If you had the opportunity to stop a war that had been raging for years, killing your countrymen and innocent people abroad and leaving families devastated, would you do it? Or would you hesitate first to weigh your odds of gaining power at the victims’ expense? What if a rival of yours were about to stop that war? Would you put peace and human life first, or would you try to sabotage that rival — and allow other people to continue dying so you could get ahead?

Selfishness and sabotage were Richard Nixon’s answers to those questions — a fact which, no matter what people may think about Nixon’s politics, is incontrovertibly revealed by this unusual envelope delivered to the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library in June 1973 by former President Johnson’s National Security Adviser Walt Rostow.

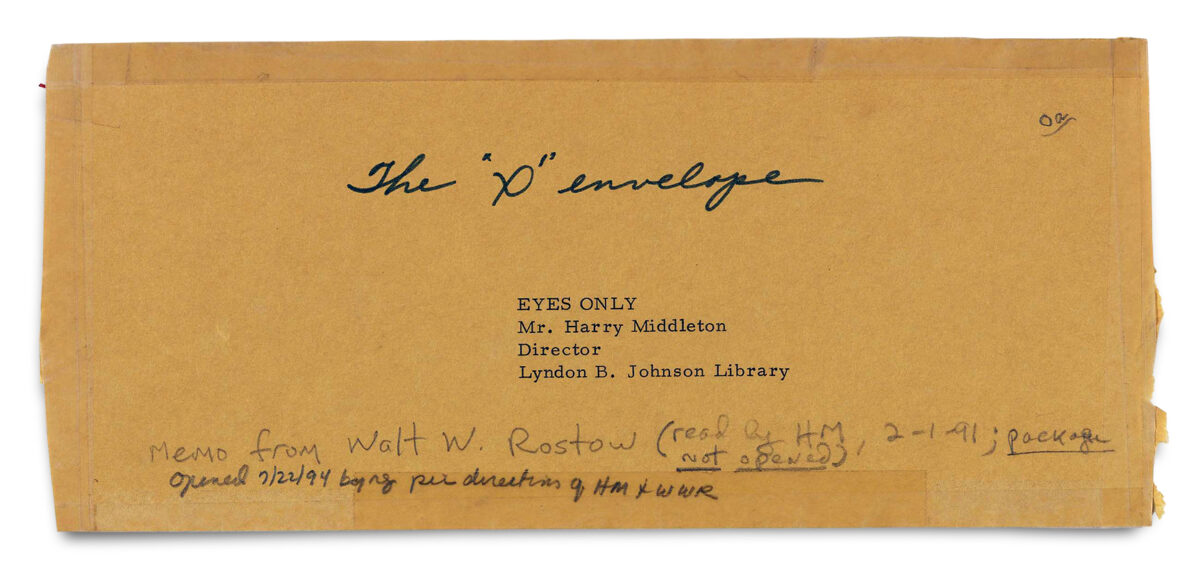

This is known as the “X” envelope. “Top Secret,” reads Rostow’s scrawling handwriting on the reverse side. “To be opened by the Director, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library not earlier than fifty (50) years from this date, June 26, 1973.”

The envelope contained records of an FBI wiretap that LBJ had ordered on the phones of the South Vietnamese Embassy in Washington, D.C. Wiretapping sounds scandalous enough — it might even remind you of Watergate. This particular wiretap was the result of a tipoff to LBJ that made him suspicious enough to want to pin down a shadowy presence — a person interfering with his peace talks to end the Vietnam War.

Johnson had apparently come pretty close to reaching a peace deal with South Vietnam, but something — actually, someone — was gumming up the works. A political rival in the shadows would rather see the war continue to help him gain power. The saboteur was none other than Nixon, who took it upon himself to contact South Vietnamese President Thieu to effectively bribe him out of agreeing to peace terms.

Although FBI wiretaps revealed this meddling, Johnson didn’t want the American public to know about it, feeling that it would “throw the country into turmoil,” according to the National Archives. By late January 1973, LBJ was dead — of a heart attack, less than one week before the Paris Peace Accords were signed that ultimately ended the war. Perhaps he died burdened by the acute awareness that peace had actually been within reach five years earlier in 1968.

How many people would have lived if Johnson’s peace negotiations been allowed to succeed in 1968? How many names would not be inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall today? How many families would not have been torn apart?

Working on Vietnam magazine, I read stories of men who displayed staggering heroism — men who sacrificed their lives to save their friends, who lost their limbs, who were taken prisoner and abused, whose whereabouts are unknown today and whose families were broken by their loss and still mourn for them. The idea that a chance to spare their suffering was deliberately foiled by a politically ambitious person is diabolical to say the least.

This ugly truth did not emerge during the Watergate scandal. The sealed envelope containing the evidence was first opened in 1994. Many people are still not aware of its contents even today. We can only wonder at the families that would have been built and the human accomplishments that would have enriched America and the world had more lives been spared and if Nixon had been willing to put the good of others before himself.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.