There is truth to the old adage “every tombstone tells a story.” Few do so as provocatively as Mayville, N.D., police officer Even Paulson’s headstone. For 129 years snow, ice, wind and moss have done their best to sully his grave marker in the town’s tidy cemetery, but not enough to obscure the gripping inscription:

EVEN PAULSON

Born Dec. 29, 1862

Killed while on duty

As Nightwatchman at

MAYVILLE, N.D.

Sept. 3, 1893

1 o’clock a.m.

To lay eyes on the chiseled epitaph is to feel the piercing depth of loss dealt to a close-knit community. It’s uncommon to find the cause of death on a tombstone. In this case those few words held the genesis of their aftermath: a community’s anger, the spectacle of a sensational trial played out in the media across five states and the repercussions that would reverberate for two decades.

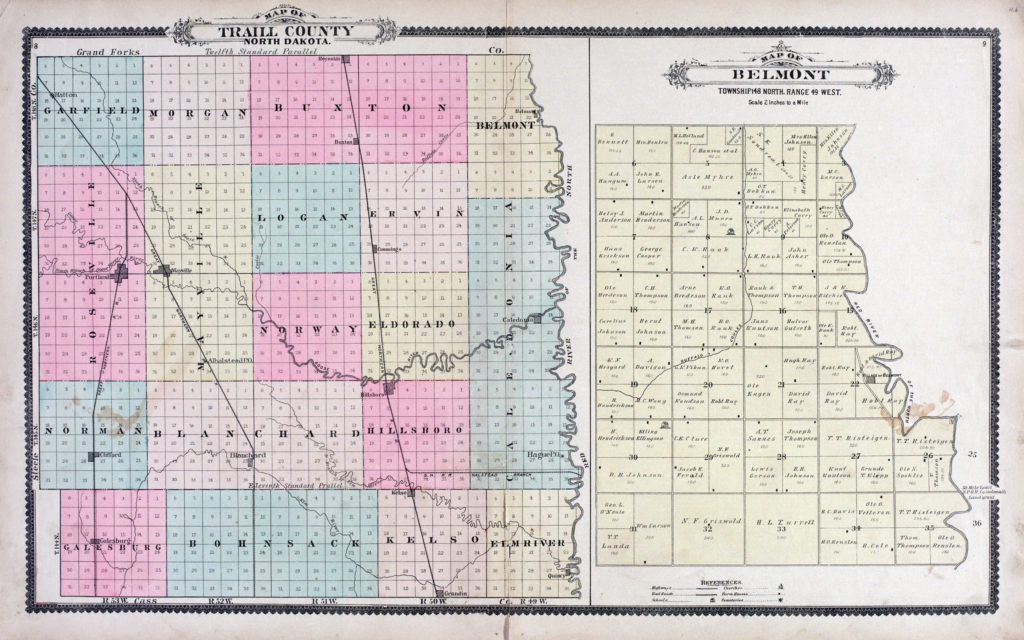

Paulson was 4,000 miles from his birthplace and just 30 years old when his life came to an abrupt and horrific end down a dark alley in small-town North Dakota. Born in Seljord, a village in Telemark, Norway, he was 21 years old when he took what was likely his last look at his homeland and his parents. Arriving in Quebec in 1884, he headed for Granite Falls, Minn., and within two years filed declaration of intention papers (a precursor to becoming an American citizen) in Yellow Medicine County. By 1892 he had made his way to Traill County, N.D., where on May 13 District Judge William B. McConnell granted him citizenship.

North Dakota’s 1889 entry into the Union as a prohibition state ensured there would be wild confrontations between bootleggers, speakeasy proprietors (aka “blind piggers”), the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and lawmen sworn to uphold the state constitution, regardless of their own attitudes about alcohol. But Officer Paulson was universally trusted and immensely liked in Mayville, even by those he arrested. “His personality was so engaging,” writes Harold Wenaas in his 1996 book Stener: The Sheriff From Telemark, “he could talk unruly toughs and drunks into voluntarily accompanying him to the city jail.” (The author’s grandfather, Stener Wenaas, served as a deputy sheriff and sheriff of Traill County and hailed from the same small Norwegian town as Paulson.) Paulson believed policemen should be visible in their communities, thus he became a fixture on the streets of Mayville, talking to children, parents and business owners.

But a crime to which there were no eyewitnesses except the victim’s dog can only be retold second- or thirdhand, so the story of Paulson’s murder must be pieced together through the public record and from numerous newspaper accounts, splashed across front pages from Iowa to Minnesota, including at least two Norwegian-language papers.

The Crime

The Most Atrocious Crime in Traill County’s History

So declared the headline in the Hillsboro Banner. It all came down to booze. Shortly before 1 a.m. on Sept. 3, 1893, Officer Paulson had surprised burglars in the act of stealing liquor to bootleg from a warehouse behind the R.L. Kenney & Co. drugstore, whose pharmacist used alcohol in the preparation of medicines. The first shot, to the abdomen, dropped Paulson. His shouts for help carried on the night air until silenced by a second bullet, to his forehead at point-blank range. When all fell silent, Paulson’s dog remained beside the body of his fallen owner.

The killers promptly bolted, each in opposite directions. Moments later a thump against a nearby home alerted its resident, who saw a man disappear over a fence. A posse described in Wenaas’ book as “half the population of Mayville” pulled one James Kelly, either drunk or claiming to be, from the crawlspace beneath the train depot and hauled him to the city jail. The next morning authorities discovered the source of the thump in the night—a .44-caliber Winchester rifle traced to local butcher William Law. A search of Law’s room turned up the stolen goods in a trunk. The price of Paulson’s life—a 10-gallon cask of port wine. He’d been shot when the burglars returned in search of whiskey.

An enraged mob of 700 choked the streets. Describing the crime as “one of most unusual cruelty,” the Hillsboro Banner reported, “It was with greatest difficulty that lynching was prevented.” Cooler heads managed to quell the fury long enough for County Sheriff William K. Seaver to hold both prisoners (“two well-known town toughs,” according to the Hope Pioneer) for a day before transporting them across the line to the Cass County Jail, in Fargo, to await trial during the next term of court at Hillsboro, the Traill County seat.

One might wonder whether Law and Kelly witnessed the funeral procession for Paulson, a solemn line of horse-drawn carriages that extended a mile. The Reverends George Curtiss and Jens Lonne spoke in English and Norwegian, respectively, to the largest funeral gathering Mayville had ever witnessed.

A 28-year-old Maryland native, Law had made his way to North Dakota only a few months earlier. While working as a butcher in Fargo, he’d fallen in with undesirable company and left for the smaller town of Mayville.

Kelly’s appearance suggested a rough path in life. Barely 30 years old, he was already graying and balding, with a crooked nose and a left eye noticeably larger than the right. A Massachusetts-born transient laborer, he lived in a camp just outside town and sometimes assisted butcher Law, slaughtering stock with the latter’s Winchester in exchange for cuts of meat.

Neither man denied the robbery. Both denied the murder. Law and Kelly claimed they had a third accomplice, referred to only as Murphy, whom they claimed fired the shots that killed Paulson. Despite an all-out search and a proffered reward, however, no third man ever turned up. Jim Davis, head of reference at the State Archives and Historical Research Library in Bismarck at the time this article was researched, was likewise unable to find any credible reference to a third party. “I doubt there ever was one,” he said. “In cases like this there’s always a ‘third party’ brought up as the actual person who did the killing, and there’s no one who can really dispute it.” Was there a faceless third man who got away with murder? Only Kelly, Law and Paulson know.

A grand jury in Hillsboro returned four indictments, two each for murder and burglary. Kelly suffered a “severe hemorrhage of the lungs” while awaiting trial in the Cass County jail but survived to face his day in court.

The Trials

As the trial dates for Kelly and Law approached, the Grand Forks Herald questioned little Hillsboro’s ability to handle the expected crush of trial watchers and urged the Great Northern Railway to offer fare inducements that would encourage people to stay in Fargo or Grand Forks. “The trial of the supposed murderers will be closely watched and the outcome of which may prove beneficial or otherwise,” the paper wrote. “A prospectus for North Dakota regarding labor for the coming year may hinge, regarding morality, on this very case.”

A request by defense attorney Francis W. Ames (later a state senator and reporter of the North Dakota Supreme Court) for a change of venue was denied. On Jan. 20, 1894, a trial jury was empaneled and a slate of 20 witnesses submitted for examination. “Although this dastardly deed has been commented on and hashed over and over again in the hotels, business places, clubs and at the homes, and opinions freely expressed,” the Herald reported, “a jury has been drawn that has not expressed themselves, but will when the proper time arrives.”

Kelly’s confession to the coroner’s inquest formed the centerpiece of his trial. He admitted to the robbery, implicated Law and the alleged third party, and claimed he wasn’t even present for the murder. Placed on the stand, he denied the coroner’s evidence and, in doing so, contradicted himself. The jury deliberated through the night before returning a verdict of guilty on January 29. “The law of this state allows the jury to fix the penalty,” The Dickinson Press wrote in its coverage of the sentencing. “They say imprisonment for life. The evidence is all circumstantial, but the public sentiment says guilty.”

Traill County State’s Attorney John Carmody (a future state Supreme Court justice) painted Law as the principal in the crime during his trial. On February 1 Carmody, the Bismarck Tribune reported, produced evidence showing Law had “threatened some days previous to the murder to blow Paulson’s brains out and produced the gun and said that gun would do it.”

“That gun” was the Winchester. On February 9, after another overnight deliberation, the jury voted to convict.

Lack of definitive proof as to who pulled the trigger also spared Law the gallows. He, too, was sentenced to life imprisonment at the North Dakota State Penitentiary in Bismarck. Judge McConnell, who nearly two years earlier signed the papers granting Paulson his American citizenship, pronounced sentence on the pair. “Did you hope that the jury might waver in their duty and extend an avenue of escape through sympathy for you?” he boomed. “If so, stop and consider whether or not you showed to Even Paulson any sympathy or mercy. Did you stop to consider that he was an honorable citizen, a faithful officer and in the performance of his duty? Did you consider his father and mother in Norway and his sisters here and how your act must so cruelly wound the love and affection they had for this son and brother? It is indeed a sad spectacle to see one of your years receive the sentence of banishment for life, from all the objects, hopes, anticipations and pleasures of life, and to think you merit such a desperate penalty.” Law and Kelly were delivered to the state penitentiary on February 13, duly described by the Bismarck Weekly Tribune as “evil-looking villains, whose faces were made to grace a rogue’s gallery or adorn the space behind prison bars.”

Paulson’s life had come to its end, as had the trials of his convicted murderers, but the story didn’t end there. Little more than two years later, on May 11, 1896, the Bismarck Tribune reported: “A movement is afoot to get a new trial for Lowe [sic].…K.P.’s [Knights of Pythias, to which Law belonged] are said to be interested.” Traill County’s collective temperature blew sky high in May 1899 on word that Governor Frederick B. Fancher would hear Law’s application for pardon. “They had their trial,” stormed the Hillsboro Banner, and their life sentence “was considered lenient for such red-handed murderers.” Law’s family and the Knights of Pythias pressed hard for his release. Mayville’s mayor unleashed strongly worded protests signed by “everybody” in Mayville and Hillsboro. After deliberating several weeks, Governor Fancher denied the petition, declaring himself “unable to sufficient cause why I, as executive of this state, should interfere with the decision of the court.” But the efforts to free Law forged on unabated.

The Aftermath

What Kind of Man Is This Man McConnell?

So asked the Mayville Tribune in a banner headline on Sept. 12, 1901. Palpable outrage saturated Mayville and Hillsboro when McConnell, the judge who had presided over the trials of Paulson’s killers, but who no longer lived in North Dakota, signed a petition seeking Law’s release. The Tribune reprinted the text of McConnell’s 1894 pronouncement of sentence, tersely concluding, “Comment is unnecessary.” The Hillsboro Banner applauded the Tribune for “dishing up a rich brown roast for ex-Judge McConnell” and urged citizens to “read it, it will do you good and help to counteract any tendency towards that morbid sentimentality which is all too common in favor of jailbirds.”

The Knights of Pythias continued its widely reported efforts, and that December 21, against sustained, strenuous resistance by the citizens of Mayville, the state Board of Pardons commuted Law’s sentence from life imprisonment to 15 years. Traill County coroner Thomas Harrison released a statement blasting the board’s decision:

“While there remains not a shadow of a doubt that Law was the arch criminal of the two, his sentence has been commuted, while Kelly, who is friendless and unknown, is still condemned to end his days in a felon’s cell. If murderers are to be pardoned because they have fraternal friends who persistently press the matter…the wisdom of the law creating the [pardon] board must be doubted.”

Law walked free in 1907, having served little more than 13 years. Marrying shortly after his release, he ultimately settled in Minneapolis and resumed work in the meat industry. He died in 1945, leaving nothing to suggest anything other than an unremarkable post-prison life.

In December 1911 the Board of Pardons commuted the sentence of Kelly from life to 26 years, provoking the unforgiving Mayville Tribune to scathingly suggest he “join Mr. Lowe [sic] in Minneapolis and talk over old times.” Taylor Crum, the Fargo attorney who made application for Kelly’s release, presented the situation in a more benign light. Through discussions with the warden Crum had concluded Kelly might be useful as a handyman, perhaps at a hospital, and approached a local doctor on the convict’s behalf. “Unless arrangements can be made for employment,” Crum wrote the doctor, “at his age and after his long term of service, he might almost be better off to stay where he is than be sent adrift among the hobos of the Northwest.” Lifers almost always make good if allowed to stay in the local community, own up to their past and “start in right,” the attorney argued. “It would be much better for the old man than to be sent adrift looking for jobs in railroad and lumber camps…until he is invariably recognized and kicked from pillar to post. Don’t you agree?”

Kelly was released from prison in May 1912. His fate remains unknown, so for now the story ends here.

But it remains so much more than the story of an impulsive murder in the often violent and unpredictable Old West. Three young men from origins thousands of miles apart converged in the wrong place at exactly the wrong time, a coincidence of tragic proportions for all three. It speaks to the fragility of any random moment wherein lives are irreparably altered and history is written, immortalizing both the good and the bad that can live on after that random moment.

Oregon resident Ellen Notbohm is the author of The River by Starlight, which won a 2019 Spur Award for best first novel from Western Writers of America. This article on the Paulson murder is expanded from “A Tombstone Tells Its Story,” published in the July/August 2009 issue of Ancestry. After happening on Paulson’s grave marker and deciding to tell his story, Notbohm says, “More than a dozen researchers and organizations took an interest and dug deep for information, because, as Harold Wenaas tells us in his book Stener: The Sheriff From Telemark, ‘There was something special about Even Paulson.’”