During the Great Age of Sail in the late 1800s, America’s West Coast ports were notorious for their double-dealing crimps and captains who preyed upon the unsuspecting and unwary to fill their almost never-ending need for sailors to man their ships.

It was, no doubt, cold and drizzly that October night in 1892 when about two dozen men broke into a cellar beneath the Snug Harbor Saloon in Portland, Oregon. By flickering candlelight, they saw a room full of wooden kegs and assumed that they contained some of the saloon’s whiskey. Perhaps they found a glass to drink out of, or maybe they used their hands, but the kegged liquid they drank soon had many of the group vomiting and collapsing in pain, more dead than drunk, on the cold cellar floor. The cellar did not belong to the Snug Harbor, as they had assumed, but rather to Johnson and Sons Undertakers: The men had just swilled copious quantities of stored formaldehyde.

That same night, Joseph “Bunco” Kelly, one of Portland’s most infamous shanghaiers, or crimps, was walking the streets looking for 20 men willing, desperate or gullible enough to sign up as crew on the ship Flying Prince. As he went past the Snug Harbor and peered down through the open cellar doors, Kelly must have smiled to himself: His search was over. True, the men had just poisoned themselves, but that detail did not deter Kelly. With the help of some of his goons, Kelly quickly transferred the men to the waiting ship, telling the captain a story of a barroom binge, and reportedly received $50 a head. Ironically, it was later claimed that as they carried the men aboard, the captain swore he had “never seen so many dead drunks in his life.”

More than half of the pickled men succumbed to the formaldehyde. The next day, when their bodies were offloaded onto the downtown wharf, the story of Bunco Kelly’s trick quickly spread, adding to the reputation both of the man and the young port town as corrupt and dangerous. All the major seaports of the Pacific Coast—San Francisco; Portland; Seattle and Port Townsend, Wash.; and Vancouver, British Columbia—were involved in this quasi-slave trade at the end of the 19th century, but Portland and San Francisco were the worst. It is estimated that in the second half of the 1800s nearly 100,000 men were drugged or otherwise tricked into working on ships from these two ports alone. Bunco Kelly and his peers were busy men.

Sailors have never had it easy. From the days of slave labor–propelled Greek and Roman galleys to the late 1800s, the task of finding large numbers of men willing to perform hard and dangerous physical labor for little money resulted in atrocities and abuse. The labor needs of a sail-powered vessel were immense, requiring not just skilled hands but dozens of men to simply pull on a rope when so ordered. While sailors with specialized skills may have had some ability to choose their ship, the unskilled did not. And in a port town, any reasonably healthy man was eyed by the crimps as a potential sailor.

The 19th century, the heyday of sail-powered merchant shipping, was also the heyday of the sea pimp, or crimp, who supplied unscrupulous captains with fresh crew members, often unwilling ones. In other words, the men were shanghaied. (The term crimp, originally British slang for “agent,” probably arrived in America with British sailors. The term “shanghai” likely arose because many crimped sailors ended up in Shanghai, China, a major port in the days of sail.)

Crimping took place in major ports around the world: London, New York and Hong Kong were all infamously dangerous places to be a sailor. Herman Melville, in his autobiographical novel Redburn, described the threats to a sailor in Liverpool based on an 1837 visit to that port, when he worked as a ship’s boy on a passenger boat:

Besides, of all seaports in the world, Liverpool, perhaps, most abounds in all the variety of land-sharks, land-rats, and other vermin, which make the hapless mariner their prey. In the shape of landlords, barkeepers, clothiers, crimps, and boarding-house loungers, the landsharks devour him, limb by limb; while the land-rats and mice constantly nibble at his purse.

Sailors looking for cheap housing, cheap booze and cheap sex were easy targets for ruthless individuals with few morals and many connections in the bars and boardinghouses that sailors frequented. In fact, many of the most successful crimps owned boardinghouses, giving them a ready supply of potential clients. Crimps usually received from $25 to $50 per sailor, which was an advance on the sailor’s eventual pay, subtracted from what the crew member was to receive, in much the same way that modern temporary agencies subtract a percentage from the paychecks of people they place.

The nature of shipping at the time made crimping practical. Sailors signed long-term, often multiyear contracts with a ship. They were fed and housed during voyages, but paid at the end of the contract term. In the idle periods between voyages, a ship full of hungry sailors was expensive to maintain, so captains and owners often tried to make life aboard the moored ship intolerable, hoping that their sailors would quit early, void their contracts and become ineligible for pay. When the ship was later loaded with cargo, captains would hire a crimp to gather replacement crew members at short notice. The least scrupulous captains would even give their sailors shore leave and arrange to have them shanghaied onto another vessel, so the captain could pocket the sailors’ pay.

Journalist Broughton Brandenburg wrote about his narrow escape from a crimp in a 1903 edition of Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. He described being befriended in a saloon by a “crafty-faced middle aged Scotchwoman” who told him that her brother could get Brandenburg a position on a “gentleman’s yacht.” He was taken to a boardinghouse and held there for two days before a man arrived with a tale of a ship going “a short distance” that needed a crew. This man provided free liquor to all the boarders before delivering them to a “rotten old guano tramp.” Brandenburg, who had feigned inebriation, discovered that the ship was headed for Australia and stepped back onto the dock, picking up an iron rod for self-defense. The boardinghouse master threatened him, but eventually accepted a small fee and allowed Brandenburg to flee. The journalist went on to detail the dangers facing sailors around the world:

The process is everywhere the same. Sailors with money fall into the hands of women who rob them and turn them over to the crimps, or runners, who persuade the men to leave the ships they are on for better jobs that never materialize, and then land them in the crimp’s clutches, and once they are inside one of these boarding-houses they must stay there, if they would have food or shelter at all, and when the boarding-house keeper finds a ship on which sober men will not sign he drugs his victims and puts them aboard or forces them to go, and reaps his harvest by having got all the money the man had from his last ship and drawing from a month or two months advance on the new one.

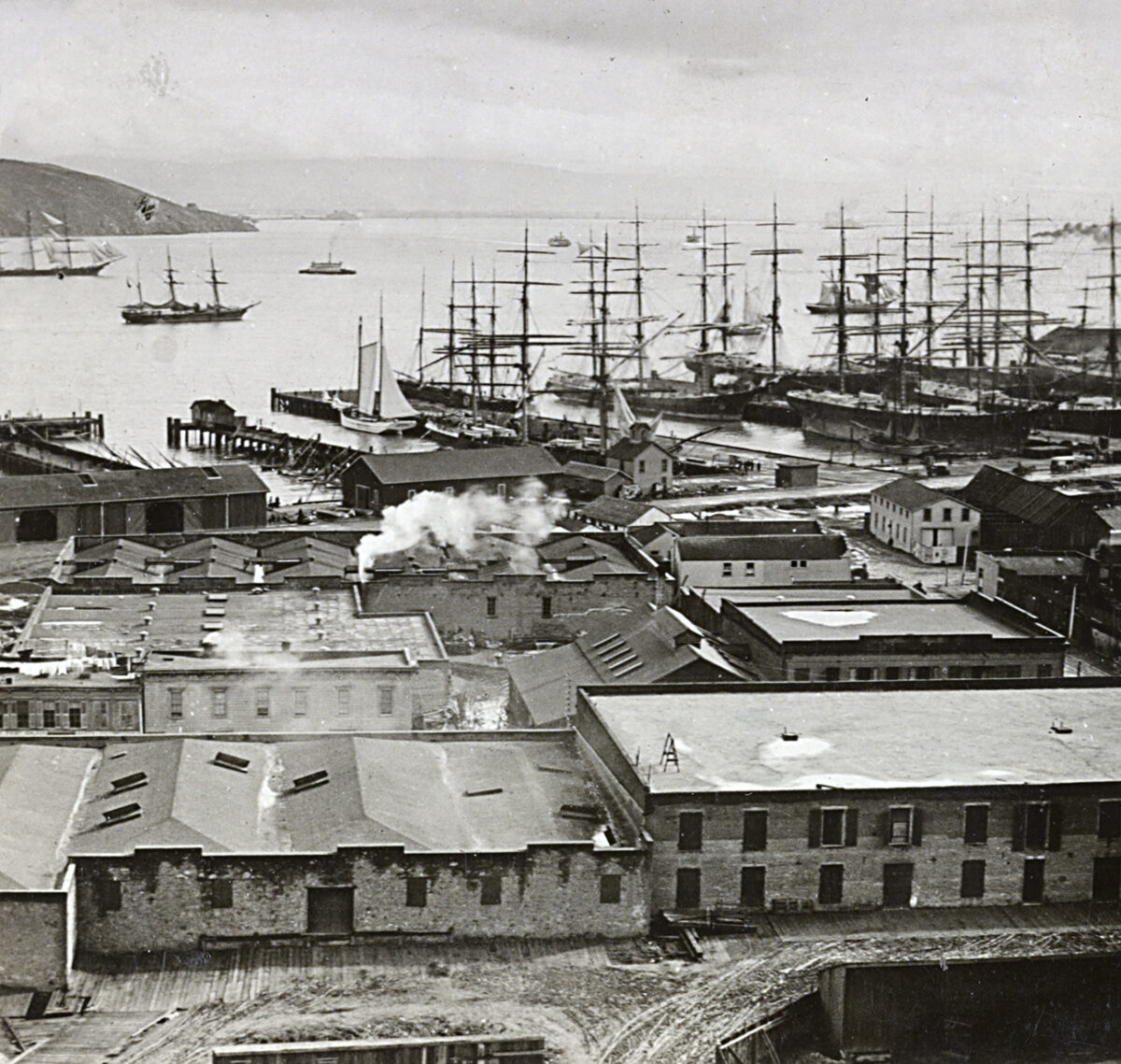

Toward the end of the sailing ship’s reign in the last quarter of the 19th century, the West Coast of the United States was reported to have the most dangerous ports in the world. Portland was a rough, corrupt city whose economy had risen quickly through timber and grain shipping. In the 1890s it was common for 100 windjammers to be docked in Portland Harbor, a slight bend in the Willamette River just a few miles south of the Columbia River. It was an area of the country still considered untamed. (Lewis and Clark had arrived less than 100 years before, and the town had only been founded in 1845.) The town’s frontier feeling and apparent wealth attracted the very men who were easy to shanghai: young, unemployed risk-takers with few connections to family or allegiances to jobs.

Arriving in Portland, these young men often stayed in boardinghouses owned by one of Bunco Kelly’s competitors, the nattily dressed James Turk, whose violent demeanor was even noted in a Portland Chamber of Commerce report: “The inhumanity and cruelty of Turk towards seamen has never been denied by men who knew him.” Turk is widely believed to have introduced crimping to Portland, but more infamously, is also widely believed to have crimped his own son as a disciplinary measure for rampant womanizing and heavy drinking.

In a series of articles written by reporter Stewart Holbrook for the Oregonian newspaper in the early 1930s, Portland residents who had experienced shanghaiing talked about Turk. One interviewee, A.E. Clarke, told Holbrook about an incident in October 1891. Clarke was wandering down Burnside Street when he met a man who invited him aboard to a riverboat party. Clarke accepted the offer and spent the afternoon drinking and chatting with young women as the boat made its way to Astoria, a port town located where the Columbia River enters the Pacific Ocean. Once there, Clarke was told to sign a passenger list so the crew would know when everyone was back on board, and then he was taken on a “tour” of an iron-hulled, deep-sea square-rigger called T.F. Oakes. At that point, Clarke and the other victims were held at gunpoint, manacled and shoved in a dark hold. It was seven years before Clarke saw Portland again.

As part of his ordeal, Clarke described malnutrition, beatings and an insane captain who executed crew members at random. He also described the first mate, Black Johnson, as tyrannical, and recalled the night at sea when, by prearranged signal, the crew members let go of a sail’s line, sending Johnson overboard. Johnson clung to the rope, screaming, until someone pounded his fingers with an iron bar to make him let go.

The fact that, daily, dozens of men, even in a frontier town, could secretly be drugged and smuggled aboard ships was due in part to a series of interconnected tunnels crisscrossing beneath Portland’s waterfront—an area that once was full of bars and boardinghouses. The exact origins of the tunnels are not known, but the system probably developed slowly as walls between basements and cellars were broken through and underground excavations connected others. One of the tunnels led 23 blocks inland.

The tunnels, which apparently housed various nefarious operations, including opium dens and whorehouses, also were used for some legitimate businesses, such as the underground restaurant advertising “Glass of Buttermilk and 2 Donuts or Snail for 5 cents.” At least one of the tunnels has been described as wide enough to carry a wagon. According to eyewitnesses interviewed by Holbrook, trapdoors in bars allowed crimps and their employees to drop drugged or drunk victims into a tunnel, where they would be held in small caged rooms until a ship was ready.

Turk, Kelly and their competitors were said to have worked these tunnels industriously. The reputed star of one of Kelly’s most famous crimping scams still stands in one of them today. Unable to find one final sailor to round out a crew order, Kelly noticed a cedar wood dime store Indian standing outside a closed shop. Wrapping it up in multiple blankets so that only the statue’s dark face could be seen in the shadows, Kelly delivered the stiff package to the captain with the rest of his living crew, charging him extra for the “drunk” sailor because of the reputation American Indians had for strength.

As the story goes, the captain hurled the wooden Indian overboard when he discovered the rip-off; it was recovered and eventually sent back to Portland. True or not, this story gave Bunco Kelly his nickname, for his ability to spin “bunkum” into cash.

Successful crimps like Kelly and Turk gained a tremendous amount of power through their wealth, which helped them avoid legal entanglements. Another crimp and boardinghouse owner, Larry Sullivan, liked to boast that he was “King of the City,” and once aimed a loaded shotgun at police trying to arrest him for running a crooked polling station in his boardinghouse. No serious charges were ever laid against him, although it was later discovered that he had paid a Dutch crew to vote for the politician of his choice.

Portland wasn’t alone. In the early years of the gold rush, when most fit men were seeking their fortunes in the mountains, the value of potential sailors actually increased, and a crimp could receive as much as $300 per sailor, the equivalent of about $5,000 today. Following the rush for gold in the mid-1800s, men unable to strike it rich, but ready and often desperate for work, filled San Francisco.

San Francisco had its own well-known crimps, such as Shanghai Kelly and his employee, Johnny Devine. San Francisco was also known for two female crimps, Miss Piggott and Mother Bronson, bar owners and tenders famed for their tempers. Mother Bronson boasted that she could knock out an ox with a single punch and, apparently, nobody ever challenged her to prove it. Both women reportedly utilized cocktails doctored with opium or laudanum and trapdoors to capture involuntary sailors.

Miss Piggott employed a runner from Lapland named Nikko. In several accounts, Nikko was described as a skilled builder of dummies that he would pass off to captains as, of course, drunken sailors. Nikko’s finishing touch involved sewing a rat into the sleeves of the “sailor’s” coat, so that the dummy twitched in a lifelike manner on deck.

Shanghai Kelly, on the other hand, unlike many of his San Francisco competitors, did not use dummies or statues to improve his sales. He was a short, stocky Irishman with red hair and a red beard, universally feared. Kelly’s saloon sat close enough to the waterfront that he could dock a boat underneath his bar, allowing his victims, drugged and dropped through a trapdoor, to land in a small vessel ready to lighter them out to a waiting ship. It was said that Kelly, along with doctoring some men’s drinks, also sometimes handed out cigars laced with opium, which he called the “Shanghai smoke.”

One of Shanghai Kelly’s best-known crimping successes, however, did not center on his bar or boardinghouse. Needing a large number of sailors for three ships anchored outside the Golden Gate, Kelly hired the paddle-wheeled steamship Goliah and announced that he would be throwing a birthday party for himself onboard. Everybody was welcome, and the booze was free. Naturally, Goliah filled up quickly and was carrying more than 90 men when it steamed away from the dock and across San Francisco Bay toward the open ocean. Kelly, of course, had drugged the liquor and beer, so within two hours, when Goliah pulled up alongside the first of the three ships, all of the revelers were passed out. They had to be hauled aboard in nets, like cargo.

Johnny Devine, a thug known locally as the “Shanghai Chicken,” was a tough New Yorker who arrived in San Francisco in 1861, claiming to have been crimped out of New York two years earlier. He intended to make a name for himself as a boxer, but, after being knocked unconscious in an early bout, he turned to petty crimes and hijackings. He was known for being fearless and vicious, and once stole a drunken sailor out of the arms of another runner, shooting the runner twice when he protested.

In nine months, Devine was arrested 27 times for as many different crimes, but the only punishment he received during that period was 50 days in jail. He was once hired for $50 to attack a man, and did his work so well that his victim was hospitalized for several months. In 1868 Devine and Johnny Nyland, another of Shanghai Kelly’s runners, shot and stabbed half a dozen men in a tavern fight before Devine’s knife was stripped from him. When Devine raised his pistol, his opponent slashed him with the knife, cutting off Devine’s left hand. Devine replaced the hand with a hook, sharpened to a fine point, that made him even fiercer in battle. Eventually Devine started drinking so heavily that Kelly was forced to fire him and then tried to shanghai him. Devine escaped and spent the next few years eking out a living as a thief and burglar before murdering a German sailor and receiving the death sentence. He was hanged in San Francisco in 1873.

Most of our knowledge of crimping comes from oral histories collected in the early 20th century. But a shipping master who served as a go-between for captains and crimps in San Francisco, James Laflin, kept a log (now in the San Francisco Maritime Museum) listing all crimps with whom he did business, the number of men shanghaied and the amount he paid for each. It gives an idea of how widespread the abuses were to sailors’ rights. In 1890 alone, Laflin paid out more than $71,000 in advances for 1,168 crimped sailors, an average of about $61 a head. A third of the advances went to clothiers, the rest to saloonkeepers and boardinghouse owners. All in all, more than 400 individuals or businesses received advances on the sailors’ pay.

Although powerful and wealthy individuals successfully kept politicians and attorneys away from their crimping operations for years, their control of the trade was eventually challenged. The first progressive action came from the sailors themselves, who, in 1866, formed the West Coast’s first seaman’s union. Organized in San Francisco, the Seamen’s Friendly Union and Protective Society didn’t last, but it set the stage for what would eventually become the Coast Seamen’s Union (CSU) in 1885, the world’s first permanent sailors’ union. The CSU’s meager power gradually spread as sailors in coastal vessels plying the West Coast slowly infiltrated more long-term and deep-water vessels. The CSU was followed in 1892 by the International Seamen’s Union (ISU), which covered the entire U.S. coastline and the Great Lakes.

As the strength of the unions grew (along with public outrage following books such as Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast, published in 1841), local and federal governments started to act. In 1882, for example, Jesse Millais, the second mate of the clipper ship Davy Crockett, was arrested in New York after a 60-year-old crewman named Andreas Stork complained that he had been taken aboard the vessel against his will in San Francisco. In the courtroom, Stork told a story about regular beatings, brandings with a hot iron and, on one occasion, being held over the ship’s side and threatened with death if he spoke about the abuses. What is notable, though, is that ultimately Millais was held responsible for his abuse of Stork, not for forcing him aboard.

This was not unusual. The legal defense of sailors had for centuries been weak, especially when it came to their rights to choose their place of employment. In fact, in 1897, the U.S. Supreme Court heard a case that attempted to apply the 13th Amendment (outlawing slavery and involuntary servitude) to four sailing ship crew members who had attempted to leave Arago at the port of Astoria, Ore., only to be arrested and forced back aboard when the ship departed. The decision to reject the application of the 13th Amendment in this case lay in the idea that, by precedent, sailors have always been treated poorly. Justice Henry Brown, writing for the majority, proclaimed, “Seamen…are deficient in that full and intelligent responsibility for their acts that is accredited to ordinary adults.” Brown’s opinion continued:

We know of no better answer to make than to say that services which have from time immemorial been treated as exceptional shall not be regarded as within [the Court’s] purview. From the earliest historical period the contract of the sailor has been treated as an exceptional one, and involving, to a certain extent, the surrender of his personal liberty during the life of the contract.

Despite this ingrained attitude, Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette, supported by the ISU and spurred in part by the sinking of Titanic in 1912, introduced the La Follette Seamen’s Act into Congress. The Seamen’s Act regulated sailors’ wages, food, safety and living conditions on large ships. President Woodrow Wilson signed it in 1915, finally giving sailors the legal footing to expect a higher standard of treatment than had been available to them for centuries.

In addition to the growing strength of sailor unions and their legal status, crimping eventually died out simply because it was no longer profitable. By the early 20th century, ocean-going steamships regularly plied the world’s waterways, requiring fewer crew members and carrying more cargo in less time than sailing ships. Since a single mechanic could replace dozens of unskilled men and the union protected sailors from abuse, crimping came to an end. Today, fortunately, only the stories remain.

Originally published in the June 2006 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.