In 1935, the dreaded Nazi SS organization launched a top-secret project that took undercover agents to 260 locations across Germany. Disguised as students and carrying counterfeit reference papers, the agents operated under false names and worked from untraceable safe houses.

What were they up to? Perhaps gathering intelligence to prepare for Germany’s impending war?

No. The agents were sneaking into libraries to research witches.

Hitler Cries ‘Nonsense!’

The Nazi witch project was the brainchild of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, one of the chief architects of the Holocaust and otherwise known for being a delusional fantasist. After rising to power alongside Adolf Hitler as the leader of the Schutzstaffel, better known as the SS, Himmler arranged marriages in addition to mass murder, and spent his spare time trying to find the lost city of Atlantis and the Holy Grail.

He oversaw Nazi interior decorating projects, dug up coffins of famous people, and arranged a publicly funded research project into the meaning of deer symbols — based on a deer-shaped cookie embosser he received as a gift.

There is some dispute as to when exactly Himmler became a complete nutcase. Raised by a strict Catholic family, he was clearly influenced by his schoolteacher father Gebhard, a hardline monarchist. The authoritarian Gebhard stressed the value of “manly” pursuits such as sword dueling — which he actually failed to do himself because of his poor eyesight. Young Heinrich, named after a Bavarian prince, was a sickly and feeble child who did not quite match his father’s ideals. He started keeping a diary at age 10, in which he professed interests not only in dueling but in discussions about religion and sex. Thanks to his father pulling strings with Bavarian royals, the bespectacled lad was accepted into the military during World War I, but the war ended before Heinrich could fulfill his fantasies of frontline glory.

Heinrich Himmler drifted into chicken farming in Bavaria. He found plenty of time to indulge his interests in racism and spirituality — his bizarre contemplations during this agrarian period led him to decide to abolish Christianity and found his own religion.

Other members of the Nazi ruling elite were aware that Himmler was a weirdo in a class by himself, finding his interests “rather quirky.” Hermann Goering regularly made gibes at Himmler for his esoteric forays, and Hitler himself, although opposed to Christianity, was allegedly not terribly thrilled by the idea of Himmler’s style of “new religion.”

“What nonsense! Here we have at last reached an age that has left all the mysticism behind it, and now he wants to start that all over again,” Hitler ranted in exasperation, according to a postwar memoir by his architect, Albert Speer. “We might just as well have stayed with the church. At least it had tradition.”

Why Witches?

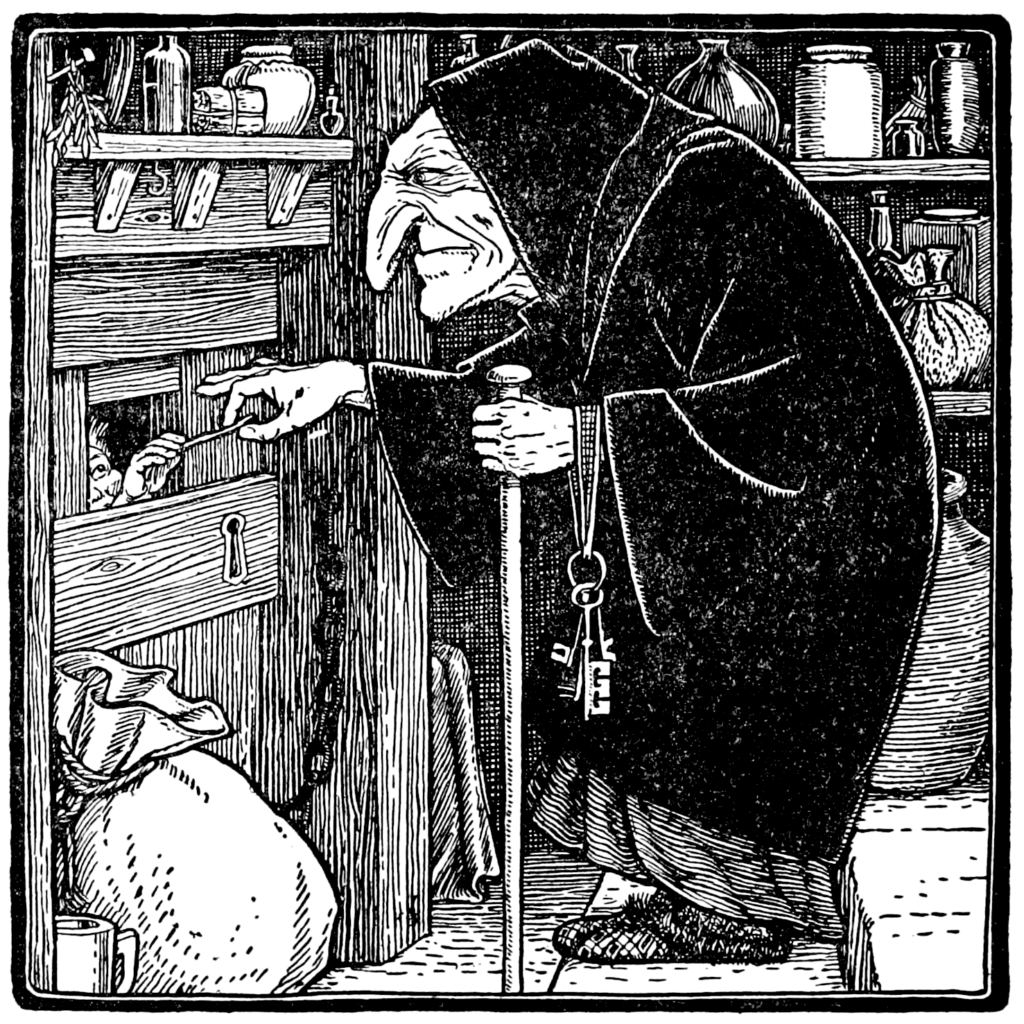

Himmler’s fascination with witches was directly tied into his desire to create his own brand of Nazi-style religion. He wanted to stage spectacles involving torches, solstices, shadows, bonfires and drums. Of course, witches tied into his fantasy — they had after all been popularized across Germany in fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. But Himmler was convinced that there was actually something more behind that evil witch in the tale of Hansel and Gretel than anyone else had realized.

He came to the conclusion that witches were, in fact, Germanic seeresses possessing spiritual powers who were persecuted by a cabal of Catholic priests during the Middle Ages. In keeping with his rabid antisemitism, he alleged that the Catholics were actually the agents of an international conspiracy of Jews. He took his wild theories a step further by claiming that “millions” of witches were actually victims of an anti-German genocide.

“We see how the funeral pyres blazed, on which the battered and torn bodies of our mothers and girls, of our people, burned to ashes in the witch trials!” Himmler railed in a speech to a Nazi farming organization in 1935.

There were, of course, glaring inaccuracies in Himmler’s claims. For one thing, most alleged witches killed in Germany during the Middle Ages were actually the victims of fellow German villagers accusing them of supernatural misbehavior but really just settling scores. According to writer Joachim Wehnelt, German scholars have been able to conclusively prove that “residents of villages often just took out their personal conflicts with someone among them by citing suspicions that the person was a witch.”

For another, it wasn’t only women who were targeted in witch trials, although they did form the majority — men were also accused of being witches, and even 50 Catholic priests were executed for allegations of witchcraft in Würzburg, according to scholar Günter Dippold.

The Jewish community had nothing to do with the so-called “Hexenwahn” (“witch mania”) that swept across various German kingdoms and provinces. And, Catholics aside, Protestants also developed witch paranoia, with Martin Luther notably advocating for the extermination of “sorceresses.”

Lastly, the total number of witches killed amounted to somewhere between 50,000 to 60,000 people, which did not correspond to Himmler’s allegations of “millions.”

But Himmler was not concerned with historical facts. He was only seeking to distort historical events to shape his narrative for his self-concocted SS religion.

“He didn’t care at all about the women as victims,” Armin Fuhrer wrote in Focus magazine. “He wanted to use the crimes against women in the past to justify his own crimes against Jews in the present.”

All In The family?

Himmler also had a personal reason for wanting to warp the history of witch trials. Aside from believing that he was the reincarnation of King Heinrich I, an ancient ruler probably best known for his cameo appearance in Richard Wagner’s “Lohengrin,” he also believed that he was descended from a witch.

Himmler and his cousin Wilhelm August Patin believed that their shared female ancestor had been burned to death at the stake for sorcery. The family claimed that this mysterious ancestor had the mysterious-sounding name of “Passaquay” — which is actually a French surname. Patin, who became an SS-Untersturmführer through his family ties, went around proudly spreading the tales. Himmler ordered his underlings do witch research, maybe to bolster the family myth.

Researchers, however, unsurprisingly found no burnt “Passaquays” were forthcoming.

However, Himmler’s lackey Reinhard Heydrich became involved with the secret witch project and eventually tried to remedy his boss’s alleged lack of witch pedigree in 1939. To provide Himmler with a tangible magical notch on his family tree, Heydrich dug up a certain Margarethe Himbler, executed for alleged witchcraft on April 4, 1629, in Mergentheim, then the headquarters of the Teutonic Order of knights. The gist of Heydrich’s idea was that “Himbler” sounded like “Himmler,” and therefore his boss and the supposed sorceress must be related. However, no link between the alleged witch and Himmler has been proven.

March TO the Libraries!

In 1935, Himmler formed a task force dedicated to researching the existence of witches in Germany. It was top secret and labored in the halls of power, under the very auspices of the Reich Security Service, or S.D., and, from 1939 onwardas part of the Reich Security Main Office, or RSHA. The 14 full-time employees were supposed to make regular reports to the Reichsführer himself.

This ultra-classified project was meant to focus entirely on the study of witches in Germany — their existence, trials, family members, everything. And it was named, not so very secretly, “Sonderauftrag H,” or “Special Mission H,” with the “H” standing for “Hexen,” the German word for witches. In English, this would roughly be the equivalent of labeling witch-related materials with a giant “W” and hoping nobody would notice that “W” stood for “witch.”

The researchers went to elaborate lengths to disguise themselves as students as they sought to gather anything and everything witch-related from libraries and institutions in all corners of Germany. Of course, they were supposed to focus on witches in Germany — but somehow they wandered off-course into other nations such as India and Mexico.

Witch Dances

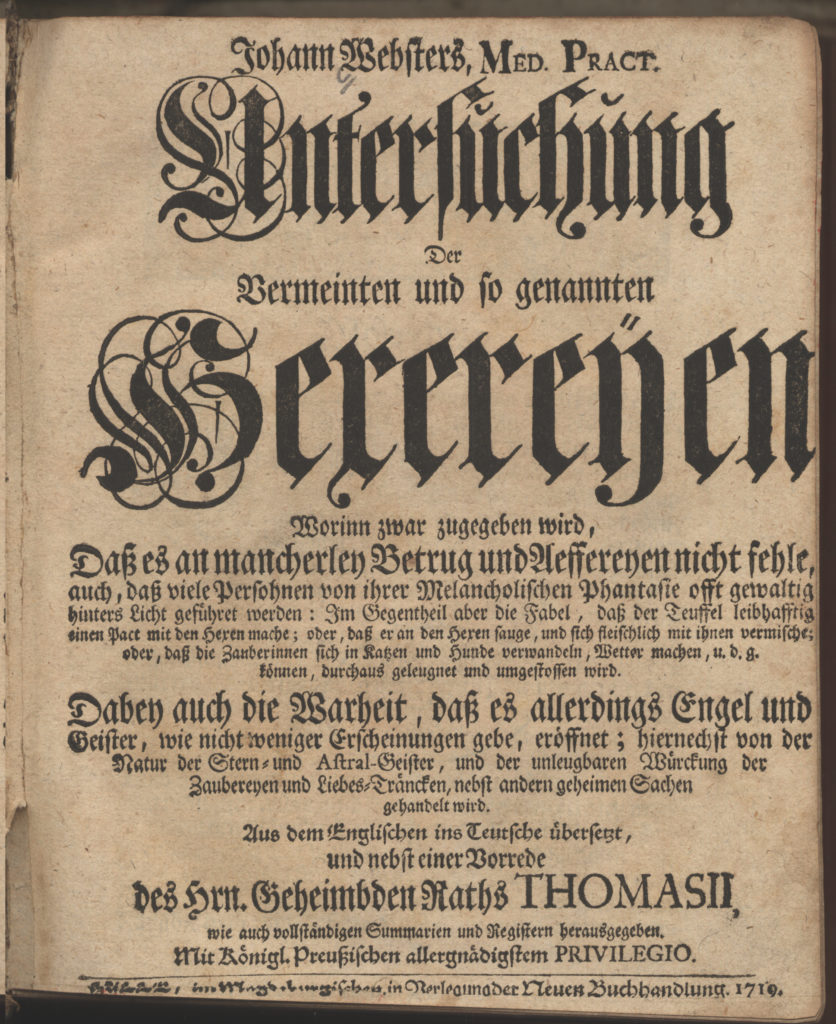

The team rigorously gathered around 140,000 books and written materials related to witches. These included not only books about witch trials but also fiction and fairy tales, as well as the names, addresses, relatives, trial records and execution details of any accused historical witch they could locate. They also created files on sites associated with witchcraft. By 1944, the researchers had indexed 33,846 records.

Their record-keeping was unreliable, however, because the SS task force members were ideologically motivated and demonstrated bias in what they noted and which materials they decided to keep. For example, a librarian from the University of Posen, examining the records later on, noticed that the SS had assembled a dossier devoted to torture methods, underlining phrases about various techniques supposed witches had endured. Based on his findings, the librarian suspected that the SS really wanted to learn how to put these methods to use themselves.

It’s in the Genes

At the root of the Nazi witch project was the belief — or wishful thinking — that medieval witches had truly possessed supernatural powers and had somehow passed them down through the gene pool. For example, SS-Untersturmführer Günther Franz, a professor from the University of Straßburg who worked on the witches project, told SS researchers not to lose heart at the idea of witches being killed off, saying they had “already fulfilled” their marriages — i.e. they must have already passed their presumed witch genes on to their descendants.

Meanwhile, Himmler incorporated “witch dances” into official SS ceremonies. We will never know whether Himmler or other SS members ever attempted to fly on broomsticks or admired chin moles in the mirror, but it wouldn’t be a surprise.

Nazi Witches: The Epic Trilogy

As the young men of Germany fought and died on the front lines of World War II, Himmler and his cronies busied themselves with musing about witches. During the war years, the witch research unit presented ideas to Himmler for further studies, such as “The Economic Repercussions of the H [Witch] Trials.”

The Nazis also developed a plan to broadcast their findings to the public. Ever concerned with propaganda, they decided that ordinary Germans needed an attitude adjustment in terms of witches. Those Brothers Grimm had created problems with their depictions of evil witches, they thought — old folk stories like Hansel and Gretel, despite being German favorites, just wouldn’t pass muster anymore. Witches needed to be cast as “good guys” instead, according to Himmler’s team. They started working on ideas for books and movies.

On the literary side of things, Himmler hired a novelist who went by the name of Friedrich Norfolk (real name: Friedrich Soukup) to pen odes to German witches. The author was delighted at the opportunity. He envisioned a “witch trilogy,” a grand cycle of three massive books, a virtual witch epic, which he proudly proposed to the Reichsführer.

Himmler wasn’t thrilled, though. He had an epic imagination himself but didn’t believe members of the public would chew through three dense books. The most important thing to Himmler was to drill the alleged virtues of witches into people’s brains. Thus, Himmler turned Norfolk’s trilogy down and commissioned “a large quantity of smaller ‘H’ [witch] stories from 60 to 100 pages, which can be read comfortably in the shortest amount of time.”

The Nazis probably imagined Germans on trains and at cafes setting aside their newspapers and doing some light reading about boiling cauldrons along with their morning coffee.

Secret Files or Baffling Malarkey?

In 1945, soldiers of the Red Army swept across Lower Silesia in what’s modern-day Poland. As Russian tanks overwhelmed German towns, Joseph Stalin’s troops seized the town of Slawa, which the Nazis had renamed Schliesersee. Troops entered the town castle. The Nazis had used it as a base of operations; in fact, it had been a bastion of the hated SS.

Men of the Red Army thought they made a hugely important discovery when they stumbled an RSHA archive hidden in the castle. There were thousands of index cards, piles of papers, and a virtual hoard of books.

Assuming they had struck gold in terms of military intelligence, they rushed translators over to unlock the secrets of the archive. To their utter confusion, the soldiers discovered that the data trove was all about medieval witches. It was probably not the watershed moment that Stalin’s commanders hoped for.

Tip of the Iceberg …

The Nazi witch collection is still available for researchers today, although experts consider its historical value limited. According to an article by German journalist Volker Insel, “The scholarly worth of this collection is contradictory for present-day studies of witch hunts. On the one hand, it is an astounding collection of material that includes documents from archives that are no longer accessible or were destroyed. On the other hand, the scientific methods of SS researchers were imprecise and ideologically oriented.”

Many modern-day German scholars have pointed out that the Nazis essentially destroyed their own theories about witches by assembling materials that prove them wrong.

In any case, the witch project was one of Nazi Germany’s most ludicrous special missions. And we haven’t even started telling you about the search for Atlantis yet.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.