Edited by Nancy Tappan

It is one of the most celebrated letters in American history. First heard on a wide scale during Ken Burns’ The Civil War documentary on September 23, 1990, a letter presented as the final missive by Major Sullivan Ballou of the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry has over the years been read repeatedly and published in many accounts as the finest expression of why Northern soldiers went to war to preserve the Union.

Since 1990, however, some in the Civil War community have debated whether the 32-year-old major did indeed write that letter to his wife, Sarah. We will likely never get a definitive answer in this debate, as an original version of the letter in Ballou’s handwriting has yet to be found.

In her 2006 biography of Ballou, For Love and Liberty, Robin Young dismisses such “conspiracy buffs” while declaring the letter a masterpiece—“no doubt the handiwork of a master of the art of rhetoric.” She analyzed other letters that Ballou is confirmed to have written and argued in her book that the Rhode Island lawyer and politician, who studied and taught oratory in his youth, was indisputably the author of the renowned document. But when given an opportunity to compare the famous letter and the authenticated ones, other experts see significant thematic and tonal differences among them. They argue that in the other dispatches—sent about the same time in July 1861, as Ballou awaited his first taste of battle—the major clearly was concerned with more down-to-earth matters and never composed in the lofty, ethereal tones of the famed letter. (For the viewpoint of two of those experts, see Cushman and Samuels.)

The following article will explore the provenance of the letter and shed light on some of the questions surrounding it.

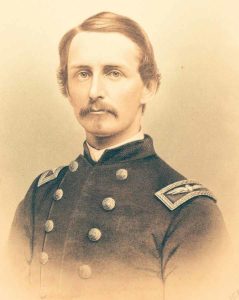

Sullivan Ballou was born March 28, 1829, in Smithfield, R.I. Although he grew up in poverty, he would attend Brown University and become known as an orator.

In 1850, Ballou moved to Ballston, N.Y., to teach oratory at the National Law School, where he also studied law. Admitted to the Rhode Island Bar in 1853, he set up a practice in his native state. Ballou married Sarah Hart Shumway on October 15, 1855, and they had two sons, Edgar and William. He became clerk of the Rhode Island House of Representatives, and in 1857 became a state representative, serving one year as speaker. Known as a Radical Republican, he supported Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Ballou was REMEMBERED as a man whose heart was entirely in the northern cause[/quote]

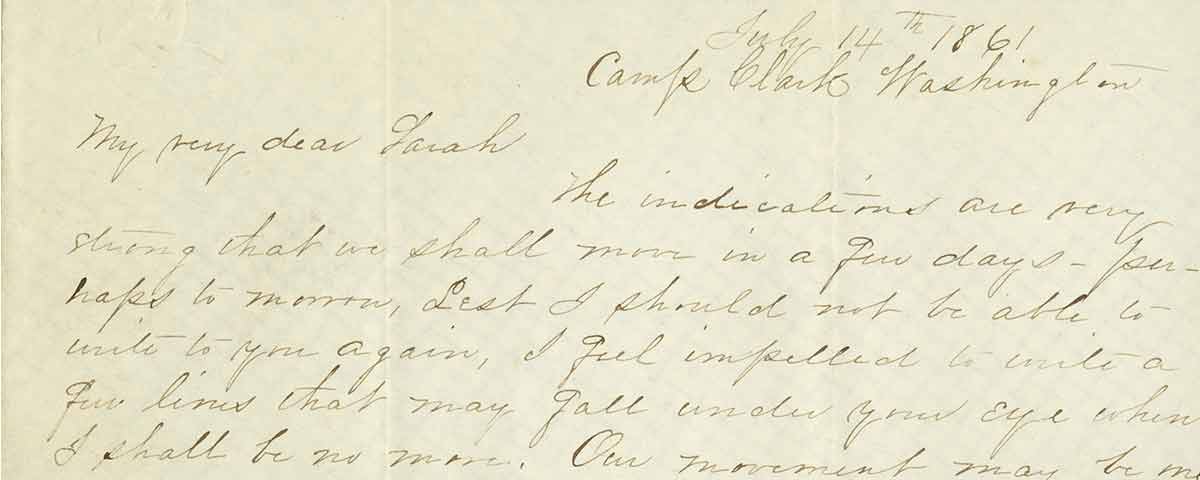

In June 1861, just two months into the Civil War, Ballou was commissioned major of the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry and accompanied the regiment to Washington, D.C. He wrote Sarah repeatedly from his encampment. The Ballou Papers at the Rhode Island Historical Society contain two letters to Sarah dated July 14, 1861, a few days before the regiment marched off to battle in Virginia. One letter, confirmed to be in Ballou’s handwriting, is brisk and reassuring and addresses issues related to his personal affairs. The other, in someone else’s handwriting, is reflective and sentimental, and sets out the thoughts of a man who believes he might well be killed in battle. It is that second letter that is now part of the American canon.

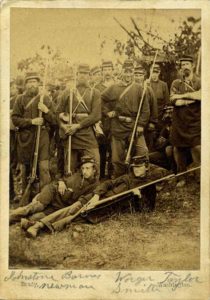

On July 21, 1861, the 2nd Rhode Island led the Union advance at First Bull Run. Charging up the winding slopes of Matthews Hill, the Rhode Islanders suffered heavy casualties, fighting unsupported for nearly 45 minutes before reinforcements arrived. During the fighting, Ballou’s horse was killed by a cannonball that also tore off part of the major’s right leg. Taken first to a Confederate field hospital, he died on July 28 or 29 and was buried in the nearby Sudley Churchyard, near the 2nd Rhode Island’s Colonel John Slocum, who was also killed in the fighting. (For what happened to Ballou’s and Slocum’s bodies after burial, see “Sullivan Ballou’s Macabre Fate.”)

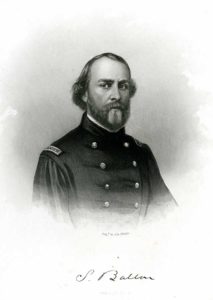

As noted earlier, no version of the famous letter in Ballou’s handwriting has been found, though a number of copies exist in various scripts. The letter first appeared in print in 1868 in a chapter written by Horatio Rogers Jr. in Brown University in the Civil War, a volume looking at Brown alumni killed in the war. Rogers, a Brown alumnus who also served in the 2nd Rhode Island, was a friend of Ballou’s. His sketch of his comrade’s life says the letter was found in Ballou’s trunk, left behind at Camp Clark when the regiment marched off to its first engagement at Manassas. Rogers, who led the 2nd Rhode Island at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg as a colonel, wrote briefly that the trunk, with the letter inside, was returned to Sarah Ballou in August 1861.

Rogers was a respected lawyer, eventually serving as Rhode Island’s attorney general and as an associate justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court. His sketch of Ballou’s life was typical of biographies published in the 19th century, painting the major as a family man, a talented attorney, and one whose heart was entirely in the Northern cause.

He quotes several of Ballou’s Camp Clark letters, and ends his chapter by reproducing the famous July 14 letter, which Rogers calls “his own best eulogy.” It is evident Rogers had access to some of Ballou’s other missives and interviewed family members, while recounting common experiences.

Stories have circulated that Rhode Island Governor William Sprague retrieved the trunk and returned it to Sarah. Rogers’ sketch makes no mention of that. Sprague did write Sarah a letter of condolence in October but refers in no way to the now-famous letter. In 1861, an early volume of the first Union martyrs of the Civil War, The Fallen Brave by John Gilmary Shea, included a brief sketch of Ballou’s life but does not mention the letter either. In 1867, Shea’s article about Ballou, together with an engraving of him in uniform, was included in John Russell Bartlett’s Memoirs of Rhode Island Officers. In his official 1875 history of the 2nd Rhode Island, Augustus Woodbury gives only a brief sketch of Ballou’s life and service, again with no reference to the letter.

The letter next appeared in print in 1888 in An Elaborate History and Genealogy of the Ballous in America by Adin Ballou, a distant relative—published in the same form as had appeared in the Brown University book. “That widow and those sons,” Adin Ballou wrote, “still survive—ever cherishing the following loving farewell.” He provided no further details on the origins or location of the letter, however.

It Wasn’t Ballou

» Stephen Cushman, the Robert C. Taylor Professor of English at the University of Virginia, is affiliated with the school’s Nau Center for Civil War History and has written extensively about the Civil War.

I am one of the thousands who found the Sullivan Ballou segment among the most powerful, moving, and memorable moments in Ken Burns’ documentary The Civil War. Moreover, I am not inclined to want to debunk or demystify such a moment. True, I have been trained as a professional skeptic, but I had no preexisting desire to puncture the Ballou balloon. If I had my way, it would continue to float in a blue sky above us. Nevertheless, I have no compunction saying there is no way the famed letter was penned by the same person who wrote the confirmed Ballou letters at the Rhode Island Historical Society that I’ve had a chance to read. If Sullivan were my student and had submitted these letters, I would suspect the famous one to be plagiarized.

For one, the tonal and linguistic discrepancies among the letters are significant. Any of us has many tones and linguistic modes at our command, but the differences among the Ballou letters do not suggest mere variations in a person’s verbal costuming—they suggest wholly different sensibilities and outlooks. Consider, for instance, that the famous letter mentions or addresses God five times, whereas the others mention—and never directly address—God only three times: twice in the July 10 letter, once in the second July 14 letter. Also, compare the use of Jesus’ Gethsemane prayer (“Not my will, but thine O God, be done”) in the famous July 14 letter with the utterly formulaic and conventional “God Bless you” closing of the other one penned that day.

Furthermore, not only are we supposed to believe Ballou wrote his wife twice the same day—it happens; George B. McClellan did so, for instance—but he wrote her once speaking about God in conventional, matter-of-fact terms and once addressing God as Jesus did before the Crucifixion. The famous letter also speaks of capitalized Omnipotence and Divine Providence, in addition to Civilization, Death, and Country; the writer of the other ones does not incline toward such capitalized abstractions, and when he does capitalize, he does so erratically and idiosyncratically (e.g., “Havelock” and “Rubber boots” following three lowercase uses of “rubber.”) Divine Providence versus rubber boots? These were not the same minds at work.

Whoever wrote the famous letter also was familiar with Shakespeare: “A pure love of my country and of the principles have often advocated before the people and ‘the name of honor that I love more than I fear death’ have called upon me, and I have obeyed.” That passage comes, slightly altered, from Julius Caesar, Act 1, Scene 2, where Brutus says to Cassius, “For let the gods so speed me as I love / The name of honor more than I fear death.” By contrast, the other Ballou letters exhibit no such literariness, and are much rougher stylistically and grammatically. They in fact have distinct problems with grammar and punctuation; the other is elegant and fairly clean.

The famous letter is elevated too in diction, from “Lest” in the second sentence to “thither” in the last. Neither of these archaic niceties appears in any of the others, which also lack one of the most poetic touches of the famous letter, the use of so-called genitive-link metaphors, such as “bitter fruit of orphanage” and “banner of my purpose.” These metaphors, built around “of” and originating in English translations of the Bible, show a level of figurative thinking and expression noticeably absent from the lesser known letters.

A conspicuous instance of visionary, nonliteral imagination comes at the end when the writer moves from anticipating his death to speaking from beyond the grave: “O Sarah, I wait for you there! Come to me, and lead thither my children.” The writer of the other letters seems wholly incapable of such a post-death thought experiment, and sounds unlike anyone who could muster the overwrought, 19th-century breathlessness building up to it.

As time went on, Sullivan Ballou’s letter was largely forgotten, but manuscript copies did circulate. Young writes in her 2006 biography that she found eight manuscript copies in repositories around the country. One of the two copies in the Rhode Island Historical Society archives may have been the one Sarah Ballou was aware of, as it was included in a collection she saved of her husband’s papers. The other was donated to the Rhode Island Historical Society in 1957 by Colonel Slocum’s descendants. A manuscript reproduction of the letter is at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Ill., formerly the Illinois State Historical Library.

Another copy wound up at the Chicago Historical Society in 1920, after a line of the Ballou family emigrated from New England to Illinois. The manuscript, donated by Charles J. Barnes, appears to have been copied directly from Brown University in the Civil War.

An excerpt of the Chicago letter was briefly quoted by Bruce Catton in his 1961 book The Coming Fury, though Catton mistakenly called Ballou “Major Sullivan Bullen” and stated he was from Illinois, rather than Rhode Island.

In 1976, Civil War historian Edward Longacre discovered the Chicago Ballou letter. He transcribed it and wrote a brief accompanying article about Ballou’s life. Longacre submitted the article to both Yankee Magazine and The Old Farmer’s Almanac, but it was never published.

The July 14 letter was brought to Ken Burns’ attention by Pulitzer Prize–winning author Don E. Fehrenbacher of Stanford University. In gathering material for Burns’ project, Fehrenbacher encountered the copy of it at the Lincoln Presidential Library and sent excerpts to Burns’ brother, Ric, in the summer of 1986. These excerpts, comprising only about half of the letter, were included in the documentary.

The excerpts, read by Paul Roebling and set to Jay Ungar’s haunting “Ashokan Farewell,” became for many the series’ most powerful moment. After Roebling reads them, narrator David McCullough states simply: “Major Sullivan Ballou was killed a week later at the First Battle of Bull Run.”

Sarah undoubtedly knew of the letter at some point, as the closing line, “I wait for you there. Come to me and lead thither my children,” is inscribed upon the Ballou memorial in Providence’s Swan Point Cemetery. According to Young, Ballou was interred in the plot in 1867; when exactly the large obelisk was put up is unknown. Rogers’ sketch was published in 1868.

After the broadcast, Ken Burns said, “It’s a letter that transcends even the extraordinary story of the Civil War. It’s about the tension and the love that exists between a man and a woman. Every man in this country wishes he could say those things to a woman.”

Immediately after the series premiered, phones rang “off the hook,” at PBS stations around the nation. People wanted to know more about Sullivan Ballou, and where his letter was located. Transcriptions were freely circulated, but no one was able to track down the original.

An unsupported theory that gained traction is that it was buried with Sarah Ballou when she died in 1917. In 2011, on the sesquicentennial anniversary of First Bull Run, when the letter was frequently quoted in newspapers, Ken Burns said that he is among those who believe the letter was buried with the widow. Neither Burns nor a studio representative could be reached for comment for this article.

Much attention has been focused on the differences between the famous letter and the other one definitely written on July 14. In the latter missive, Ballou discusses the weather, his health, soldiers’ food, and the mail service. “I have a square rubber blanket to lay on the ground if it is wet,” he wrote. “I have a large rubber overcoat that reaches to my ankles, a rubber Havelock and my Rubber boots; and if I cannot go through the storms with these I deserve to be wet.” He seems unconcerned about the upcoming campaign: “I do not apprehend fighting on a large scale. [General Winfield] Scott is clenching his fingers and fist so clearly around the Confederates that they must jump and run or be caught; and of course they will run rather than be caught.”

In the authenticated second July 14 letter as well as the others, Ballou dotes on his family: “I was never separated from my children before. I never knew the longing of a father for his children before. And you can scarcely imagine how my blood dances, my nerves thrill and my brain almost whirls…and I see my little boys going through their childish pranks, and hear their singing voices, and even stretch my arms to catch them, and awake to touch the white walls of my tent. O Sarah how often do I think of them…”

If Ballou did not write the letter himself, who did? Is it possible that Horatio Rogers, a fellow attorney and assemblyman, a gifted writer and Ballou’s friend, chose to memorialize the fallen soldier with his own words?

An examination of Ballou’s other letters written from Camp Clark show a positive attitude, not one of concern and impending doom, nor do they offer any insight into Ballou’s reasoning for fighting. Instead of repaying the “great debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution,” Ballou hoped that military service would provide a steady paycheck to his family, and that he could use the connections gained from the service to further his political ambitions when he returned to Rhode Island.

Ballou’s death at First Bull Run was all but forgotten by the average Rhode Islander of the time. Rather, it was the death of Slocum, whose famous last words at Bull Run, “Now show them what Rhode Island can do,” became a rallying cry for Ocean State men to enlist.

Sullivan obviously loved his wife. A letter that included the words in the famous July 14 letter would have of course consoled a grieving widow and offered a strong explanation for why her husband chose to go to war. It also served as an excellent conclusion to the chapter on Ballou’s life in Brown University in the Civil War, encapsulating Rogers’ sentiments that Ballou was a true patriot who had gone to war to support the Union, despite having a much-dependent wife and family at home.

Robert Grandchamp, who writes from Jericho Center, Vt., is an award-winning author of 11 books on U.S. military history, including A Connecticut Yankee at War and Rhody Redlegs.

In Accord

» Shirley Samuels teaches English and American studies at Cornell University. She has written extensively about the Civil War, including “Facing America: Iconography and the Civil War.”

That several letters in Sullivan Ballou’s handwriting have survived, including one purportedly written the same day as the famed one and one five days later, makes it a more comfortable task to think about tone and rhetoric while analyzing them. The man who wrote the obscure examples I had the fortune to read recently was pragmatic, obsessed with details absent in the famous letter. He is determined to return home. He sends specific messages to each of his sons. Yes, he loves his wife very much and he knows about the risks he faces. But he’s not in love with the salvific project of going to war to save the “Government,” as the famous letter declares. In the other missives, he never mentions the government, never capitalizes abstractions, and certainly never refers to his wife, Sarah, as “thee.”

Where the famous letter came from, I cannot presume to say. Someone could have written it specifically to give Sarah comfort in the messy weeks following her husband’s mortal wounding at First Bull Run. Maybe someone wanted to make his death into a redemption of nationalistic beliefs. In other words, the famous letter is written with love and with kindness, but also with a form of emotional manipulation that transmutes personal losses into national sentiment. For that reason, especially when heard with the lilting tones of “Ashokan Farewell” in the background, the letter provides powerful closure to the story that Ken Burns tells in his series. But not for the life of a man whose other dispatches do not use the same language.

In the famous letter, the writer says his “emotions came over me like a strong wind” and turns that simile into metaphor when he suggests that his wife will feel his presence in “the soft breeze.” No such use of similes and metaphors appears in the other letters. They refer to insider concepts such as the “Narragansett shout” that he boasts his men uttered upon finding a vacant camp. The tone that makes the famous letter so powerful does not jibe with the person who offers practical information to his wife: “We left Washington too hurriedly to get my pay and I can send you no money…” That letter is written on Friday, July 19, five days after the supposedly reflective leave-taking of July 14. He does say he loves her in this letter, but he doesn’t refer to the reflections of “my last letter,” as one might expect.

Writing on July 10, Ballou appreciates that his wife’s letters have become longer. He is very methodical, having filed them “all numbered and dated” in order to read them over again. Ballou is ambitious, telling his wife that he desires a promotion. Since Governor William Sprague has a nearby tent, he plans to “improve the acquaintance and make it serviceable to me.” He says that to be “engaged in war” seems like “an excursion as much as anything.” Ballou unabashedly has practical matters on his mind when he tells Sarah, “If you can sell the cow for money—do so and put it in the bank.”

The famous July 14 letter has 19th-century handwriting and sentiment, but the phrases are not the same, nor does the poignancy appear in the other samples. Their tone of intimacy is particular and not abstract. That attention to style accounts for my conviction that Ballou didn’t write the letter. The question of authenticity does not need to adhere to a particular writer. Real feelings emerge here—feelings that explain the emotions felt by so many viewers and that kept Ken Burns enthralled—but I am not convinced they emerge from the same writer whose vivid language fills the other letters. And I am left wondering about how much the persistent attachment to the celebrated letter over time has been caused by the desire to believe that someone had such faith in national government this early in the campaign.