Wasteful Federal attacks at New Hope Church during the Atlanta Campaign resulted in a lopsided Confederate victory

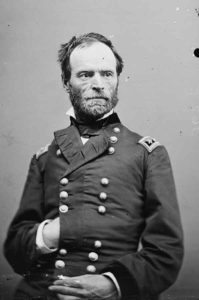

[dropcap]U[/dropcap]nion Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman achieved a reputation as a deft strategist and flank marcher against his Confederate opponents during the 1864 march to Atlanta. But when he committed his troops to battle in Georgia, it was invariably in frontal assaults that were anything but artful. At New Hope Church, on May 25, he blustered his way to defeat by telling his officers that there weren’t “twenty Rebels out there,” when in fact 4,000 veteran fighters were in place and ready to slug it out with their enemies. It’s not a very flattering story of the Northern war hero, one that is usually swept under the rug. Here’s how it happened.

In the spring of 1864, Sherman, as head of the Military Division of the Mississippi, commanded 110,000 troops near Chattanooga, Tenn. Three separate armies made up his force: Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland, Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee, and Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio, which was actually only two infantry divisions.

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant ordered Sherman to march into Georgia and defeat the Confederate Army of Tennessee. That army, commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston, numbered 55,000 troops in late April, with two infantry corps commanded by Lt. Gens. William J. Hardee and John B. Hood. Sherman thus enjoyed a 2-to-1 numerical superiority as he got his forces marching on May 6. “Cump” used those numbers to outflank Johnston from his position near Dalton within a week. Then, after the Confederates retreated to Resaca, the two sides launched sorties against each other May 14–15. When Union infantry again flanked Johnston’s left, threatening to cut his supply line, the Western & Atlantic Railroad back to Atlanta, the Southern army kept marching south through Calhoun and Adairsville. Unable to give battle at Cassville, Johnston crossed the Etowah River on May 20.

Johnston halted his retreat at Allatoona Pass, at the 175-foot gap in the Allatoona Mountains through which ran the Western & Atlantic Railroad. There he dug in, hoping Sherman would attack. But Cump knew the formidable terrain from his Army service of the 1840s, and after giving his troops a few days to rest and resupply, for the first time in the campaign he marched away from the Western & Atlantic. Aiming to flank the Rebels off their high ground by a wide sweep to the southwest, he instructed his troops to be ready to set out on May 23, with wagons carrying 20 days’ supplies.

Two weeks into the campaign, Sherman maintained numerical superiority. On the 21st he wired Army chief of staff Henry W. Halleck in Washington that he expected to cross the Etowah River with “80,000 fighting men.” Johnston had suffered his own losses, but these were more than made up for by at least 14,500 reinforcements that included garrison soldiers from Mobile and the Savannah-Charleston area, but most important Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk’s Army of Mississippi—three infantry divisions that essentially became Johnston’s third corps.

The Union troops got marching early on May 23 and crossed the Etowah at several places that day, slowed where Rebel cavalry had burned bridges. As his objective Sherman staked out Dallas, a country-crossroads some 15 miles southwest of Allatoona. Once his forces got there, he figured the enemy would have to fall back. Northern soldiers were relieved that they would be maneuvering and not attacking. “Allatoona Mountains,” observed one Ohioan, “are not the thing to run squarely against.”

Johnston’s cavalry kept him informed of the Federals’ movement. Deducing the Dallas area to be Sherman’s goal, the Confederate commander ordered Hardee’s and Polk’s corps to start marching west on May 23. Hood stayed behind at Allatoona, watching for possible enemy river crossings.

On May 24 Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland marched in the most direct southward route toward Dallas. Schofield was on his left, McPherson to the right. Brigadier General Edward McCook’s cavalry rode ahead of Thomas’ infantry, tussling with Confederate cavalry. That day Hardee approached Dallas as the left of Johnston’s force. By hard marching, the Southerners beat Sherman’s forces to their objective point.

Cump was forced to realize this when Union cavalrymen covering McPherson’s march brought in prisoners from Hardee’s Corps. There was more disconcerting news on the 24th. A dispatch taken from a captured Rebel courier disclosed that Johnston was shifting his forces toward Dallas. “This information was immediately forwarded to headquarters,” noted one of Thomas’ staff officers, “thus early, Sherman learned of Johnston’s plans.”

Hardee’s arrival at Dallas effectively blocked Sherman’s wide maneuver from the railroad. From Hardee’s position Polk’s corps extended northeast and Hood’s infantry left Allatoona on the 24th, marching toward the new line. That night they halted a few miles from New Hope Church, a little crossroads Methodist meeting house four miles northeast of Dallas. The next morning, May 25, Hood continued his progress toward New Hope. The Confederates reached it around 10 a.m. Hood’s divisions arrayed on a slight ridge from left to right: Maj. Gens. Thomas C. Hindman’s, Peter Stewart’s, in the center at the church, and Carter L. Stevenson’s. Hood’s Corps thus formed the right of the Army of Tennessee with Stevenson’s Division on the far flank. Johnston’s six-mile line was in place by noon.

Sherman had his men marching southeast in a wide front on the 25th. In the middle were the Army of the Cumberland’s three corps, and Thomas’ orders called for his troops to march toward Dallas. Hooker’s 20th Corps was on the road from Burnt Hickory with three divisions. Of them, Brig. Gen. John W. Geary’s held the center. Geary and his men were up and moving by 7 a.m. As they approached Pumpkin-vine Creek, Rebel horsemen were burning the bridge. The Federals put out the fire, saved the bridge, and about 10 a.m. resumed their march. But Geary had taken a wrong road. Instead of Dallas, he was heading for New Hope Church. Thomas approved the detour.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The rebels were ready[/quote]

That morning, Confederate watchmen on Elsberry Mountain had spotted Yankee dust columns bearing from the north. General Hood sent forward Colonel Bushrod Jones’ 32nd/58th Alabama and a battalion of Louisiana sharpshooters as skirmishers. A mile or so south of the creek, Geary’s front encountered the advance elements. Hood soon ordered out several other regiments to develop the Union strength and to hold them back while he strengthened his line. “A sharp engagement” ensued, Geary later reported, in which he brought up reinforcements to drive off the Rebels. Geary halted and deployed. Generals Thomas and Hooker were with him and Hooker called up Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield’s and Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams’ divisions. Thomas ordered his other corps to push ahead.

Confederates coming back in from the firefight with the Yankees brought with them a prisoner who blurted that Geary’s division, and Hooker’s whole corps, were coming. The Rebels were ready. The very day before, Hood had issued a general order to his troops. “The lieutenant-general commanding desires to say to the officers and soldiers of his command,” it read, “that in the coming battle their country expects of them victory.”

Once the line was laid out, Hood’s troops fortified somewhat indifferently. Stewart’s Division would probably bear the brunt of an attack, as the road Geary’s column was taking led straight to New Hope Church. Stewart arrayed his four brigades: Brig. Gens. Alpheus Baker’s Brigade on the right, Henry Clayton’s in the center, Marcellus Stovall’s on the left, and Gibson’s in reserve. Though expecting a battle, General Stewart later wrote that Clayton’s and Baker’s troops only “piled up a few logs.” Stovall’s Georgians, according to Stewart, “were without any defense,” save for the upright headstones in the church graveyard.

To bolster the line three batteries of artillery were brought up and rolled into place. Sometime after mid-afternoon General Johnston rode along the position. “He told us that the enemy were ‘out there’ just three or four hundred yards,” remembered Lt. Bromfield Ridley of Stewart’s staff.

Indeed they were, but it took them time to come up. The country was well wooded, perforated only with “by-paths and mountain roads,” as General Williams described it. Williams led his division on a brisk five-mile march to approach Geary. Butterfield arrived, too, allowing Hooker to plan the attack that General Sherman, it turns out, was now calling for.

Sherman had set out on May 23 believing that Johnston, forced from Allatoona, would fall back to Marietta, 15 miles to the south. Instead, he had learned that Johnston’s army now blocked his path at Dallas and that today, May 25, Thomas’ forces were slowing down before enemy resistance.

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Stone, one of Thomas’ staff officers, ran into Sherman, “dismounted, by the roadside, showing great impatience,” as he later recounted. Cump was upset that his troops were not making more progress. When Stone informed him that Williams was on his way to help Geary, the commanding general grabbed an envelope, jotted a few words of instruction for Thomas, and “somewhat testily” told him, “Let Williams go in anywhere as soon as he gets up. I don’t see what they are waiting for in front now. There haven’t been twenty rebels there to-day.”

Thomas sensed that Sherman was in no mood for dithering. He passed on the order to Hooker, who by 5 p.m. finally had his troops in formation: Williams on the right, Butterfield the left, and Geary behind. The infantry arrayed in column of brigades—meaning one behind another. This narrower front gave commanders better control of their troops, especially in wooded terrain. Moreover, assault-in-depth promised quicker exploitation of success if the attack actually broke the enemy line. The narrower front, however, gave defenders advantage as well. Though Hooker’s corps overwhelmingly outnumbered Stewart’s Division—some 16,000 to about 4,500—Williams’ and Butterfield’s two-brigade front was actually shorter than that of Stewart’s, giving the Southerners opportunity for crippling enfilade fire. The main disadvantage of column formation, though, was that, packed behind their comrades, attackers in the rear ranks could not fire.

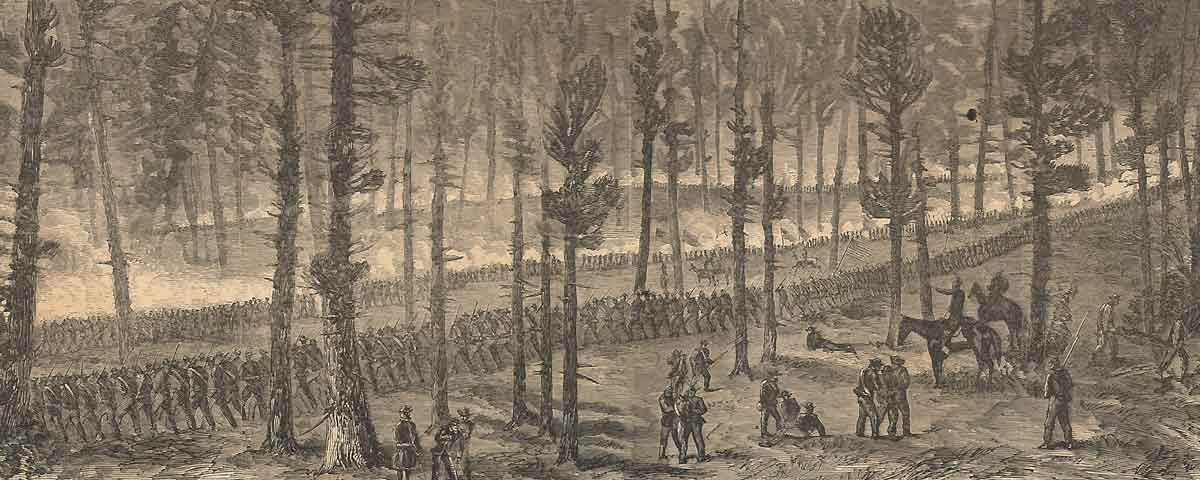

General Williams ordered the advance around 5 p.m. His troops made contact with the Rebel pickets, driving them back. The Federals pressed through the woods as storm clouds gathered overhead. “The trees gave some protection to the men,” noted one officer, “but it was a severe ordeal for men to pass through.” At one point they descended into a deep ravine—the “hell hole,” as it came to be called—then had to clamber out to continue their advance. Approaching the enemy works on the high ground ahead, they came under heavy fire. Butterfield joined in the fight to the left, and Geary came up to reinforce Williams.

But the Union infantry never got close to their objective. One Federal recalled that his line advanced to 60 yards away, “when we halted; for we had lost so many men, and had become so disorganized in the march through the timber and brush that the impetus of our charge was gone.” Confederate artillery was bloodily effective. Colonel John Coburn, leading one of Butterfield’s brigades, described it this way: “The enemy poured in upon us a tremendous fire of artillery. Shells, grape-shot, canister, railroad spikes, and every deadly missile rained around us.” At least one Northern regiment, according to an officer, “rushed in disorder to the rear.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The Union infantry never got close to their objective[/quote]

Colonel Robert Beckham, Hood’s chief of artillery, personally supervised his guns’ enfilading fire. “They poured into us canister and shrapnel from all directions except the rear,” Williams later lamented. Well afterward, Geary wrote that “canister and shell from the enemy were heavier than in any other battle of the campaign.” Colonel Archibald McDougall of the 123rd New York was one of the casualties. “After a discharge from their battery I heard a cry just back of me,” recorded Sergeant Rice Bull in his diary, “turning, I saw the Colonel stagger and fall.” Borne to the rear, he died a month later of his wounds.

After two hours, Hooker’s assault was over and rain began to fall. Those Federals who could do so retreated to their lines. Some held on to tenuous positions and exchanged rifle fire well into the darkness. Skirmishing continued the next day, but the hard fighting was over.

Hooker totaled his Battle of New Hope Church casualties at 1,664 killed, wounded, and missing. Alpheus Williams’ division bore more than half, with 870; the rest were in the divisions of Geary (376) and Butterfield (418).

Hooker’s Ironclads

The Union Army of the Cumberland’s 20th Corps was composed of soldiers who had cut their battle teeth in the Eastern Theater fighting in the 11th and 12th Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Following Gettysburg’s bloodletting, both corps were sent west to help relieve the Siege of Chattanooga, and they would remain thereafter in the West. On April 4, 1864, an order by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman formally combined the two organizations into the 20th Corps with Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker as the commander. Lieutenant Colonel Charles Morse of the 2nd Massachusetts recalled that when 12th Corps commander Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum issued his farewell order, he tried to address the men, but “was so affected he could hardly speak, the tears running down his cheeks….” Morse stoically wrote, “Well, the old institutions are broken up, and we must bear it as philosophically as possible.” The Union soldiers bore the change well. The Army of Tennessee respected the 20th Corps, and nicknamed its troops “Hooker’s Ironclads” for their fighting ability. Hooker, however, was not destined to remain in command of the corps. The tension between Sherman and Hooker that manifested after the fight at New Hope Church came to a head after the July 22 Battle of Atlanta. When “Fighting Joe” did not get command of one of Sherman’s armies after the death of Maj. Gen. James McPherson in that fight, he resigned and Maj. Gen. Alpheus Williams took command of the 20th Corps. – D.B.S.

Joe Johnston placed his loss on May 25 as “about 450 killed and wounded.” General Stewart reported 300-400 casualties from his repulse of Hooker’s assault. Baker’s lightly engaged brigade lost perhaps 45 men, Gibson’s in reserve, maybe 75. Clayton’s four regiments tallied 172 casualties. General Stovall’s biographer posits 18 killed, 122 wounded. Major John W. Eldridge’s artillery battalion had 43 men killed and wounded. The Confederate losses, around 475—contrasted with the enemy’s 1,664—clearly marks the Battle of New Hope Church as a Confederate victory.

Hooker’s formation had negated his numerical advantage. Even a Confederate observed that the enemy’s formation meant that “the rear lines were exposed to the same danger as the front lines, but could not fire on account of the front lines being in the way.”

Rough terrain impeded the attackers. A member of the 3rd Wisconsin wrote that “the country was heavily timbered, and underbrush so obscured the view that it was impossible to see in any direction more than a few yards.” More important, Southerners held the high ground, and many were protected by log earthworks on a site of their choosing. As Stewart observed, “our position was such that the enemy’s fire passed over the line to a great extent.”

Confederate artillery was another factor. One Southerner claimed that their guns fired 1,560 rounds during the two-hour engagement. Dr. H.Z. Gill, surgeon in chief for Williams’ division, later reported, “our men suffered severely, especially from his grape and canister, at short range.”

The Itch

Campaigning in the rough, wooded region of North Georgia was not easy for either army. During the movements that led to New Hope Church, Quartermaster Sergeant Joel D. Murphree of the 57th Alabama wrote his wife of the travails he faced, and exhibited a sarcastic sense of humor as he did so: “Ursula, there is no chance to keep clean in the army while on the tramp as we have been for the last two weeks. I am as dirty as a hog and nearly as lousey…I must say something or you might think I had found a wife up here for the present, and have laid you on the shelf. No such good luck however, in fact I have been in no situation for sweetheart hunting. I have been torment equal to Job of old until last week. I have been afflicted with Diarrhea, Itch and Piles and part of the time lousey, but I thank the Lord for His blessing I am now clear of all. After a general and thorough greasing for about a week for the itch I yesterday washed off and put on clean clothes from the skin out.” – D.B.S.

At one point in the battle, the concerned Johnston had sent a message asking Stewart if he needed help. “My own troops will hold the position,” he answered calmly. They did, pouring murderous musketry against the enemy ahead. A spirit of jocularity even caught on among Stewart’s men as they laid down their volleys. When the division commander rode behind the firing line, his son, Lieutenant Robert C. Stewart, called out, “Now, father, you know you promised mother that you would not expose yourself to-day!” The men in the ranks took up the cry, laughing and repeating it down the line.

The Confederate success was a comparatively small one. But after several weeks of giving up ground, any good news was welcome to the home front. The Yankees’ attacks, the Atlanta Intelligencer beamingly announced, “were met firmly and repulsed with great slaughter.” Those in the ranks could be even more effusive. “Both officers and men never performed their duty better,” reported Captain Rufus Asbury of the 52nd Georgia, “they were determined to teach the invader that they were fighting freemen, who knew their rights and would dare maintain them.”

Johnston’s announcement to Richmond, telegraphed on the 28th, was more reserved: “On the afternoon of the 25th Major General Stewart was attacked by Hooker’s corps, which he repulsed with considerable loss.” Sherman was equally laconic, mentioning to McPherson that night that Hooker “had a pretty hard fight.” In his campaign report, Sherman credited Hooker with having driven back the Confederate skirmishers to New Hope Church. But the Rebels, “having hastily thrown up some parapets,” stood their ground “and a stormy, dark night having set in, General Hooker was unable to drive the enemy from these roads.”

Sherman had no reason for malediction against the 20th Corps commander, but after the battle, he met Hooker and berated him for taking too long to bring up Williams and Butterfield. He believed the delay had given the Confederates time to bring up reinforcements.

After a few days’ more fighting along the Dallas–New Hope lines, Sherman got his forces moving back to the Western & Atlantic Railroad, and during June he again repeatedly outflanked the Rebel army. After Johnston retreated across the Chattahoochee he was relieved of command, but Sherman’s capture of the prize city on September 2 helped President Abraham Lincoln win a second term and thereby helped the North to finally win the war.

William T. Sherman’s historical reputation basks in the capture of Atlanta—overshadowing the tactical errors he committed along the way. Writing of Hooker’s corps on May 25, he later wrote, “I ordered it to attack violently and secure the position at New Hope Church.” Somewhere in the annals of Sherman’s glorious career must be found an occasional page or two reminding students that even great generals can blunder, ordering their men into frontal attacks that are bound to fail.

Stephen Davis is author of several books, including What the Yankees Did to Us: Sherman’s Bombardment and Wrecking of Atlanta. He is currently working on a book about how the Atlanta Intelligencer covered the war.