Currently filming in England, the motion picture War Magician will star Benedict Cumberbatch as Jasper Maskelyne, a British illusionist who claimed to have changed the course of World War II. The movie is based on David Fisher’s 2004 biography, which portrayed Maskelyne and his special unit creating fake tank units and a dummy harbor base—even camouflaging the Suez Canal—to fool Nazi forces in North Africa. Although historians have generally dismissed Maskelyne’s claims, he wasn’t the only magician drafted into war efforts. Here are a few others.

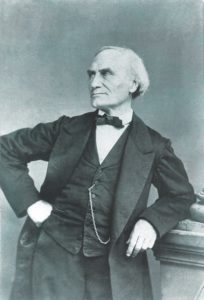

Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805–1871)

Often called “the father of modern magic,” this 19th-century French watchmaker turned illusionist was a European sensation, the first person to prove that magic could succeed as a form of theater entertainment. But Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin’s most intriguing feat of magic may have taken place after he retired from the stage. In Confidences d’un Prestidigitateur, his 1858 memoir, Robert-Houdin claimed that two years earlier French emperor Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte had asked for his help in regaining control of the French colony of Algeria, where traveling Muslim holy men, or marabouts, were inciting rebellion. His mission was clear-cut: to demonstrate that French magic was more powerful than Algerian magic. In several shows in Algeria, Robert-Houdin performed his “Light and Heavy Chest” trick, using under-stage magnets to create the illusion that Algerian tribesmen could be sapped of their strength by the mere wave of a Frenchman’s wand. After several such shows, Robert-Houdin sealed the deal by meeting tribal chiefs in the desert, where he performed the classic magic trick of catching a bullet in his teeth. Algeria remained a French colony for another century, finally winning independence from France in 1962. Was Robert-Houdin’s magic really the reason Algeria stayed so long under French rule? No one can know, but the stage was set for magicians to play a part in war.

Harry Cooke (1844–1924)

Horatio Green Cooke was a teenage schoolteacher when he joined the 28th Iowa Volunteer Infantry to fight in the Civil War. He quickly became known for his marksmanship and excellent handwriting (a highly useful skill in those pre-typewriter days), but also for his knack for gleefully wriggling out of any restraint. After fighting at the Siege of Vicksburg, he became secretary to Union major general Philip Sheridan. Summoned to the War Office in Washington, D.C., Cooke met President Abraham Lincoln and impressed him with an impromptu rope-escape trick. Lincoln immediately appointed Cooke a Federal Scout. Disguised as Confederate soldiers, Cooke and his fellow scouts would slip through enemy lines to gather information. In September 1864, however, during Sheridan’s Shenandoah campaign, Cooke and six other scouts were captured by the notorious Mosby’s Rangers. The Rangers made one mistake: They tied their prisoners to trees overnight. In the dark, Cooke easily slipped free and released the others. He and two comrades eventually made it back to Union lines—but, still wearing Confederate uniforms, they were nearly shot, until by extraordinary coincidence Cooke was recognized by a cousin he hadn’t seen in years. At war’s end, Cooke went to the White House to report to Lincoln, only to be told that the president was at the theater. Cooke ran to Ford’s Theater, bought a ticket, and witnessed Lincoln’s assassination. After his wartime adventures, Cooke became an inventor and touring magician, billed as “Professor H. Cooke, Monarch Supreme of Spirit Mysteries.”

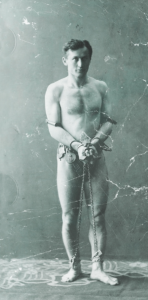

Harry Houdini (Erich Weiss) (1874–1926)

Was Harry Houdini, the great escape artist, really a spy? It’s likely that while performing around Europe between 1900 and 1914, the famous magician did send reports to his friend William Melville, the first chief of British intelligence. Fascinated with the relatively new science of aviation—in 1910, after buying a Voisin biplane, he’d become the 25th person to pilot a powered craft—Houdini could have picked up useful details about Germany’s rapidly growing fleet of aircraft. By the time the United States entered World War I in 1917, however, Houdini was in his early 40s—too old for active duty. (In 1918, as a publicity stunt, he registered for the draft under the name Harry Handcuffs Houdini.) Although he was born in Hungary, Houdini grew up in the United States and loved his adopted country fiercely, so he devoted the war years to fundraising performances, boosting morale and selling more than $1 million in Liberty Bonds. As the president of the American Society of Magicians, he persuaded members to sign a resolution of loyalty to President Woodrow Wilson and inspired other magicians to join the war effort as cryptographers, camouflage experts, and secret agents. He also donated his design for a quick-release underwater diving suit to the U.S. Navy and traveled tirelessly to training camps around the country, teaching soldiers how to escape a sinking ship and how to free themselves from handcuffs, ropes, and manacles. Who knows how many soldiers eluded capture thanks to Professor Houdini’s lessons?

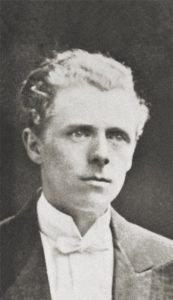

Leslie Harrison Lambert (1883–1941)

In the 1920s and ’30s British audiences were spellbound by the radio tales of A. J. Alan, a pioneering broadcaster whose cultured voice some say became the prototype for the so-called BBC accent. Alan’s fans, however, never knew that he was really Leslie H. Lambert, a buttoned-down employee of the Foreign Office. Lambert’s civil service job had already required him to abandon another career: as a performer of “drawing-room magic” (his audiences included Queen Mary and the Prince of Wales), accomplished enough to be invited to join London’s exclusive Magic Circle. But Lambert’s dual identity in fact disguised more. Since 1914, after a volunteer stint intercepting German transmissions off the Norfolk coast, he’d been recruited to work in Room 40, the Admiralty’s code and cryptography unit, which decrypted some 15,000 enemy communications during World War I. He continued in intelligence work after the war, as a Morse code and traffic analysis expert, in the top-secret Government Code & Cypher School. In 1939 Lambert was among the code breakers—using the alias “Captain Ridley’s shooting party”—who set up Bletchley Park, the top-secret country manor in Buckinghamshire. At Bletchley Park he worked in Hut 8 along with Alan Turing and others assigned to crack Germany’s Enigma Code. Lambert died in 1941, before the code was broken; only much later did the public discover A. J. Alan’s double life.

Harlan Tarbell (1890–1960)

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Harlan Tarbell, a 27-year-old illustrator from Chicago, found himself behind the front lines in France, serving as medic to a kite balloon unit in the 24th Air Regiment. Curious and hard-working, Tarbell made the most of his time in France. Once his superiors discovered his artistic skills, he was assigned to make drawings for a military atlas, and somehow he met the famed impressionist artist Claude Monet, who gave him a few painting lessons. Meanwhile, Tarbell took every opportunity to practice his favorite pastime: performing magic tricks for other soldiers and for their French hosts. Through magic, he became so friendly with local villagers that at the outset of the flu epidemic in 1918, they came to Tarbell—“the magic doctor,” they called him—for help. A great believer in the power of suggestion, he convinced the entire village that no one else would die—and, against all odds, no one did. After the war, in the mid-1920s, Tarbell, by then an art director and part-time professional magician, was hired for his dream job: to write and illustrate a correspondence course for aspiring magicians. Eventually growing to eight volumes, the Tarbell Course in Magic became a best-seller, making “Doc” Tarbell a sought-after magic teacher. (His students included actor and filmmaker Orson Welles, ventriloquist Edgar Bergen, and fellow magicians Harry Blackstone and Harry Houdini.) Over the years, Tarbell invented nearly 200 magic tricks, but none perhaps as great as saving the lives of a whole village.

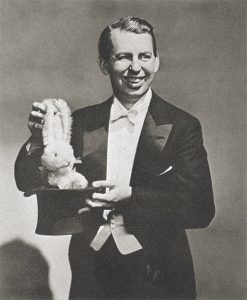

Oswald Rae (1892–1967)

Born in Reading, Berkshire, Oswald Rae enlisted in the Royal Corps of Engineers in 1915 and shipped off to France. Like many of his fellow engineers, Rae was clever at building gadgets, and in his free time he would perform tricks for the other soldiers, delighting them with his humorous patter. Word of his talent spread, and soon he was asked to perform full shows. The war really launched his career—both in France and later in Germany, where he joined the Army of Occupation and presented some 500 wartime magic shows. Field Marshal Herbert Plumer, commander of the British Second Army, singled him out for praise; a pilot who went to one of his shows described him as “screamingly funny.” Once back in England, he worked his way up through variety and vaudeville until he was famous enough to perform exclusively at private society events, appearing before such celebrities as the Prince of Wales and the Queen of Belgium. He also published several books (Practical Patter, Original Magic, Wizardry with Watches); invented Flexible Glass, a device still used by magicians; and founded the British Circle of the International Brotherhood of Magicians. When war broke out again in 1939, Rae was eager to entertain the troops again; too old for active duty, he put together a touring show for the Entertainments National Services Organization. After the war, he returned to society magic shows, performing until shortly before his death.

Richard Valentine Pitchford (Cardini) (1895–1926)

In the mid-20th century, no magician was in greater demand than Cardini, a master at manipulating cards, cigarettes, billiard balls, and other objects. (“His sleight of hand was so good,” another magician observed, “as to be invisible.”) Whether he was playing the White House, Radio City Music Hall, or a royal command performance at the London Palladium, Cardini delighted audiences with his suave routines in evening dress, top hat, and monocle—quite different from the look he sported in his first performances in the trenches of France during World War I. Born in Wales, Richard Valentine Pitchford was just another young mud-caked Tommy, whiling away the endless hours waiting for the next burst of bombs. To amuse his fellow soldiers, Pitchford resorted to his childhood hobby: performing card tricks. Even a battle injury couldn’t stop him: He practiced and performed incessantly while in the hospital. Given the bitter weather of the winter campaigns, he learned to perform sleight-of-hand effects without removing his wool gloves—a facility other magicians would later envy, watching him effortlessly fan out a pack of cards while wearing white dress gloves.

John (Wickizer) Mulholland (1898–1970)

Born John Wickizer in Chicago, John Mulholland started his professional stage career at age 15, eventually becoming a popular author and lecturer, a close friend of Harry Houdini’s, and editor of The Sphinx, the nation’s top magic magazine. He hobnobbed with celebrities and performed often at the White House. Although he never served in the military, in 1944, Armed Service Editions published 100,000 pocket-size copies of his popular book The Art of Illusion: Magic for Men to Do, so soldiers could learn tricks to entertain themselves in camp. In 1953, however, the magic world was surprised when Mulholland retired from editing The Sphinx, citing poor health. The real reason was a deep secret. The Central Intelligence Agency, founded only a few years earlier in 1947, had hired Mulholland as a consultant to advise the agency on techniques of deception, disguise, and misdirection. Mulholland’s work—later published as The Official CIA Manual of Trickery and Deception—included advice on how to send coded signals to clandestine contacts, how to slip a pill into an adversary’s drink, how to surreptitiously pick up a document or book from a table, and how to hide an agent in a secret compartment. Amid the tensions of the Cold War, this CIA initiative—code-named MK-Ultra—even conducted LSD experiments on unwitting servicemen. Whether or not Mulholland ever knew the extent of MK-Ultra’s activities, it was still a strange final chapter to his stellar career as a magician.

John Casson (1908–1999)

John Casson, the oldest son of English actors Lewis Casson and Dame Sybil Thorndike, chose a career in the navy over one in the theater. Becoming a Royal Navy pilot in 1932, he flew some of the first reconnaissance missions of World War II. But on April 9, 1940, while leading an attack on the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst, Lieutenant Commander Casson’s Blackburn Skua dive bomber was shot down over Trondheim, Norway, and he wound up in a German prison camp near Frankfurt. Because of his age and rank, Casson became one of the POW staff, acting as liaison with German camp authorities—as well as secretly helping POWs plot escapes and send coded intelligence reports in their letters home. A talented amateur magician (in London he’d been a member of the Magic Circle), Casson performed tricks to amuse his fellow prisoners and frequently distracted guards with his magic shows. In 1942 he was transferred to Stalag Luft III in eastern Germany, where he helped plan the 1944 mass escape that inspired the movie The Great Escape. At Stalag Luft III, Casson built a small theater for camp entertainments, many of which he produced and directed. Little did the Germans know that the POW “stage crew” was digging an escape tunnel underneath the theater. Casson himself never escaped, returning to England only after the camp was liberated in 1945. Awarded an Order of the British Empire for his wartime exploits, Casson retired from the navy to become a writer and—finally following the family path—a theater producer.

Paul Potassy (1923–2018)

As a boy growing up in Austria and Germany in the 1930s, Paul Potassy loved going to magic shows and learning to perform his own tricks. His parents, however, insisted that he choose a more practical career, so he pursued a degree in engineering—only to have his studies interrupted in 1941, when he was drafted into the German army and sent to the Russian front. Out on patrol one snowy day with a few other soldiers from his unit, he was suddenly struck by enemy gunfire. His companions dropped dead, and Potassy shrewdly decided to lie on the ground in his white camouflage coat, staying as still as possible until the Russians had left. Lying face down with his pistol beneath him, he could hear enemy soldiers approach, prodding nearby corpses and stealing their belongings. Reaching Potassy, they flipped him over and were about to shoot him when he quick-wittedly pulled out a deck of cards he always kept in his coat pocket. “Artist! Artist!” he declared and began to perform card tricks. Intrigued, the soldiers took him prisoner instead of killing him. For the next four and a half years, he lived in prison camps, charming his captors with sleight-of-hand tricks. (A trick he performed with tiny balls of bread helped him sneak extra food when rations were scarce.) After the war, Potassy abandoned engineering and did what he’d always wanted to do: perform his magic act on the nightclub circuit in Europe and Asia.

Holly Hughes, a former executive editor of Fodor’s travel publications, is a New York–based writer and editor.

This article appears in the Summer 2021 issue (Vol. 33, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Poetry | Ode to a Patriot