PRIVATE FIRST CLASS Dale H. Maple and his two companions completed the first leg of their audacious journey when they crossed the border into Mexico on February 18, 1944. Three days earlier, they had left an army base in Colorado and driven south on a 500-mile trip plagued by flat tires and mechanical breakdowns, but they still had a long way to go.

In Mexico, the trio encountered an inquisitive customs officer. When Maple’s answers didn’t satisfy the officer, he called in American officials, who determined that these were no ordinary travelers. Maple was a U.S. Army deserter, the other two were escaped German prisoners of war, and the three of them were on their way to Germany. The bizarre story of who they were, how they had reached Mexico, and what they ultimately planned to do led to a series of shocking revelations. Most shocking was that Maple was part of a vigorous Nazi insurgency inside the U.S. Army and the key plotter in a grand scheme to fight on behalf of Germany—an act that would come within a hair’s breadth of costing Maple his life.

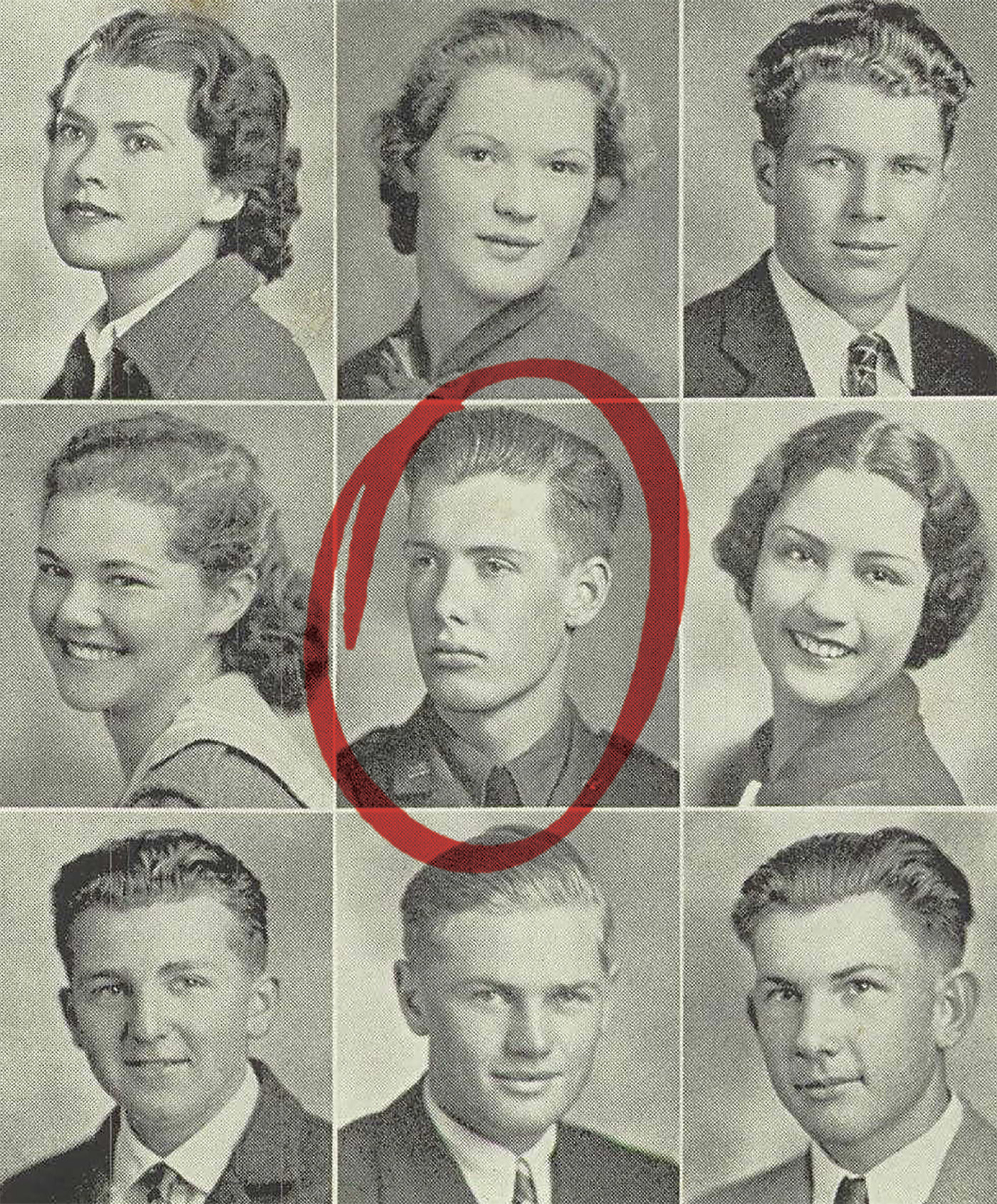

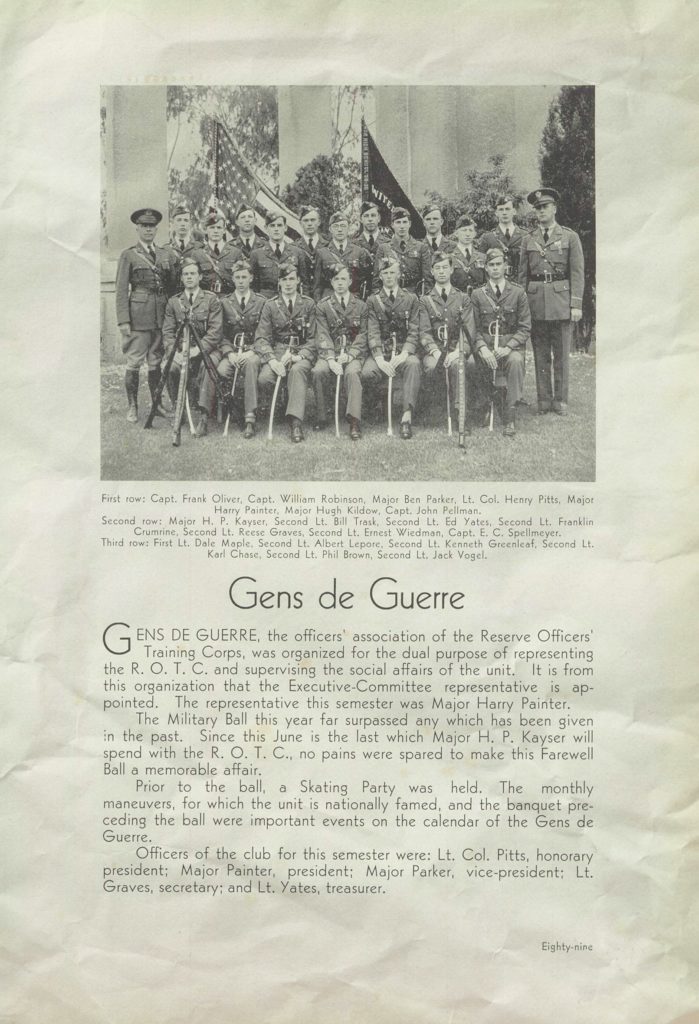

BORN IN SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA, in 1920, Maple had a knack for drawing attention. After his parents bought him a piano when he was 5, he became a musical prodigy, performing works by Beethoven and Chopin at public recitals. With an IQ of 152, he was the top student at San Diego High School, graduating first in a class of 585 in June 1937 and winning a scholarship to Harvard. In college, Maple excelled in foreign languages, easily learning to speak most European languages and majoring in German—his favorite. He showed a keen interest in Germany, a curious fixation as his family was of Irish and English stock. He was also a member of Harvard’s Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC). Standing 5 foot 10 and weighing 160 pounds, he was described as a “quick-witted young man with a ruddy face and ready grin.”

In 1939, at the start of Maple’s junior year at Harvard, war broke out in Europe, and Americans debated how their country should respond. Most wanted to avoid foreign entanglements. A January 1941 Gallup poll showed that 88 percent thought the United States should stay out of the conflict. Their voice was the 800,000-member America First Committee, which advocated neutrality and accused President Franklin D. Roosevelt of trying to drag an unwilling country into war. Critics, however, claimed the group had an anti-Semitic, pro-Nazi tinge. In September 1941, famed aviator Charles A. Lindbergh, America First’s frontman, drew fire for alleging that the American Jewish community was plotting to get the nation into the war.

A more extreme organization was the German American Bund, which unequivocally and unapologetically backed Hitler. The group drew 22,000 supporters to a February 1939 rally at Madison Square Garden in Manhattan to celebrate George Washington’s birthday. “If Washington were alive today, he would be a friend of Hitler,” proclaimed one speaker, the Reverend Sigmund G. von Bosse. A congressional committee chaired by Representative Martin Dies Jr., a Democrat from Texas, found the Bund to be a well-organized group intent on forming a pro-Nazi fifth column in the United States.

Harvard students, too, debated America’s role in the war, joining groups such as the Committee for Militant Aid to Britain and the Committee Against Intervention. Maple never joined any pro-Nazi organizations, but he put himself in Hitler’s corner in other ways. He displayed a plaster bust of the German dictator in his dorm room and attended a costume party dressed as Hitler. He repeatedly contacted the German consulate in Boston, ostensibly for help in pursuing graduate studies in Berlin.

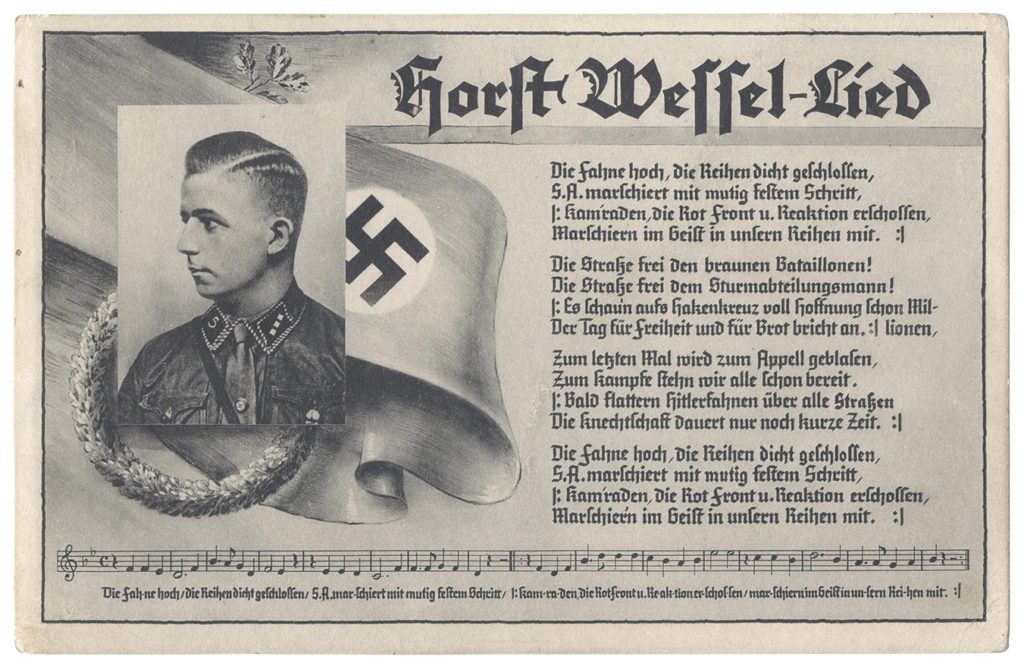

Maple was active in Harvard’s German Club. Members shunned European politics, but Maple repeatedly and stridently injected his Nazi views. The final straw came at a meeting in October 1940 when he persisted in singing the “Horst Wessel Song,” the anthem of the Nazi Party. He was forced to resign from the club, but he didn’t go quietly. He issued a statement to the student newspaper, the Crimson, doubling down on his Nazi views, excusing Hitler’s worst excesses, and claiming that “even a bad dictatorship is better than a good democracy.” This was too much for Harvard’s ROTC commander, who expelled him from the unit. The press took notice, and in its October 28, 1940, issue, Time magazine profiled Maple under the headline, “Making of a Nazi.” The FBI paid attention, too, targeting him as someone to watch if the United States entered the war.

Maple graduated from Harvard magna cum laude in June 1941. That summer, while visiting his father in San Diego, he applied for a job with a defense contractor, the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation. However, he was rejected as a security risk, so he returned to Harvard for graduate school. On December 8, 1941, the day after the Pearl Harbor attack, Maple phoned the German Embassy in Washington. He begged to accompany the diplomatic staff, should it be recalled to Berlin, so he could join the German army, but Maple was politely rebuffed. Hitler declared war on the United States three days later, leaving Maple, as he later explained, “in the position of being in a country at war with a country whose ideals I wished to uphold.”

MAPLE KNEW the security-risk label would haunt him, and he figured that serving in the U.S. Army was the best way to purge the taint. He enlisted on February 27, 1942. Maple was assigned to a field artillery unit at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, then as a radio instructor at Fort Meade, Maryland, and was promoted to corporal before his past caught up with him. In March 1943, the Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) interviewed him, and he was busted to private and shipped to the 620th Engineer General Service Company at Fort Meade, South Dakota.

The 620th was anything but a typical army unit. It consisted of nearly 200 suspected Nazi sympathizers. Some were German nationals, and some had been active in the Bund or America First. Others, like Maple, had made public statements backing Hitler.

At the beginning of the war, the army had realized its ranks included an estimated 1,500 soldiers of dubious loyalty. The Selective Service Act did not bar these men from serving, and none had done anything while in the service to warrant a court-martial. But sending them to ordinary units might create the risk of sabotage and espionage.

On May 19, 1942, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson had ordered these soldiers quarantined in “specially formed organizations” like the 620th and kept under the “strict control” of loyal officers and noncoms. The men in these units would be those “definitely suspected of subversive activity or disloyalty, even though investigation has failed to uncover specific evidence in justification of this suspicion,” Stimson noted. They would be unarmed and given duties “of a harmless character.” As an added precaution, the CIC would set up a network of secret informants to report any suspicious activities by these soldiers. Three such companies were formed in the United States: the 620th; the 358th Quartermaster Service Company at Camp Carson, Colorado; and the 525th Quartermaster Service Company at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.

The men in the 620th quickly figured out that their unit was a make-work outfit composed of soldiers the army didn’t trust. When Maple joined the 620th in South Dakota, he gravitated to an inner circle of Nazi sympathizers that included Theophil J. Leonhard, Paul A. Kissman, and Friedrich W. Siering. Born in Germany, Leonhard, 30, had come to the United States as a child and later taught political science at the University of Texas. When registering as an enemy alien in 1942, as the law required, he had written that he “stood in a condition of allegiance” to the German Reich. Kissman, a 28-year-old refrigeration inspector from Erie, Pennsylvania, had spent several years in Germany and was affiliated with the Bund. Siering, a 27-year-old machinist from Chicago, had been born and educated in Germany. Maple was the only one in the inner circle who was not of German descent and had never set foot in Germany.

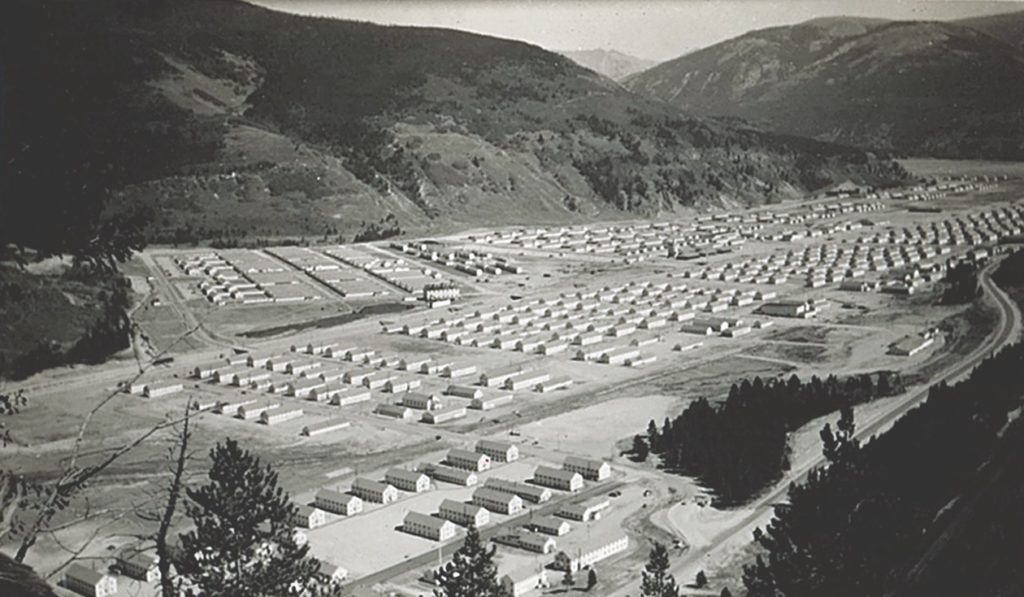

In December 1943, the 620th was transferred to Camp Hale in Colorado. Built in 1942, the camp was home to 16,000 soldiers, including the ski troops of the 10th Mountain Division, a Signal Corps detachment, and a unit of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). It also housed a prisoner of war camp holding 200 members of the Afrika Korps.

Loyal soldiers on the base knew what the 620th was and looked down on these men as traitors, which led to ostracism, insults, and fistfights. The army, too, treated these men as second-class soldiers. It assigned them to the same menial jobs as the prisoners, such as pulling weeds, chopping wood, and shoveling dirt, and issued them the same blue denim work uniforms—the only differences being the 620th’s work uniforms didn’t have “PW” stenciled on the back, and the men of the 620th were as free as other U.S. soldiers to come and go.

Although the army forbade it, the 620th and the prisoners fraternized. The POWs’ stockade was only two blocks from the 620th’s barracks. Many of the Americans spoke German, and they worked on the same details as the prisoners. On December 31, 1943, Leonhard and Siering freed a prisoner they had befriended, dressed him in an American uniform, and took him to Eagle, Colorado, for a three-day New Year’s romp, with Leonhard footing the bill. They returned the prisoner to Camp Hale on January 2, 1944, with the army none the wiser.

EVENTS TOOK A MORE seditious turn a few days later when, on January 8, the inner circle met secretly in a room at Denver’s Shirley-Savoy Hotel with a delegation from the 358th Quartermaster Service Company—the unit of suspected Nazi sympathizers from nearby Camp Carson. The men displayed a swastika, toasted Hitler with champagne, and hatched an extravagant plan. The 358th would stage a mutiny at Camp Carson as a diversion. When troops from Camp Hale rushed to help quell the insurrection, the 620th would seize the Camp Hale armory and free the German prisoners. The 620th and the prisoners would then wage guerrilla warfare in the Rocky Mountains. They hoped, Maple said later, “to disrupt the internal economics and morale of the country to such an extent that further participation in the war would be impossible….”

When this flamboyant plan never got beyond the talking stage, the inner circle worked out a scaled-down version: Maple would desert and take two prisoners with him, traveling to Germany by the circuitous but only available route via Mexico, Argentina, and Spain. In Germany, he would arrange contact between German spies and the 620th with an eye toward sabotage. The inner circle successfully evaded Camp Hale’s CIC informant network because a WAC had leaked details of the surveillance system to her boyfriend in the 620th.

Maple borrowed money from his parents to finance the trip, telling them he needed it to pay a college debt. Theophil Leonhard, who was familiar with Mexico from his years in Texas, advised Maple on Mexican geography, gave him a list of supplies he would need, and tipped him off to a pawn shop in Denver that would sell him weapons. In late January 1944, Maple gave Paul Kissman $50, and Kissman bought equipment for Maple’s trip, including a .38-caliber revolver. On February 12, Maple and Kissman went to Salida, Colorado, for more supplies: a yellow woman’s sweater, scarf, and handbag to disguise one of the escaping prisoners as a woman. The next day, they visited Salida again. This time, Maple bought a car—a tan 1934 REO sedan—for $250, plus $5 sales tax.

Two days later, Maple carried out his plan. On February 15, he slipped away from his work detail at a nearby sawmill, as Kissman covered for him. He drove off the base and met the two escaping German prisoners, Heinrich Kikillus, 33, and Erhard Schwichtenberg, 25. They hopped into the REO, and Maple drove south through Colorado and into New Mexico. They conversed in German, ate their meals in the car, and slept in the vehicle on the nights of February 15 and 16. Rationing had made good tires scarce, and they had to fix several flats along the way. When the REO broke down in New Mexico, they got a push-start from an unsuspecting off-duty U.S. customs agent. Twelve miles from Mexico, the car conked out for good, and they crossed the border on foot.

At 4:30 p.m. on February 18, Maple and the prisoners encountered Medardo Martinez Mejia, a Mexican customs official, near the border town of Palomas, Mexico. Wearing a hat with the brim pulled down to hide his face and feigning a German accent, Maple identified himself as Edward Mueller and offered up background information he’d learned from a POW. He said he and his companions were seeking work in Mexico. Mejia became suspicious when they couldn’t produce passports. He and another customs official became even more suspicious when Maple changed his story and said the trio was bound for Germany. The Mexican authorities called in William F. Bates, a U.S. immigration official, who drove the men back to New Mexico. Maple told Bates he and his companions were Jewish refugees from Europe, but Bates thought they might be German prisoners who had recently escaped from a camp in Amarillo, Texas.

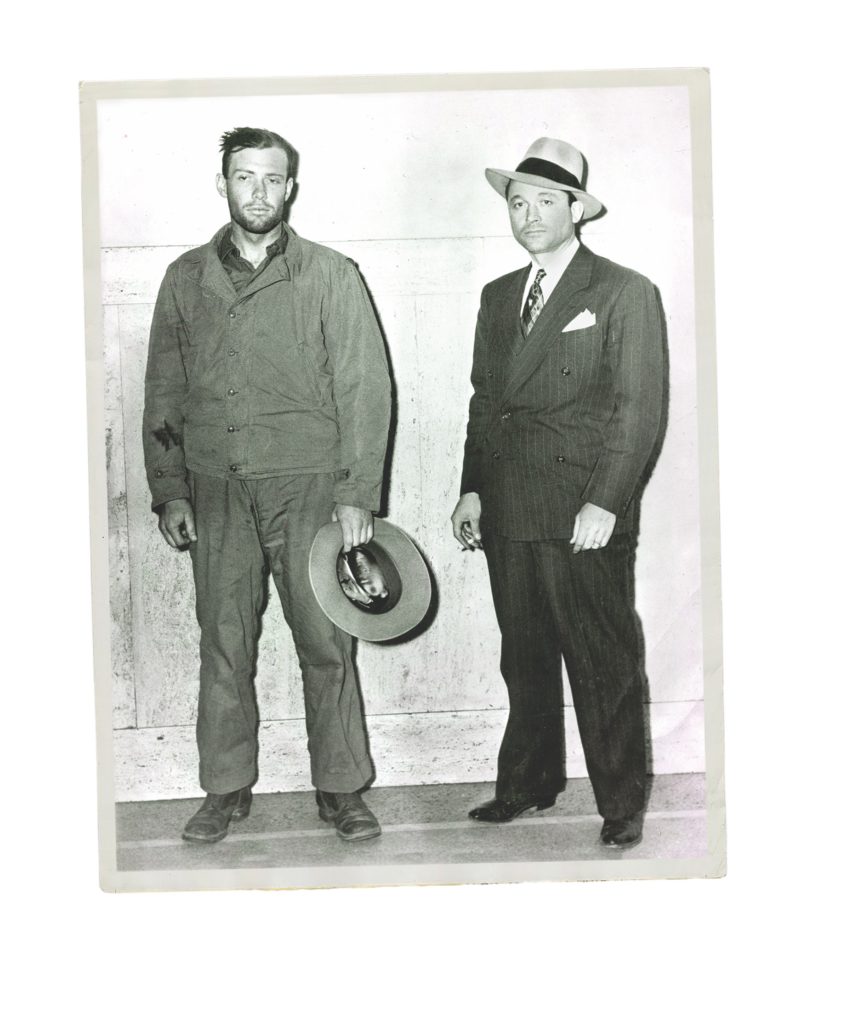

FBI Agent Delf A. “Jelly” Bryce grilled Maple for five hours, and Maple eventually dropped his German accent and revealed his true identity. He confessed his subversive activities and implicated his accomplices. He even volunteered a plan he claimed he had devised to cripple the American rail system, vital for moving troops and military equipment. Bryce was skeptical, but Maple drew a map showing the bridges and junctions whose destruction would immobilize rail traffic. The FBI arrested Maple and charged him in federal court with treason.

A letter found in prisoner Schwichtenberg’s possession confirmed the motive behind the escape. Written by Leonhard in German and given to Schwichtenberg to deliver to Nazi officials, it identified Leonhard as the “leader of the boys, that are ready to stake all for Germany.” If Nazi agents contacted him, “everything will be possible,” Leonhard wrote, later admitting that “everything” included sabotage and espionage. Leonhard’s letter boasted that “when the hour comes I shall without doubt gladly give my life for Germany.”

AFTER MAPLE’S ARREST, the army raided the 620th’s barracks and the prisoner compound, but the 620th had anticipated this and destroyed all incriminating items. The German POWs had done the same—although not as thoroughly. Hidden in a wall, the army found 20 gallons of fermenting fruit from the prisoners’ bootlegging operation and love letters from five WACs, who were later court-martialed for their indiscretion.

The FBI’s criminal charge against Maple presented a problem because a civilian court trial would be public. Any disclosure of Nazi sentiment and subversion in the U.S. Army would embarrass the army and give Germany a propaganda windfall. The case was transferred to a military court, which would meet behind closed doors. The army charged Maple under the Articles of War with the military equivalent of treason (Article 81) and desertion (Article 58), both capital offenses.

On April 17, 1944, Maple’s trial began in the Disciplinary Barracks of Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, before a court consisting of two generals, seven colonels, and three lieutenant colonels. The two German prisoners testified against Maple, as did Leonhard, Kissman, and Siering. Prosecutors presented an airtight case, but Maple thought he could change the narrative.

He took the stand and told an outlandish story, swearing that he had acted as an American patriot to vindicate himself and his outfit. He described the 620th as “two hundred highly capable, honest, loyal men,” with only a few disloyal ones, and said he believed the army had stigmatized the entire company as traitors. By pretending to be a Nazi, he said, “I was accepted with open arms by the more radical elements, and became acquainted with all their plans and schemes.” He hoped, he testified, that “by making this information available at a proper time to the correct authorities, I might prove my loyalty to America.”

His escape, Maple insisted, was part of this plan, orchestrated so he would be caught and tried for treason in federal court. “While I controlled this limelight of publicity, I would turn it from myself to [exonerate] the 620th Engineers,” he said. He knew his actions might be misunderstood, but said he had “so great confidence in the ultimate judgment and justice of the American people that I was willing to take the risk.”

Prosecutors quickly confronted Maple with a letter he had written to Kissman while awaiting trial. In it, Maple outlined his plan to dupe the judges, asking Kissman, Leonhard, and Siering to play along. “Will use abused Americanism angle,” he wrote. “Pass word to others: We’ll lay it on thick.” This letter, an army review board later concluded, “exposed the whole fraud of his defense.”

With Maple’s credibility in tatters, his civilian attorney, Humphrey Biddle, took the only avenue left to him, arguing insanity. “No human being of his background and being in his right mind could have done what he did,” Biddle contended, but the judges weren’t persuaded. On May 8, 1944, they convicted Maple on both charges and sentenced him to be hanged, making him the war’s only American soldier to be sentenced to death for treason.

The army wasn’t squeamish about capital punishment: between 1941 and 1946, it would execute 140 soldiers for rape and murder, and one for desertion. Maple’s fate rested with the authorities who would review his sentence. On June 22, 1944, a four-officer Board of Review affirmed the sentence, but the final decision rested with President Roosevelt.

As the case headed to the White House, Maple acquired an unlikely benefactor: Major General Myron C. Cramer, the army’s judge advocate general. The 63-year-old lawyer was no soft touch. He had prosecuted the eight German saboteurs who had landed on Long Island and in Florida in June 1942. He had argued vigorously for the death penalty, and six of the saboteurs had been swiftly executed in August 1942. After the war, he would serve as a judge on the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which would sentence seven Japanese political and military leaders to death.

Cramer saw Maple’s case as calling for a more benevolent form of justice than Maple’s Nazi heroes would ever have given him. “I feel that the ends of justice will better be served,” Cramer wrote to the president, “by sparing his life so that he may live to see the destruction of tyranny, the triumph of the ideals against which he sought to align himself, and the final victory of the freedom he so grossly abused.” Roosevelt agreed, and on November 18, 1944, he commuted Maple’s sentence to a life prison term and a dishonorable discharge. Maple was sent to the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth to serve his time as prisoner number 61364-L.

Maple was not the only one punished. Leonhard and Kissman were each sentenced to life in prison and a dishonorable discharge for helping Maple plan and carry out his escape. The army couldn’t tie Siering directly to the plan, but he was given a 10-year prison term and a dishonorable discharge for taking the German prisoner out for his New Year’s frolic. Ironically, the escaping prisoners, Schwichtenberg and Kikillus, faced no penal consequences. Under the Geneva Convention, a prisoner could not be prosecuted for escaping.

The army had disbanded the 620th—along with the 525th and 358th—shortly after Maple’s arrest and reorganized the men into a single unit, the 1800th Engineer General Service Battalion. The German Americans of its new Company A were assigned to a camp at Bell Buckle, Tennessee, where they spent their time repairing damage to farms caused by army maneuvers. After the war, the government gave these soldiers a final insult: blue discharges. These discharges, named for the color of the paper on which they were printed, were considered neither honorable nor dishonorable; still, they disqualified these men from benefits like the G.I. Bill.

In 1946, the army reduced the sentences of soldiers incarcerated in federal penitentiaries for court-martial convictions. Maple was released from Leavenworth on October 8, 1950; Leonhard, Kissman, and Siering were freed at about the same time.

Maple quickly put his past behind him. He got a job with the National Steel & Shipbuilding Company in San Diego and developed an expertise in marine insurance. In 1964, he became an insurance manager for the American National General Agencies and retired as a vice president in 1978. In his later years, he dabbled in computers and pursued his hobby of building organs, but he refused to discuss his abortive escape. He died in 2001.

Maple’s attempt to lead the escaped prisoners from Colorado to Germany cost him six years of his life and was a fool’s errand from the start, a grandiose and delusional plot with no chance of success. Of the 435,788 German prisoners held on American soil during the war, 2,222 escaped. Most were recaptured within days, and not a single one succeeded in reaching Germany. Maple wasn’t as clever as he thought he was. ✯

This article was published in the June 2021 issue of World War II.