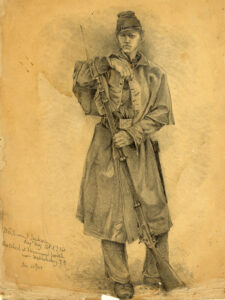

Determined Unionists used every means available to dodge the Confederate draft.

In February 1865, Mrs. Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick wrote an account of two Unionists from Randolph County, N.C., who decamped from Confederate ranks to the Union Army. Soon after proving their loyalty to the United States, they were released by military authorities from Point Lookout, a large Federal prisoner of war camp in Maryland. The story throws light upon how the outliers in the Quaker Belt survived:

These men lay [out] 18 and 21 consecutive months and had been occasionally in the woods for two and three months at a time before but at this [time—summer 1864] the conscripting became more cruel so that it was not safe to be at home at all. Sometimes especially during harvest they would come in and work in squads but always with their muskets within twenty rods and with the women and children stationed around to give the alarm if an unknown person or persons approached….They [the outliers] forbade shooting in general in the neighborhood of their camps lest it might lead to discovery. They dug themselves houses underground [in] the side of the hill with a trap-door covered with sticks brush and leaves and looking exactly like the face of the land around it. In this but little fire was needed to keep warm and much of the time none at all. Their food was usually cooked at home, excepting wild game, and brought to certain places at certain times. Signals[—]sometimes a whistle, sometimes a shout[—]were used to give notice of apprehended danger. When driven far from their homes as occasionally happened, as once they were ten miles, they always found those who would befriend them. They have a secret society formed for mutual protection [the Heroes of America] for all lovers of law and order and there signs are so plain that though entire strangers it is sufficient to gain protection and food so far as possible.

One of the intriguing aspects of outlier life in the Piedmont area was the extensive use of underground caves as mentioned in the story above, a technique long used by runaway slaves in the area to conceal themselves. Without the caves, the outliers would not have survived as well as they did. It is ironic indeed that Confederate draft-dodgers and deserters adopted the idea of building and hiding in dug-out caves from practices devised by runaway slaves to elude capture and live free.

The classic exposition of how outliers used caves to elude the hunters is David Dodge’s 1891 essay “Cave-Dwellers of the Confederacy.” Dodge detailed the criteria used in selecting cave sites and explained how the outliers constructed their hideouts. Were a cave site judiciously selected and the cave properly built, about the only chance the authorities had of finding it was to inadvertently step onto its roof and fall into it, which, of course, was a misfortune for hunter and cave dweller alike.

The outliers used the caves only in case of emergency, and thus they remained unoccupied most of the time. The outliers needed the caves only during daylight hours. At night, they rendezvoused with some family member to get food and other necessities, or, if surveillance were intense, they picked up food family members secretly deposited at some prearranged location, as mentioned in the Hedrick account.

Hedrick noted that accomplices used signals such as whistles or shouts to give the outliers warning of approaching danger. Dodge added that different colored or patterned bed quilts hung out on the clothesline constituted a system of signals between family and outlier. In addition, different songs and even hog calls formed a part of their secret repertoire. Indicating that some areas had elaborate neighborhood warning systems, abolitionist Guilford County farmer Jesse Wheeler wrote: “When soldiers are sent to hunt conscripts the blast from trumpet[s] will set an underground telegraph in operation by which information necessary was imparted to all parties concerned in short order.”

Though correspondents only rarely mentioned caves, there can be little doubt as to their extensive use in the Quaker Belt, and especially in the Randolph area, as suggested by the Hedrick story. For example, Gov. Zebulon Vance was informed by a Randolph County resident of the existence of caves in the Brower’s Mills community, as follows: “6 caves perhaps not more than 3 miles apart[,] 1 near Browers[,] 1 near Black and moons[,] 1 near Palmers etc. about 20 men in a cave.” A letter from a citizen of the Good Springs community in Moore County suggested that the hunters, in order to locate them, burned over wooded areas suspected of containing caves.

The Underground Railroad

Militant Unionists used the prewar “under- ground railroad” that area antislavery activists established to spirit runaway slaves northward to clandestinely transport outliers and others seeking to fee the Confederacy to the Federal lines. As in the case of the caves, there is considerable irony that deserters and delinquent conscripts feeing from the Confederate army benefited from a system originally designed to assist runaway slaves. The case of John Carter, superintendent of the New Garden Boarding School (a Quaker institution in Guilford County), provides a good example of the Underground Railroad activity that occurred in the Quaker Belt during the war. Carter “labored incessantly to keep young men out of the Confederate army by either concealing them, or passing them north via the ‘Underground R.R.’ ” Because of the demands placed on him by this activity, “there was often a week at a time that I did not take my clothes off to go to bed.” Jesse Wheeler provided further evidence of Underground Railroad operations between the Tar Heel State and the North. In November 1862, in a reference to the North Carolina refugees then arriving in Indiana, he wrote: “They say that there is a perfect underground rail road through the mountains of Kentucky by which hundreds escape.”

An account of the escape of a Captain Hock of the 12th New York Cavalry from the Salisbury prisoner of war camp in 1864 contains vivid testimony of the existence of the Underground Railroad and cave dwelling in the Tar Heel State. Upon escaping the prison confines, Hock found in North Carolina an underground railway, as systematic and as well arranged as that which existed in Ohio before the war. From the time that Captain Hock by accident, happened upon one of the stations of this road, his sufferings and trouble were, in large measure, over. He found food and resting places, stations in secure spots, guides over intricate mountain paths and a hostility to rebellion which the north, bitter as it was, hardly knew. Sometimes he would spend the night at the house of a prosperous farmer, sometimes in a cave with two or three young fellows who were seeking to baffle conscripting parties, and sometimes alone in the forest. But wherever he was, he was sure to find either explicit and unmistakable directions for the next stage, or a conductor, alert, active and cautious, who accompanied him over the more dangerous part of his way. Nor was this help withdrawn until from a mountain peak near the Tennessee border he was shown the federal fag floating over an outpost of our army.

Conductors instructed escapees from the Salisbury prison to follow the Yadkin River (which fowed a few miles northeast of the prison) north to Wilkes County, where militant Unionist pilots would guide them across the mountains to the Union lines.

There can be little doubt that hundreds—probably thousands—of North Carolinians, many from the Quaker Belt, fed north, especially to Indiana. In January 1862, Jesse Wheeler wrote from Dublin, Ind.: “Some hundreds of Carolineans have arrived in Indiana and hundreds of others are serious to come when opportunity offers. In this section [Wayne County] of Indiana the Carolineans and their descendents preponderate over the emigrants from…other States…and in nine cases out of ten are anti slavery [and] out and out firm supporters of the Administration [Lincoln’s].” The exodus of Unionists from the Quaker Belt to the United States continued unabated until the end of 1864. Writing from Spring Town, Ind., Wheeler reported in December 1863 that “a number of N.C. refugees reached Indiana this fall. I have knowledge of over forty from Guilford and Randolph[.] Some of them had been on the road nearly a year.” In May 1864, he noted that many refugees and deserters had recently arrived from Guilford, Alamance, Randolph, Chatham and Forsyth counties.

Reflecting the reaction of the Unionists and outliers to the February 1864 conscription act, which enrolled all able-bodied men between the ages of 17 and 50 into Confederate military service, and that summer’s deserter hunt, Wheeler noted that in November “the number of refugees from North Carolina who have arrived in Indiana is much larger this season than at any other period since the commencement of the war. Over a hundred have arrived in this month mostly from Guilford, Forsyth and Davidson, more than five hundred have escaped from Guilford and the counties adjoining since the 1st of march last mostly young men to escape being drafted and forced into the rebel army.”

Wheeler contended that, according to reports, Guilford County had almost one thousand outliers consisting of draft-dodgers, deserters and “escaped Yankee prisoners.” Indicating that the notoriety of the lower Randolph border area reached far and wide, he wrote: “The counties of Randolph, Moore and Montgomery are all famous for outliers, and it is said very few are captured through that portion of the State and that any [that] are captured…mostly get away or are released by their friends before they get to any military post.”

Correspondence of local citizens provides a few references to Randolph area people fleeing the state. For example, one correspondent noted: “Linday Leonard says he was 15 miles from the Yankee line and going to the Yankes as fast as he could get there, he says they will not be mealy mouthed about it any longer.” An excellent example is Jesse A. Miller, a deserter from Randolph County. Miller, a member of the Heroes of America [a secret, pro-Union underground organization], wrote a letter on November 15 in which he announced that he had made the decision that hundreds of other citizens in the Quaker Belt had made during the war—to go to the “Yanks”: “I have tried camp life [i.e., the army] a little and i dont like it at tall and I am on my way to the other side….I want you to come as Soon as you can if I get threw Safe and the Prosket [prospect] is good tell all the folks good by and right to Jo that I am gon to the Yanks and tell him goodby and all the rest I dont Never expect to see any of you any more good by to all….Mother says Shee is bound to go in thee Spring if Not Before to the yankes it is only a Bout 100 Miles [to] the Nearist place in the Mountains.”

Militant Unionists unfortunate enough to be drafted or captured and forced into the ranks often decamped to the Union side at the first opportunity. Others, captured in combat before a favorable situation to desert arose, found themselves inmates in Federal prisoner of war camps. Many, with the aid of sponsors who would vouch for their Unionist sentiments, took the oath of allegiance and went to live with relatives in Indiana or some other Northern state. Thus capture, as well as decamping and the Underground Railroad, provided the militant Unionist with a ticket out of the Confederacy to the United States.

Black heroes

There is some evidence that blacks, free and slave, cooperated with white militant Unionists in the operation of the Underground Railroad and in the anti-Confederate cause in general. A slave ferried Bryan Tyson across a river in eastern North Carolina to the Federal lines in 1863 during his escape to the North, and a slave assisted Federal Army Private Burson in his escape from the Confederate prisoner of war camp at Florence, S.C., to the Quaker settlements in central North Carolina. George Clark, a free black carpenter living in Davidson County and a member of the Heroes of America, served as a Unionist pilot to help guide Union Gen. George Stoneman’s cavalry when it invaded the western and central parts of the state in April 1865. Near the end of the war, a loyal Confederate from Randolph County informed Vance, “Our negroes are nearly all in league with the deserters.” In 1864, Vance was warned by another loyal Confederate that the deserters in Chatham County “intend arming the slaves.” The same year, authorities arrested a “free woman of color” in Montgomery County for “aiding deserters, etc.” A year earlier, a Confederate soldier, writing to his sister in Randolph County, speculated, “more than two thirds of those ‘slaves’ around Father’s are tories. I talked very plain to them and told them I wished the last tory was hung sixty thousand feet high!”

Unable to obtain large numbers of Confederate troops to assist his intimidated and weak militia force, Vance had to sit by in the summer of l863 and watch as deserters gathered into armed bands in the Quaker Belt and defied his militia officers, magistrates and sheriffs. Because of their clever system of communications and concealment, the deserter bands controlled the countryside in most of the Quaker Belt. Only when large numbers of Confederate and state troops were in their communities was their power seriously challenged. But as soon as the troops left, they resumed control of their areas. By July, the deserters and draft-dodgers roamed at will throughout the Quaker Belt, the authorities either unwilling or unable to stop them. That set the stage for the next act in the drama of the inner civil war: the insurrection of deserters, draft-dodgers and militant Unionists in conjunction with the movement for reunion and peace that swept the political scene in North Carolina in the summer and fall of 1863.

Adapted from Civil War in the North Carolina Quaker Belt: The Confederate Campaign Against Peace Agitators, Deserters and Draft Dodgers ©2014 William T. Auman by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. www. mcfarlandpub.com.

Originally published in the July 2014 issue of America’s Civil War. To subscribe, click here.