About mid-morning on a “Warm and Plesent” Christmas Eve in 1862, Union Colonel William H. Graves peered through field glasses at what looked to be “three brigades” of Confederate cavalry or mounted infantry maneuvering through fields and scattered timber just east of Middleburg, Tenn. The 26-year-old Graves commanded the 12th Michigan Infantry garrison there. Only 115 officers and men comprised his ranks in town. The balance of his command occupied small guard posts along the Mississippi Central Railroad, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s main avenue of supplies for his first offensive against the Rebel bastion at Vicksburg, Miss.

Young Graves knew the odds were heavily stacked against him when he spied an enemy horseman approach under a flag of truce. “I met the bearer a short distance in front of my block-house,” he recalled.

“Who is in command?” demanded the enemy rider, a cavalry staff officer.

“I am,” Graves replied. In a holiday spirit, perhaps, Graves had been “playing ball” with some of his men earlier that morning and wore a plain fatigue coat without any sign of rank. His pants were carelessly tucked into his boots.

The Confederate surveyed Graves “from head to foot” and then demanded “an unconditional and immediate surrender in the name of Colonel Griffith commanding [the] Texas brigade.”

“I did not like the manner of the bearer of the flag,” Graves recalled. “He appeared pompous and overbearing…” Graves replied that he “would surrender when whipped, and that while he was getting a meal we would try and get a mouthful.”

“That is what you say, is it?” replied the flag-bearer.

“That is what I say,” returned Graves.

At this, the gray-clad rider abruptly wheeled his mount and spurred back to his lines. Graves hurried over to a crude breastwork his men had fashioned of thick wood planks. The gritty colonel had scarcely joined his men inside the rough timber strongpoint when bullets began to fly.

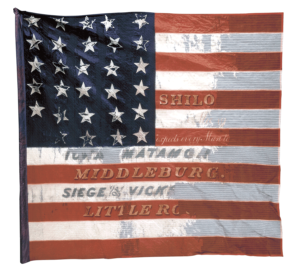

The 12th Michigan had already faced its share of adversity before coming to Middleburg early in November 1862. Mustered into United States service nearly a thousand strong on March 5, 1862, the regiment was assigned to the Army of the Tennessee at Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., part of Everett Peabody’s 1st Brigade in Brig. Gen. Benjamin M. Prentiss’ 6th Division. The Wolverines’ campsite was among the first targets hit during the massive Confederate assault that opened the Battle of Shiloh on April 6. “[W]e were drove back,” a Michigan private lamented, “they took all of our clothing.” Later that day, the 12th was in the vortex of combat in the Hornets’ Nest “amid the most dreadful carnage.”

After the battle, minus the fresh clothing and camp equipment that had fallen into enemy hands, the regiment suffered through days of wet, chilly weather. Diarrhea and dysentery swept its ranks. When the Federal army under Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck began to advance on Corinth, Miss., in late April, the 12th’s regimental surgeon reported that “just over three hundred men were able to go forward.”

The regiment also had suffered under the frightful leadership of Colonel Francis Quinn. A political appointee lacking military and social skills, Quinn abused subordinates and enlisted men alike. The regiment’s quartermaster, a Quinn selection bent on personal gain, also neglected the soldiers’ welfare. In a July 1, 1862, report about the regiment, corps commander Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand wrote, “They are undisciplined, disorganized, and deficient in numbers.”

When word of the regiment’s plight reached the Michigan state capital, Governor Austin Blair fired a sharp telegram to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Blair condemned Quinn as “the worst colonel I ever saw [who] has made more trouble than all the rest put together.” The specter of court-martial compelled Quinn and others of his staff to resign. Command of the 12th Michigan then passed to Lt. Col. William H. Graves.

The battle-tested Graves had served as captain in the 1st Michigan Infantry (a three-month unit) and had been wounded July 21, 1861, while on the firing line at First Bull Run. Described as “kind yet firm, sympathetic and brave,” Graves quickly revived the 12th Michigan. He led the regiment to Bolivar, Tenn., arriving by July 18, 1862.

The seat of Hardeman County, Bolivar perched on a bluff where the Mississippi Central Railroad spanned the Hatchie River. The once-picturesque town was now a fortified supply hub and hive of military activity for the Union advance in western Tennessee.

Bolivar was also home to a bustling “contraband” camp, with hundreds of freedmen employed to erect fortifications around the cantonment. “[T]heir faces were the only pleasant ones we saw when we entered the town,” recalled Samuel H. Eells, the 12th Michigan’s hospital steward. “[T]hey come into the camp every day bringing corn-cakes, pies, buttermilk, eggs and etc.” Eells’ conduct with the former slaves would take a disturbing turn in weeks to come.

The importance of Bolivar to Grant’s advance in western Tennessee and northern Mississippi made the town a prime target. A mix of Confederate regular and partisan forces preyed on the tenuous rail network. “Every foot of the railroad had to be vigilantly watched to prevent it from being torn up,” noted a Federal soldier. “One man with a crow-bar…could remove a rail…and cause a disastrous wreck…” Within days of the 12th’s arrival at Bolivar, mounted gray raiders struck the depot at Hickory Valley, only 10 miles south of town, leaving it “a smouldering ruin.”

Graves shifted his men from one hot spot to another as guerrilla activities dictated. Even shuttling to new locations via the very railroads they guarded became risky. On September 24, “a bunch of the 12th Michigan…were frightfully crushed and mangled…” when the rails suddenly parted for an undetermined reason and the flatcar they were riding “was torn to splinters.”

Soon after the accident, the regiment was on the move again. Toting three-day rations, the Wolverines trudged southeast with Maj. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut’s division at daylight on October 4. They moved to the sound of “heavy firing” from the fighting at Corinth. “Marched all day went for miles,” wrote Private Clark Koon of Company G, “[and] had a squrmish with the Rebles Advance killing thre and taking 40 prisioner [sic].”

The Michiganders covered more than 20 miles that day as General Hurlbut struck units of Confederate Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn’s Army of West Tennessee near Pocahontas, Tenn. Van Dorn was on the run after the Confederate retreat at Corinth when the Federals confronted his troops at Davis’ Bridge over the Hatchie River.

Koon recalled the next morning’s contest at the crossing:

“[W]e got down to the river…while the rebles wer throwing their shells over us When Gen Hulburt came up to Col Graves and sayed who will volenteer to cross the Brig for their is non will go Col Graves sayed his 12 Mich would if the Dr L. [Dear Lord] stands before them and over we went while the Enemy was pouring their Grape & Canister over us but we Gained the hights and in less then a [h]our the field was ours.”

The 12th Michigan was praised for its “prompt, fearless, and energetic conduct” at Davis’ Bridge, but there were 570 Union casualties and Van Dorn had managed to escape.

On the heels of the Union victories at Corinth and Davis’ Bridge, Grant drove deeper south. By November 4, bluecoats occupied key transport centers at La Grange and Grand Junction, Tenn. That same day, the 12th Michigan occupied Middleburg, Tenn.

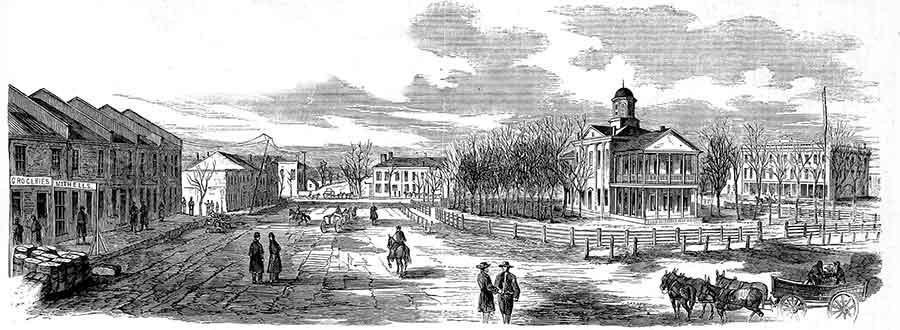

A Methodist Church, a brick hotel, and a two-story “brick store, owned…by a near relative of President James K. Polk” formed the heart of Middleburg. A post office, “a number of log stores, a small woolen mill…blacksmith shops, several saloons,” and various dwellings extended the town along the main road. Beyond the settlement, a lattice of woodlots and farmland covered rolling countryside. Cotton was the main crop in the region. Bales were loaded on railcars from a sturdy wooden platform close to town.

Graves made it clear to his men that they would be staying at Middleburg for a while. They were responsible for guarding the rails seven miles north to Bolivar and three miles south to the town of Hickory Valley—an occupation that produced mixed feelings. A bitter townsman recalled, “Soldiers stacked their arms about the log school house…while the pupils were inside reciting.” Another chronicler bemoaned the 12th “as devilish a lot as ever came South.” Eells, however, helped out by tending to civilian patients, noting, “The doctors here are a poor set…”

Eells, though, resorted to some extreme medical practices while in Middleburg. In an upper room of the Methodist Church serving as regimental hospital, the medical staff routinely kept a cadaver “or two.” The corpses were obtained from Bolivar’s contraband camp, where Eells revealed, “they are dying at the rate of three or four a day.” In a letter home on November 25, Eells admitted he was “going into dissection pretty strong” to enhance his surgical skills.

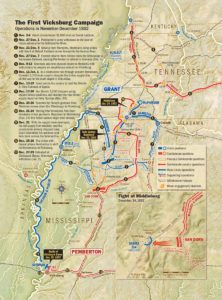

Meanwhile, the bulk of Grant’s army pressed into northern Mississippi. By December 3, Grant established his main supply depot at Holly Springs, 20 miles south of the border. Each southward step Grant took increased the risk to Middleburg and other posts on his railborne lifeline.

Graves received a blunt directive from his district commander, Brig. Gen. Jeremiah C. Sullivan, on December 3: “[G]uerrilla bands are moving with intention of burning railroad stations, tanks, and bridges…attack will be sudden but must be repelled.” Possibly in response to this dictate, Graves had loopholes cut in the walls of the hotel and store. Barricades went up at windows and doors. And the cotton-loading platform beside the railroad was converted to a rude fortification. Planks were “taken from the top,” an officer recalled, “and put around the sides.” The double timbers were then cut to accommodate the regiment’s Austrian rifle-muskets, and a “small log house formerly used for a grocery” became a strongpoint.

In mid-December, Federal works at Middleburg and elsewhere were put to the test when Rebel forces launched concerted efforts to stop Grant.

Confederate Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, responsible for defending Vicksburg, first blocked Grant’s progress just below Oxford, Miss. He then launched three mounted brigades—3,500 men—under Van Dorn 30 miles behind the Federals. The architect of the raid, Lt. Col. John S. Griffith, commanded the 1st Texas Brigade; Colonel William H. “Red” Jackson led a small brigade of Tennesseans; and Colonel Robert “Black Bob” McCulloch had a regiment each from Missouri and Mississippi.

Van Dorn surprised and obliterated Grant’s main supply base at Holly Springs on December 20. After reducing $1.5 million worth of Yankee goods to cinders, the raiders galloped north that night. The next day, they cut telegraph wires, ripped up rails, and attacked isolated Union outposts. Many of the Rebels were garbed in captured blue overcoats. “The men rode…in high glee,” recalled one raider.

When December 22 dawned, Van Dorn’s jubilant horsemen were across the Tennessee state line. Skirting the Yankee strongpoint at Grand Junction, Van Dorn harassed enemy posts at La Grange, Moscow, and Somerville. The next evening, the Confederates bivouacked along Clear Creek, five miles northwest of Bolivar. “It was said,” wrote a Tennessee cavalryman, “we would repeat the Holly Springs business at Bolivar…and there spend a jolly Christmas.”

At Middleburg on December 22, Graves sent a note to Colonel John W. Sprague, in temporary command at Bolivar, warning “that a large force of rebels are marching on this way.” He also put the 12th Michigan on alert. Enemy cavalry was prowling. Despite the warning, Koon penciled in his diary the next day that “John Ploof ”—from Koon’s Company G–—was “taken pris and Perrowled.”

On Christmas Eve, Koon and Companies D, E, G, and K of the 12th “got reddy for the Reb again at 5 A.M.” They stockpiled water and extra munitions in their crude wooden redoubt. When tensions eased somewhat, Graves joined his men in a game of baseball, and Lt. Col. Dwight May of his staff left for Bolivar to attend a “military commission.”

About two miles from town, May saw horsemen approaching, clad in blue overcoats. Alerted by the “suspicious movements” of the riders, and the “peculiar gait” of their mounts, May reined his horse to use his field glasses for a closer look. That drew gunshots from the strangers and shouts for him to halt. May promptly reversed course and galloped back to Middleburg.

May had run smack into an advance party of Van Dorn’s troopers from Bolivar, donned in uniforms they had pilfered from Holly Springs. After discovering that Bolivar had been reinforced overnight by Union Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson’s brigade of cavalry and was now too well-fortified for direct assault, Van Dorn instead feigned an attack before sunrise and passed through the western outskirts of town. He had also dispatched a strong column under Colonel Griffith to strike directly at Middleburg.

May, on a fresher horse, reached Middleburg well ahead of Griffith’s advance riders and sounded the alarm. Michigan riflemen scrambled to their prepared positions while the quartermaster “sent his teams and such stores as could be thrown on the wagons out of the way.” Grabbing his field glasses, Graves hurried to a nearby rise for a better look. “[T]he Rebles have come at last,” Koon scribbled in his diary.

Graves trained his glasses on the sparse December landscape east of Middleburg, when “the enemy appeared in line of battle as infantry.” He soon spotted the enemy envoy approaching on horseback with white flag in hand, “thinking, I suppose, they had a sure thing on us.” As soon as their brief, fruitless meeting ended, Graves “double-quicked it to the block-house.”

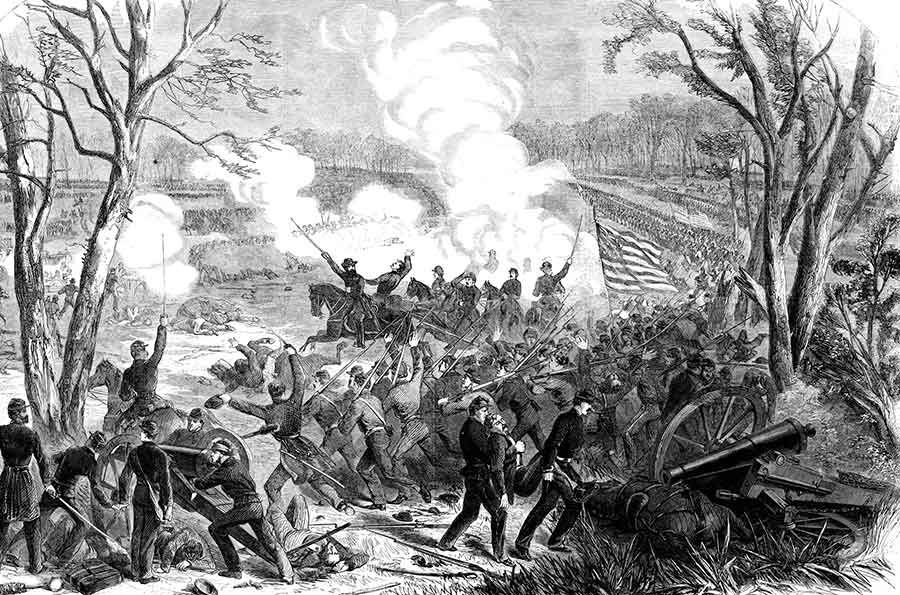

During the parley, a long line of Texans with skirmishers out front had worked their way up the gentle slope from bottomland east of the Mississippi Central tracks. They moved steadily over bare fields and through groves of evergreens and leafless oak trees to the top of the rise. A broad “open space intervened” in the face of Union strongpoints. It was “the prettiest line of battle in action I saw in the whole war,” wrote a Rebel observer. They opened fire as they came forward.

“The enemy advanced until I fired a musket,” Graves wrote, a reference to the signal upon which his men were to fire. What “seemed a living sheet of flame” to one Texan suddenly erupted from the well-concealed Union defenses. A “leaden hail” poured from the cotton platform breastwork beside the railroad embankment while rifle fire erupted from the fortified buildings in Middleburg, which overlooked the tracks. “Our men sunk away like stubble before a fire,” recalled a Texan.

After that first volley, “the enemy broke up in confusion,” recalled Graves, “and sought log buildings and ditches.” The shaken Rebels regrouped and began trading shots with the stubborn bluecoats. Noted a Union correspondent: “[T]he enemy tried several times to draw us out of our fortifications.”

Confederate storming parties scurried over the no man’s land in the face of destructive fire from troops ensconced in what one Southerner termed their “miniature forts.” Graves’ men repulsed each sortie in turn. “[W]e was whare thay couldent get at us,” a defender recalled, “[T]hay said that the yankeys craled in a hoal.”

At least one civilian was caught in the crossfire. William W. Casselberry, overseer on a local plantation, was in the store when the fighting suddenly erupted. With seven children at home, including a 1-year-old, the Christmas Eve morning sojourn to town may have been for gifts. During a lull in the battle, he was peering through a window when a gunshot shattered a pane. Glass shards flew in all directions, slightly wounding Casselberry. He spent the rest of the battle crouched in a hallway.

Gunshots also took a mounting toll on attackers. “[W]e were pushed forward,” grumbled one Lone Star Confederate, “without even knowing where or how the enemy was situated, or what their strength.” Another Confederate labeled the Middleburg assaults “useless and reckless.” One Unionist claimed several attackers “came in to surrender themselves as prisoners.”

The fusillade echoed in Middleburg for two hours before Van Dorn arrived from Bolivar with Jackson’s and McCulloch’s brigades. Fourteen hundred Yankee horse soldiers led by the aggressive Grierson were barking at their heels.

Without artillery to blast the feisty garrison out of Middleburg, Van Dorn decided it was time Griffith disengaged. “After losing many valuable lives, to no purpose,” a disgruntled Rebel wrote, “we proceeded on our retreat at a break-neck pace, the enemy’s cavalry moving to intercept us.”

Van Dorn intended to rejoin Pemberton’s army near Grenada, Miss. That night his command sped southward through Van Buren and camped a few miles below Saulsbury, near the Mississippi border and more than a dozen miles from Middleburg.

When darkness halted his pursuit of Van Dorn, the tenacious Grierson bivouacked at Saulsbury. From here, the colonel sent a dispatch to Grant: “I am camped within 2½ miles of the enemy. I…will follow them to their den.” Back in Middleburg an uneasy peace settled over town.

Graves reported losses from the Middleburg clash totaling six wounded, “1 since dead, and prisoners, 13.” The death, though, might have been accidental. In a letter home just days after the battle, Private James Ewing, Company G, revealed, “one of the Boys shot himself and dide.”

The 12th had lost sundry “camp equipage, &c…” including, “a valuable horse…[and] my overcoat, dress-coat, &c.” Graves reported. “But so far as I am concerned they are welcome to all…The enemy finally left us ‘monarchs of all we surveyed.’”

A reliable count of Confederate casualties wasn’t possible. Some of their dead were buried elsewhere, and they “carried off quite a number of their wounded.” Graves, though, was “satisfied in my own mind that the rebels loss, in killed, wounded, and prisoners, exceeds 100 men….Their loss would have been much greater had it not been for some half a dozen houses that afforded them shelter.”

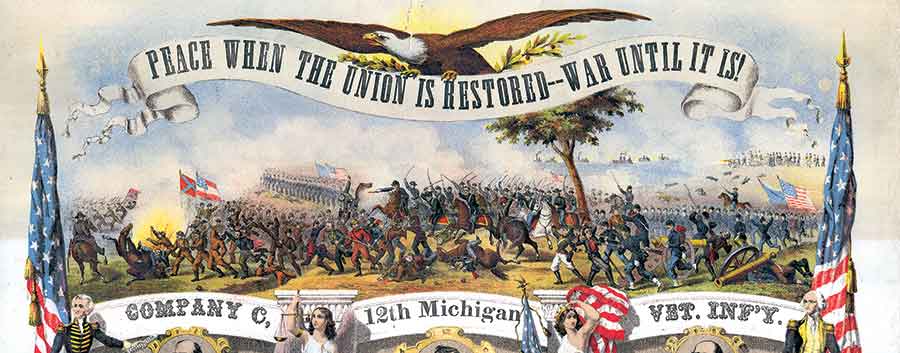

Grant praised “the gallant Twelfth Michigan” for its “heroic defense” of Middleburg against “an enemy many times their number.” The regiment, Grant boasted, was “entitled to inscribe….Middleburg, with the names of other battle-fields made victorious by their valor and discipline.”

And Mr. Casselberry? The story goes, “It was long after the last gun had been fired before he could be persuaded to get his mule and go home….[F]or days afterward, he was nervous whenever he looked out a window.” One may also imagine that for years to come the Casselberry children (eventually numbering 11) were regaled with chilling tales of their dad’s experiences during the fight before Christmas.

George Skoch, who writes from Fairview Park, Ohio, is co-author of the book Mine Run: A Campaign of Lost Opportunities–October 21, 1863–May 1, 1864.

Now You See It, Now You Don’t

Consult your GPS or a paper map today, and there it is: Middleburg, in Tennessee’s Hardeman County. Drive there via Tennessee Route 18 from either direction, however, and you’ll likely glide by not knowing a town ever existed there.

Today, what may be the lone holdover from the Civil War era is a decaying clapboard building first used to store cottonseed. For much of the last century, the building housed the Lax family store, but it now lies vacant along the highway near what had been the Mississippi Central Railroad (later Illinois Central) grade, also abandoned long ago.

First settled in 1825, Middleburg had a post office by 1827, and boasted a depot on the Mississippi Central by 1859. In 1860, Middleburg was incorporated, extending its limits generally southwest a mile or more from the current site. Though the railroad helped the local economy, it also made it a magnet for military action during the Civil War.

The fight before Christmas 1862 was actually the second time enemy forces met at Middleburg. The first came four months earlier, on August 30, when Colonel Mortimer D. Leggett’s Union cavalry and Colonel Frank C. Armstrong’s Confederates clashed “with great vigor and determination.” The heated eight-hour encounter included one of the war’s rare, saber-to-saber cavalry charges. In the 1940s, the Tennessee Historical Commission erected a roadside marker to that struggle. No marker exists for the December 1862 fight.

Decades after the Civil War, a story emerged that following Federal occupation, an “ardent sympathizer of the Southern cause (said to be a woman) sought to prevent the return of its bluecoats by setting fire to the town,” apparently inciting “bushwhackers to do the burning….[P]ractically all the business houses, the log schoolhouse, and most of the homes were totally destroyed.”

This might explain why nearly every trace of the wartime hamlet has vanished. But the tale is apocryphal. Available documentation, such as military reports and memoirs, paints a different picture. For example, the war diaries of 12th Michigan Privates Koon and Ewing, who remained in Middleburg on guard duty until their regiment left for Vicksburg on May 31, 1863, do not mention a fire of any kind in town.

Detailed accounts kept by a prominent Bolivar resident, John Houston Bills, do not support the story either. Throughout the war, Bills often traveled through Middleburg and commonly reported on depredations in the region committed by both North and South, including the sacking and burning of Bolivar in the first week of May 1864. But nowhere in his diary does Bills mention a conflagration in Middleburg.

Likely, the natural ravages of time and economic downturns took their toll on the community. The Middleburg post office was removed in 1915, and over the following decades rail service dwindled until it too ended entirely. According to one regional historian, “there was a general decline in all the towns in the area as a result of the war. Some towns survived at some level—some, such as the case of Middleburg, did not. Also, being between the town of Hickory Valley just to the south, and Bolivar to the north, most people in the area eventually gravitated to those two towns. Middleburg was ‘caught in the middle’ so to speak.” –G.S.