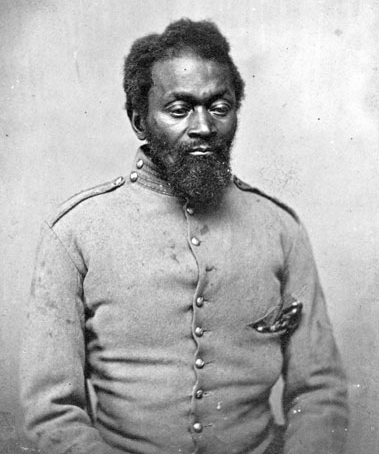

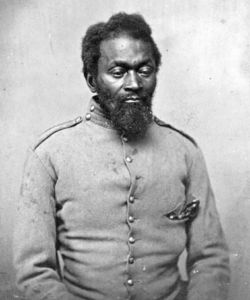

“N—— in Uniform! N—— in Uniform!” screamed the agitated Baltimore crowd of Southern sympathizers. They had been angry enough when Pennsylvania militiamen had detrained at Bolton Street station and began marching down Eutaw Street toward Camden Station on April 18, 1861, but when they saw Nicholas Biddle, an African American in uniform who was treated as an equal by his white comrades, their blood lust only increased and their calls grew louder. “Poor Nick had to take it” as the mob closed in like “wild wolves,” Captain James Wren, Biddle’s commander, later recorded.

Biddle soon was the target of more than just oaths, as salvos of bricks pried loose from the streets began to fly through the air. One struck Biddle in the head, knocking him to the ground and leaving a wound that reportedly exposed bone.

Many of the Pennsylvanians present that day believed Biddle was the first man to be struck down by an enemy combatant in the Civil War. Regardless of who shed first blood in what would be the bloodiest of all America’s wars, it seems strange that Biddle remains an overlooked and almost entirely forgotten figure in the Civil War’s rich history.

At the time, however, Biddle received the attention even of Abraham Lincoln as the president visited the militiamen being billeted at the U.S. Capitol on April 19. Lincoln wanted to thank the men who had arrived to defend Washington only four days after he called for 75,000 volunteers to quell the rebellion that began with the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12.

The president learned the Pennsylvanians had been attacked while traveling through Baltimore en route to the capital. Private Ignatz Gresser, a native of Germany, suffered from a painful ankle wound, and Private David Jacobs had a fractured left wrist and a few broken teeth. But it was the frail 65-year-old Biddle, wearing the uniform of the Washington Artillery, his head wrapped with blood-soaked bandages, who especially caught Lincoln’s attention. Biddle refused the president’s advice to seek medical attention, insisting that he preferred to remain with his company.

The Pennsylvanians were the first of the volunteers to arrive in the District of Columbia and would thus go down in history as the “First Defenders.” Their Baltimore injuries occurred as the men arrived for the final leg of their journey from Pennsylvania to Washington. The entire Baltimore police force had been summoned to escort the volunteers through the streets, but even the police had a difficult time controlling the raucous crowd of 2,000, which jeered the anxious militiamen while hurrahing for Jefferson Davis and the Southern Confederacy.

As the volunteers arrived at Camden Station, they were pelted with stones, bricks, bottles and whatever else the local mob could reach; some were even clubbed or knocked down by a few well-landed punches. A few bolder Confederate sympathizers lunged at the unarmed Pennsylvanians with knives and drawn pistols. First Defender Heber Thompson wrote that one man was caught dumping gunpowder on the floor of one of train cars “in the hope that a soldier carelessly striking a match in the darkened interior…might blow himself and his comrades to perdition.” For the idealistic volunteers from Pottsville, Allentown, Reading and Lewistown, the ordeal quickly erased any romanticized notions of soldiering they might have had.

BIDDLE’S INJURIES WERE THE MOST SERIOUS, an irony considering he wasn’t technically a soldier since the Federal government would not muster him in because of his race. Biddle, however, had willingly marched off to war as the orderly of Captain Wren, the Washington Artillery’s commanding officer. He had been associated with the company since its formation in 1840 and was so highly regarded by the members of the unit that they considered him one of their own and issued him a uniform.

Little is known about Biddle’s life, except that he was born a slave in Delaware about 1796 and later escaped. But exactly when he slipped the chains of human bondage is not known. Nor is it known where Biddle first settled in Pennsylvania. One account has him settling in Philadelphia, where he possibly was taken in by abolitionists. He reportedly soon found work as a servant in the lavish home of Nicholas Biddle, the wealthy financier and longtime president of the Second Bank of the United States, whose name the escaped slave adopted as his own.

According to this account, Biddle, along with his servant, traveled to the Schuylkill County seat of Pottsville in January 1840 for a celebratory dinner at the Mountain House hotel in the nearby village of Mount Carbon. Along with 80 industrialists and capitalists, they celebrated the success of William Lyman’s Pottsville Furnace, the first in the United States to smelt iron by an anthracite-fired blast furnace continuously for 100 days. For whatever reason, the servant Biddle remained behind in Pottsville when his employer returned to Philadelphia.

Another story, perhaps more plausible, has the escaped slave settling in Pottsville itself and becoming a servant at the Mountain House hotel, where he was employed during the January 1840 dinner. If this is true, then, as Schuylkill County historian Herrwood Hobbs wrote, “something of financier Biddle rubbed off on him,” and he adopted the capitalist’s name.

Whatever the truth, by 1840 Biddle had made Pottsville his home, taking up residence in a modest dwelling on Minersville Street. He took an active interest in the city’s two militia companies, the National Light Infantry and the Washington Artillery, whose members he quickly befriended. When news of President Lincoln’s call to arms spread throughout the North in April 1861, both the National Light Infantry and the Washington Artillery were quick to tender their services. Departing Pottsville on April 17, 1861, they reached Harrisburg late that evening. The following morning, the two companies, along with the Ringgold Light Artillery from Reading, the Logan Guards from Lewistown and the Allen Infantry of Allentown, boarded the North Central Railroad and began their journey to Washington via Baltimore. Before setting out from the Pennsylvania capital, the soldiers of the five companies took the oath of allegiance and were all sworn in as soldiers of the United States. All of them except Nicholas Biddle, of course.

The term of service for the initial 75,000 Northern volunteers—including those in the ranks of the First Defender companies—was for three months, and in late July 1861, the soldiers were mustered out. But most of the First Defenders were quick to reenlist, this time “for three years, or the course of the war.” Almost to a man, the National Light Infantry became Company A of the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry, while most members of the Washington Artillery reenlisted into the ranks of Company B, 48th Pennsylvania Infantry, with James Wren remaining as captain. Nick Biddle, however, did not accompany Wren when the 48th left Schuylkill County in September 1861. He remained in Pottsville, still nursing the painful head wound he had suffered in Baltimore.

Biddle spent the rest of his life in Pottsville, performing odd jobs until he began to suffer from rheumatism. As he grew older and more infirm he couldn’t perform any labor. Despite being a wounded veteran, he could not draw a Federal pension because he had never mustered in. Impoverished in his final years, he walked the streets of Pottsville seeking charity.

Pottsville’s leading newspaper, The Miners’ Journal, appealed to the community for help.

“If poor old Nick Biddle calls on you with a document, as he calls it, don’t say you are in a hurry and turn him off, but ornament the paper with your signature and plant a good round sum opposite your name,” the paper implored. “Nick has been a good soldier and now that he is getting old and feeble, he deserves the support of our citizens.”

Nicholas Biddle died in his home on August 2, 1876, at the age of 80. Before he died, the proud figure claimed he had enough money saved up in the bank for a proper funeral and burial, but upon his death it was discovered that there was not a penny to his name.

The surviving veterans of the Washington Artillery and the National Light Infantry once again answered the call. Agreeing to pay for the costs, they arranged Biddle’s funeral, which took place just two days after his death. A large crowd gathered in front of Biddle’s home and then, as a drum corps played, began the solemn procession up Minersville Street to the “colored burying ground” adjacent to the Bethel A.M.E. Church.

AFTER THE SERMON AT THE CEMETERY, a number of uniformed First Defenders carried the simple coffin to the burial site and laid Nicholas Biddle to rest. The surviving First Defenders contributed $1 each to pay for a tombstone, upon which was inscribed:

In Memory of Nicholas Biddle, Died August 2, 1876, Aged 80 Years. His Was the Proud Distinction of Shedding the First Blood In the Late War For the Union, Being Wounded While Marching Through Baltimore With the First Volunteers From Schuylkill County 18 April 1861. Erected By His Friends In Pottsville.

On April 18, 1951, the 90th anniversary of the First Defenders’ famed march through Baltimore, the people of Pottsville dedicated a bronze plaque for the Civil War Soldiers’ Monument in Garfield Square. “In Memory of the First Defenders And Nicholas Biddle, of Pottsville, First Man To Shed Blood In The Civil War. April 18, 1861,” it reads.

Since that time, remembrance of Biddle’s role in the Civil War has faded almost to the point of oblivion, and, shamefully, his tombstone has been destroyed by vandals.

John D. Hoptak works as a ranger at Antietam National Battlefield. He is the author of First in Defense of the Union: The Civil War History of the First Defenders, and maintains a Web site on the 48th Pennsylvania at 48thpennsylvania.blogspot.com.

Read the poem “The Grave of Nick Biddle“, a stirring ode written in 1876 about April 18, 1861, the day “In Baltimore City, where riot ran high.”