[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he most trying events of history have often produced stirring and important art, and the Civil War was no exception. Out of that conflict arose French artist Paul Philippoteaux’s monumental cyclorama painting of the Battle of Gettysburg, which took more than a year to complete and was unveiled to wide acclaim in 1883. Re-creating the third-day assault popularly known as Pickett’s Charge, Philippoteaux came closer to capturing the chaos and intensity of the battle—literally coming from all sides in a 360-degree view—than arguably any other work of art since the war had ended. Veterans reportedly wept upon seeing it. It remains on view in a purpose-built gallery at Gettysburg National Military Park.

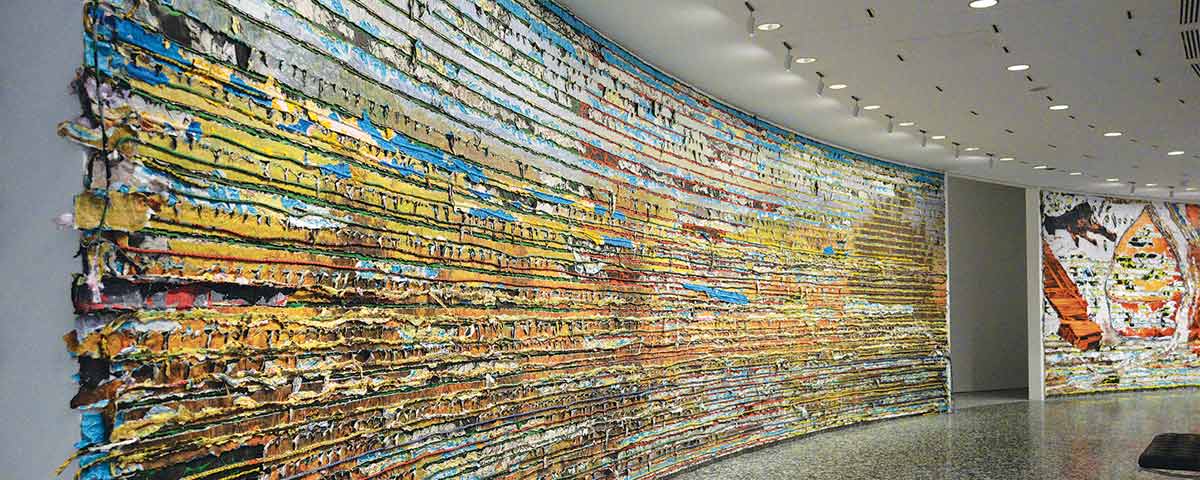

Philippoteaux’s work was and is important in part because it doesn’t romanticize the war. The painting beautifully depicts the Pennsylvania countryside, bathing it in a warm light, but the people in the painting are all marching, killing, bleeding, and dying. It is a difficult tableau. More than 150 years later, as many of us are still processing that painting, that battle, and that war, Los Angeles artist Mark Bradford has unveiled a provocative new work called “Pickett’s Charge,” on view at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Gallery in Washington, D.C., through November 2018. Commissioned specifically for the circular gallery, the artwork uses Philippoteaux’s work as the literal and figurative basis for a series of abstract panels—layered collages of paper and cord and glue, scored and ripped and sliced—that reflect our still-divided times. Sometimes, elements of the original painting can be seen clearly, sometimes not, and that’s the point.

Rather than one continuous circular panel, “Pickett’s Charge” features eight separate panels that tell a story moving nearly 400 feet in a clockwise direction around the gallery. With titles such as “Battle,” “The High-Water Mark,” “The Copse of Trees,” and “Dead Horse,” the pieces are each self-contained takes on some element of the original painting, but they aren’t to be taken literally. Strictly speaking, this is not “Civil War art.” Instead, the pieces invite contemplation of what the war has wrought on modern times, and the enduring nature of conflicts along racial and political dividing lines.

Bradford printed sections of the Philippoteaux painting from the internet, and when blown up, the bits of original painting that emerge are often fuzzy and pixelated, emphasizing past and present at once. “Battle” opens the series with a scraped and striated image that is difficult to make sense of—a maelstrom. In “Two Men,” one can make out the image of two soldiers, but the most striking aspect of the image are the evenly scored lines that make the wall resemble that of an old wood-framed house. The idea here is that what seems old is not really old; what seems over is not really over. “The High-Water Mark” originally referred to the Battle of Gettysburg itself—the high point of a string of victories for the South, the turning point of the war. Here, Bradford plays on the term with undulating, wave-like shapes and blue tones, emphasizing the fluidity of history, and of winners and losers.

“Dead Horse” is one of the most striking panels in the collection, featuring an image of a dead horse floating above the rest of the piece. Philippoteaux had painted a dead horse in a lane near the section of his painting that depicts General Meade’s headquarters, reflecting a gruesome reality for the civilians of Gettysburg after the fighting stopped, with dead men and dead animals strewn in the heart of their quiet town. Here, the dead horse echoes the old saying about something that is repeated ad nauseam, and to underscore the point, Bradford repeats several sections of the original painting in this panel. We see the same cavalry officer, the same marching soldiers, the same conflict, over and over again. It’s hard not to see current conflicts over race and gender as a repetition of the past as well, Bradford seems to be saying. In this panel, too, Bradford includes one of the largest identifiable images in the whole collection, which is a corn-yellow haystack blown up from the original painting. These stacks weren’t actually on the Gettysburg battlefield, but Philippoteaux clearly liked their shape and bucolic sensibility, and Bradford seems to as well.

In remarks posted on the gallery web site, Bradford says that “politically and socially, we are at the edge of another precipice. I’m standing in the middle of a question about where we are as a nation.” It’s a question that the Civil War tried to answer, and a question we’re still trying to answer. Thankfully art exists to help us talk about such things.

Based in Arlington, Va., Kim O’Connell writes frequently about history and preservation for a range of publications.