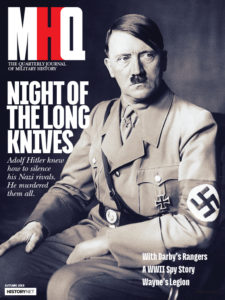

Adolf Hitler needed Ernst Röhm and his storm troops to climb to power in faction-torn Germany. Then came the day he didn’t need them anymore.

IN THE CHILLY DAWN OF JUNE 30, 1934, TWO BLACK MERCEDES-BENZ automobiles wound their way around the misty western edge of Tegernsee Lake in the rolling Bavarian foothills roughly 30 miles south of Munich. The picturesque countryside had been a favorite vacation spot of weary city dwellers since the late 19th century, but the occupants of the dust-trailing vehicles were not going on vacation—far from it.

The man in the passenger seat of the lead car, pale faced and puffy eyed after more than 24 hours without sleep, sat silently, glowering, arms folded impassively across his chest. He had lowered the window to let in a reviving breeze. His name was Adolf Hitler, the duly elected chancellor of Germany, and he was in the midst of the biggest gamble of his career. If he succeeded, he would stand virtually unchallenged as the de facto ruler of Germany. (Only Paul von Hindenburg, the aged and essentially impotent president, outranked him.) If he failed, he faced the prospect of a full-blown revolt by three million street-fighting thugs he had brought up alongside him in his 15-year rise to power. The stakes could not have been higher—a fact Hitler, a compulsive gambler, knew only too well.

Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, jabbered incessantly from the backseat of the car. The ferret-faced Goebbels was doing what he did best: twisting, parsing, and mauling the truth. His subject this morning was the black-hearted perfidy of Hitler’s closest ally and perhaps only personal friend: Ernst Röhm, the barrel-chested, battle-scarred commander of the Sturmabteilung (SA), the private army within an army whose members across Germany in fearsome brown shirts and black leather jackboots. Goebbels ranted on, but Hitler tuned him out. He had already made up his mind about Röhm. He didn’t need Goebbels to tell him what to do.

The SA, like Hitler and the metastasizing Nazi Party it served, had come to power in the streets of postwar Munich, springing from the ruins of the Imperial German Army. The first official storm troop unit was formed in 1915 to test experimental weapons and develop new tactics to break the deadly stalemate on the Western Front of World War I. Commanding General Erich Ludendorff soon ordered all German armies in the west to form their own battalion of storm troops. During the last-gasp Ludendorff Offensive in March 1918, SA storm troops spearheaded an initially successful breakthrough before the startled Allies, with decisive help from the newly arrived American Expeditionary Forces, could stabilize their lines.

Oddly enough, the man who would come to be most associated with the SA, Munich-born Röhm, was not an original storm trooper but a twice-wounded army staff officer. When the war ended, he was serving behind the lines, still recovering from a serious wound he’d received at the Battle of Verdun in 1916, when a bullet tore away the bridge of his nose and sliced a deep gash on his left cheek. Röhm’s SA debut would come not on the battlefields of western France but in the smoky beer halls and rubble-strewn streets of Munich, where a strident new voice belonging to an obscure Austrian war veteran was rallying ever-larger crowds. Hitler, like Röhm, held the Iron Cross First Class for bravery, but he’d chosen not to stay in the army after the war ended. His battle was elsewhere.

MUNICH WAS GROUND ZERO FOR THE MURDEROUS POSTWAR POWER STRUGGLE between Germany’s many contesting political groups. Hitler’s minuscule German Workers’ Party, on the far-right wing of the political spectrum, first attracted attention on October 16, 1919, when it held a public meeting in the city’s famous Hofbräuhaus beer hall. Only 70 people showed up, but a second meeting a month later drew twice that many—more than a few who came to harass Hitler and his cronies. When a scuffle broke out, the SA troops in attendance pitched into the fray, giving the hecklers bloody noses, bruised heads, and black eyes. Hitler, who didn’t miss much, quickly noticed his newfound allies.

Three months later, Hitler and the newly renamed National Socialist German Workers’ Party—Nazis for short—held another rally at the Hofbräuhaus. This time 2,000 people attended, including a number of SA members armed with rubber truncheons to intimidate any dissenters. After the meeting the SA formed a permanent Saalschutz Abteilung (meeting hall protection detachment) to provide security for future party gatherings. To avoid attracting the inconvenient notice of the government, Hitler renamed it the Gymnastic and Sports Division—an early indication of the Nazis’ cynical penchant for doublespeak. Members of the detachment began calling it the Sturmabteilung, after Germany’s elite World War I battalions.

In November 1921 the Nazis once again met at the Hofbräuhaus. Again a fight broke out, and again the SA made short work of the mostly Communist dissenters. “Not a man of us must leave the hall unless we are carried out dead,” Hitler instructed the 46 storm troops who were his personal bodyguard. Fists flew, bones crunched, boots stomped. The Reds were routed. Hitler, who had stood unflinchingly erect while dozens of beer steins whizzed past his head, looked on approvingly. Overnight, the sordid little barroom scrap assumed legendary proportions. In the parlance of another organized group of thugs—the Italian-born Mafia—the SA had “made its bones.”

Disaffected young veterans flocked to fill the SA’s ranks and stand at Hitler’s side as he traveled through Germany, speaking whenever and wherever he could, perfecting his standard stump speech—a dizzying farrago of grievance and denunciation of the Marxists, Communists, Bolsheviks, antinationalists, and peace-seeking cowards who had betrayed Germany in World War I and plunged the country into a devastating depression. Among the first rank of Hitler’s favorite villains were Germany’s Jews, many of whom had served beside Hitler in the stinking trenches of the Western Front, but who now were embarked, he claimed, on a secret mission to take over the world. The Jew, he said, was “a destroyer, a robber, an exploiter.” Only the pure at heart could stand against the insidious forces out to destroy Germany. The storm troops in the SA were the front line of defense. “He who today fights on our side cannot win great laurels, far less can he win great material goods,” Hitler warned. “It is more likely that he will end up in jail. He who today is a leader must be an idealist, if only for the reason that he leads those against whom it would seem that everything has conspired.”

Hitler would soon back his words with deeds. On November 9, 1923, he led a coup attempt in Munich against the Bavarian government, but the abortive Beer Hall Putsch—named for the drinking establishment stormed by Hitler and his followers—was a dismal failure. He and Röhm were among dozens of Nazis and SA members arrested for fomenting a failed rebellion. (Röhm’s troops had occupied the War Ministry for 16 hours, while Hitler and other SA followers had taken to the streets.) Hitler served nine months at Landsberg Prison, writing his manifesto, Mein Kampf, in his free time; Röhm was paroled and given a conditional discharge from the army. He spent his time raising a new force, the 30,000-member Frontbann, to replace the now outlawed SA. When Hitler was released, he quarreled with Röhm over the structure of the Frontbann, from which Hitler wanted unquestioning, obsequious service. Röhm, disagreeing, resigned from the group and withdrew from politics. Hitler, he complained to friends, “wants things his own way and gets mad when he strikes firm opposition on solid ground. And he doesn’t realize how he can wear on one’s nerves, doesn’t know that he fools only himself and those worms around him with his fits and heroics.”

In 1930 Hitler fired Röhm’s successor, Franz Pfeffer van Salomon, and asked Röhm to return from his self-imposed exile in Bolivia to become the newly reconstituted SA’s chief of staff. Röhm assumed command of a million-man army. Having learned his lesson—for a time—Röhm faithfully placed the SA at Hitler’s disposal, and it continued to fight street battles with Reds, intimidate and attack Jews, and rough up opposing journalists, university professors, politicians, local officials, and businessmen. At the same time, the SA showed a troubling propensity to believe its own revolutionary rhetoric, frequently siding with striking workers against conservative factory owners and their brutish strikebreakers. It emphasized the “socialist” and “workers” part of the National Socialist Workers’ Party and pushed for a “second revolution” against the forces of capitalism. Hitler, who needed the financial support of the same capitalists, demurred. “The revolution is not a permanent condition; we cannot allow it to become so,” he told party leaders in July 1933. “The unleashed stream of revolution must be guided into the sure channel of evolution.”

In case Röhm somehow missed the führer’s warning, Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick, one of Hitler’s oldest allies, was even more blunt and to the point. “The success of this undertaking will be seriously compromised if we continue to speak of ‘the next phase of the revolution’ or a ‘second revolution,’ ” Frick warned. “Anyone who continues to speak in these terms should get it into his head that by such talk he is in rebellion against the führer himself, and will be treated accordingly.”

Röhm, as always, was unbowed by criticism. “Those who think that the work of the SA is done must accept the idea that we are here, and that we shall stay here, whatever happens,” he told 80,000 SA troops massed at Tempelhof Airfield in Berlin in August 1933. “We must clean up the pigsty. Some pigs want too much; we’ll have to shove them back from the trough.” At a follow-up meeting three months later, Röhm renewed his threat to the status quo. “Many voices have been raised among the middle classes claiming that the SA has outlived its usefulness,” he thundered. “These gentlemen are very much mistaken. We will extirpate the old bureaucratic spirit of the petite bourgeoisie, with gentleness if possible, if not, without it.”

HITLER SOON FELT SECURE ENOUGH IN HIS CONTROL OF POWER to uncharacteristically thank Röhm for his service to the Nazi cause. In an apparently heartfelt letter dated December 31, 1933, Hitler praised “my dear chief of staff” for his role in “crush[ing] the Red Terror. It is above all thanks to you and your help that this political instrument became, within a few years, the force which allowed me to wage the final battle for power, and drive our Marxist adversaries to their knees. I must thank you, Ernst Röhm, for the inestimable services you have rendered to nationalism and the German people. You must know that I am grateful to destiny, which has allowed me to call such a man as you my friend and brother-in-arms.” The letter was released to the press.

Ironically, Hitler’s steady consolidation of power increasingly rendered the SA superfluous. With fewer political enemies to pummel in the streets, SA toughs resorted to fighting anyone who dared to look at them the wrong way. Fueled by long nights of drinking and debauchery, the storm troops frequently attacked unoffending passersby and then assaulted the policemen who rushed to their victims’ aid. Complaints of the SA’s “overbearing and loutish” behavior poured into Hitler’s office, and party newspapers published letters denouncing the open homosexuality of Röhm and many of his leading deputies. Of more concern to Hitler, who had known about Röhm’s sexual proclivities for years, was a report by the chief of the Gestapo, the much-feared political police, estimating that as many as 70 percent of the SA’s new recruits were former Communists drawn to Röhm’s continuing calls for radical revolution.

Röhm made other important enemies besides greedy capitalists, chief among them the aristocratic leaders of the Reichswehr, the standing German army, which by now vastly outnumbered Röhm’s SA. “I regard the Reichswehr only as a training school for the German people,” Röhm told an astonished General Walther von Reichenau, chief minister of the army, in October 1933. “The conduct of war, and therefore of mobilization as well, in the future is the task of the SA.” Many leading Reichswehr officers, proud Prussian aristocrats who traced their bloodlines back to Frederick the Great, were alarmed and outraged by Röhm’s presumption of command. They were further rattled when Max Heydebreck, an SA leader in Rummelsburg, publicly denounced army leaders as “swine,” adding: “Most officers are too old and have to be replaced by young ones. We want to wait till Papa Hindenburg is dead, and then the SA will march against the army.”

With the 86-year-old Hindenburg obviously nearing death, Hitler began angling to succeed him as head of the German state. Although Hitler privately shared many of Röhm’s complaints against the army’s old guard—as a lowly corporal following officers’ orders in World War I, he had been wounded and badly gassed—he still needed the tacit support of the Reichswehr in the looming political power vacuum. And in April 1934 he secretly met with army leaders aboard the armored cruiser Deutschland. In exchange for the military’s support once Hindenburg died, Hitler offered to reduce the SA’s ever-growing strength and numbers, rein in Röhm’s ambitions, and personally guarantee the army’s continued primacy in national affairs. He forced the reluctant Röhm to sign a pledge recognizing the Reichswehr’s supremacy in military matters. Privately, Röhm assured his followers that he had no intention of taking instructions from Hitler or his Prussian masters. “What that ridiculous corporal said doesn’t concern us,” Röhm blustered. “If we can’t work with Hitler, we shall get on without him. Hitler is a traitor. We’ll have to send him on a long vacation.”

DEADLY NEW ENEMIES ALSO BEGAN MARSHALING AGAINST RÖHM AND THE SA. Nazi prime minister Hermann Göring took the initiative to transfer control of the Gestapo from Röhm to Heinrich Himmler, the deceptively mild-looking commander of the Schutzstaffel (SS). Himmler, along with his steely right-hand man, Reinhard Heydrich, began converting the SS from its initial role as Hitler’s personal bodyguard into an independent intelligence-gathering organization. Himmler and Heydrich then assembled a phony dossier alleging that Röhm was plotting a coup against Hitler and had received 12 million marks from France for that purpose. While continuing to pledge loyalty to Röhm, Himmler drew a clear distinction between the SA and the SS. “The SA are the common soldiers,” he said. “The SS is the Elite Guard. There is always an Elite Guard. The Persians had one, the Greeks, Caesar, Napoleon and old Fritz. For the New Germany the SS is the Elite Guard.” Himmler understood better than anyone that such an elite unit needed ready-made enemies to justify its own existence. Röhm, with his unremitting calls for renewed revolution and three million hard-knuckled storm troops at his side, was the perfect target.

On June 4, 1934, Hitler made one last effort to rein in—or ward off—his old comrade. Summoning Röhm to Berlin for a one-on-one meeting, Hitler shared Heydrich’s manufactured evidence of an impending SA coup and implored Röhm to stop causing trouble. Röhm claimed in his account of the meeting that Hitler had assured him that the reports were “partly untrue and partly exaggerated, and that moreover he would for the future do everything in his power to set things to rights.” An adjutant in the chancellery anteroom reported a much less congenial discussion. He recalled hearing the two men “bellowing at each other” during a contentious five-hour meeting. Following the meeting, Röhm announced that he would place the entire SA on a monthlong leave while he rested at Bad Wiessee “to fully restore my health, which has been severely impaired the last few weeks by a painful nervous complaint.”

With Röhm and his henchmen safely sidelined, Heydrich stepped up his efforts to convince Hitler that the SA chief was plotting a revolt. At the same time, he and Himmler began drawing up a list of enemies of the state, both inside and outside the SA, who would have to be eliminated. They passed along secret orders to SS commanders to place their troops on “unobtrusive alert,” ready to act at the first word from SS headquarters. Within hours, word had flown through regular army channels as well, and Reichswehr troops were also placed on standby for imminent action. Hitler, conveniently, was away from Berlin, attending the wedding of a minor party functionary in Essen. “I had a feeling,” wrote fellow wedding guest Viktor Lutze, an erstwhile Röhm supporter who had switched his allegiance to Hitler, “that it suited certain circles to aggravate and accelerate the affair just at this moment when the führer was absent from Berlin and could therefore neither see nor hear anything himself, but was dependent on the telephone.”

As if on cue, Hitler received a call at the wedding reception. Göring, perhaps expecting the call, went with him. At the other end of the line was Himmler, who read off a series of new and alarming reports concerning alleged SA preparations for a coup, scheduled to begin at 5 p.m. the next day in Berlin. Göring nodded along, as if he could hear—or already knew—what Himmler was saying. “I’ve had enough,” Hitler said, putting down the phone. “I shall make an example of them.” He directed Göring to return immediately to Berlin and be prepared to act as soon as he received the code word: kolibri (hummingbird).

Then Hitler phoned Röhm at Bad Wiessee to complain about a comparatively minor incident involving rowdy SA troops and a foreign diplomat. Such behavior could not be tolerated, Hitler said, telling Röhm that he wanted to address a gathering of SA leaders at Bad Wiessee two days later at 11 a.m. Remarkably, Röhm was pleased to hear this. He told friends that Hitler’s visit would give him an opportunity to reassure his old comrade in arms of the SA’s continuing loyalty. He even arranged a luncheon banquet with special food for the vegetarian Hitler.

Hitler, outwardly calm but inwardly furious, dutifully followed through with a planned schedule of visits to local youth camps before he checked into the Hotel Dreesen at Bad Godesberg. Meanwhile, an old World War I colleague of Röhm’s, General Ewald von Kleist, made an 11th-hour visit to Reichswehr commander in chief Werner von Fritsch in Berlin. Kleist desperately tried to convince Fritsch that Röhm was not planning a coup. Himmler, he said, had set the SS and the SA at each other’s throats; Röhm was only reacting to Himmler’s threats. “That may be true,” responded Fritsch’s security officer, Prussian-born Walther von Reichenau, “but it’s too late now.” Himmler, manning his desk around the clock, was more succinct. “Röhm is as good as dead,” he said.

BACK IN HIS HOTEL ROOM, HITLER RECEIVED A SERIES OF WELL-CHOREOGRAPHED TELEPHONE CALLS Back in his hotel room, from Himmler and other plotters, each more alarming than the last. Himmler told him that Karl Ernst, Röhm’s longtime assistant, had arrived in Berlin to direct the SA’s seizure of key government buildings. From Munich, Bavarian gauleiter Adolf Wagner reported that SA storm troops were thronging public squares, shouting, “The Reichswehr is against us!” A mysterious pamphlet, probably created and distributed by the SS, enjoined SA members to “take to the streets, the führer is no longer for us!”

“It’s a putsch!” Hitler shouted. He summoned Major General Josef “Sepp” Dietrich, the head of Hitler’s handpicked 200-man bodyguard, and ordered him to fly at once to Munich, assemble his men, and head for Bad Wiessee. In the meantime, Hitler would also fly to Munich and direct events on the ground. “This is the blackest day in my life,” he told subordinates. “But I shall go to Bad Wiessee and pass severe judgment.” Operation Kolibri was underway.

Arriving at Munich’s Oberwiesenfeld Airfield just as dawn was breaking on June 30, Hitler was escorted to the Bavarian Interior Ministry by two armored cars and a truck packed with SS troops. He had not slept all night. Marching into the building with his heavily armed entourage, Hitler confronted Munich’s chief of police, August Schneidhüber, the highest-ranking SA member left in the city. Half asleep, Schneidhüber sprang to attention and began to salute Hitler, who rushed toward him, fists clenched, and shouted, “Lock him up!” Now in his familiar state of agitation, Hitler paced the hallways, pointing to one lower-ranking member after another and shouting for them to be arrested as well. “Traitors!” he screamed. “You will be shot!”

Hitler rejoined his motorcade and set out for Bad Wiessee. Meanwhile, other cars began leaving SS headquarters, dispersing across Munich and other cities across Germany. Himmler and Heydrich silently watched them drive away.

Hitler, exhausted, remained quiet during the 40-minute drive south to Bad Wiessee, rousing himself only to tell a young Reichswehr officer in the backseat that his colleague, General Kurt von Schleicher, was going to be arrested for suspected contact with Röhm and “a foreign power”—presumably France. The officer wisely said nothing. Of the eight men and one woman (Christa Schroeder, Hitler’s private secretary) traveling with Hitler, only Joseph Goebbels spoke, babbling incessantly about Röhm and the SA. Just outside Bad Wiessee the motorcade was joined, as arranged, by a truckload of SS troops led by Sepp Dietrich.

No one heard the cars drive into the courtyard at the Hotel Kurheim Hanselbauer. Even before they had come to a stop, armed SS officers leaped down and fanned out across the driveway, silently directing their troops into position. In the distance, church bells were summoning the faithful to early-morning mass. Inside the hotel, SA leaders were sleeping off a long night of drinking and revelry. Röhm, who had gone to bed early (and alone) after receiving a tranquilizer injection, was in a room on the second floor. The ground floor was deserted, the banquet hall already set for the midday feast to honor Hitler.

Outside Röhm’s room, Hitler, armed with a pistol, banged on the door. Röhm demanded to know who was there. “Adolf Hitler,” came the reply. “What? You’re here already?” Röhm said, groggily opening the door. “Ernst,” said Hitler, “you are under arrest.” Röhm began protesting, but Hitler spun away and began pounding on the next door until Röhm’s sleep-rumpled second in command, Edmund Heines, warily opened it. Behind him stood an 18-year-old storm trooper who had spent the night with him. When Heines resisted arrest, an SS soldier knocked him to the ground. Seeing his old SA colleague Viktor Lutze looking on, he cried, “Lutze, I’ve done nothing! Can’t you help me?”

“I can do nothing,” Lutze replied.

SS troops went from room to room, arresting other SA officers, many of whom, like Heines, were sleeping with younger storm troopers. The prisoners, including a half-dressed Röhm, were herded into a basement laundry room to await transfer to Munich’s Stadelheim Prison. A last-minute hitch arose when a truckload of heavily armed SA troops—Röhm’s personal bodyguard—suddenly drove into the courtyard where Hitler, Goebbels, and the others were standing. The troops were arriving for the banquet and were not surprised to see the führer waiting for them. They were surprised, however, by the SS soldiers aiming rifles and Lugers at them. A brief standoff took place; Operation Kolibri hung in the balance. Hitler, thinking quickly, ordered the SA men to return to Munich. “On your way,” he added casually, “you will meet SS troops and they will disarm you.” After a momentary hesitation, the men obeyed; with Röhm and their other commanders locked away in the laundry room, they had no reason not to. As Hitler reminded them, he was, after all, their führer.

With the meek departure of his bodyguard, Röhm’s fate was sealed. As Röhm and his fellow prisoners were loaded on two commandeered buses headed for Munich, Hitler, too, left Bad Wiessee. In another spur-of-the-moment decision that seemed in retrospect almost operatic in symbolism, Hitler decided against returning to Berlin and went instead to SA headquarters, the infamous Brown House, in Munich. There he had Goebbels telephone Göring with a one-word message: “Kolibri.”

The Night of the Long Knives, as the operation would come to be called, had begun.

ACROSS MUNICH, BERLIN, AND OTHER SELECTED LOCATIONS, SS murder squads fanned out in search of the victims on Himmler’s hit list. To avoid attracting attention, the squads were kept small—two to five men each. There was no need for more men; their unarmed victims weren’t expecting them anyway. Because of a hasty order from Hitler to immediately destroy all records of their actions, only the most prominent of the purge’s victims are known: General Kurt von Schleicher and his wife, Elizabeth, shot dead in their home on the outskirts of Berlin; Dr. Erich Klausener, director of the Ministry of Transport, killed in his home in Berlin; General Ferdinand von Bredow, Schleicher’s top assistant, gunned down on his doorstep in Berlin; Gustav von Kahr, a key prosecution witness in Hitler’s 1924 treason trial, hacked to death with pickaxes in a swamp near the newly opened Dachau concentration camp outside Munich; Father Bernhard Stempfle, a family friend of Hitler’s, shot three times through the heart after his neck was broken, found in a forest near Harlaching; Herbert von Bose, aide to Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen, shot 11 times at his desk in the ministry building in Berlin; Gregor Strasser, brother of Hitler’s arch political rival, Otto Strasser, shot dead in a cell in the Gestapo prison in Berlin as Reinhard Heydrich looked on. “Isn’t he dead yet?” Heydrich asked. “Let the swine bleed to death.”

Most of Kolibri’s victims were executed at Stadelheim Prison in Munich. At Hitler’s order, Sepp Dietrich personally supervised the executions, which took place, four at a time, in the prison courtyard, beginning with SA members Edmund Schmidt, Hans von Spreti-Weilbach, Hans von Heydebreck, and Hans Hayn. Outside each man’s cell, Dietrich stood and bellowed the same fatal message: “The führer has condemned you to death for high treason. Heil Hitler!” At Cell No. 504, August Schneidhüber, whom Hitler had arrested mere hours before at Munich police headquarters, pressed his face against the bars. “Comrade Sepp!” he cried. “This is madness. We are innocent.” Wordlessly, Dietrich moved on to the next cell. The executions continued every 20 minutes throughout the day.

At Lichterfelde Barracks, 20 miles southeast of Berlin, another 150 SA members were thrown into a cellar at the cadet school. As in Munich, men were brought out four at a time to be shot. In full view of his fellow captives, each man was led before a red-brick wall in the school courtyard, his shirt was ripped off, and a circle drawn with charcoal around his left nipple before a squad of eight SS sharpshooters blasted away at a killing range of five or six yards. The executions were so brutal that the unnerved firing squads had to be changed frequently. At his desk at Gestapo headquarters, the punctilious Heydrich tirelessly fielded telephone calls reporting the progress of the executions and filled out index cards bearing each victim’s name and fate: “arrested,” “in process,” “shot.” These he forwarded to Himmler and Göring.

In all, as many as 1,000 “enemies of the state” were killed in Operation Kolibri. One of the last victims, perhaps appropriately, was Ernst Röhm. For two days Hitler vacillated over his old comrade’s fate. He was inclined at first to spare him, but his malign hive of advisers—Göring, Goebbels, Himmler, and Heydrich—eventually wore him down. In the midst of a grotesquely ill-timed tea party in the garden of his Berlin chancellery, Hitler excused himself to phone the Interior Ministry. Theodor Eicke, the commandant of Dachau concentration camp and the de facto leader of the executions in Munich, answered the phone. Röhm was to be offered the opportunity to kill himself, said Hitler. If he refused, Eicke knew what to do.

Eicke grabbed SS officer Michael Lippert and hurried to Stadelheim Prison. Proceeding to Cell No. 474, they found Röhm, sweating and stripped to the waist, slumped on an iron cot. “You have forfeited your life,” Eicke told him. “The führer gives you one more chance to draw the right conclusions.” He placed a pistol loaded with a single bullet on a table in the cell. Fifteen minutes later Eicke and Lippert returned. Röhm stood in the center of the cell. “If Adolf wants to kill me,” he said, “let him do the dirty work.” Opening the cell door, Eicke shouted, “Röhm, make yourself ready!” Lippert, his hand shaking, fired two bullets into Röhm’s chest, then a third after he had slumped to the floor. “Mein führer, mein führer,” Röhm gasped. “You should have thought of that earlier,” Eicke replied, dismissing Röhm’s dying pledge of loyalty. “It’s too late now.”

Soon, it would be too late for millions. In one fell swoop, Hitler had eliminated his chief competitor, enlisted the nation’s most illustrious military and civilian leaders in his blatantly illegal cause, and served notice that, after Kolibri, no one was safe from the reach of the SS and its gunmen. When the 87-year-old Hindenburg died of natural causes conveniently one month later, Hitler became führer in fact as well as in name. The world was about to enter its own night of the long knives.

A disillusioned young SA officer who survived the purge, Werner Naumann, later summed up the events of June 30–July 1, 1934, for Hitler biographer John Toland. “The Röhm affair,” Naumann said, “was important to the development of the Third Reich, because here for the first time we had an unlawful, illegal action, one sanctioned by the Reichswehr, as well as the entire bureaucracy and legal body of the nation. It was totally unlawful and illegal, and nobody stood up to say, ‘So far and no further.’ Not even the church. And none of these groups could say they knew nothing about the matter. Everyone knew what had happened. And, in my opinion, this was the beginning of the end, because from now on the move was from the lawful and legal to the illegal and unlawful, and from now on there could be no turning back the clock.”

For Ernst Röhm and the numberless millions of future victims of Hitler’s now unstoppable rise to power, the clock had struck midnight. The hands were frozen at 12. MHQ

Roy Morris Jr. is the author of eight books, including, most recently, American Vandal: Mark Twain Abroad (Harvard University Press, 2015).

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2018 issue (Vol. 31, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Night of the Long Knives

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!