Before the children of the world read about one fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish, Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, was honing his rhyming skills on a somewhat different audience — the U.S. Army.

As Americans turned citizen-soldier, the Army found themselves in a quandary — how could the service turn the youth of America into fierce, trained soldiers?

Part of the solution? Training films.

“Training films were used during World War I, but became even more popular during World War II. Career soldiers, however, found the films unhelpful, and young recruits found them boring,” according to the National Archives.

Enter Geisel, who, before the war, worked as a writer and illustrator. Under the direction of Frank Capra (“It’s A Wonderful Life”), Geisel offered up his services to the U.S. Army’s Information and Education Division.

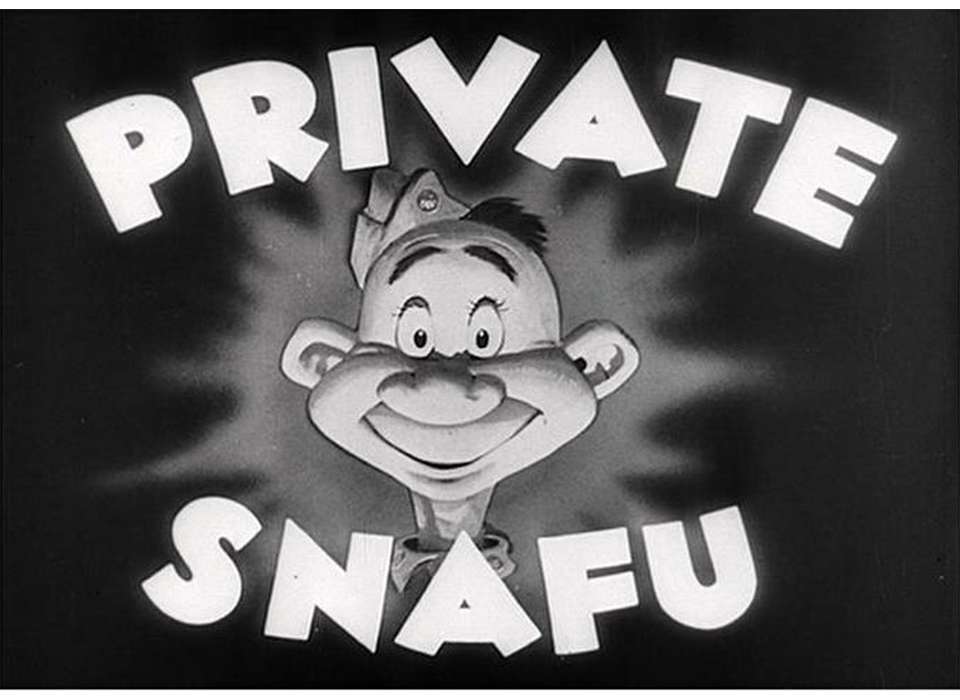

There, alongside other talented artists such as Mel Blanc (the voice of Bugs Bunny) and Chuck Jones (animator on the “Looney Tunes”), Geisel set to work to create the beloved character the trio dubbed Private Snafu.

Doing away with the basic, often cheesy films of 1917-18, the Private Snafu cartoon took on the war with slapstick, often raunchy humor.

Per the National Archives, the Army-Navy Screen Magazine (ANSM) was a biweekly production that featured a variety of short segments including propaganda, entertainment and training films.

Snafu, an acronym for Situation Normal: All Fouled (or F–ked) Up, was the Army’s attempt to relate to the non-career soldier. And by 1943 standards, scantily clad women (albeit in cartoon form), profanity and sexual innuendos were deemed just the ticket.

From Snafu’s premiere in 1943 until the end of its run in 1946, 28 cartoons tackled myriad problems these young soldiers might face — from breaches of security and malaria to spreading rumors and letting loose lips sink ships in order to impress members of the opposite sex.

And while Geisel made most of his war contributions from the safety of “Fort Fox” in California, he did briefly experience life on the front lines.

In November 1944, Geisel was sent to Europe to screen “Your Job in Germany” to top American generals in the Western Theater. Although six months before the German capitulation, the film short was, according to the Archives, “an orientation film for United States Army personnel who would occupy Germany after the war was over.”

Geisel later recalled that he managed to play it for every high-ranking general in the theater except for one: Gen. George Patton.

“Somebody else took the film and played it for Patton,” Geisel told his biographers, Judith and Neil Morgan. “I was told he said ‘Bullshit!’ and walked out of the room.”

The film advised Army personnel to avoid fraternization with the Germans post-war, with Geisel writing in his script:

“They cannot come back into the civilized fold just by sticking out their hand and saying ‘sorry’. Sorry? Not sorry they caused the war; they’re only sorry they lost it. That is the hand that heiled Hitler; that is the hand that dropped the bombs on defenseless Rotterdam, Brussels, Belgrade. Don’t clasp that hand. It’s not the kind of a hand you can clasp in friendship.”

It was during this time, while traveling around the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France and Belgium, that Geisel found himself trapped 10 miles behind enemy lines on Dec. 16, 1944, during Germany’s last counteroffensive in Bastogne.

Geisel reportedly wanted to go to the front to “see what was what,” according to Capt. Wentworth Eldredge’s account.

Maj. “Ralph [Ingersoll] and I talked it over,” Eldredge wrote, “and concluded that the ‘safest’ place would be the 106th Division front — a very calm sector. There won’t be much action because we’ve just done an intelligence sweep of the area.”

Exactly what occurred next remains somewhat of a mystery, Rick Beyer wrote in the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine.

“Geisel’s crisply typed ‘Overseas Itinerary,’ submitted upon his return, offers little information,” Beyer wrote. “It baldly states that he drove from Luxembourg to Aachen, Germany, on December 16; from Aachen to Verviers, Belgium, on December 17; and from Verviers to the safety of Brussels on December 18.”

It would take three days before the British could break through and rescue Geisel and his military police escort.

“Nobody came along and put up a sign saying, ‘This is the Battle of the Bulge,’” Geisel later told a New Yorker reporter. “How was I supposed to know? I thought the fact that we didn’t seem to be able to find any friendly troops in any direction was just one of the normal occurrences of combat.”

In typical Dr. Seussian flare, Geisel added, “The retreat we beat, was accomplished with a speed that will never be beaten.”

Geisel was honorably discharged by war’s end, having attained the rank of lieutenant colonel. But it wouldn’t be his last foray with the military.

Geisel’s “Your Job in Germany” was later expanded into a 1945 American short documentary film, winning an Oscar the following year for Documentary Short Subject.

The following year, according to the Archives, Geisel adapted his short companion piece, “Our Job in Japan,” which was largely suppressed by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, into a feature-length documentary — “Design for Death” — that won the 1947 Academy Award.

Talk about the places you’ll go. A real Uncle Sam-I-am.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.