More than 70 years after the first Northrop YB-49 flying wing prototype took to the skies over Muroc Army Air Base in the Mojave Desert, the echoes of its jet engines still linger. Part of the airplane’s allure stems from its radical design and the tenacity of the brilliant engineer who conceived it. While the story of the short-lived YB-49 and its line of progenitors has been told before, some remarkable facts still emerge from the memory of a key participant in the flying wing program.

The last living pilot to test the flying wings in the late 1940s is retired U.S. Air Force Brig. Gen. Robert Cardenas, whose career in Army khaki and Air Force blue spanned 30 years after World War II. The 100-year-old Cardenas, best known as the project manager and B-29 pilot for the Bell X-1 supersonic program in 1947 (see “Dropping the Orange Beast,” ), still vividly recalls his experiences as chief test pilot for the XB-35 and YB-49 flying wings.

Born from the fertile mind of aeronautical engineer John “Jack” Northrop, the flying wing concept was based on the idea that a conventional airplane consisting of wings, fuselage and vertical and horizontal stabilizers was inherently inefficient. Most of its structure contributed nothing to lift but added greatly to parasitic drag. Northrop was determined to design and build a plane that eliminated every component that didn’t contribute to lift and forward thrust. Its structure would consist of one element: the wing. It was aeronautical design reduced to its purest form. It would mean greater fuel efficiency, simpler construction costs and time, and ultimately lead to a revolution in aviation.

By 1938, after a series of successes with other companies, Jack Northrop was ready to follow his dream. In 1940, while Hitler’s legions were running rampant across Europe, Northrop’s new company produced the first true flying wing, the N-1M “Jeep,” featuring a laminated wooden wing. But after more than two dozen flights over the dry lake beds near Rosamond, Calif., it was obvious the N-1M was too unstable on the vertical or yaw axis. In time, a series of more advanced experimental wings led to the successful N-9M, four of which were built. With twin pusher propellers driven by two six-cylinder Menasco engines, the N-9M flew at 200 knots with ease. Its 60-foot wing was a smoothly configured airfoil based on National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics specifications. The plane proved that a large, all-metal wing was not only feasible but an aeronautical inevitability.

Fears that Great Britain would fall to Nazi Germany led the U.S. Army Air Corps to consider a very-long-range heavy bomber that could fly from the continental United States to Germany and back. The specifications, issued in late 1940, called for an airplane with a range of 10,000 miles carrying five tons of bombs. As far as Northrop was concerned, those numbers were tailor-made for his flying wing. His design team went to work and by 1943 had demonstrated their concept to the Army Air Forces. Northrop came up with the radical idea of a combined elevator and aileron (elevon) for both longitudinal and lateral control.

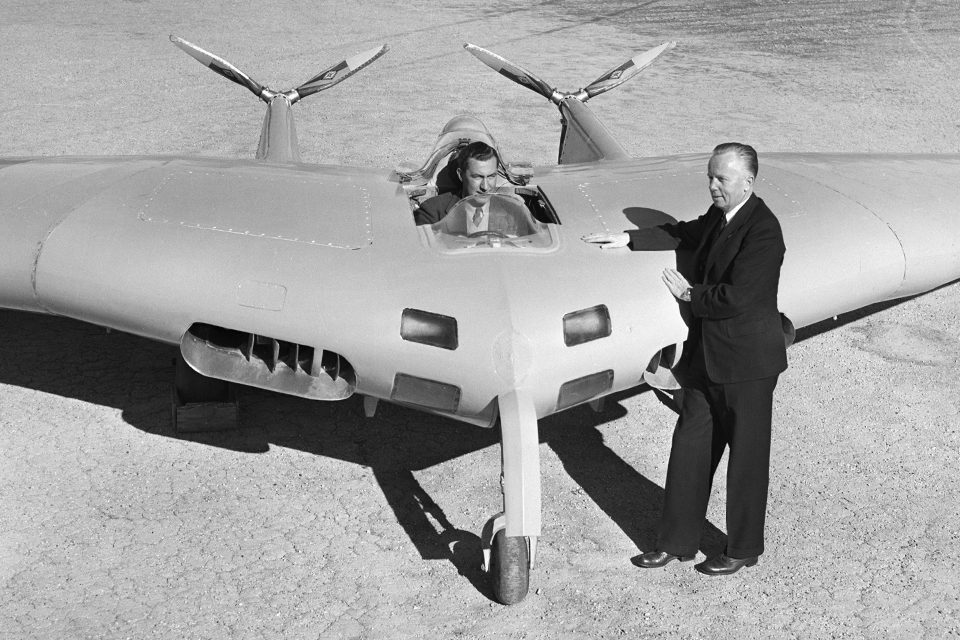

Northrop test pilot Max Stanley was at the controls when the XB-35 first lifted off from California’s Hawthorne Airport on June 25, 1946, and headed east toward Muroc. The plane flew like a dream as its four Pratt & Whitney radial engines drove contrarotating propellers that droned like a tsunami of angry bees. The XB-35 flew at more than 300 knots and had a potential range of 8,000 miles, very close to what the AAF wanted.

Problems with the flying wing’s control drive and contrarotating propellers soon led Northrop to switch to standard single props, reducing top speed and rate of climb. With the AAF already favoring the huge conventional Convair B-36 bomber, he needed to find a way to increase the XB-35’s performance.

In early 1947 Colonel Albert Boyd, head of the bomber test section at Wright Field in Ohio, sent Major Bob Cardenas to California to evaluate the XB-35 and other experimental aircraft. A highly skilled bomber pilot and engineer, Cardenas was the right man for the job. “Mister Northrop was very happy that I was on the team,” he said. “I really respected and liked him.”

After Stanley checked him out in the XB-35, Cardenas quickly developed some opinions about the flying wing. He was among the first to suggest switching to jet engines.

“I made one flight in it,” recalled Cardenas, “and in addition to my report, I said, ‘As to flight characteristics, you have good vertical stability on takeoff, but frankly speaking, it’s a dog. It needs more power for its size than the propellers can provide. If you put jets in it, it will improve its capability.’”

Cardenas’ opinion carried weight with Northrop. The eventual result was the YB-49, which utilized the same airframe but incorporated eight Allison J35 turbojets in the wing, four on each side. The first prototype’s maiden flight was on October 22, 1947, from Hawthorne to Muroc. The jet version performed well, and proved to be easier to fly than its propeller-driven predecessor.

Recommended for you

With a wingspan of 172 feet, the YB-49 was 30 feet wider than a B-29. The cockpit bubble was 15 feet off the ground. The crew was to consist of a pilot, copilot, bombardier, flight engineer and two gunners.

Cardenas began testing the new YB-49 in January 1948. “It was a beautiful plane, a lovely design,” he noted. After a series of taxiing tests he flew it with Major Daniel Forbes as copilot. He found that the switch to jet engines had created some undesirable characteristics. “They had not reckoned with the higher acceleration of the jets,” he explained. “It was slow at first, but then rapidly increased. The gear doors had not been modified and would not close fast enough to compensate for the faster airspeed. I had to pull up steeply to compensate.”

The early jet engines were prodigious fuel hogs, and the YB-49 consumed fuel so fast that its range was cut in half. Gone was any hope of competing with the long-range B-36 as an intercontinental bomber. But on April 26, 1948, Max Stanley set an unofficial endurance record in the YB-49, staying aloft for more than 9 hours, 6½ of which were above 40,000 feet. The flight was a triumph for Northrop, but his joy would be short-lived. The Air Force was not in the market for a medium-range bomber, no matter how advanced its design.

The YB-49 pilot’s position was in a bathtub-shaped compartment set dead center in the upper forward surface of the wing under a bubble canopy. The copilot was to the right and below, inside the actual hull of the wing’s leading edge. “Visibility was pretty good from the pilot’s seat,” noted Cardenas, “but the copilot could only see ahead and down, but not very well to the left.”

Each pilot had a control wheel that transmitted input to the elevons on the wing. Foot pedals had dual functions: They activated drag clamshells on either wingtip to act as rudders or were used in tandem as speed brakes. Despite the unusual arrangement, how the wheels and pedals controlled pitch, roll and yaw would have been familiar to any pilot. The throttle quadrant was set well above the flight controls.

The cramped and decidedly odd cockpit configuration was a reflection of the flying wing’s radical design and hasty development. The narrow, tube-like ingress from the aft ventral hatch meant that an emergency bailout would be nearly impossible.

Early in flight testing, Cardenas and Forbes faced a sudden emergency. “One of the first things you do on any new aircraft is to find out at what speed it stalls—that one certain point when the wing drops off and the nose drops down,” Cardenas explained. “We did our stall tests at 15,000 feet. Without any warning the nose quivered, went down, and it kept going and we ended up in a negative tumble.”

For Cardenas, the horizon suddenly rose sharply as the YB-49 pitched forward, tumbling “ass over teakettle.”

“My rear end was off the seat,” he recalled. “My arms were way up, but that was wonderful! The throttles were above me and I could reach them. I waited until the nose was level with the horizon and applied power to the right-side engines. I was hoping to ‘cartwheel’ the aircraft and from that it would turn into a spin. That’s how I recovered. Danny Forbes was with me. He saw how I recovered from that tumble.”

That May Cardenas was going to be married and attend the University of Southern California to pursue an advanced engineering degree. Asked by Boyd to appoint a replacement, he suggested his good friend Captain Glen Edwards. Edwards and Forbes began the next phase of the test program, which involved advanced stability and control tests. “Glen had helped to write the book on stability and control,” said Cardenas. “I felt he would be better for this phase of the testing.”

On June 5, 1948, Forbes was in the pilot’s seat of the second YB-49 with Edwards as copilot, along with three crew members. As they were flying high over the dry lake the flying wing went into another violent tumble, but this time evidently it was positive, not negative. The horizon before them suddenly dropped as the leading edge rose to point at the sky, then the wing fell back and pointed down. The big aircraft flipped over and over. But unlike the forward tumble in which Cardenas was lifted up by centrifugal forces, Forbes and Edwards were virtually glued to their seats. Neither would have been able to reach up those few precious inches to grab the throttle controls. As they fell, their airspeed increased past the point of control and the airframe overstressed outboard of the engine nacelles. The wing tore, snapping steel frames and folding the aluminum skin.

The YB-49 fell out of the sky like a brick and impacted on the desert floor. All five crew members were killed.

Boyd ordered Cardenas to take up the first YB-49, find out what had happened and finish the tests. “I was not directly involved in the crash investigation,” Cardenas said, “but I have some strong opinions as to what happened. I never read the final report on the crash. I was told to stay out of it.”

Cardenas is still in possession of a six-inch-long steel bar, U-shaped in cross-section and torn at one end. “This is a piece of the wing longeron,” he explained. “That’s where the wing folded.” Pointing at the twisted steel, he asserted, “It shows that the aerodynamic force was from a positive tumble.” To this day Cardenas’ voice still betrays emotion when discussing the crash that killed his friend and four others. “I envision Danny trying to reach for the throttles, trying to do what I had done. But he couldn’t do it.”

Cardenas reported his opinions to Northrop. The designer flatly informed him that a positive tumble was impossible. That was the first break in what had been an amicable relationship.

Northrop, for his part, was upset and depressed by the crash, but he still believed in his flying wing and refused to accept that there were any serious stability problems. Tests resumed, though certain realities were becoming apparent. The YB-49 proved to be an unstable bombing platform. A series of flights using a Norden bombsight revealed that it took a great deal of time and effort to stabilize the flying wing on a bomb run. The Air Force needed a bomber that could quickly line up on a target for an accurate strike. But the YB-49 remained prone to yaw instability. While the problem might eventually be corrected, by November 1948 the truth was evident to Cardenas, and by extension, the Air Force.

In a last-ditch effort to fix the stability problem, Northrop urged the Honeywell Corporation to modify the YB-49’s autopilot to help dampen yaw. While it did improve yaw stability, it didn’t solve the pitch instability that had been encountered with such disastrous results.

After writing his report to the Air Force, Cardenas summarized his opinions in a meeting with Northrop and his team. He was concise and frank, and backed up his conclusions with hard engineering facts. Most accounts say that Jack Northrop took it stoically, but in fact he was not ready to accept defeat. He had already received an order for 30 YRB-49 reconnaissance versions, to be fitted with six jet engines. While that was encouraging, Northrop was hoping for more. He wanted the flying wing to be the Air Force’s main strategic bomber. But in addition to Convair’s huge B-36, Boeing had developed the sleek medium-range B-47, a six-engine conventional subsonic jet bomber. Ultimately it would be the last nail in the flying wing’s coffin.

Then hope dawned in the form of a request from Secretary of the Air Force Stuart Symington and President Harry Truman to fly the remaining YB-49 from Muroc (soon to be renamed Edwards Air Force Base in Glen Edwards’ honor) to Andrews AFB in Washington, D.C. The president, well known for supporting the Air Force, wanted to be shown this remarkable piece of aviation technology.

On February 9, 1949, Cardenas and copilot Max Stanley flew nonstop from California to Washington in a record 4 hours and 5 minutes. At Andrews Truman climbed aboard, and Cardenas, who was still up in the cockpit, saw the gray-haired, bespectacled, grinning president emerge from the aft hatch. “I saw him looking around and being very impressed,” recalled Cardenas. “He said, ‘Major, this looks pretty good to me in spite of the horrible cockpit layout. I think I’ll buy some.’ I had already submitted my report that the plane was unstable and inherently dangerous, so I kept my mouth shut.”

Truman asked Air Force chief of staff General Hoyt Vandenberg to have “this young whippersnapper” fly the YB-49 down Pennsylvania Avenue at “rooftop” level. He wanted the people to see what he was buying for them.

Still shaking his head at the memory, Cardenas said, “I was told to do it. I was cruising down Pennsylvania Avenue at 200 knots and watching for radio towers when I saw the Capitol dome looming ahead of me. I pulled up and cleared it, but that was kind of hairy.” It would be the flying wing’s last moment of triumph.

In March 1950 disaster struck again when the first YB-49 crashed and burned during taxiing tests with test pilot Russ Schleeh at the controls. Although the accident did not result in any deaths, it was the last straw for the program. Despite the supreme efforts of the Northrop team, Secretary Symington had already decided to cancel the YB-49. The remaining XB-35s that were undergoing jet conversion were to be scrapped.

Jack Northrop was convinced that there had been a high-level conspiracy by Symington to stop the flying wing in favor of the Convair and Boeing bombers. But in truth its shortcomings were just too great to overcome given the technology of the time. With the Cold War looming and the Air Force needing good, reliable bombers, Northrop’s dream of a flying wing fleet was impractical. It was simply a bomber too far.

Frequent contributor Mark Carlson is the author of Flying on Film and The Marines’ Lost Squadron. Further reading: Northrop Flying Wings, by Peter E. Davies, and The Flying Wings of Jack Northrop and Northrop Flying Wings, both by Garry R. Pape.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2020 issue of Aviation History.