Among all female World War II fighters to receive the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, Nina Andreyevna Onilova was one of the most remarkable, rising from obscure origins to become a deadly machine gunner.

Born on April 10, 1921, to a Ukrainian peasant family in the village of Novo-nikolayevka on the Crimean Peninsula, Nina lost both parents at age 11 and grew up in an orphanage.

“I have no family of my own, and therefore all the people are my family,” she later wrote.

A Life-Changing Movie

The young girl’s life changed forever when she saw the film “Chapaev,” released across the USSR in 1934. The moody Soviet propaganda film centered on the exploits of Red Army commander Vasily Chapaev, a Communist hero of the Russian Civil War. With heavy emphasis on peasants warring against the elites, the film brought Soviet ideals to the screen on a grand scale. Political messaging aside, the film had plenty of action and drama to entertain its audiences.

The movie was groundbreaking in its lead female character Anka, a machine gunner. In line with Communist propaganda, it was only natural for the film to depict a Soviet woman partaking in egalitarian political struggle. But instead of making Anka into a nurse or relegating her to a supportive noncombat role, the filmmakers portrayed Anka as a hands-on fighter.

This made the movie rare — and quite different from what was being seen in Western countries. While American audiences in 1934 watched Claudette Colbert’s ditzy heiress capering alongside Clark Gable in “It Happened One Night,” Soviet audiences that same year witnessed Anka, played by actress Varvara Myasnikova, romancing a soldier while wielding a firearm in guerilla warfare. During that time period, it was extraordinary anywhere in the world for a woman to be shown participating in combat — much more so behind a machine gun.

In accord with Socialist Realism style, Soviet filmmakers made Anka’s character appear down-to-earth. Neither superhuman nor glamorous, she is shown as an ordinary girl dedicated to the rugged lifestyle of a soldier. Although underestimated, she proves her abilities and ultimately earns the respect of her male comrades.

The film had a profound effect on young Nina, who was about 13 years old when it premiered. Her love of the epic military movie was more than just a passing fancy. Chapaev became her hero, and Anka became her role model. She wanted to follow in Anka’s footsteps — literally.

Like other young Soviet women, Nina spent her days working in a factory. However, when she was not working, she was studying machine guns. She joined a paramilitary club attached to her factory and got into a machine gun training course, which she passed with a rating of “excellent.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Soviet ‘Glass Ceilings’

Joining the Red Army in 1941, Nina applied to become a field medic in the 54th Rifle Division, also known as the Chapaev Division, in the Independent Coastal Army. The division had inherited a proud history, having actually been commanded by Communist hero Chapaev, the protagonist of Nina’s favorite film, during the Russian Civil War.

“What a joy it was for me!” she later wrote of her acceptance into the division. She had fulfilled a dream.

Why did she join as a field medic? It was the only way for Nina to go to war. Despite the egalitarian ideals of Soviet society, some men remained profoundly opposed to allowing women into positions of authority or roles perceived as traditionally male. In a society where men and women were proclaimed by the state to be equals, intrepid girls like Nina were in reality struggling against glass ceilings. Despite her hopes, Nina learned through experience that real life was not just like the idealized socialist movies – and that many Soviet military men had attitudes that were certainly not utopian.

After reaching the front lines as a medic, Nina tried to join a machine gun crew. Despite all her training, she was not allowed to wield a machine gun or take on a combat role. She was forced to remain a nurse.

Baptism of Fire

Nina proved herself in battle against the Germans during the Siege of Odessa in 1941. She was treating the wounded when a machine gun nearby jammed. The enemy hemmed in closer as the crew fumbled to get the gun back into working order.

Nina ran to the rescue. She already had mechanical skills by practicing relentlessly in her free time back at the factory in handling machine gun parts. She quickly cleared the jam and took over firing the gun, cutting down advancing German infantry in a hail of bullets.

The crew were amazed by Nina’s ability and asked her to join them. Nobody questioned her value as a fighter anymore.

However she nearly lost her chance to fight again after being severely wounded by a mortar blast near Odessa in September 1941. She was kept in a hospital for almost two months and authorities did everything they could to make her stay there. However Nina obtained release after fiercely arguing with the medical board.

Defending Sevastopol

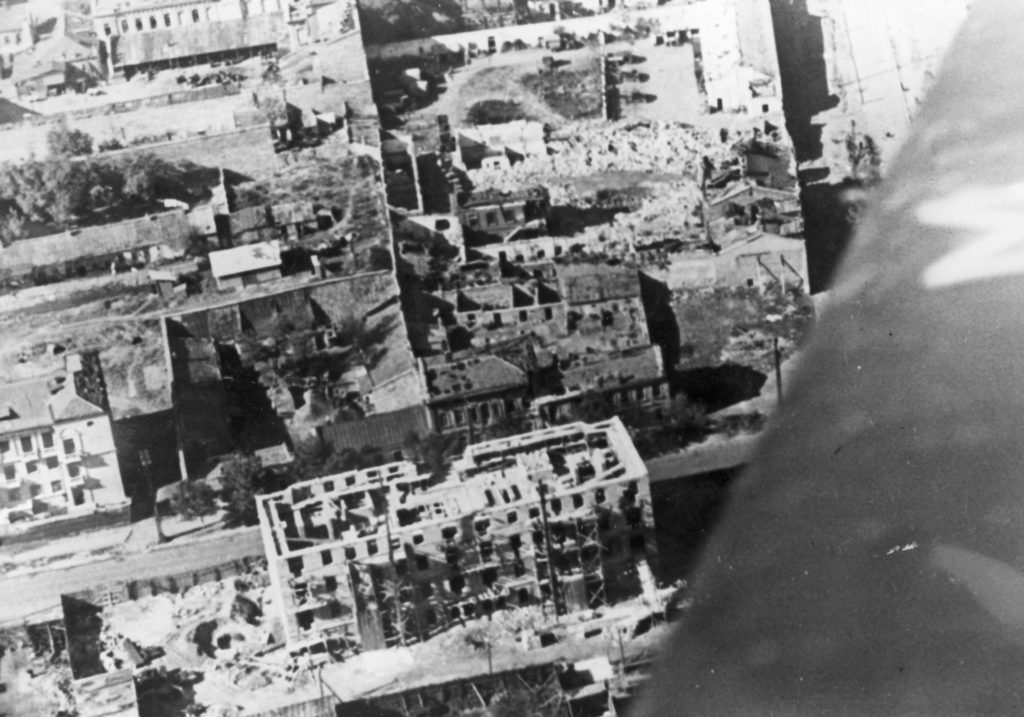

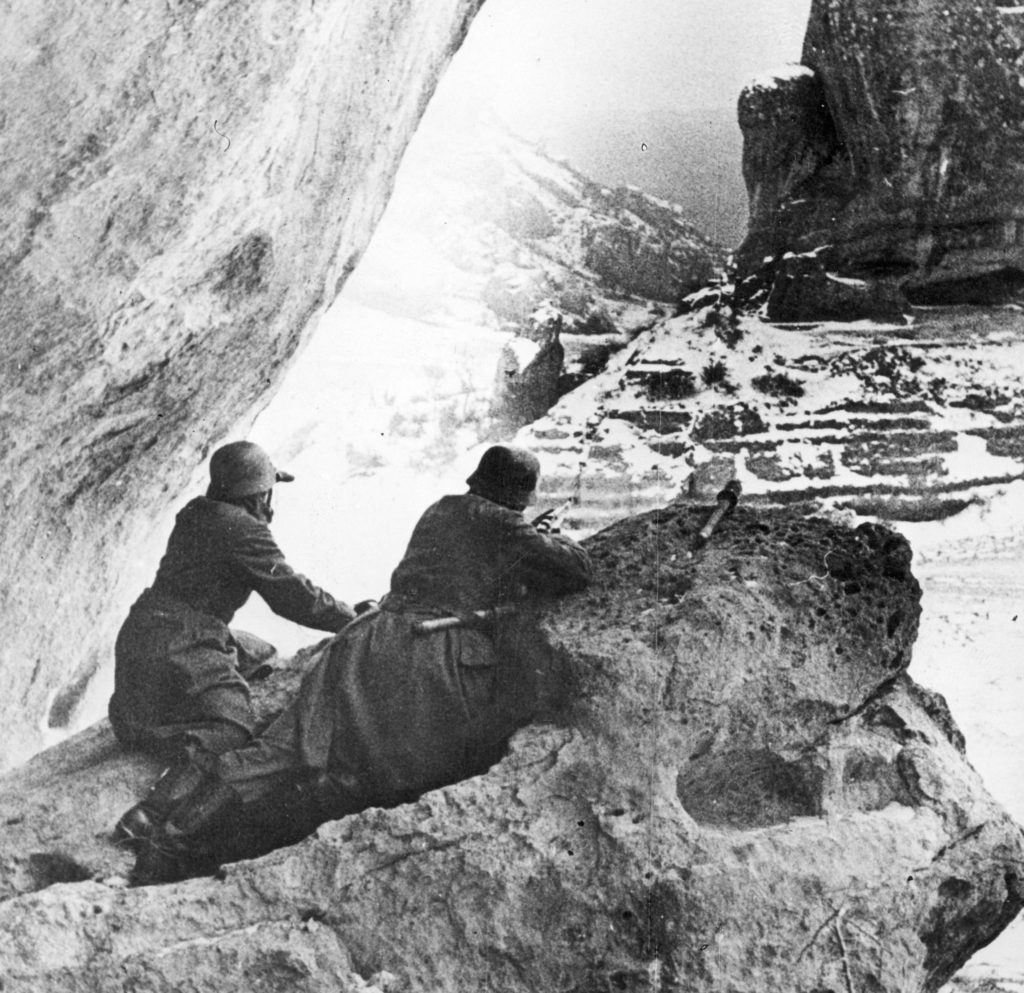

Nina went back into action during the Siege of Sevastopol. The Nazis punished the city with a campaign of unbridled violence to force a surrender. Yet the embers of defiance burned fiercely from underground tunnels and beneath the ruins of crumbled buildings.

“At first glance, Sevastopol looked deserted and lifeless. This was how the city appeared to the Nazi observers and pilots. But it rose to the occasion during moments of danger, exerting tremendous efforts and mustering enormous strength,” wrote Zoya Medvedeva, a fellow Red Army female soldier who became friends with Nina there.

“Fire issued from each and every rock … Thin smoke issued cautiously from under the ruins, from dugouts and covered trenches … The city was alive; it struggled and had no intention to surrender.”

The bloodied yet unbowed city of Sevastopol became a special place for Nina. She carried copies of Leo Tolstoy’s “Sevastopol Sketches.” The famed Russian author, who fought at Sevastopol during the Crimean War, examined the nature of sacrifices in war and pondered the meaning of heroism. Nina scribbled appreciative remarks into the margins, such as “How true!” or “I felt the same way!”

Nina became fond of a war song rallying courage for her native Crimea, entitled “The Sea Spreads Wide Near the Native Crimean Shores.” The rollicking, emotional tune was a favorite of the Chapaev Division and was usually sung by local men of the Red Army. She wrote down the lyrics and kept them with her.

Distinguished Service

As Nina made friends around the city, she taught others to be resourceful. She asked local factory workers trained to make pots and pans to craft spare parts for her machine gun in case of emergencies. She taught others how to quickly strip down and reassemble their weapons.

A colonel once challenged Nina to take apart and reassemble her machine gun while blindfolded in under a minute. “Onilova’s performance was brilliant,” Zoya wrote in a postwar memoir entitled “My Fire-Scorched Youth.”

“Onilova was so quick in stripping and assembling the breech-block [of her machine gun] that it took our breath away,” Zoya remembered. “Then she told us how she selected reference points for aimed fire both by day and night.”

On Nov. 21, 1941, Nina was near the village of Mekenziya near Sevastopol when she had a one-on-one duel with a German tank. Nina crawled alone across a 65-foot expanse and set fire to the tank with two Molotov cocktails.

For her courageous action, General Ivan Yefimovich Petrov decorated her with the Order of the Red Banner, and she was promoted to the rank of sergeant.

Inspiring Women

Nina encouraged her best friend, Zoya, to pursue becoming a machine gunner too despite the chafing of soldiers around them.

“Like all defenders of Sevastopol, I was very fond of Nina, a simple and merry young girl, yet a bold and brave soldier,” Zoya said years later. “I dreamed of transferring to Onilova’s unit and becoming No. 2 of her machine gun crew.”

Nina was so persistent in lobbying for a fellow woman to take up the machine gun that eventually the Chapaev Division’s commander, Colonel Nikolai Zakharov, agreed. He decided to make a festive occasion of it despite the bitter hardships of war. He said he would promote Zoya and throw a party for both girls on the same day.

“This will be my gift … on the occasion of International Women’s Day, March 8, which is rapidly approaching,” Zakharov said. “So you, Nina, must join us without fail in celebrating the holiday. We’ll treat you to cherry jam and tea, served in a genuine cup and saucer, rather than an aluminum mug.”

“All right, Comrade Colonel!” replied Nina with an enthusiastic smile, according to Zoya. It was the last time they saw Nina alive.

Final Battle

On Feb. 28, 1942, Nina and her crew were overwhelmed by enemy forces during a night battle near Mekenziya. Destroying two enemy machine gun nests, Nina kept fighting after the rest of her crew was killed. Staying behind to provide covering fire for retreating Soviet forces, Nina was quite literally the last soldier left defending the area when an enemy mortar blast struck. She received fatal injuries to the chest.

According to testimony by Soviet reporter Aleksandr Khamadan, present at Sevastopol during the siege, Nina did not die instantly. Red Army soldiers managed to rescue her. She was transported to an underground hospital within the Inkerman caves near Sevastopol.

Khamadan visited Nina at a makeshift hospital room in a cave hollowed from rock and lit by an electric bulb. Nina faded in and out of consciousness and occasionally tried to speak. A medical official named Varshavskiy who spoke with Khamadan said: “We are doing everything modern medicine is capable of, but she has been wounded too many times and has lost too much blood.”

Last Letter

Shortly before her death, Nina’s thoughts had returned to the beginning of her journey. Among the last things she did was write to Varvara Myasnikova, the actress who had played her heroine, Anka. Nina tried to explain that Myasnikova’s performance had sparked the fierce determination that had brought her to this point.

“I am unfamiliar to you, comrade, and you will excuse me for this letter. But from the very beginning of the war, I wanted to write to you and get to know you,” she wrote. “I know that you are not that Anka, not a real Chapaev machine-gunner. But you played like a real one, and I always envied you. I dreamed of becoming a machine gunner and fighting bravely as well.”

Although her relentless pursuit of soldiering had brought Nina to her eventual death, she expressed no regrets. “When you defend your dear, native land and your family … then you become very brave and do not understand what cowardice is,” Nina went on in her letter. She tried to go on to describe her fights. “I want to tell you in detail about my life,” she wrote. But her letter was left unfinished.

Red Army commander Ivan Yefimovich Petrov, the same general who had decorated Nina with the Order of the Red Banner months earlier and who was leading the defense of embattled Sevastopol, came to visit her and attempted to comfort her in her last moments.

“Well, little daughter, you fought gloriously,” Petrov told her, stroking her head as she died. “Thank you on behalf of our entire army and our entire nation …. Everyone in Sevastopol knows about you. The entire country will learn about you, too. Thank you, little daughter.”

Legacy

Nina died on March 8 — which, in a strange stroke of fate, was also observed by the USSR as International Women’s Day. She was supposed to meet her best friend Zoya, her commanding officer Zakharov, and other soldier friends that day for a small gathering. They had prepared cherry jam and tea.

Instead, the group received a telephone call that day informing them that Nina had died. Since nobody had notified them that Nina had been wounded days earlier, the news came as a complete shock. The soldier who answered the phone reacted with disbelief. “Nina! We are expecting her. We’ve prepared gifts for her,” he said.

“I was there in the dugout. I heard what was being said about Nina and I didn’t believe it,” Zoya wrote. “I cried and I didn’t believe it. But it was true.”

That same day Zoya took up Nina’s proverbial sword as second-in-command of a machine gun crew. But this wasn’t enough for Zoya — unable to visit Nina in the hospital, she instead visited her friend’s gravesite at Sevastopol’s Communards cemetery, where she swore to avenge her death.

Zoya went on to command several machine gun platoons in battle. She was badly wounded several times and partially lost her eyesight due to her injuries. She escaped the fall of Sevastopol and remained on active service until the fall of 1944, achieving the rank of senior lieutenant. She survived the war.

“There were people near me whom I respected and loved with all my heart, and whom I’ll never forget,” Zoya wrote in the conclusion of her postwar memoir as she reflected on Sevastopol and friends who lost their lives. “And when we recall those whom we loved, to us they seem eternally alive.”

Others who played a role in Nina’s life story met with tragic fates. Zakharov, who had arranged the party for Nina, was killed in June 1942. Khamadan, the reporter who visited Nina in the hospital, was later taken prisoner by the Germans after the siege and killed in captivity. The actress Myasnikova who portrayed Anka the machine gunner lost her mother and brother during the Siege of Leningrad. Petrov, present at Nina’s death, lost his battle for Sevastopol and attempted to shoot himself while being forced to evacuate, although he ultimately survived the war.

Nina and Zoya made history. According to Marshal of the Soviet Union Nikolai Ivanovich Krylov, chief of staff of the Independent Coastal Army during the war, the two were the only female commanders of machine gun crews to defend Sevastopol or Odessa. Nina was recognized as a Hero of the Soviet Union on May 14, 1965.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.