Journalism took pioneering female reporter undercover and around the world in 72 days

NELLIE BLY STARED into the mirror, working hard on looking mad. “I had read how crazy people have staring, far-away eyes so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinking at my own reflection,” she wrote later. “Wintery chills ran up and down my back in very mockery of the perspiration which was slowly but surely taking the curl out of my bangs.”

After four months in America’s newspaper capital without a nibble from a New York newsroom, the Pittsburgh-born Bly, at 23 a seasoned reporter, finally had pestered her way to a trial assignment. In September 1887 Bly had talked her way into the offices of the New York World and buttonholed the managing editor. John Cockerill called Bly’s bluff, proposing that she prove her mettle by going undercover as a patient on Blackwell’s Island, in the East River. The island was home to the Women’s Lunatic Asylum, a font of constant complaint about brutality and neglect. America’s 19th-century press occasionally covered asylums, but in a mild, insubstantial way. To get the real story, Cockerill said, Bly would have to get herself involuntarily committed and live for ten days as a mental patient. Bly took the dare. Later, when a colleague asked Cockerill exactly how he expected to retrieve his prospective reporter from the madhouse, the editor said, “I don’t know.”

Bly knew little about mental illness, but she knew how badly she needed and wanted a job. Giving her name as Nellie Brown, she moved into the Temporary Home for Working Women, a tall, dark boardinghouse set back from Second Avenue in the working-class Bowery. Bly set to ranting incoherently and behaving erratically; within a day fellow residents decided she was out of her mind. “I’m afraid to stay with such a crazy being in the house,” a resident told the landlady. Another said, “She will murder us all before morning!” Bly stayed up a second night, helped along by bloodcurdling screams from the next room and rats scampering across her pillow. Told later that the screams next door had arisen from a nightmare in which the dreamer imagined Nellie rushing at her with a knife, Bly said, “It was the greatest night of my life.”

Being tagged a loon was easy. Boarding house employees contacted the authorities. Policemen escorted “Nellie Brown” to court, where she spun a convincing tale, claiming her real name was Nellie Moreno, “a Cuban maiden of genteel Spanish lineage suffering from amnesia from an unnamed trauma that left her friendless and abandoned in an unforgiving city.” The judge, thinking Bly some fellow’s sweetheart gone astray, summoned the press; maybe a news story would alert the lost soul’s family. Fearful of being recognized, Bly covered her face and turned away, madly shouting, “I don’t want to see any reporters!”

The judge sent Nellie to Bellevue Hospital where medical experts concluded “Moreno” suffered from dementia and delusions of persecution. On September 26, she boarded a ferry bound for the asylum.

Unable to take notes, Bly memorized details, from the stifling, filthy ferry to the island’s screams and cries. En route she saw “two coarse, massive female attendants who expectorated tobacco juice about on the floor in a manner more skillful than charming.”

Blackwell’s Island, a 120-acre sliver, lies in the East River parallel to Manhattan and extending from 51st to 88th Streets; today it is known as Roosevelt Island. At the upstream end stood the Lunatic Asylum. Opened in 1839 as a state-of-the-art sanatorium for 1,076 patients, the facility, whose main building was known as the Lodge, now had more than 1,600 residents. As care costs grew, however, budgets for that care remained fixed.

In the 1800s, mental illness was a mystery; society viewed the mad as murderously violent or benign oddballs. Blackwell’s Island was a stop on an “asylum tourism” circuit. Gawkers, including Alexis de Tocqueville and Charles Dickens, visited asylums as they might zoos, bringing picnic lunches and commenting on how lucky residents were to inhabit such beautiful grounds. A Scribner’s Monthly entry for Blackwell’s promised “a pastoral experience.” The New York Times carried weekly picks of asylums’ most intriguing characters.

Bly had not come for the landscaping, but to see what really was going on, and she got an eyeful. Conditions were beyond disgusting: rancid food, foul water, forced feedings, fire hazards,

and patients tied down. “Witchy, vicious nurses choked, beat and harassed deluded patients,” Bly wrote. “I was forced to share towels with crazy patients who had the most vile eruptions all over their faces.” Shocked, Bly dropped her act. “The more sanely I talked and acted, the crazier they thought I was,” she later wrote. Attendants and guards saw just another girl gone mad.

She had to strip for a bath—three buckets of frigid water dumped on her head. “My teeth chattered and my limbs were goose-fleshed and blue,” Bly wrote. “The sensation felt as if I was drowning.” Dripping wet, she was shoved into a short cotton flannel slip emblazoned “Lunatic Asylum, B.I. H.6.,” for Blackwell’s Island, Hall 6. Attendants hurried her into a room with one bed whose mattress sloped steeply from the center. Bly asked for a proper nightgown. “We have no such things here,” an attendant said. “You are in a public institution. Don’t expect anything or any kindness here for you won’t get it.” The attendant locked Nellie in. Howls shattered the night. Bly learned the screamer, a pretty patient, had died. Nurses had beaten her, pinned her naked in a cold bath, and thrown her onto a bed. Cause of death: convulsions, doctors said.

Bly realized many fellow inmates were simply destitute immigrants. One woman’s heavily accented German, mistaken for gibberish, had led to a diagnosis of madness. A jealous Jewish husband had had his wife committed. When a chambermaid lost her temper, co-workers had her committed.

Bly strolled the grounds, where she saw attendants guarding patients walking two by two. Nurses accompanied a line of women, clad in similar strange dresses and comical straw hats and shawls, marching slowly and noisily. “They were cursing, yelling, singing and praying,” she said; the marchers were the most violent cases from the nearby Lodge. A rope looped through wide leather belts harnessed another 52 women to one another like mules pulling an iron cart holding a pair of invalids.

Missing girls’ relatives searched Blackwell’s for them. An unexpected gentleman caller nearly gave away Bly’s game. Summoned to the waiting room, she recognized a face familiar from Pittsburgh: George M. McCain, the Post-Dispatch man in New York. His editor had sent him to follow up on “Nellie Moreno.” McCain had talked his way onto the island by claiming to be searching for a female relative; an attendant was walking him around. “Don’t give me away,” Bly whispered. “No,” the other undercover reporter told the madhouse attendant. “This is not the young woman I came in search of.”

Cockerill kept his word, on day 10 sending attorney Peter A. Hendricks to spring “Nellie Moreno.” Bly went to work. The October 9, 1887, World feature section led with “Behind Asylum Walls,” two pages of tiny print. A week later “Inside the Madhouse” took readers onto Blackwell’s Island and into its inhabitants’ lives. “Born silly, Urene Little-Page was a 33 year old woman who she claimed she was 18 and would grow hysterical if contradicted,” Bly wrote. “Nurses would slap her face and knock her head causing Urene to cry more so they choked her then dragged her into the closet…The insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island is a human rat-trap,” she wrote. “It’s easy to get in, but once there it’s impossible to get out.”

Both editions sold out. Letters flooded the World newsroom. Stunt factor aside—until Bly, reporters rarely attempted so grand a deception, and few had produced so dramatic a narrative—Bly’s reporting presented not only shocking content but substantive allegations and evidence to support them. The island’s barred windows and locked doors were disasters in waiting. Tyrannical nurses choked, beat, and harassed patients. Food was rotten, utensils nonexistent. Patient upon patient used the same murky bath water. The asylum washed patient uniforms monthly. “Patients are injected with so much morphine and chloral they are made crazy,” Bly wrote. She testified about her observations before a grand jury.

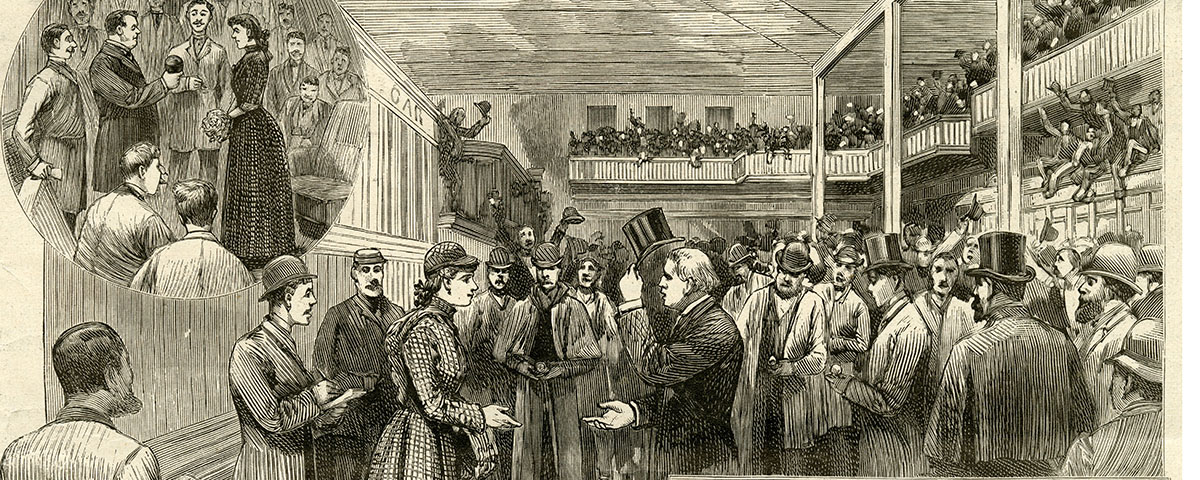

In response, Dr. Charles Simmons, head of the city’s charities and corrections board, invited New York City Mayor Abram Hewitt and the Board of Estimate to inspect the asylum. Bly joined that October 25, 1887, tour, by which time the asylum had cleaned up its act and fired incompetent workers. Cleanup or no, the jury recommended a million-dollar increase in the Department of Public Charities and Corrections budget for care of “poor unfortunates.” Changes Bly urged—transfer of foreign patients named in her reporting, better food and better staff, reduction of patient population, and installation of safety locks in case of fire—were made.

Nellie Bly had made her reputation.

Now she had to keep it.

John Cockerill hired Bly at $12 a week as a staff writer, and she became a newsroom star. For two years, she repeated variations on her nuthouse gimmick. Incognito as a maid, she exposed crooked employment agencies. Researching illicit trade in children, she bought a newborn for $10. She remained a notorious, if anonymous figure until, posing as a thief, she got herself arrested to investigate how women fared in New York City jails. Guards recognized her and gave her royal treatment.

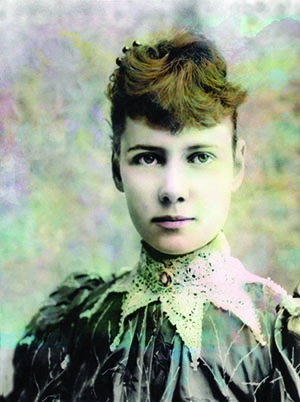

Bly was born Elizabeth Jane Cochran on May 5, 1864, into a blended family in Cochran Mills, Pennsylvania. Her father and the town’s namesake, Judge Michael Cochran, had brought to his second marriage 10 children from his first. Elizabeth was his 13th child—and his most rebellious, known as “Pink” for the girly shade her mother favored on her.

“She had great confidence,” Brooke Kroeger wrote in Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, and Feminist. “While everyone else dressed in drab brown and grays, she stood out in pink. Her mother taught her how to attract attention and revel in it. These were lessons that were never lost.”

Pink was six when Judge Cochran suddenly died. Her mother married an abusive drunk; Pink, 14, testified at the divorce hearing. After a semester of high school, she dropped out to help her mother run a boardinghouse in Pittsburgh. At 21, irked at a local newspaper columnist’s flippant essay on the theme “What Are Women Good For?” she wrote a blistering reply signed “poor little orphan girl.” Impressed, the paper’s editor offered her $5 a week as a reporter. As a byline, she chose “Nellie Bly,” a variant on the title of Stephen Foster’s 1849 song, “Nelly Bly.” She began working undercover. When stories like a sweatshop exposé got her reassigned to the society and gardening pages, she quit and left for Mexico, spending six months as a foreign correspondent. Bly’s articles on Mexican life were extremely popular but when she protested the arrest of a local journalist for criticizing the government, Mexican authorities threatened her with arrest. She headed to New York City.

From undercover work at the World, Bly moved to stunts. Since 1873, French novelist Jules Verne’s best seller Around the World in 80 Days and its quick-witted protagonist, Phineas Fogg, had fascinated readers. One night, skulling ideas, Bly exclaimed, “I wish I was at the other end of the earth!” The next day she pitched a real-world circumnavigation that would beat the fictional Fogg’s time. Her editors, who wanted to send a male reporter, resisted. The paper’s business manager explained how a man could travel the globe unaccompanied but not a woman, and that, like other female travelers, Bly would carry so much luggage as to defeat herself.

“Besides,” he mansplained. “You speak nothing but English!”

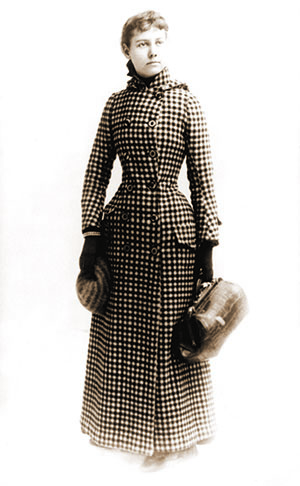

“Very well,” Bly said. “Start the man. I’ll start the same day for another newspaper and beat him!” The World caved. After a year’s planning, Bly, with £200 in British gold sovereigns and Bank of England notes, arrived on November 14, 1889, at a Hoboken, New Jersey, pier to board the Hamburg America Line steamship Augusta Victoria. The 112 pound, five-foot-five reporter sported a custom dress and a jaunty ghillie cap resembling Sherlock Holmes’s deerstalker, and, draping her neck to ankle, her trademark checkered Scotch ulster coat. She carried a 16-by-seven inch satchel.

Bly’s 24,899-mile journey—she saw it as a vacation, since she had been working for three years straight—was to carry her to London, the Mediterranean, Egypt, through the Suez Canal to Ceylon, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan, and over the Pacific to San Francisco, where the intrepid traveler would hop an eastbound train. Readers could ride with Bly in their heads; the paper was promoting an illustrated game and a pool guessing details of her arrival.

Bly had sisters in spirit writing for publications around New York. One was aristocratic Louisiana-born Elizabeth Bisland. Like Bly, Bisland had clawed her way off the society pages and into hard news and features. Tall and elegant, a published poet whose copy was more literary than Bly’s, Bisland, 25, had joined Cosmopolitan as an editor. Out of competition and to publicize his new property, Cosmo publisher John Brisben Walker went one-on-one with the World, dispatching Bisland the same day as Bly only six hours after pitching Bisland on the trip. She would travel west, recording her Christmas spent “steaming through the waters that wash the shores of the Indian Empire.”

Bly and Bisland moved by any means necessary, from luxury liner to burro to rickshaw to horse. Bly powered through monsoons, a smallpox scare, a five-day delay in Colombo, Ceylon, and, on the final leg, an encounter with a monkey, said to foreshadow bad luck. Not until reaching Hong Kong on Christmas Eve did Bly learn she had a rival. An official of the Occidental and Oriental Steamship Company told her Bisland had passed through three days earlier. Bisland kept that lead until she reached Southampton, England, where the German steamer Ems cast off without her, even though Cosmopolitan publisher Walker had bribed the shipping company to keep the liner at the dock until Bisland arrived. Bisland’s only option was a slow boat out of Queenstown, Ireland, that departed January 18 into “a storm-tossed North Atlantic in the worst weather that had been seen in many years.”

At Amiens, France, Bly called on 80 Days author Verne and his wife at their estate; Phineas Fogg’s creator encouraged his new friend to break his character’s record. Bly had become a commodity; trading cards, games, and other products bore her image. A hotel, a train, and a racehorse were named “Nellie Bly,” after the world’s most famous woman. Arriving in Jersey City, New Jersey, by train on January 25, 1890, at 3:51 p.m., Bly completed her trip in 72 days, six hours, 11 minutes and 14 seconds, beating the fictional Fogg. Elizabeth Bisland finished four and a half days later. After publishing a book, In Seven Stages: A Flying Trip around the World, the publicity-shy Bisland left the U.S. for a year among London’s literati.

Bly’s escapade had multiplied World circulation, but management proffered no bonus or raise. Bly resigned, embarking on a lecture tour; she earned $9,500—today, $250,000. She published Around the World in Seventy-Two Days, a printing of 10,000 copies sold out. Bly signed a three-year contract to produce serial fiction for New York Family Story Paper, earning $10,000 the first year and $15,000 the next two. In 1890, her brother Charles died. Nellie stepped in to care for her widowed sister-in-law and two children.

In 1893, a new editor took over the World Sunday features edition and persuaded Bly to rejoin the staff; the paper splashed the headline “Nellie Bly Again” on the front page. She covered a rail car workers’ strike against the Pullman Company, the fate of women in New York City jails and factories, and corruption among New York state legislators. She interviewed suffragist Susan B. Anthony and radical leaders Emma Goldman and Eugene V. Debs.

Bly often proclaimed no desire to marry but in 1895 she wed millionaire Robert Livingston Seaman. Seaman, 73, owned the Iron Clad Manufacturer Company, maker of milk cans, barrels, and other steel products.

Fans joked that she was only in it for the story, but Bly retired from journalism and began running her husband’s 1,500-worker factory and even patented a milk can design. After Seaman’s death in 1904, his widow became one of the world’s leading female industrialists, providing employees gymnasiums, libraries, and health care. She pulled the company’s fiscal chestnuts out of the fire by arranging refinancing.

In August 1914, Bly boarded the RMS Oceanic, bound for three weeks in Vienna, Austria. She stayed four years. When war broke out in Europe, she obtained press credentials.

Through the war the New York Evening Journal published “Nellie Bly on the Firing Line,” a column in which she revived the prose style of her scrambling days: “The ground was strewn straw. A mixture of senseless human beings, knapsacks, a flask, discarded bloody bandages, a shoe, a gun and matter unspeakable. One motionless creature had his cap on his head. Great black circles were around his sunken eyes. Black hollows were around his nose and his ears were black. Still he lived. Dying, I believe. I staggered out into the muddy road. I would rather look on guns and hear the cutting of the air by a shot that brought kinder death.”

Upon the signing of an armistice in November 1918, Bly returned home. She continued to write for the Journal and work to aid abandoned children and orphans. She died in 1922 of pneumonia at St. Mark’s Hospital in New York City. She was 57. Summing her up, an obituarist wrote that Nellie Bly “was the best reporter in America.” ✯