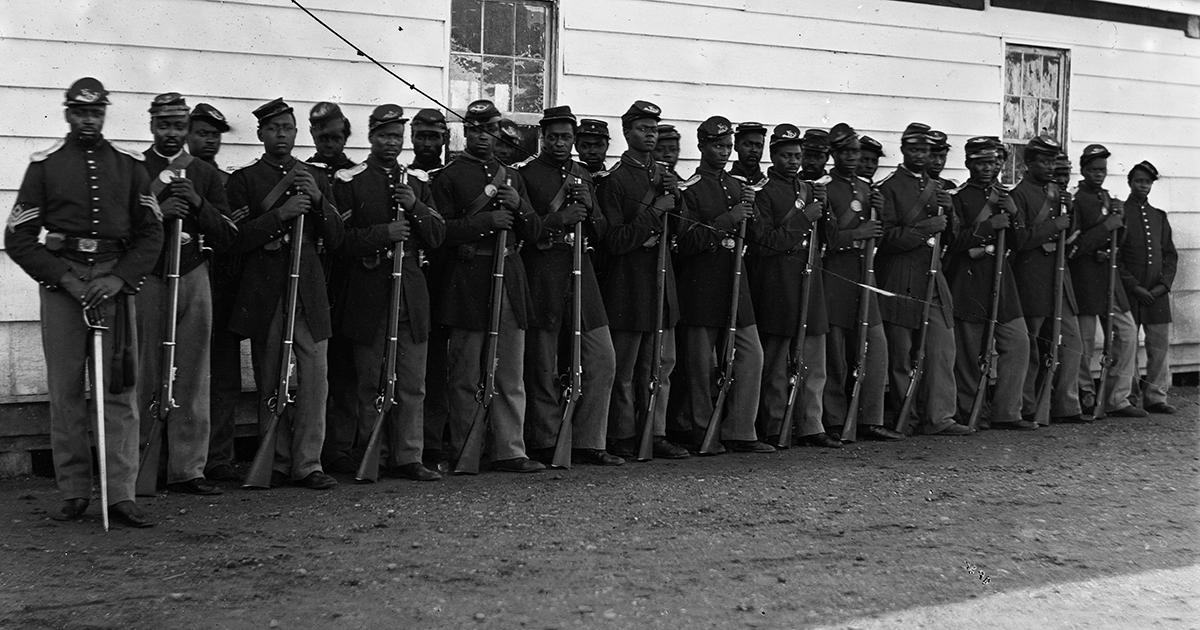

At New Market Heights, a Union general orders an attack that makes heroes and martyrs of his Black troops.

Some eight miles southeast of Richmond rises a short chain of hills. Known as New Market Heights, this high ground figured prominently in the defense of the Confederate capital. The open fields opposite the heights are hallowed ground in the saga of black soldiers in the Civil War. For on September 29, 1864, a short, furious battle was fought here that one Union general regarded as the ultimate test of the mettle of Black troops. They passed the test: afterward, fourteen Black soldiers who participated in the battle received the Medal of Honor for the valor they showed on that bloody day. During the entire course of the war, only two other Black soldiers received that honor.

The combat at New Market Heights was not the first for black troops in the Civil War, nor would it be the last. Its 800-plus casualties would make it the bloodiest of the war for Black troops save one: the Crater at Petersburg, where losses exceeded 1,300. Yet for all the heroism and sacrifice, the bitter truth remains that the ultimate justification for the fighting at New Market Heights was neither tactical nor strategic but political.

Here, Black men were ordered into harm’s way to prove to the white world that they could fight as soldiers. The victory won with their blood proved irrelevant to the larger strategic objective of cracking Richmond’s defensive ring. Adding to the tragedy, the operation’s architect became so obsessed with the fate of his Black troops that it effectively blinded him to nearby successes that, for a brief window of opportunity, opened the door to the Rebel capital.

New Market Heights represented one prong of a two-pronged strike at Richmond directed by a well-connected and controversial Union commander. Benjamin Franklin Butler was a political general who embraced cunning in lieu of West Point doctrine, and who substituted elaborately drafted battle plans for leadership.

Butler was New Hampshire-born, Massachusetts-raised. His first profession was law, but he soon set aside his lucrative work as a criminal lawyer for what proved to be an equally rewarding career in Bay State politics. Where he stood on the momentous issues of the day depended a great deal on when he was asked. He was a States’ Rights Democrat who tried to make Jefferson Davis his party’s presidential candidate, but settled on John C. Breckinridge. Once the war began, Butler veered over to Radical Republicanism in his support for a strong central authority.

He was among the first to rally to the flag when the shooting war erupted, leading the 8th Massachusetts Regiment to lift a blockade of Washington. He earned the grateful thanks of President Abraham Lincoln, who appointed Butler his first volunteer major general. After directing his command into thorough defeat at one of the war’s early small battles (Big Bethel), Butler managed to obtain a position as commander of the operation that captured New Orleans.

He ruled the city with an iron fist, leavened with his own peculiar standard of justice. Opportunism coexisted with public duty for Butler, so while he kept the peace in New Orleans, he also made certain that a large piece of the action came to him and his cronies.

When the outcry over this self-aggrandizement became too loud, Butler moved on to command a small army based at Fortress Monroe, on the tip of the Virginia Peninsula. This force, which he grandly proclaimed the Army of the James, was assigned a key role in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s grand military campaign of 1864. Butler, who had never before led soldiers into combat, sailed up the James River and landed with his troops on May 5, 1864, at Bermuda Hundred, a peninsula formed by the confluence of the Appomattox and James rivers.

Butler’s strategic objectives were to threaten Petersburg to the south and attack the presumably soft underbelly of Richmond, which lay only sixteen miles to the north. By the time this operation finally sputtered to a close less than a month later, Butler had achieved neither goal. Instead, he had allowed Rebel troops to pen up his army on Bermuda Hundred. They erected a formidable line of earthworks that stretched across the peninsula’s relatively narrow neck.

There, for the most part, Butler’s Army of the James remained while Grant’s Army of the Potomac fought its way through Virginia from the Wilderness to Cold Harbor. Then Grant shifted his focus from destroying Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to capturing the rail center of Petersburg. Doing so would render Richmond untenable. Other than holding his position on Bermuda Hundred, loaning out portions of his command when called upon by Grant, and launching some ineffectual stabs at Petersburg, Butler added little to his small collection of laurels as the summer of 1864 slipped toward fall.

Now stalled in front of practically impregnable earthworks before Petersburg, Grant began a series of “one-two” offensives. A Federal force would land on the north side of the James River near a place called Deep Bottom in order to threaten Richmond and compel Lee to strip his Petersburg garrison for reinforcements. Then, once Lee had committed himself, Grant would punch at the Rebel right flank below Petersburg. The first Deep Bottom expedition in late July had been paired with the Petersburg attack that became known as “the Crater.” A second Deep Bottom attack in mid-August mated with a corresponding thrust against the Weldon Railroad.

Both times the Army of the James had played minor supporting roles, leaving the spotlight to the Army of the Potomac. Grant was getting a new “one-two” offensive ready for September, but this time General Butler wanted to handle the northern part entirely with his own soldiers. Grant agreed, setting the stage for what would prove to be the most serious Federal effort to capture Richmond in 1864.

The four black infantry brigades were a key element in Butler’s Army of the James, a quarter of its total strength. Butler’s personal attitude toward these troops had undergone a dramatic change as the war progressed. Initially, he followed the line that this was to be a white man’s war, going so far as to offer the use of his Massachusetts troops to keep the slaves of “loyal” Maryland in line.

However, when Butler commanded the Fortress Monroe enclave, the sight of slaves being forced to construct Rebel earthworks incensed him. Putting his legal mind to the problem, he decided that if black slaves were indeed property, then he should be able to confiscate them as “contraband of war.” While the record is not clear whether or not Butler actually pioneered this concept (he claimed he did), his use of it made it possible for Federal officers to legally ignore the Fugitive Slave Act. According to one admiring writer, Theodore Winthrop in the Atlantic Monthly, Butler’s “contraband of war” policy was nothing less than an “epigram [that] abolished slavery in the United States….”

When he was commanding in New Orleans, where Confederate threats loomed larger than the paltry reinforcements he was receiving, Butler had pragmatically called up a number of Louisiana state militia regiments and added them to the Federal ranks, carefully ignoring the fact that several had only free black volunteers with black officers. By the time he reached Bermuda Hundred, Butler was not only a strong advocate for recruiting black soldiers but also for committing them to combat. He blamed widespread “prejudice and ignorance” for doubts expressed by whites, especially white politicians and military officers, “that the negroes would fight.”

Butler believed that this situation would not change until the black infantryman had a real opportunity to show “valor and…staying qualities as a soldier….Therefore,” he declared, “I determined to put them in position to demonstrate the fact of the value of the negro as a soldier…and that the experiment should be one of which no man should doubt, if it attained success.”

Butler was committing most of his 26,600-man army to an operation with the primary objective “to get possession of Richmond,” according to a detailed sixteen-page missive from his headquarters. Failing that, the Army of the James was to tie down as many Confederate troops as possible to prevent them from being shifted south to Petersburg, where the Army of the Potomac was about to launch a corresponding offensive.

To accomplish his objective, Butler planned to strike the strong Rebel defenses protecting Richmond with two heavy blows. Both Federal forces would cross the James River on pontoon bridges. His left wing, consisting of two divisions from the Eighteenth Corps under Maj. Gen. Edward O. C. Ord, was to cross the James at Aiken’s Landing, then attack the Confederate entrenchments guarding Richmond, especially Fort Harrison and Fort Gilmer. At the same time, the entire Tenth Corps plus a division from the Eighteenth, all under Maj. Gen. David B. Birney, were to emerge from the Union-held pocket at Deep Bottom and, in Butler’s words, “endeavor to carry Newmarket road and the heights adjacent….”

The Federals had tried the Deep Bottom approach before and, on those occasions, the formidable Rebel earth- works fronting New Market Heights had proved impossible to breach. Both of those expeditions had held Deep Bottom as a pivot point, then swung east and north, trying to flank the Confederate line. This time, the Union troops were going to hit the entrenched position head on. Butler’s extensive instructions specified that the attack would either be made by the 3rd Division of the 18th Corps (an all-black unit) or a division of the 10th Corps (one of three being all-black). Butler’s personal sentiments and strong advocacy on their behalf, and the fact that he massed his black units for the attack while deploying all white troops in flank support, made it clear that he wanted to showcase his black troops in the assault.

It could be argued that Butler’s determination to commit his black soldiers to combat blinded him to broader strategic opportunities. His left wing offered the best chance for cracking Richmond’s defensive ring and actually entering the Rebel capital. Yet Butler was committing more troops to his right wing (just over ten thousand men) than his left (fewer than eight thousand).

The right wing force that pressed across the Deep Bottom pontoon bridge on the night of September 28 consisted of six brigades of white infantry in addition to the four black ones. Only two of the latter would actually play an active role in the attack. All of the assault troops would come from Brig. Gen. Charles J. Paine’s Eighteenth Corps division (temporarily assigned to Birney). Of the three brigades in that command, the one led by Col. John H. Holman (1st, 22nd, and 37th United States Colored Troops, or USCT) would see almost no action, but the other two—Col. Samuel A. Duncan’s (4th and 6th USCT) and Col. Alonzo G. Draper’s (5th, 36th, and 38th USCT)—were slated for their toughest combat of the war. Bowing to the racial divide of the era, all field officers in these units were white, with the color line of the time stopping black men from rising beyond the rank of sergeant.

The position confronting them was naturally strong and stoutly defended. It was bordered by a strip of swampy ground, its stopping power enhanced by a belt of man-made entanglements (almost all of which were constructed by slave labor). Behind these defenses were some of Lee’s most experienced troops: Benning’s Brigade of Georgians, under Col. Dudley DuBose, and the famed Texas Brigade, now led by Lt. Col. Frederick Bass. Brig. Gen. John Gregg wielded overall command. Rounding out his force were two battalions of short-term men, six artillery pieces, and Brig. Gen. Martin W. Gary’s veteran cavalry brigade—perhaps forty-four hundred men in all. The Texas units especially had a reputation for showing black soldiers no quarter.

Sgt. Maj. Christian A. Fleetwood of the 4th USCT was a man of few words—at least where his diary was concerned. “Reg[imental papers] and knapsacks…packed away,” he wrote on the morning of September 29. “Coffee boiled and line formed.”

“We were all up at three o’clock, took our hot coffee and hard tack and started to [the] field, as the first streaks of dawn were appearing,” recalled Lt. Col. Giles W. Shurtleff of the 5th USCT, who had been briefed about the operation only a few hours earlier. “We were told that Grant would be with us, and that it was intended to push straight to Richmond.”

In the bustle accompanying the mustering of the 6th USCT, Capt. John McMurray found time to worry about a man in his company named Emanuel Patterson. The soldier looked sick and said he felt sick, but when McMurray tried to have him excused, the regimental surgeon pronounced him fit for duty. McMurray noted that Patterson “took his place in the company” as the regiment formed with the rest of the division.

At around four in the morning, General Butler rode among the troops he was knowingly sending into a hard fight. “I told them that this was an attack where I expected them to go over and take a work which would be before them…and that they must take it at all hazards, and that when they were over the parapet into it their war cry should be, ‘Remember Fort Pillow’ [a Confederate victory that April in Tennessee, where Union troops believed the Rebels had massacred a number of those who had surrendered, especially the black troops].”

“In contemplating since the results of that day,” Captain McMurray wrote in 1916, “I have been led to see the wisdom of God in concealing from man what is before him, as I never saw it before. Had I known when I arose that morning what was in store for my company, for my regiment, within the next two or three hours, I would have been entirely unfitted for the duties of the day.”

Then the advance began. “All the troops were in motion moving off in various directions to the part assigned them in the day’s bloody work,” noted Lt. Joseph J. Scroggs of the 5th USCT. “The [Division Sharp Shooters] were thrown forward as the advance skirmishers and before we had got a mile from camp they had found and engaged the enemy.”

Birney’s battle plan called for his white regiments to deploy across the northeastern face of the Deep Bottom pocket. Their duty was to engage the enemy’s attention, but not to attack. That honor would be given to the black troops on the Union left.

The relatively inexperienced Charles A. Paine was given tactical control of the assault. Though he had seen service from the very beginning of the war, and had risen steadily in the ranks from captain to major to colonel and now to brigadier, the officer had yet to direct more than a brigade in action. Never had he been entrusted with so much responsibility.

Sadly for the men under his command, he was not up to the job. Paine allowed the two regiments of Duncan’s brigade to deploy in what he later termed a “long skirmish line.” He advanced them into the teeth of the enemy’s defenses without any immediate support and before the cooperating white units on their right could get into position.

In the years after the war, Colonel Duncan talked proudly of how his troops performed this day. He vividly recalled the sight of them “in the early gray of the morning, march with steady cadence down into the low grounds in front of Newmarket Heights, when the mists of the morning still hung heavy; saw them disappear, as they entered the fog that enwrapped them like a mantle of death….”

A combination of rough terrain and military obstructions made the Rebel position a formidable one. After crossing an open field, the attackers entered a small wood, running into a deceptively steep ravine and creek. Stumbling out of this clutter, the advancing troops then slogged through some swampy ground before hitting the first line of enemy entanglements—an abatis of slashing, consisting of a belt of chopped-down trees with sharpened branches left on and interlaced.

A small open space separated the slashing from the next entangling strip, a row of chevaux-de-frise—logs bored with slanting holes into which sharpened wooden stakes were placed in a crisscross pattern.

Behind all this lay the enemy earthworks. When the two regiments began their ill-fated advance, the Rebel defenses were dangerously thin, the men spread along their portion of the front at six-foot intervals. But once it became clear that the only threat was coming from two black regiments, Southerners began to crowd in from the flanking trenches.

“There were not many men in the reb. line,” General Paine reported to his father on October 3, “but where I assaulted there were as many men as the works w’d hold.”

The 4th and 6th USCT deployed in two lines of battle, the 4th leading with the 6th echeloned to the left rear. “Our line is formed just back of a crest or knoll over which we are to charge down upon this unknown work,” remembered Lt. J. H. Goulding of the 6th USCT. “As we clear the top, the ground on either side of us seems broken and woody, while that in our immediate front is smooth and slopes down toward the enemy’s line.”

“We could see the first rays of sunlight glinting among the treetops beyond the field,” Captain McMurray of the 6th later recalled, “and noticed a score of Johnnies scampering across the field before us, turning occasionally to shoot back at us.”

The time was about 5:30 in the morning. The black troops had been ordered to load their rifles but not cap them. This was to discourage them from stopping to fire during the rush to the Rebel line. The two lines pressed across the field, tumbled through the ravine and up onto the other side, where the broken lines were reformed. Then the double ranks of blue lurched ahead to the slashing. A few individuals found slight breaks used by the Rebel pickets for passage, while most began to pull at the obstructions, or waited for men with axes to chop a way through. “I know there was a big lot of thinking done by us while we stood there,” remembered McMurray.

With the Federals neatly bunched up at almost point-blank range, the Confederates opened fire. “The crash of small arms is terrific,” wrote Lieutenant Goulding, “a constant roll with the heavier discharges of artillery breaking in like the bass notes of some mighty organ.”

Though they suffered terrible casualties as they clawed through the slashing, the black soldiers struggled ahead. “It was slow work,” said McMurray, “and every step in our advance exposed us to the murderous fire of the enemy. We had little chance for firing, and might almost as well have been without muskets.”

“With shouts and cries, with deep drawn breath and gasps and choking heart-throbs we plunge on and on, men dropping suddenly or thrown whirling or doubled up as they were struck,” Goulding testified.

As he picked his way through the slashing, McMurray found the sickly private, Patterson. He was horribly wounded. McMurray never forgot the sight. “He was shot in the abdomen, so that his bowels all gushed out, forming a mass larger than my hat, seemingly, which he was holding with his clasped hands to keep them from falling at his feet.” McMurray knew the man was doomed to an agonizing death; to the end of his days, he never forgave himself for not letting Patterson sit out that attack.

Small groups of men (the 4th and 6th were by now jumbled together) broke out of the slashing and raced toward the frise. A few who climbed through these obstacles were then mired in swampy ground in full view of the enemy lines. Nevertheless, a handful did reach the Rebel position, only to be killed or taken prisoner.

“The whole line seemed to wilt down under the fearful fire which was then poured into us,” wrote Lt. James Henry Wickes of the 4th USCT to his father on October 4. “The line was growing too weak and thin to make an assault. It began to waver and fall back….”

Two white USCT officers received the Medal of Honor for their conduct in this phase of the action at New Market Heights. Lt. William Appleton of the 4th USCT was acknowledged as the first man of the Eighteenth Corps to enter the enemy’s works, while Lt. Nathan H. Edgerton of the 6th, although wounded, took the flag after three color-bearers had been shot.

Two black noncommissioned officers of the 6th won top honors in this fight. Sgt. Maj. Thomas Hawkins kept the regimental flag from being captured, while Sgt. Alexander Kelly, who also gallantly rallied his men under fire, saved the remaining color of the 6th. Three other black members of the 4th USCT received the Medal of Honor this day: Sergeant Major Fleetwood, Sgt. Alfred B. Hilton, and Pvt. Charles Veal (later corporal).

In the amazingly laconic diary entry he made following his actions that day, Fleetwood wrote: “Saved the Colors.” When interviewed well after the fact, he had a bit more to say. “When the charge was started our color-guard was complete,” he said. “Only one of the twelve came off that field on his feet….Early in the rush one of the sergeants went down, a bullet cutting his flag-staff in two and passing through his body. The other sergeant, Alfred B. Hilton…caught up the other flag and pressed forward with them both. It was a deadly hailstorm of bullets, sweeping men down as hailstones sweep the leaves from the trees and it was not long before he also went down, shot through the leg. As he fell he held up the flags and shouted: ‘Boys, save the colors!’

“Before they could touch the ground, Corporal Charles Veal… had seized the blue flag, and I the American flag….It was very evident that there was too much work cut out for our [two] regiments….We struggled through the two lines of abatis, a few getting through the palisades, but it was sheer madness and those of us who were able withdrew as best we could.”

Colonel Duncan, commanding the brigade, was down with four wounds. Col. John Ames of the 6th took command, his face bloody from a gash across his forehead. “And the going back was worse than the coming up,” noted Captain McMurray of the 6th, “because, to be shot at with your back to the enemy is always more annoying. You feel then utterly helpless.”

“Reaching the line of our reserves and no commissioned officer being in sight,” recalled Sergeant Fleetwood, “I rallied the survivors around the flag, rounding up at first eighty-five men and three noncommissioned officers.”

General Paine later recorded that “Col. Duncan’s brigade…behaved with great gallantry and met with very severe loss….” There were 27 killed, 136 wounded, and 14 missing in the 4th USCT; 41 dead, 160 injured, and 8 unaccounted for in the 6th. In the wake of this failed attack, jubilant Southerners came out of their trenches to plunder the bodies and, by their own admission, finish off some of the badly wounded blacks. Paine’s first attack had been a tragic case of too few men attacking a strong position with no help.

Hardly any time passed before General Birney ordered another assault. Once more the black troops got the assignment. With Duncan’s brigade disordered, Draper now had the call. Unlike Duncan, who spread his troops out in a long line, Draper placed his in a column with the 5th USCT leading, followed by the 36th and 38th—six companies wide, ten ranks deep. “Shells from the rebel battery were poured in upon us,” recalled Colonel Shurtleff of the 5th USCT, “but the fire of the [Union] infantry was withheld. As soon as the whole brigade was uncovered the order was given to ‘double quick’ and we started on a slow run, with arms at a right shoulder shift, the burnished steel bayonets gleaming in the bright sun.”

According to Lieutenant Scroggs of that regiment, “a thick jungle in our way deranged our ranks slightly…but they pressed forward bravely following their colors.”

They, too, were stalled by the abatis. Lt. Elliott F. Grabill of the 5th wrote home on September 30, recounting how the men had to “work our way through bushes and trees cut down to prevent approach with hostile intent.” All the officers who had been riding were now off their mounts. “The shells were shrieking around so that I was afraid one should tear me to pieces while on horseback,” Grabill admitted.

“Within twenty or thirty yards of the rebel line we found a swamp which broke the charge as the men had to wade the run or stream and reform on the bank,” Colonel Draper reported. “At this juncture, too, the men generally commenced firing, which made so much confusion that it was impossible to make the orders understood.”

“Here our progress was arrested and the most murderous fire that I witnessed during the war, opened on us,” Shurtleff remembered. “Our men were falling by the scores,” Draper added.

Incredibly, the Rebel musketry began to slacken after thirty long minutes of this pounding. The cause was neither lack of will nor shortage of ammunition, but rather a startling Union success several miles to the west, closer to Richmond. Butler’s left wing had successfully crossed to the north side of the James, swept aside the Confederates trying to block the road there, and captured Fort Harrison, the centerpiece of the Southern exterior line.

The Rebels quickly realized the greatest danger to Richmond was at that contested point. If Butler’s Yankees could widen the Fort Harrison breach and pour more men into the fight, the defensive shield protecting the capital would be fatally compromised. So, unit by unit, the Confederates holding New Market Heights were hustled out of the trenches and moved off to the west, leaving only a screening force to oppose the USCT regiments.

Butler’s elaborate plan had not considered such an eventuality. The black troops could have demonstrated against the New Market Heights line with skirmishers and produced the same result, while a commensurate increase of the forces allotted to the left wing would have virtually guaranteed a breakthrough that in turn would have dramatically altered the entire shape of Grant’s campaign. Such a strategic appreciation, however, was beyond Butler’s military thinking.

Colonel Shurtleff, caught in the middle of the stalled mass of USCT soldiers who were firing at the enemy, had by now been hit once in the hand. When he checked in with a brigade staff officer, he was told that the original orders to attack were still in effect, and mustering all his strength, shouted, “Forward double quick!” The tangle of men began to advance. Shurtleff hardly had the satisfaction of seeing his orders take hold when he was hit in the thigh. His fight was over.

“The entire brigade took up the shout and went over the rebel works,” Colonel Draper later recalled with pride. “When the brigade were making their final charge, a rebel officer leaped upon the parapet, waved his sword, and shouted, ‘Hurrah, my brave men.’ Private James Gardiner, Company I, 36th U.S. Colored Troops, rushed in advance of the brigade, shot him, and then ran the bayonet through his body to the muzzle.” Private Gardiner was among the nine members of Draper’s brigade who were given the Medal of Honor for their efforts in this action.

Cpl. Miles James of Company B was the other 36th USCT soldier to receive the Medal of Honor in that charge. Though his arm was mutilated by enemy shot, James loaded and fired his gun with one hand while urging his comrades forward. From the ranks of the 38th USCT, Pvt. William H. Barnes was similarly commended for being one of the first to enter the enemy’s works, Sgt. Edward Ratcliff for taking over his company after the white officer in charge had been killed, and Sgt. James A. Harris for gallantry in the assault.

Four Medals of Honor were given to men in the ranks of the 5th USCT: Sgts. Powhatan Beaty, James H. Bronson, Milton M. Holland, and Robert Pinn. Each had taken charge of his respective company when his white officers were killed or wounded. Asked after the war why he decided to join the army, Sergeant Pinn said, “I was very eager to become a soldier, in order to prove by my feeble efforts the black man’s rights to untrammeled manhood.” Pinn’s right arm was badly injured in the fighting that day, and he never regained its use.

“The rebels retreated rapidly and we secured but few prisoners,” wrote Lieutenant Scroggs. “We carried the works but it cost us dearly,” declared Lieutenant Grabill.

Of the 1,300 men of Draper’s brigade who went into the attack, more than 450 were casualties. In the 5th USCT, 28 were killed, 185 wounded, and 23 missing; the 36th lost 21 dead and 87 wounded; and the 38th recorded 17 dead and 94 wounded. Due to the losses in the 5th USCT, command of several of its companies passed into the hands of their black sergeants who, one of them recalled with pride, “discharged their duties to the entire satisfaction of their superiors.”

General Butler, after watching the entire operation, was one of the first to come onto the field after the fighting ceased. “As I rode across the brook and up towards the fort along this line of charge, some eighty feet wide and three or four hundred yards long, there lay in my path [the]…dead and wounded of my colored comrades. When I reached the scene of their exploit their ranks broke, but it was to gather around their general…. I felt in my heart that the capacity of the negro race for soldiers had then and there been fully settled forever.”

Although Butler fixed his attention on what his black troops achieved on this secondary front, the critical actions of the day were with his left wing. Here the Federals had scored an unexpected opening gambit when they found the crossing point undefended. This allowed Major General Ord, the wing commander, to push a strong column north along the Varina Road to within sight of the formidable earthen walls marking the Rebels’ Fort Harrison. At this point in the war, a rush against earthworks usually ended in a bloody repulse, but this time stalwart Federal leadership and poor Confederate morale resulted in just the opposite. The Yanks captured the enemy fort.

A first step had been taken on the road to Richmond, but following up that success proved much harder. The officers lost vital time reorganizing the troops and determining new objectives. While this was happening, enemy fire hit two important Union leaders, seriously wounding General Ord and killing Brig. Gen. Hiram Burnham. With Butler at New Market Heights, there was no one on hand to maintain the momentum of the initial success.

Given priceless time to regroup, the hard-pressed Rebel leaders rallied troops (including those from New Market Heights) to the threatened points. They did not have sufficient numbers to mount a serious counterattack, but they positioned enough soldiers to keep the Federals from easily exploiting their gain. Butler’s decision to remain with his black troops may well have cost him a great victory and, just possibly, a seat in the Oval Office.

While most of Birney’s units quickly formed up below New Market Heights to follow the retreating Confederates toward Richmond, some of the officers and men from the battered black regiments searched the battlefield for survivors. Lieutenant Goulding of the 6th USCT found the color sergeant of the 4th “with both legs shattered by a round shot.”

“Have we taken the works?” the wounded man asked.

“Yes, sergeant, we have,” Goulding replied. The badly wounded soldier began to cheer and gesticulate so wildly that Goulding feared the man would die right there. At last the sergeant allowed himself to be moved out of the sun to a shady area. When told that it was doubtful he would survive his wounds, the sergeant answered, “Well, I carried my colors up to the works, and I did my duty, didn’t I?”

Taking the heights did not end the battle for the black soldiers this day. With Union efforts to the east stalled, the right wing was called on for reinforcements. These troops arrived well after the golden opportunity of the early morning had passed. Nonetheless, several units including portions of William Birney’s USCT brigade were committed to direct assaults against a line of works protecting aroused and determined Southerners. Three regiments of black soldiers were needlessly sacrificed in a futile effort to capture Fort Gilmer, a Rebel strongpoint, adding some 440 men to the casualty tolls.

These failed assaults ended the significant fighting for September 29. Gen. Robert E. Lee counterattacked the next day, but his efforts were repulsed, with the black troops playing a small role in the action. The Army of the James was now firmly ensconced behind fortified lines on Richmond’s doorstep, a position it would occupy until April 3, 1865.

Not long after the actions at New Market Heights and Fort Gilmer, General Butler had a special medal created for about two hundred of the black troops who took part. He described it in his massive postwar autobiography:

The obverse of the medal shows a bastion fort charged upon by negro soldiers and bears the inscription, “Ferro iis libertas perveniet” [“Freedom will be theirs by the sword”]. The reverse bears the words, “Campaign before Richmond,” encircling the words, “Distinguished for Courage,” while there was plainly engraved upon the rim, before its presentation, the name of the soldier, his company and his regiment. The medal was suspended by a ribbon of red, white, and blue, attached to the clothing by a strong pin, having in front an oak-leaf with the inscription in plain letters, “Army of the James.”

“Since the war,” Butler added in 1892, “I have been fully rewarded by seeing the beaming eye of many a colored comrade as he drew his medal from the innermost recesses of its concealment to show me.” Efforts in the twentieth century to have the Pentagon officially recognize the Butler Medal were rejected. According to a 1981 White House letter, “The Department [of Defense] takes the position that a large number of unofficial medals were privately issued to members of the Armed Forces of the United States between 1861 and 1865. The Butler Medal was but one of many in this category.”

Even though the victory won at New Market Heights was needless, it transformed the reputation of the black troops, thereafter acknowledged as dependable combat soldiers within the army. The black soldiers could never forget their unique status in American society of the time, or the larger role they were playing in the war.

While marching toward Richmond right after New Market Heights, some of these black units met a small procession of women and old men escaping from slavery. When the elder patriarch leading the group recognized that his saviors were black soldiers, his exaltation, and that of the USCT men (many of them former slaves), knew no bounds. “They cheered,” wrote a reporter on the scene. “They gathered about the freedman, and…fairly danced for joy, or cried with delight. Men may have their peculiar views about…the policy of arming blacks,” he continued, “but he who could stand by and see those soldiers…and yet could not share in their joy, and thank God with them that other chains were broken, would have been less than human.”

Originally published in the Autumn 2008 issue of Military History Quarterly. To subscribe, click here.