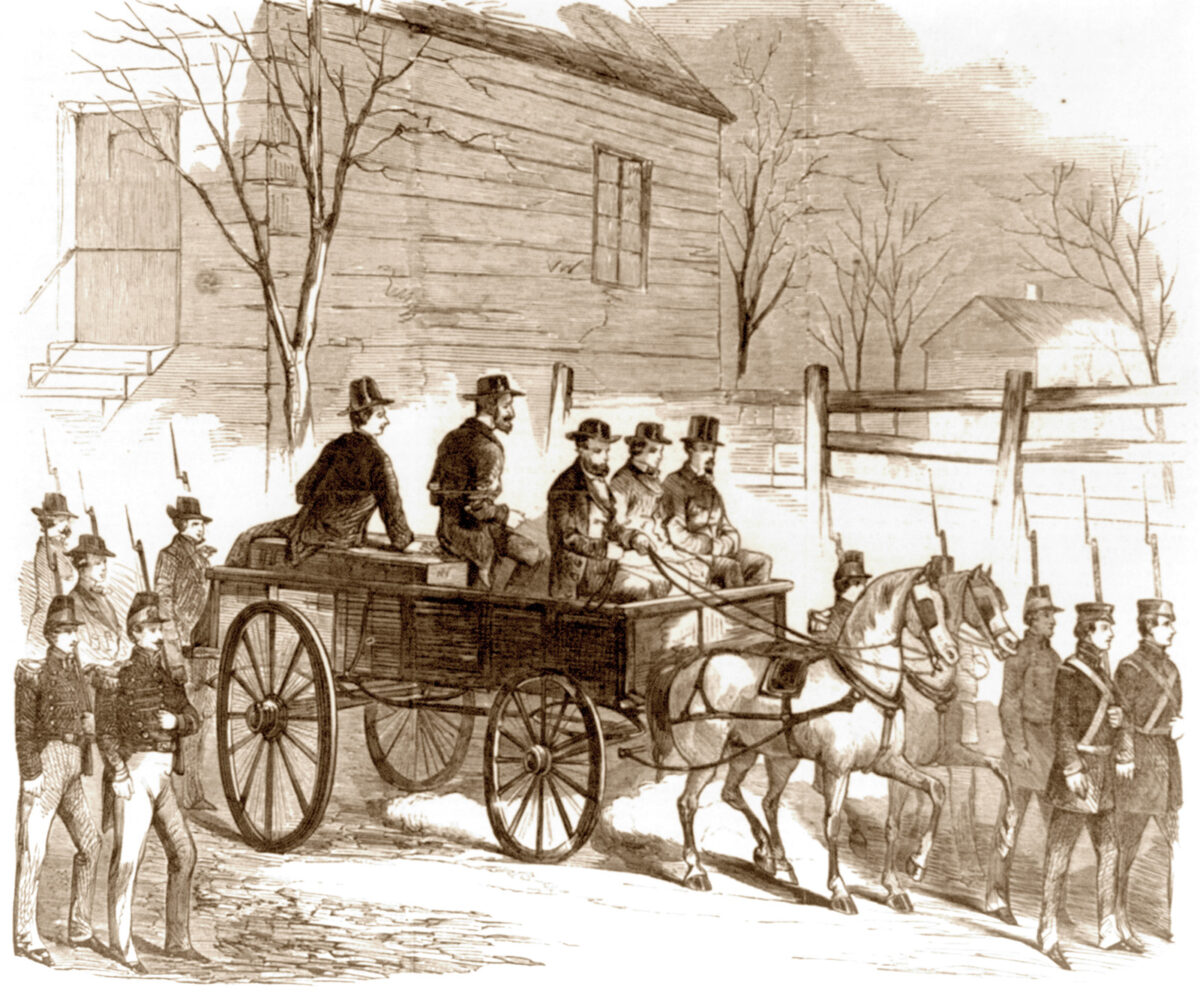

Jackson described Brown’s approach, seated on his own coffin in the wagon. “He was dressed in carpet slippers of predominating red, white socks, black pants, black frock coat, black vest and black slouch hat.” Brown, arms bound behind him, climbed the scaffold “with apparent cheerfulness,” and “shook hands with several who were standing around him.” The sheriff “placed the rope around his neck, then threw a white cap over his head.” It was so quiet that, when the officer asked Brown if he wanted to be informed when all was ready, Jackson heard the old man reply that “it made no difference, provided he was not kept waiting too long.”

But wait he did. With the troops standing rigidly at attention, the seconds passed painfully slowly as Brown stood patiently on the trap, face covered, for at least another 10 minutes while the escort companies joined the formation. Watching the condemned man calmly await his own destruction, Jackson contemplated the concept of mortality.

“I was much impressed with the thought that before me stood a man, in the full vigor of health, who must in a few minutes be in eternity. I sent up a petition that he might be saved. Awful was the thought that he might in a few minutes receive the sentence ‘Depart ye wicked into everlasting fire.’” Enemy though John Brown might be, Jackson wished only salvation for the man’s soul.

Then, Jackson wrote, the signal was given; “the rope was cut by a single blow, and Brown fell through about 25 inches….” The drop was not sufficient to break his neck, and his body, from the knees up, was visible to all as he suffered his death struggles. “His arms below the elbow,” Jackson observed, “flew up, hands clenched,” as he fought for breath. The only sound was the groaning of the hemp. Slowly, the body quieted, as “his arms gradually fell by spasmodic jerks.” Finally, John Brown hung limp at rope’s end, and all again was silence.

As Brown’s body swayed gently in the breeze, the devout Jackson questioned whether the old man had been ready to face death: “I hope that he was prepared to die, but I am very doubtful—he wouldn’t have a minister with him.”

Yet at the very beginning of his letter, Jackson betrayed a soldier’s respect for Brown’s bearing. “John Brown was hung today,” he wrote. “He behaved with unflinching firmness.” In his own stoic way, Jackson was acknowledging that John Brown had, in the parlance of the time, “made a good death.”

Less than four years later, after the Battle of Chancellorsville, Lt. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson—“Stonewall”—would again have the opportunity to consider the prospect of eternity.

Author and historian Ron Soodalter has been a teacher, flamenco guitarist, scrimshander (!), folklorist and curator. He is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader.

Originally published in the September 2009 issue of America’s Civil War.