The surrender Sherman and Johnston crafted at Bennett Place was monumental.

It very nearly never happened.

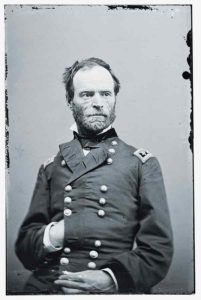

News of Robert E. Lee’s April 9, 1865, surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House reached Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman at 5 a.m. April 12. Sherman and his army group, the Military Division of the Mississippi, had just completed one of the most remarkable campaigns in military history, having stormed through the Carolinas like “a plague of locusts” in February and March, and were now perched outside the North Carolina capital of Raleigh, ready to close the deal on General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of the South.

“I hardly know how to express my feelings, but you can imagine them,” Sherman told Grant in a telegram. “The terms you have given Lee are magnanimous and liberal. Should Johnston follow Lees example I shall of course grant the same. He is retreating before me on Raleigh, but I shall be there tomorrow. Roads are heavy [from the rain], but under the inspiration of the news from you we can march twenty-five miles a day…”

Naturally, Sherman’s troops celebrated wildly upon hearing the news later that day, but Sherman still could not be certain how Johnston or the Confederate government would respond. And when the Federals entered Raleigh on April 13, they discovered that Johnston and his men had already begun moving to the west, toward Greensboro, roughly 70 miles away. Any chance of peace would have to wait at least another few days.

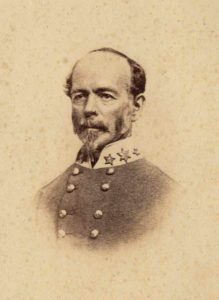

Johnston, though, realized it was time to put “a stop to the needless sacrifice of life” and reached out to Sherman to discuss peace terms. On April 17 the two met at James Bennett’s 350-acre farmstead in Durham’s Station, a rail stop between Raleigh and Greensboro. What evolved over the next nine days would prove to be one of the most extraordinary periods in our nation’s history and also cemented an improbable friendship between the two generals, who had never met before in person.

As the sun set on April 18, a surrender document Sherman and Johnston had signed promised the end of four years of civil war. The venerable generals would learn soon enough it wouldn’t be that easy.

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n April 20 Sherman sent his adjutant, Major Henry Hitchcock, to Washington, D.C., to deliver the surrender document personally to Grant. While waiting for instructions from the capital, Sherman used his time wisely. “[R]epairs on all the railroads and telegraph-lines were pushed with energy, and we also got possession of the railroad and telegraph from Raleigh to Weldon, in the direction of Norfolk,” he wrote his wife, Ellen. And, should their deal collapse, he also carefully positioned his forces at key points around Johnston’s army so he could deliver a coup de grâce if necessary.

Union soldiers reacted with both joy and uncertainty at the news. “The Angel of Peace has spread his wings over our country once more,” declared a 3rd Wisconsin soldier. “It was a glorious day for us who have seen the thing through from the beginning to the end.” But a 20th Illinois soldier expressed the prevailing anxiety in the army for new President Andrew Johnson: “He is deemed as too passionate dissipated and unstable for so responsible a position at so critical a period.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“I believe, if the South would simply and publicly declare that slavery is dead, you would inaugurate an era of peace and prosperity that would soon efface the ravages of the past four years of war.” -Gen. William T. Sherman[/quote]

On April 21 Sherman addressed an important issue in a letter to Johnston. “It may be the lawyers will want us to define more minutely what is meant by the guaranty of rights of person and property,” he wrote. “It may be construed into a compact for us to undo the past as to the rights of slaves and leases of plantations on the Mississippi, of vacant and abandoned plantations. I wish you would talk to the best men you have on these points and if possible let us in the final convention make these points so clear as to leave no room for angry controversy.

“I believe, if the South would simply and publicly declare what we all feel, that slavery is dead, that you would inaugurate an era of peace and prosperity that would soon efface the ravages of the past four years of war.”

Allowing that Confederate morale had collapsed, Johnston later noted that their meeting “and the armistice that followed, produced great uneasiness in the army. It was very commonly believed among the soldiers that there was to be a surrender, by which they would be prisoners of war, to which they were very averse. This apprehension caused a great number of desertions between the 19th and 24th of April—not less than four thousand in the infantry and artillery, and almost as many from the cavalry; many of them rode off artillery horses, and mules belonging to the baggage-trains.”

Lieutenant General William J. Hardee, Johnston’s senior subordinate, who had remained with the army’s main body at Greensboro, wrote to General P.G.T. Beauregard: “We are all agog respecting the object [of the truce], and surmises are that negotiations are afoot between Johnston and Sherman. If such be not the case, it would be well for me to know it as soon as practicable, that I may contradict it. The report, as you may well conceive, can do our troops no good.”

Johnston’s men harbored no illusions. “Everything seems to indicate a speedy termination of the Confederacy & a restoration of the old state of affairs which though it is very humiliating to us still has its pleasant features,” staff officer G.P. Collins admitted on April 22. “Everyone is so worn out with war & I am almost inclined to believe that our people scarcely deserve freedom or they would stand up better.”

Confederate President Jefferson Davis took the opportunity to poll his Cabinet on their views on the terms Sherman and Johnston had negotiated on April 18. All favored making peace on the best terms possible, including Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, who earlier had supported attempts to continue the war.

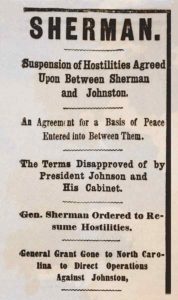

Cabinet members in Washington were stunned, however, when Grant read Sherman’s communications, particularly Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, whom Sherman had assured a few days earlier, “I will accept the same terms as General Grant gave General Lee, and be careful not to complicate any points of civil policy.”

Stanton told Grant: “You will give notice of the disapproval to General Sherman and direct him to resume hostilities at the earliest moment….The President desires that you proceed immediately to the headquarters of General Sherman and direct operations against the enemy.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“I sent Sherman to do this himself. I did not wish the knowledge of my presence to be known to the army generally.” -Gen. Ulysses S. Grant[/quote]

The disapproval memorandum the Cabinet issued was soon published in several newspapers. Among concerns the members had stated were that restoration of the “rebel authority” in the respective states would enable them to reestablish slavery, and that it “formed no poises of true and lasting peace, but relieved rebels from the pressure of our victories and left them in condition to renew their effort to overthrow the United States Government…”

The displeased Cabinet, it seemed, was determined to publicly embarrass Sherman for trying to end the war. Grant was soon on his way to meet Sherman, escorted by several of his officers as well as Hitchcock. Not sure what he’d learn, Sherman cabled Johnston that evening to be ready to resume negotiations. “There is great danger of the Confederate armies breaking up into guer[r]illas,” he conferred in a letter to Ellen, “and that is what I most fear. Such men as Wade Hampton, [Nathan B.] Forrest, Wirt Adams, etc., never will work and nothing is left for them but death or highway robbery.”

Sherman wrote he was “both surprised and pleased” to see Grant in the flesh, only to learn that his terms with Johnston had been disapproved. He was to give his opponent “48 hours notice and then attack or follow him.”

Grant advised Sherman that he was authorized to offer the same terms to Johnston as he had given to Lee at Appomattox, noting, “I sent Sherman to do this himself. I did not wish the knowledge of my presence to be known to the army generally; so I left it to Sherman to negotiate the terms of the surrender solely by himself, and without the enemy knowing that I was anywhere near the field.”

Sherman immediately notified Johnston of the 48-hour notice. A few minutes later, he sent a second dispatch: “I am instructed to limit my operations to your immediate command and not to attempt civil negotiations. I therefore demand the surrender of your army on the same terms as were given General Lee at Appomattox, of April 9, instant, purely and simply.” Sherman then instructed Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson in Georgia to make arrangements to resume hostilities on April 26. He also drafted orders for his army to prepare to move on Johnston’s command as soon as the truce expired.

Union public opinion clearly differed with Sherman. Enraged by Lincoln’s assassination, Northerners wanted to show the Confederates no mercy. Stanton took the extraordinary step of allowing Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck to prepare and issue an order advising Union commanders in Virginia, Georgia, and Alabama “to pay no regard to any truce or orders of General Sherman suspending hostilities, on the ground that Sherman’s agreements could bind his own command only, and no other. They are directed to push forward, regardless of orders from any one except General Grant, and cut off Johnston’s retreat.” Sherman never forgave Halleck for issuing such a command.

New York newspapers, in particular, railed against Sherman. “[T]he distinguished and admirable soldier, has fatally compromised himself, we fear, in entering into the forbidden field of diplomacy as a peacemaker,” the New York Herald declared. “The astounding dispatches from the War Department…place the conqueror of Georgia and South Carolina in a truly unfortunate position.”

The paper also opined: “We have heard him as a soldier, and justly too, ranked with that great military genius, the Duke of Marlborough. The parallel may now be extended to the blunders of the great Duke as a politician, with this difference: that he never committed such a great political blunder as this peace protocol….From the country at large he has cast his political fortunes into the peace democracy—a poor and contemptible faction.”

Grant understood Sherman’s anger at the media firestorm. “Sherman, from being one of the most popular generals of the land…was denounced by the President and Secretary of War in very bitter terms,” he wrote. “Some people went so far as to denounce him as a traitor—a most preposterous term to apply to a man who had rendered so much service as he had….”

Not all of Sherman’s men supported his actions. As New Yorker Peter Eltinge wrote his father: “What do you think of the Sherman–Johnston agreement? I was never more surprised in my life when I read the Agreement….He has certainly lowered himself much in the opinion of the whole Army and a majority of Loyal citizens. The credit and renown that he had won by his great campaign has nearly all been lost by his attempting to make himself a great Peacemaker.”

In a letter to Stanton on April 25, an angry Sherman admitted “my folly in embracing in a military convention any civil matters, but unfortunately such is the nature of our situation that they seem inextricably united.…I still believe the Government of the United States has made a mistake, but that is none of my business; mine is a different task, and I had flattered myself that by four years patient, unremitting, and successful labor I deserved no reminder such as is contained in the last paragraph of your letter to General Grant. You may assure the President I heed his suggestion.”

Major General Carl Schurz, serving as Army of Georgia commander Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s temporary chief of staff, accompanied Slocum to a meeting at Sherman’s Raleigh headquarters and watched as Sherman “paced up and down the room like a caged lion, and, without addressing anybody in particular, unbusomed [sic] himself with an eloquence of furious invective which for a while made us all stare.”

April 18 Surrender Terms*

Memorandum or basis of agreement made this 18th day of April, A.D. 1865, near Durham’s Station, in the state of North Carolina, by and between General Joseph E. Johnston…and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman…

- First. The Contending armies now in the field to maintain the status quo until notice is given by the commanding general of any one to its opponent…

- Second. The Confederate armies now in existence to be disbanded and conducted to their several State capitals, there to deposit their arms and public property in the State Arsenal, and each officer and man to execute and file an agreement to cease from acts of war and to abide by the action of both State and Federal authority…

- Third. The recognition by the Executive of the United States, of the several State governments, of their officers and legislatures taking the oaths prescribed by the Constitution of the United States, and where conflicting state governments have resulted from the war the legitimacy of all shall be submitted to the [U.S.] Supreme Court.

- Fourth. The re-establishment of all the Federal courts in the several States, with powers as defined by the Constitution and laws of CongreSs.

- Fifth. The people and inhabitants of all the States to be guaranteed, so far as the Executive can, their political rights and franchises, as well as their rights of person and property, as defined by the [U.S.] Constitution and of the States respectively.

- Sixth. The Executive authority of the Government of the United States not to disturb any of the people by reason of the late war so long as they live in peace and quiet, abstain from acts of armed hostility, and obey the laws…at the place of their residence.

- Seven. In general terms, the war to cease, a general amnesty, so far as the Executive of the United States can command, on condition of the disbandment of the Confederate armies…and the resumption of peaceful pursuits by the officers and men hitherto composing said armies.

*Full versions of April 18 and April 26 surrender documents available on historynet.com

As Sherman fumed, the picture for the Confederates was coming into focus. On the afternoon of April 24, after reading the letters from his remaining Cabinet officers encouraging him to accept the terms, Davis gave Johnston his approval, though he remained convinced the Union government would not approve the convention since it declared amnesty for the Confederate civilian authorities.

When he saw Sherman’s dispatches, Johnston immediately reported to Confederate Secretary of War Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge and requested instructions. Johnston suggested disbanding the army to prevent Union armies from further devastating the countryside.

Replied Breckinridge: “Does not your suggestion about disbanding refer to the infantry and most of the artillery? If it be necessary to disband these they might still save their small-arms and find their way to some appointed rendezvous. Can you not bring off the cavalry and all of the men you can mount from transportation and other animals, with some light field pieces? Such a force could march away from Sherman and be strong enough to encounter anything between us and the Southwest.”

Johnston remained convinced his was the correct approach. “We have to save the people, spare the blood of the army, and save the high civil functionaries,” he replied. “Your plan, I think, can only do the last. We ought to prevent invasion, make terms for our troops, and give an escort of cavalry to the President, who ought to move without loss of a moment. Commanders believe the troops will not fight again.”

After consulting with Beauregard, who agreed with his course, Johnston told Davis he would meet with Sherman to discuss surrendering his command.

“It is useless to deny that the officers and men of the army were chagrined and disappointed at this result,” said one of Sherman’s adjutants, Major George W. Nichols, at the possibility the truce would end. Noted Hitchcock: “Everyone anticipates, and I think everyone regrets, another march, for this time, if the Army does advance, it is necessarily in pursuit not of a single object, as heretofore, or to reach a definite ‘objective point,’ but to pursue a flying enemy and meanwhile to live on the country.”

A 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry soldier, of Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jordan’s brigade of Kilpatrick’s division, noted, “The men of the Regiment were very willing to resume hostilities, if it was necessary to do so….But there was not a soldier in the Regiment but that felt that it would be cruelty to fight another battle. Every man was conscious of the fact that the war was really over; but orders were orders, and they were ready to resume hostilities.”

About 6 p.m., however, Sherman received Johnston’s dispatch by courier. A third meeting between the two was scheduled for noon the next day at the Bennett House.

Still incensed by the poor treatment he’d received from Stanton, Halleck, and the press, Sherman brusquely boarded a train to Durham’s Station the morning of April 26, accompanied by two of his army commanders—Maj. Gens. John M. Schofield and O.O. Howard—and Maj. Gen. John Logan. When Sherman and his entourage arrived at Bennett Place, however, Johnston was not there. His train was running late because of an accident.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“They seemed apprehensive that the terms of Grant and Lee, pure and simple, could not be executed, and that if modified at all…would meet with a second disapproval.” -Maj. Gen. John Schofield[/quote]

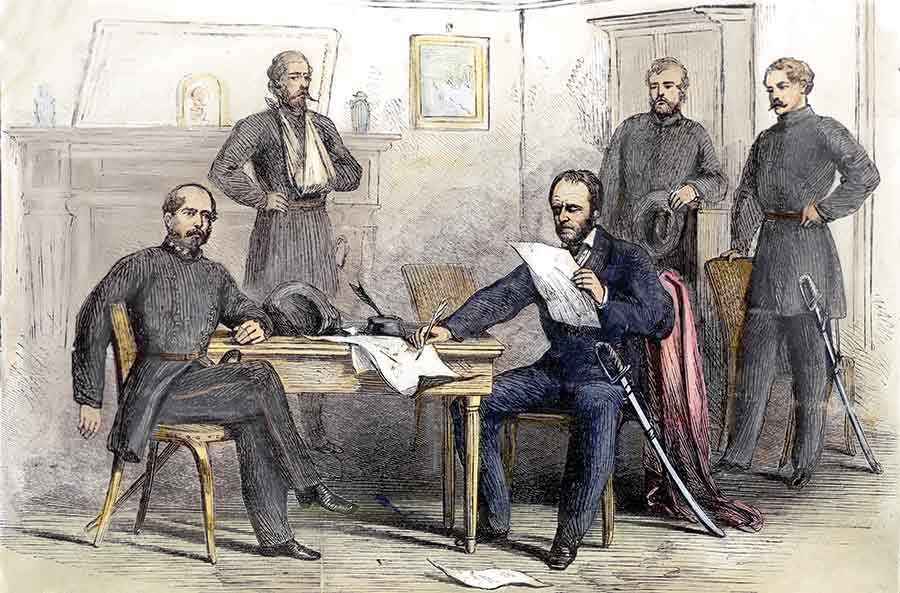

Johnston finally arrived about 2 p.m. The commanding generals greeted each other warmly, then retired to the Bennett House. Sherman again stressed that he could offer only Appomattox-parallel terms, but Johnston felt that those alone were inadequate and requested additional guarantees for his men’s safety. Though he acknowledged additional terms were likely needed, Sherman feared his government would reject anything that deviated as such. The commanders could not reach a resolution.

“At length I was summoned to their presence, and informed in substance that they were unable to arrange the terms of capitulation to their satisfaction,” Schofield, Sherman’s second-in-command, later wrote. “They seemed discouraged at the failure of the arrangement to which they had attached so much importance, apprehensive that the terms of Grant and Lee, pure and simple, could not be executed, and that if modified at all, they would meet with a second disapproval.” Schofield suggested preparing two documents: One would encompass only the Appomattox terms, and the second would be supplemented by Johnston’s concerns.

Schofield said Sherman “intimated to me to write, pen and paper being on the table where I was sitting, while the two great antagonists were nervously pacing the floor….I at once wrote the ‘military convention’ of April 26, handed it to General Sherman, and he, after reading it, to General Johnston.”

As department commander, Schofield explained, he could do all that might be necessary to remove any obstacles that hindered consummation of the agreement once Sherman left for Washington. The two officers signed the first document; when he handed it to Sherman, Johnston declared, “I believe that is the best we can do.”

That night Grant endorsed the terms so no questions would arise about their acceptability. Schofield later recalled he overheard Grant declare that “the only change he would have made would have been to write General Sherman’s name before General Johnston’s. So would I if I had thought about it; but I presume an unconscious feeling of courtesy toward a fallen foe dictated the order in which their names were written.”

After drafting the initial terms, Schofield prepared supplemental terms based on his discussions with Johnston. Those included provisions that Confederate troops would retain their transportation; that each brigade or separate body would “retain a number of arms equal to one-seventh of its effective total, which, when the troops reach their homes, will be received by the local authorities for public purposes; and that troops from Arkansas and Texas were to be transported by water from Mobile or New Orleans to their homes by the United States.

Neither Grant nor the civil authorities in Washington disputed any of the provisions. Thus, Joe Johnston, convinced that it would be “the greatest of human crimes to continue the war,” surrendered nearly 90,000 Confederate soldiers located in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, disobeying President Davis’ specific orders by doing so. Although some Confederate soldiers remained in the field after the events at Bennett Place, Johnston had arranged the largest surrender of Southern troops.

With their difficult work finally finished, Sherman and Johnston invited James Bennett and their officers to join them for a toast. The two commanders introduced their subordinates. Johnston had brought with him Maj. Gen. Matthew C. Butler, a protégé of Hampton and a handsome young lawyer who had lost his right foot to a Union artillery shot at the June 9, 1863, Battle of Brandy Station in Virginia. Brigadier General Thomas M. Logan, who commanded Butler’s former brigade of South Carolinians, also accompanied Johnston.

Schofield arranged for the delivery of 250,000 rations—representing 10 days rations for 25,000 men—to Johnston’s army, along with wagons to haul them. Sherman hoped to prevent the newly surrendered Confederate troops from stealing from their own people. Now that the Confederates were their countrymen once more, the Union high command did all it could to ensure that they were well treated while the Southerners waited to give their paroles; the Union officers also made sure that the soldiers had sufficient weapons to keep the peace and to protect private property.

The enlisted men of both sides mingled freely while the generals worked out the final details of the surrender. “I talked with many of the Yankee soldiers who told me they were glad the war was over, glad we would not have to kill each other any more,” a Rebel recalled years after the war. “I do not think Sherman was as mean as he has been pictured, for he gave us our horses and side-arms and every fourth man ammunition and told us to go home…and go to work.”

In the meantime, while the Federal armies remained in place pursuant to Sherman’s orders, the Confederate army continued its retreat until Beauregard halted at about 1:30 p.m. However, Johnston’s soldiers deserted in droves, determined to go home before receiving their paroles. “May I ever be spared such a sight as I witnessed when the order to move was given,” a North Carolinian noted. “Whole regiments remained on [camp]ground, refusing to obey.” Stragglers threw away their weapons, prompting orders to be issued that only those with weapons would be provided rations. “We were overpowered but not subdued,” the proud Southern soldiers declared.

After he and Johnston parted, Sherman telegraphed Grant of the outcome. Grant readily acknowledged that this was Sherman’s moment of triumph. Knowing his dear friend deserved to savor the victory, he wisely chose to remain back in Raleigh.

“Thus was surrendered to us the second great army of the so-called Confederacy, and though undue importance has been given to the so-called negotiations which preceded it, and a rebuke and public disfavor cast on me wholly unwarranted by the facts,” a defiant Sherman wrote. “I rejoice in saying it was accomplished without further ruin and devastation to the country, without the loss of a single life to those gallant men who had followed me from the Mississippi to the Atlantic, and without subjecting brave men to the ungracious task of pursuing a fleeing foe that did not want to fight. As for myself, I know my motives, and challenge the instance during the past four years where an armed and defiant foe stood before me that I did not go in for a fight, and I would blush for shame if I had ever insulted or struck a fallen foe.”

Union soldiers waited impatiently to hear what had happened at the Bennett House, as rumors flew rampantly. News of the surrender did not reach all of them at the same time. Soldiers at the station in Raleigh were left to wait until officials on a train had reached General John Logan’s headquarters two miles farther down the track. “All was silent,” a Wisconsin soldier recalled. “And then—a long and protracted cheer. A few seconds later, cheers broke out a little nearer to us. There were renewed cheers as the tidings flew toward us from regiment to regiment. We knew well enough what the result of the conference had been, yet we were very anxious to hear it directly.” A few minutes later, a lieutenant declared, “Boys, the thing is all settled, and we are to march back to Raleigh in the morning.”

Hitchcock, who had played such an important role during the negotiations, waxed philosophically that night. “It will be a hundred times harder for me now to remain in the service [than] when we were deep in the mud and swamps of South Carolina or in front an enemy near [Averasboro] and Bentonville,” he told his wife. “There was something like a definite object there; for the sort of occupation or want of occupation I look forward to now I confess I have no relish, especially the loafing part of it. However, the war is over now, thank God, in its breadth and strength.”

While all were excited that the war was indeed finally over, not everyone agreed about the outcome. That night, in fact, Halleck sent a dispatch to Stanton indicating that the orders that had angered Sherman remained in place: “Generals Meade, Sheridan, and Wright are acting under orders to pay no regard to any truce or orders of General Sherman suspending hostilities, on the ground that Sherman’s agreements could bind his own command only, and no other. They are directed to push forward, regardless of orders from any one except General Grant, and cut off Johnston’s retreat.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“Sherman has fatally compromised himself, we fear, in entering into the forbidden field of diplomacy as a peacemaker” -New York Herald[/quote]

Grant, however, acted quickly to correct that. Sherman continued to stew over his treatment by the high command. He defended his actions in a report he drafted on May 9. “I still adhere to my then opinions, that by a few general concessions, glittering generalities, all of which in the end must and will be conceded to the organized States of the South, that this day there would not be an armed battalion opposed to us within the broad area of the dominions of the United States,” he wrote. “Robbers and assassins must in any event result from the disbandment of large armies, but even these should be and could be taken care of by the local civil authorities without being made a charge on the national treasury.”

As Major Nichols later wrote, “The evidence goes to show that Johnston has been induced to surrender quite as much by the discontent and threats of his own soldiers as by the Federal force in his rear. The Rebel troops see the utter folly of further resistance, and refuse to fight longer. Johnston has pursued the only wise course left open to him.”

When Johnston finally made it to his Greensboro headquarters, he sent telegrams to governors of the various states of the Confederacy explaining his actions. “The disaster in Virginia, the capture by the enemy of all our workshops for the preparation of ammunition and repairing of arms, the impossibility of recruiting our little army opposed to more than ten times its number, or of supplying it except by robbing our own citizens, destroyed all hope of successful war,” he wrote.

He would go to his grave 26 years later still confident he had done the right thing for his men and for his country.

An attorney by day in Columbus, Ohio, Eric J. Wittenberg is an award-winning Civil War historian, speaker and tour guide, and the author of several Civil War titles, including Out Flew the Sabres: The Battle of Brandy Station. A native of southeastern Pennsylvania, he has been hooked on the Civil War since a third-grade visit to Gettysburg.

Adapted with permission from We Ride a Whirlwind: Sherman and Johnston at Bennett Place, by Eric J. Wittenberg (Fox Run Publishing, 2017).