In 1869, Jules Verne wrote Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, a novel about circumnavigating the globe underwater, in which he introduced readers to Captain Nemo’s submarine, Nautilus. Lauded ever since for predicting the advent of maritime travel under the waves, Verne was actually expanding upon the recent inventions of various men who applied the use of “sub-marines” to both commerce and warfare. The brainchild of one such man—Brutus de Villeroi—became the first submarine adopted for use by the U.S. Navy.

De Villeroi had been successfully experimenting with under-the-ocean salvage vessels in his native France since the early 1830s. Shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War, de Villeroi—who had immigrated to the United States—offered his “Sub-Marine Propeller” to the Union Navy in a most dramatic way. He surfaced in one of his vessels off the Philadelphia Navy Yard—and was immediately arrested by the harbor police on suspicion of sabotage. Northern newspapers jumped on the story. The May 17, 1861, edition of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin ran a breathless account of the event:

Never, since the first flush of the news of the bombardment of Fort Sumter, has there been an excitement in the city equal to that which was caused in the upper wards this morning, by the capture of a mysterious vessel which was said to be an infernal machine, which was to be used for all sorts of treasonable purposes, including the trifling pastime of scuttling and blowing up Government men-of-war.

The article goes on to describe the “infernal machine” in detail, giving the residents their first glimpse of a Civil War–era submarine:

Externally it had the appearance of a section of boiler about twenty feet long, with tapered ends, presenting the shape and appearance of an enormous cigar with a boiler iron wrapper…. The after end was furnished with a propeller, which had a contrivance for protecting it from damage from coming in contact with external objects. The forward end was sharkish in appearance, and the shark idea was carried out in other respects, as only the ridge of the back was above water, while the tail and snout were submerged. Near the forward end was a hatchway or ‘man-hole,’ through which egress and ingress were obtained. This whole was covered with a heavy iron flap, which was made air tight, and which was secured in its place by numerous powerful screws and hooks. Two tiers of glass bull’s eyes along each side of the submarine monster, completed its external features, afforded light to the inside, and gave it a particular wide awake appearance.

While the Saturday Evening Post ran a similarly sensational account, calling the vessel “a monster, half aquatic, half aerial, and wholly incomprehensible,” the New York Times cut right to the possible application of such a craft: “It supplies its own air and will be useful in running under a fleet.”

Once de Villeroi, 67, made it clear that he represented no threat to the locals, government naval representatives inspected his boat and commissioned him to build them a larger version. Although he had initially designed his vessel as a salvage craft, the Union Navy saw in his invention a means to clear enemy harbor entrances, as well as a weapon with which to neutralize the newly minted Southern ironclads—most specifically, the Virginia, more popularly known as Merrimac.

The Navy hired the aged de Villeroi to oversee construction, at an annual salary of $2,000. He proved to be a temperamental genius, and the Navy was a difficult and obstinate partner. There were frequent misunderstandings and acrimonious letters between them before, finally, an embittered de Villeroi was removed from the project. “M. de Villeroi was not handsomely treated by the authorities in Washington,” states his obituary in the July 3, 1874, Philadelphia Inquirer. “He was discharged and others took the glory and fruits of his labors and studies.”

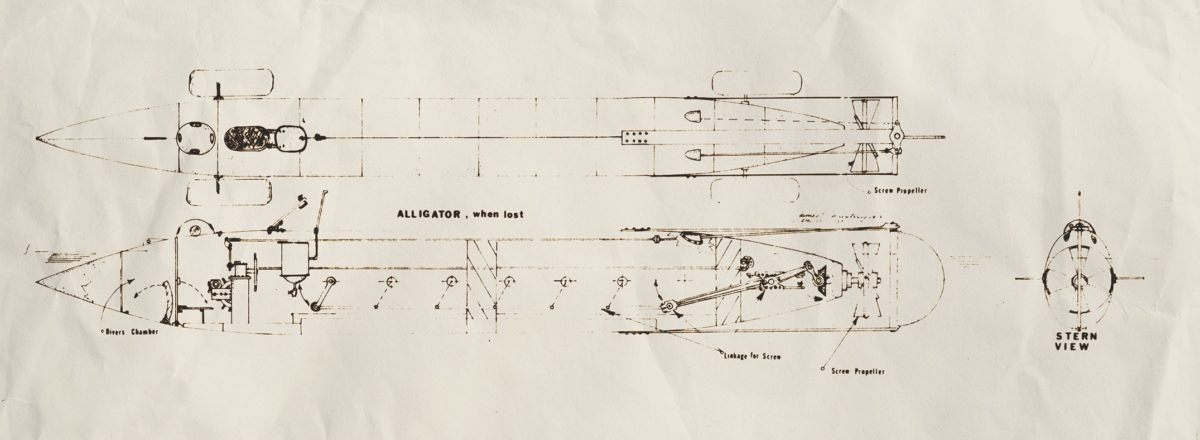

Construction wasn’t completed until late spring 1862—more than four times longer than anticipated—by which time the Virginia was no longer a threat. The finished vessel, running some 47 feet long and painted green, inspired the unofficial name Alligator. Among its brilliant innovations was an air-purifying system that filtered oxygen through lime to remove carbon dioxide—unheard of in any other sub-ocean vessel of its time. But at the Navy’s insistence, it was propelled by that most ancient of methods— oars, manned by a crew of 16.

Alligator first assignment bespeaks the Navy’s ignorance regarding the use of submarines. The ship was to ’s navigate up Virginia’s Hampton Roads and destroy a railroad bridge over Appomattox Creek. There were no torpedoes in use at this time—or, at least, the kind propelled from a vessel at a specific target. The term “torpedo” had a different application during the Civil War, referring to a floating mine or a surreptitiously planted bomb. But one of Alligator’s more futuristic innovations, anticipating the Navy SEALs of our own time, was its ability to deploy through a forward airlock a diver who could swim ashore with explosives.

Alligator did not complete its mission. Fortunately for the ship and its crew, they were warned away because of shallow water, which would have necessitated surfacing—almost certainly resulting in capture. The Navy conducted tests with Alligator over the course of the next several months, replacing its oars with a hand-cranked propeller and increasing its speed to 7 knots. Named as “acting master” was a civilian, Samuel Eakins, who had recently been a professional salvage diver at Sebastopol for the czar of Russia. Eakins added a conning tower for observation to Alligator’s hull, and in early 1863, received orders for a new operation. Charleston, S.C., had been a Rebel stronghold since the Sumter surrender. Determined to capture the port city, Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont, in command of a fleet of ironclads, ordered Alligator to clear the harbor entrance of mines and other obstructions.

Alligator went under tow behind USS Sumpter [sic], a Navy steamship, to make the sea journey to Charleston. Unfortunately, the route went around Cape Hatteras, known even then as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic.” Sumpter’s Acting Master J.F. Winchester later described a “furious gale from SW” that suddenly buffeted both vessels, and Alligator— graceful under the water but helpless in the waves—took an especially terrible pounding. Its ports let in water and its metal plates came loose, letting the ocean in as it wallowed in the rough seas behind Sumpter. Eventually one of two the lines holding Alligator to the mother ship parted, and—for the survival of Sumpter and its crew—the order was given to cut the submarine loose. As Sumpter struggled in the pounding waves—in Winchester’s words, “plunging under to the foremast”—Alligator swiftly went down at its stern.

Somewhere in the depths off Cape Hatteras lies a long, green vessel with a fascinating story. Perhaps in time Alligator will be salvaged from the ocean floor and get the attention it merits.

Historian Ron Soodalter is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader.

Originally published in the November 2011 issue of America’s Civil War.