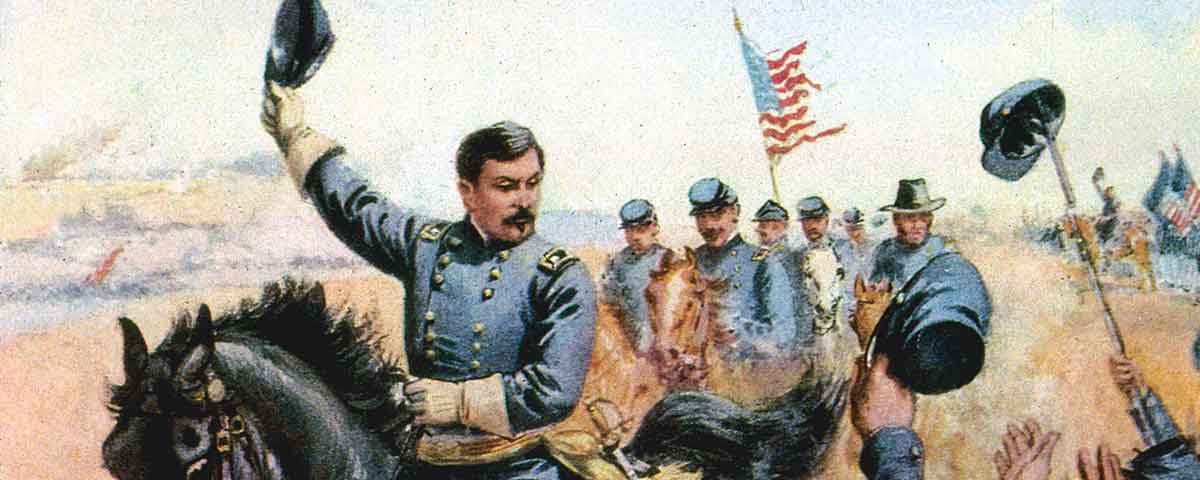

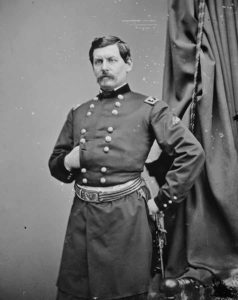

We love to bash McClellan, the Union Army’s calculating and cautious, contentious and contemptible, conceited and controversial general. You’ll find few Civil War historians or buffs willing to defend or stand with “Little Mac.” In many ways, McClellan deserves this censure. Criticisms levied against him include continual exaggeration of enemy strength; incessant demand for reinforcements to neutralize his opponent’s imaginary numbers; operational paralysis due to methodical preparation and ad infinitum planning; slow and deliberate movement—if movement at all; excessive caution and abhorrence of risk; and obsession with perfection—a precise condition that is impossible, of course, to attain.

The Civil War community has judged the general and passed its verdict on these charges: guilty on all counts. The sentence: permanent abhorrence of all matters McClellan. This excludes, by the way, indicting McClellan for his egregious character flaws, such as insolence, irritability, and occasional insubordination.

Then how do we explain that George McClellan defeated Robert E. Lee, the Civil War’s most beloved general?

Make no mistake. The Battle of Antietam was a disastrous loss for Lee and the South. The popular myth that the battle was a “draw” deserves debunking. Lee, indeed, escaped destruction. But why do we elevate that outcome to triumph?

Little Mac thwarted every strategic objective Lee intended to accomplish during his army’s first invasion of the North in September 1862. Lee failed to draw the war into Pennsylvania. Lee failed to threaten any major Northern city. Lee failed to disrupt and destroy Federal railroads and commerce above the Mason-Dixon Line. Lee failed to gather food and supplies from the riches of the Keystone State. Lee failed to sway enough voters to dethrone the Republican majority in Congress. Lee failed to persuade Britain and France to officially recognize the Confederate cause. And, perhaps most important, Lee failed to whip the Yankee army on its home turf.

The biggest loser in the South’s 1862 invasion of the North was Robert E. Lee.

Why, then, is George McClellan consistently branded the loser?

As we ruminate on this inexplicable reversal of roles, let’s consider specific instances where McClellan’s proactive actions stymied Lee’s initiatives. If we ignore preconceived prejudices against McClellan, perhaps we can comprehend this campaign from a different point of view.

Four dates offer specific instances of McClellan’s aggressiveness against Lee.

Thursday, September 11, 1862

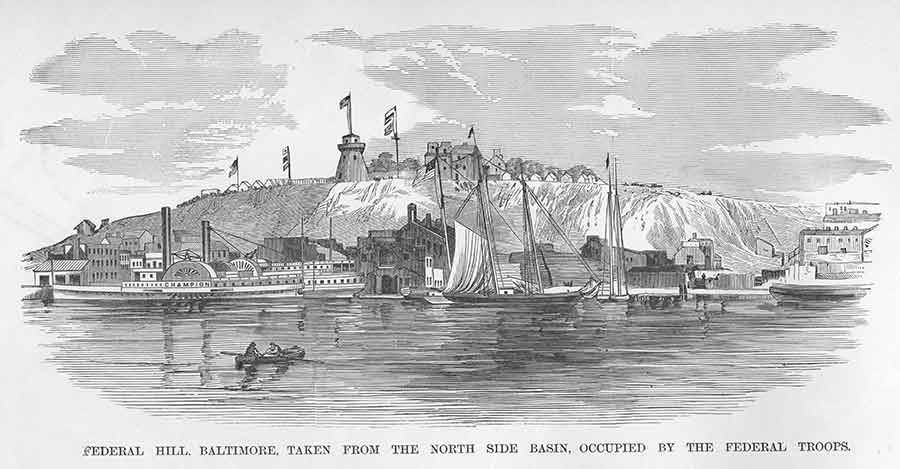

No one in the North knew what Lee’s targets would be. But when his army splashed across the Potomac River that first week of September, Baltimore, not Washington, surprisingly seemed to be the most endangered city in the United States.

Federal authorities had anticipated a strike against the Northern capital since the tense days following the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run. In the subsequent 14 months, Washington had transformed into the most heavily fortified city on the planet, defended by nearly 500 cannon and 160,000 soldiers. Few feared for Washington’s safety as Lee halted his invasion force at Frederick, Md., only 40 miles northwest of the capital.

Unlike Washington, Baltimore was virtually defenseless. Fort McHenry, the War of 1812 bastion protecting Baltimore Harbor, was useless against a land force, and the few Union earthworks on Federal Hill were designed not to protect against attack, but to hold hostage the city’s secessionist residents.

McClellan focused upon Baltimore and its vulnerability as his first order of business. He had no choice. Baltimore was where the Washington branch of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad connected the seat of the federal government to the rest of the United States. This lone artery, if severed, would fatally isolate Washington from the remainder of the country.

McClellan knew instinctively, and his military mind confirmed conclusively, that Lee’s logical strategic target was Baltimore. Before the war, Baltimore, in the slave state of Maryland, was the South’s largest city and largest port, with a population at 212,000—more than New Orleans’ 168,000. The sympathies of the majority of Baltimore’s population aligned with the Confederacy, and many Baltimoreans fought in Lee’s army. Baltimore and Alexandria, Va. (just across the Potomac from the capital) were the first two cities occupied by Union troops when war erupted, and the Baltimore riots of April 19, 1861, produced the war’s first combat fatalities (save for the deaths by accident of two Union gunners during the surrender of Fort Sumter five days earlier).

“All reports agree that Baltimore is their destination,” said Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, McClellan’s chief of cavalry. Department of the East commander Maj. Gen. John Wool informed President Abraham Lincoln: “Rebels proclaimed that they were going either to Philadelphia or Baltimore.” The governor of Pennsylvania learned from his spies: “Received full particulars concerning invasion of Maryland….Announced their destination Baltimore.”

Thus, McClellan’s first move was not toward Frederick—where Lee stood static roughly 50 miles west of Baltimore—but toward Baltimore. He placed this critical maneuver in the hands of his most experienced general, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, who was the only other man in McClellan’s army who had commanded an independent army.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]McClellan knew instinctively that Lee’s logical strategic target was Baltimore[/quote]

McClellan ordered Burnside to march his 9th Corps north, accompanied by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s 1st Corps (about 24,000 men), to interpose troops between Lee at Frederick and endangered Baltimore. “Should the enemy make any demonstration toward Baltimore…attack him vigorously,” McClellan instructed Burnside. The general then informed the War Department: “They shall not take Baltimore without defeating this army.”

Burnside moved with alacrity. “No time is to be lost,” McClellan warned. “I regard this movement as decisive, if successful.” Marching more than 40 miles in three days, Burnside promptly seized the National Road passing through a gap at Ridgeville, Md., effectively blocking any Rebel move toward Baltimore. Only after he was certain of Baltimore’s security—on September 11—did McClellan direct a concentration against Frederick and a move westward toward Lee.

Neither of the two most popular histories of this campaign (James V. Murfin’s The Gleam of Bayonets and Stephen W. Sears’ Landscape Turned Red) give any notice to McClellan’s prompt and prescient defense of Baltimore, and that maneuver’s attendant protection of Washington. Instead, they dwell on the yarn of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, McClellan’s boss and Union Army general-in-chief, who complained (one month after the invasion had ended) that McClellan moved only six miles per day during the invasion’s first week. Halleck’s assessment has been used to confirm McClellan as an indecisive, overly cautious procrastinator.

But, as shown, pursuing Lee at Frederick was not McClellan’s initial objective. First and foremost, Lincoln ordered him to protect Washington. And Washington survived this scare, not because of its impregnable defenses, but because McClellan defended its most vulnerable weakness: Baltimore.

Nothing else in the campaign could commence until Baltimore was safe.

Saturday, September 13

Students of Lee’s Maryland Campaign recognize this date as the “Lost Orders” day. “I have all the plans of the [R]ebels,” McClellan informed Lincoln, “and will catch them in their own trap.” The plans, of course, are Special Orders No. 191. Lee issued this directive four days earlier, dividing his army into four segments, with three columns directed to invest and eliminate the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, Va. Someone—still a mystery to history—lost a copy of Lee’s orders in a field outside Frederick.

McClellan has been excoriated for not moving rapidly upon receipt of this intelligence bonanza and for not destroying Lee while the Confederate army was divided, scattered and vulnerable.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]McClellan’s drive toward south mountain compelled Lee to withdraw his invasion force from the Pennsylvania line[/quote]

“The case [of finding Lee’s orders] called for the utmost exertion, and the utmost speed,” proclaimed Francis Palfrey in the first monumental work on the campaign, published in 1882 by Scribner’s under the title The Antietam & Fredericksburg, and included in its highly popular Campaigns of the Civil War series. Palfrey explained: “The opportunity came within [McClellan’s] reach, such an opportunity as hardly ever presented itself…and he almost grasped it, but not quite.”

Palfrey exercised enormous influence upon Murfin, who wrote 80 years later: “There can be found no plausible reason for McClellan’s delay in moving…immediately upon receipt of the [Lost Orders].…His most fervent supporters can offer no excuse for such negligence.”

Yet the harshest of McClellan’s critics is Sears, who dedicated several years plowing through McClellan’s voluminous archives at the Library of Congress, writing not only his Landscape Turned Red campaign history but also a McClellan biography. Sears presented McClellan as irresponsible:

A full eighteen hours would pass before the first Yankee soldiers marched in response to the discovery. No doubt had the situation been reversed and a Lost Order presented to Robert E. Lee, that general would have had Jackson’s foot cavalry on the march within the hour and every other man in his army who could carry a rifle moving after them within two.

This purported doctrine of delay is spurious and downright false. Sears chose only one bit of evidence to justify this claim, ignoring a preponderance of proof to the contrary. The one shred of evidence, frequently cited, was a 6:20 p.m. missive on September 13 ordering 6th Corps commander Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin to move the next morning (hence the 18-hour delay) to relieve Harpers Ferry.

But this was hardly McClellan’s only action. On the afternoon and early evening of the 13th, Little Mac had Burnside’s entire wing (24,000 soldiers) moving toward Catoctin Mountain 20 miles northwest of Frederick, with the 9th Corps conducting night marches to cross that barrier and launch farther west toward South Mountain. Correspondence in the Official Records confirms these movements, but the best validation comes from Lee’s reaction to them.

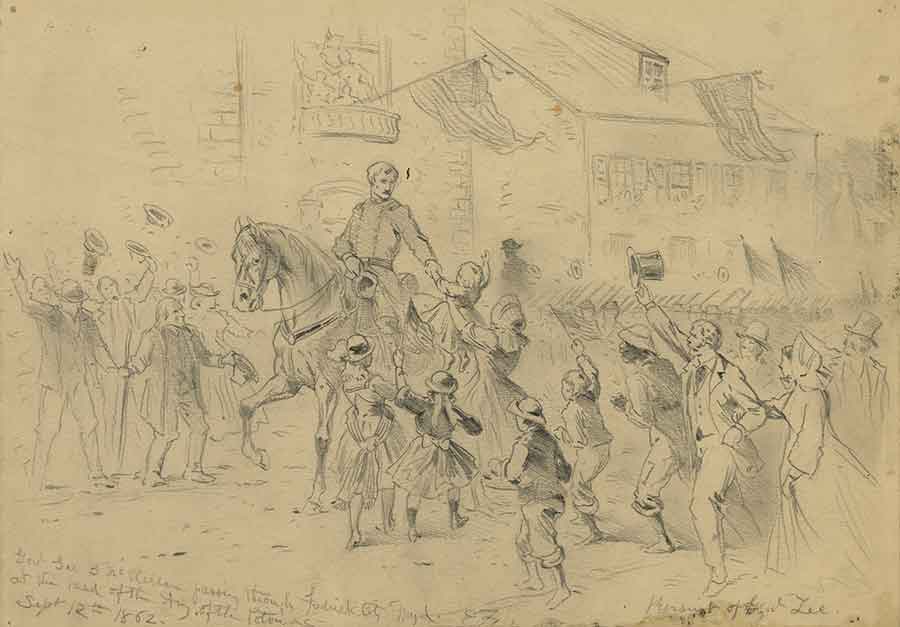

Lee stood within sight of the Mason-Dixon Line on September 13, waiting at Hagerstown for Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson to complete his Harpers Ferry mission. As he gazed into Pennsylvania, already directing the van of his army to Middleburg, Md. (State Line today), Lee’s hopes of achieving independence for his new nation never appeared so near.

That vision collapsed on the night of September 13. “[McClellan] immediately began to push forward rapidly,” reported the Southern commander. Take note of Lee’s exact words: “immediately” and “rapidly.”

Lee’s movements during the next 24 hours revealed undeniable failures. McClellan’s drive toward South Mountain compelled Lee to withdraw his invasion force from the Pennsylvania line; forced Lee to fight an undesired battle at the mountain’s gaps to save his scattered forces; required Lee to retreat for the first time as an army commander; and, worst of all, coerced Lee to write the most distressing words of his career to that point—“The day has gone against us. This army will go by Sharpsburg and cross the [Potomac] river.”

Lee’s invasion had been canceled.

Tuesday, September 16

Lee’s decision to retreat from South Mountain meant he had every intention of returning to Virginia. McClellan’s unexpected arrival and prudent advances had ruined his offensive. Jackson’s tardiness at Harpers Ferry had doomed his momentum. Desperation consumed Lee as he temporarily bedded down his weary and hungry army near Antietam Creek.

But his sullen mood reversed about noon on September 15. Lee, finally, received a welcome message: “Through God’s blessing,” wrote a humbled Stonewall, “Harpers Ferry and its garrison are to be surrendered.” At that moment we don’t know Lee’s thoughts, but we do know the possibilities he could now consider.

Lee’s best prospect was not to stand, but to move. Pennsylvania was near. The border and the Mason-Dixon Line—only 22 miles distant from Lee’s position at Sharpsburg—was just one day’s march. Invasion of Pennsylvania, from the outset, had been his principal goal. The way was open. A good road—the Hagerstown–Sharpsburg Turnpike—ran due north unimpeded. If Jackson could rush from Harpers Ferry (a one day’s march), Lee could reunite his army, drive it north, and then move upon prized Pennsylvania.

But if Lee moves on September 16, there is no Battle of Antietam. Lee’s option to move north depended absolutely on the Union army’s remaining in place on Antietam Creek’s opposite bank, his assumption being that McClellan would not cross the creek.

Lee’s assumption appeared reasonable. McClellan had a reputation for deliberateness and methodical plodding. Always believing himself outnumbered, he consistently hesitated, pleading for reinforcements, and awaiting perfect conditions before striking. Antietam’s most popular historians confirm this preference. Arguing that September 16 was McClellan’s best opportunity to vanquish Lee, their censorship has been harsh.

“There is no censure too strong for his delay,” Palfrey exclaimed. “It is an ungrateful task to be always finding fault, but…the perniciousness of the mistake which McClellan made in delaying his attack cannot be too strongly insisted upon.” Murfin was equally blunt: “Once again McClellan was obliging [Lee], Lee made the best of every advantage offered him; McClellan tossed away every one Lee gave him.” Sears offered his own harsh assessment: McClellan “plodded through the day,” perhaps missing “the best chance of all.” Sears scolded McClellan for his caution, resulting in perceived ineptitude. “Rather than act he would only react, and in this particular attitude of command [across from Lee along the Antietam], he surrendered much of the initiative to his opponent.”

These critics ignore an important point—McClellan moved. He sensed opportunity. On September 16, for the first time (in his mind), he outnumbered Lee. He knew for a fact that six of Lee’s nine infantry divisions had been dispatched to Harpers Ferry, based on the contents of the “Lost Orders.” Since two-thirds of Lee’s army had not yet arrived at Sharpsburg, even by McClellan’s strange math, he held the advantage over Lee—if he struck quickly.

But what if McClellan’s main target was not Lee, but the road to Pennsylvania?

McClellan didn’t know Lee’s thinking, but as a strategist he certainly could surmise Lee’s intentions. McClellan had divined Pennsylvania to be a primary Confederate target since the invasion’s outset. He knew Lee was concentrating at Sharpsburg, and he could interpret this two ways: Either Lee expected to fight there, or the Confederate commander intended to move north from there. If McClellan were to capture the Sharpsburg–Hagerstown Turnpike and block Lee’s avenue northward, he could eliminate the “move” option, and produce an outstanding outcome—defeating the Rebel army’s invasion.

The Union commander seized the occasion. By afternoon and evening of September 16, McClellan had moved nearly 23,000 soldiers from his 1st and 12th Corps—about one-third of his total force—around the Confederate left flank. And they took the road! Consider McClellan’s wise preemptive action. About two miles north of Sharpsburg, he had blocked Lee’s line of advance into Pennsylvania, and had done so without a battle, indeed barely firing a shot!

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]McClellan responded to the Confederate threat at Williamsport with alacrity and force[/quote]

McClellan’s prescient move on September 16 constituted the demise of Lee’s invasion strategy. The most famous Southern general of the war had been outsmarted, outflanked, and outmaneuvered by the most harshly criticized Union general of the war.

Capture of the Sharpsburg–Hagerstown Pike had forced Lee into a sorry predicament. Now blocked and unable to move north, the Confederate commander faced two choices, neither good. He could fight another unwelcome battle, at an unwanted time at an undesired location, or he could call off his once-promising invasion and retreat into Virginia.

Flushed with success and well-earned achievement, McClellan telegraphed his wife Mary Ellen the evening of the 16th: “[H]ave no doubt delivered Penn[sylvania] and Maryland. All well and in excellent spirits.” The next day’s vicious fighting, however, would produce the bloodiest, most horrific one-day battle in U.S. history, with nearly 22,000 dead, wounded, captured, or missing by its conclusion.

Sunday, September 21

Lee’s withdrawal from Sharpsburg on the evening of September 18 did not end the campaign. In fact, Lee determined to continue the invasion immediately: “[T]he army was immediately put in motion toward Williamsport,” Lee informed President Jefferson Davis. Thus, Lee’s retreat from Antietam was, in effect, merely a repositioning of Confederate forces. The commander’s new scheme involved a difficult flanking maneuver along the Virginia bank of the Potomac that required not one, but two river crossings.

The movement commenced the night of September 18-19, as the Rebels returned into Virginia via Boteler’s Ford below Shepherdstown. Then Lee expected to race his army north toward Williamsport: a 19-mile gallop. The plan then called for re-crossing the Potomac at Williamsport and returning to Maryland, where Lee could “threaten the enemy on his right and rear and make him apprehensive for his communications.” Lee’s new destination was Hagerstown, returning to his previous invasion launching pad.

Accomplishing this bold maneuver required two things: First, to secure a crossing at Williamsport; second, to make sure his rugged veterans could march hard and fast enough to outrace the enemy to that river crossing town.

To inaugurate this new offensive, Lee ordered cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart to accomplish the first objective. During the night of the 18th, as Lee’s main army withdrew below Shepherdstown, Stuart crossed the Potomac above that village, then bolted north, re-crossing the river at Mason’s Ford and seizing Williamsport in the early morning hours of September 19. A battalion of the 2nd Virginia Infantry of the Stonewall Brigade arrived to add muscle, and the Confederates promptly established a bridgehead for the renewed invasion.

McClellan quickly discerned what Lee was up to. He wasted no time, responding to the threat at Williamsport swiftly with force. First he rushed his most mobile force to the point of danger, ordering two brigades of Pleasonton’s cavalry and one battery of artillery toward the town. He followed that initial show of power with Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch’s division of 6,000 fresh infantrymen of the 4th Corps. To further bolster his strength, he directed Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin’s 6th Corps to concentrate against the position.

By September 21, McClellan had maneuvered nearly 18,000 men toward Williamsport to block Lee’s initiative. Stuart witnessed “the enemy drawn toward my position in heavy force,” and he quietly withdrew into Virginia. Lee’s renewed offensive promptly ended, less than 36 hours after it began. The Rebel commander expressed disappointment to President Davis: “It was my intention to re-cross the Potomac,” and to renew the invasion, Lee wrote on September 25. “[B]ut the condition of the army prevented it.”

True. Lee’s army was worn out. Of more significance, however, is the fact that Lee made no mention of McClellan blocking him at Williamsport. Not a word about McClellan stealing away the renewed offensive through the Union commander’s aggressive countermeasures.

Most historians have followed Lee’s lead. Dutifully, they have repeated his excuse on why he quit: His army no longer could “exhibit its former temper and condition.…I am, therefore, led to pause.” Few, if any at all, have given McClellan credit as the principal cause for that—except, perhaps, for Abraham Lincoln. The president was convinced Little Mac had achieved victory. McClellan had, indeed, rid the North of the invader, protected Washington, and wounded Lee with two stunning battlefield defeats. So confident was the president with this finale that the very next day he issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

Recently retired from the National Park Service, Dennis E. Frye served for 20 years as chief historian at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park and is a co-founder and past president of the former Civil War Trust and the Save Historic Antietam Foundation. This article is adapted from his latest book, Antietam Shadows: Mystery, Myth & Machination.