Ruling like a king—and hardly a constitutional monarchy—from Fort Union, in what would become North Dakota, Kenneth McKenzie controlled the fur and buffalo robe trade along the upper Missouri River and retired with $50,000 to his credit after sanctions over his illegal sale of liquor to the American Indians cut into his profits. But frontiersmen remembered him for his somewhat eccentric approach to justice.

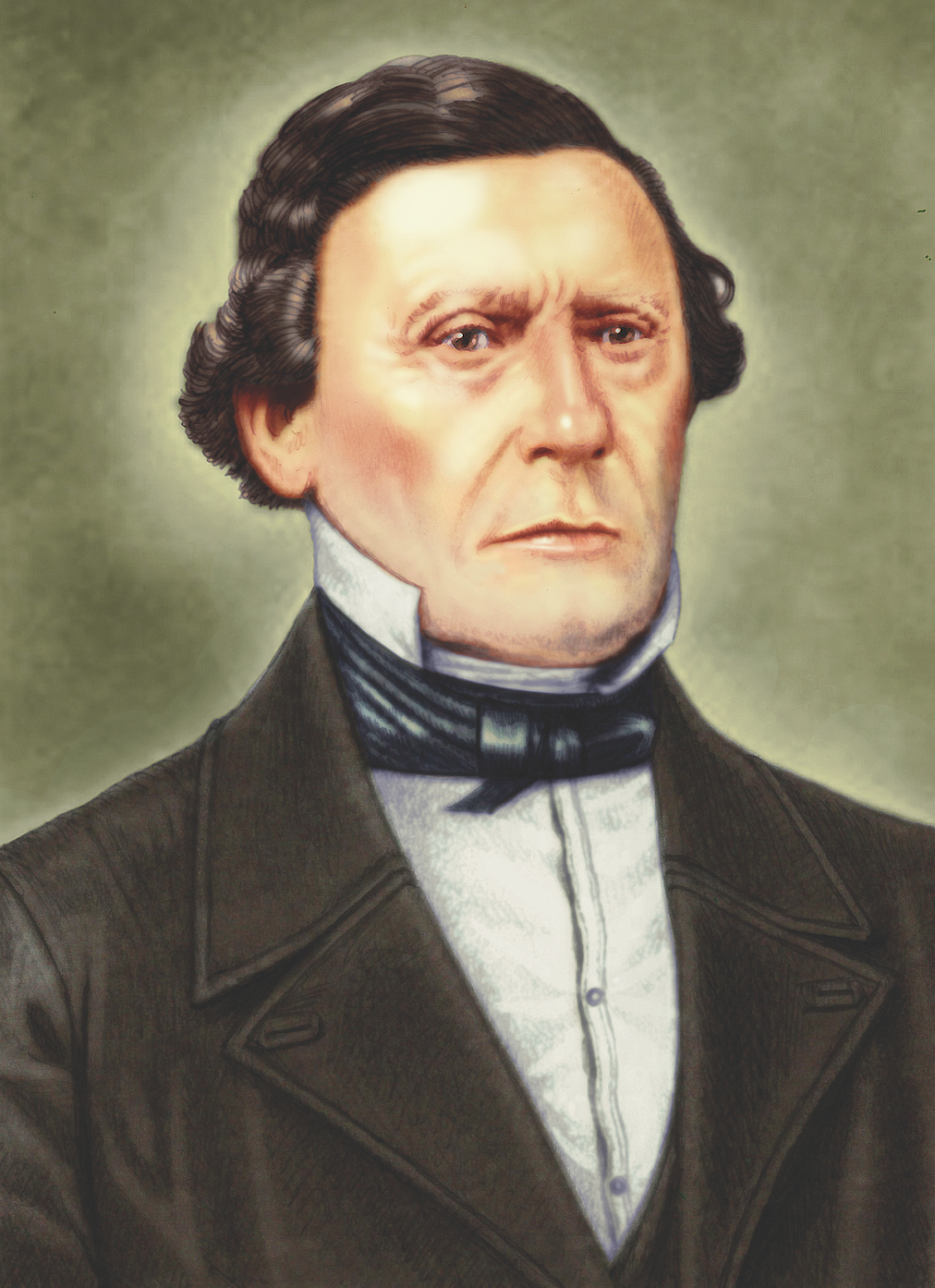

Born in Scotland on April 15, 1797, McKenzie had immigrated to the Americas in 1816, first to Canada and then to the United States. He learned the fur trade as a clerk before forming the Columbia Fur Co., which in 1827 merged into German-born John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Co. Taking the helm of American Fur’s Upper Missouri Outfit, the pugnacious McKenzie profited mightily from the operation of an illegal distillery at Fort Union, ultimately shut down by order of the federal government.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

His American Indian customers remained loyal mostly because the trader didn’t doctor his spirits with an inordinate amount of tobacco, pepper, molasses or water. Even after he resorted to smuggling, his product remained mostly whiskey. McKenzie also had enough authority to keep his white and half-blood employees from slaughtering one another in feuds that would have shocked Sir Walter Scott or William Shakespeare. He ruled his domain with all the conceit of Pecos Justice of the Peace Roy Bean a half-century later.

UNWELCOME RIVAL

Charles Larpenteur, a French-born trader, clerk and interpreter, recalled one particularly self-serving 1836 incident while he was working for McKenzie at Fort Union—an admittedly extreme case of personal justice or injustice, depending on one’s perspective:

“A certain free trapper named Augustin Bourbonnais came down the Missouri in a canoe.…He had been lucky on his hunt and had about a pack of beaver pelts, worth something like $500, which made him feel rich and quite able to pass a pleasant winter. Bourbonnais was only about 20 years of age, a very handsome fellow, and one thing in his favor was his long yellow hair, so much admitted by the female sex of this country.

This they call pah-ha-zee-zee, and one who is so adorned is sure to please them. A few days before his arrival Mr. McKenzie, who was nearly 50 years old and perhaps thought it was too cold to sleep alone in the winter, had taken to himself a pretty young bedfellow. Mr. Bourbonnais had not been long in the fort before he went shopping and very soon was seen strolling about the fort in a fine suit of clothes, as large as life, with his long pah-ha-zee-zee hanging down over his shoulders.”

AN INDECENT PROPOSAL

Wasting no time, Bourbonnais asked McKenzie’s pretty young bedfellow if she might like to change beds, and she expressed interest. McKenzie began to flaunt a large cudgel.

Larpenteur picked up the story:

“It happened one evening that Bourbonnais, encouraged by favorable returns of affection, went so far as to enter the apartments reserved for Mr. McKenzie. The latter, having heard some noises which he thought he ought not to have heard, rushed in upon the lovers and made such a display of his sprig of a shillelagh that Mr. Bourbonnais incontinently found his way not only out of the bedroom but also out of the fort, with Mr. McKenzie after him. It was amusing to see the genteel Mr. Bourbonnais, in his fine suit of broadcloth, with the tail of his surtout stretched horizontally to its full extent; but unfortunately for the poor fellow, he would not let the affair end in that way and swore vengeance.…

Sure enough, he was seen the next morning dressed again in buckskin, with his rifle on his shoulder and pistol on his belt, defying Mr. McKenzie to come out of the fort and swearing that he would kill him if he had to remain on the watch for him all winter. Still thinking that such performances would not last long, Mr. McKenzie preferred to remain a day or so in the fort, rather than have any further disturbance. But Bourbonnais kept up his guard longer than Mr. McKenzie felt like remaining a prisoner in his besieged fort.”

GETTING VENGEANCE

McKenzie first turned to the fort’s clerks for a solution. The clerks decided to ask Bourbonnais to leave quietly or face the consequences. Bourbonnais refused to go away. Larpenteur continued:

“A mulatto named John Brazo—a man of strong nerves and a brave fellow, who had on several occasions been employed to flog men at the flagstaff—was sent for and asked if he had nerve enough to shoot Bourbonnais, in case he should be desired to do so.…

‘Yes, sir—plenty!’

‘Well, will you do it?’

‘Yes, sir; I am ready at any time.’

John was then ordered to take his rifle into one of the bastions and shoot when he got the chance. John, as good as his word, took his position. I recollect that it was early one Sunday morning, a little before sunrise, when Brazo came to my room, saying, ‘Mr. Larpenteur, I have shot Bourbonnais.’”

Emerging from the post, Larpenteur and E.T. Dening, the bookkeeper and acting surgeon, found the wounded Bourbonnais, shot clean through but not dying. That spring, having more or less recovered—and wisely steered clear of McKenzie—he drifted downstream in his canoe.

After a long absence McKenzie himself returned to Fort Union, and things simmered down. Some years later a frontier ruffian named Malcolm Clark killed Owen McKenzie, Kenneth’s half-blood son. In his defense Clark claimed the younger McKenzie was drunk and dangerous, so he had cured Owen’s condition by putting three pistols balls through him. The shooter was a hardened veteran of the Texas Revolution, and this time there was no retribution.

Years after the government forced him to close his distillery and fall back on smuggled hooch, Kenneth McKenzie sought to regain control of the wholesale liquor trade. But he continued to spend more than he earned, and his plans came to naught. Later in life he married, raised children, farmed, invested in land and made money, though never as much as when he was “King of the Missouri.” The fur baron turned farmer died in St. Louis at 64 on April 26, 1861.

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 print edition of Wild West magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.