First federal infrastructure project cut a path to the future

TODAY VEHICULAR TRAFFIC whips effortlessly in both directions across the Appalachian Mountains, which separate the Eastern Seaboard from the American heartland. In early colonial times, however, that low-lying cordillera, though ancient and worn, nonetheless functioned as a near-impassable barrier. With plenty of land still available east of the mountains, only those traveling light and most determined to go west—Native Americans, trappers, traders—traversed the Appalachians.

However, in 1754, Austria’s rulers, the Habsburgs, decided to grab back Silesia, a province in what is now Poland, that Prussia had snatched. The resulting conflict ignited the Seven Years’ War, a European contest that spilled into the world at large. France sided with Austria. Britain sided with the Prussians. Each saw in that continental conflict a chance to evict the other from North America’s Ohio River Valley, which both Britain and France claimed.

France claimed Quebec and all the land drained by the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Britain declared that it owned North America between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The global confrontation’s American portion, the French and Indian War, brought the first road over the Appalachians into being. That artery grew and evolved to become U.S. Route 40, the National Road.

In 1755, intent on ejecting France from the Ohio Valley, the British crown assigned General Edward Braddock to attack Fort Duquesne, a French bastion at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers in what is now southwest Pennsylvania. To take Fort Duquesne, Braddock had to march nearly 2,500 troops from Alexandria, Virginia, across the Appalachians. To cross the mountains with wagons, horses, cannon, and supplies enough to sustain themselves and to prevail by siege, those troops needed to build their own road (see “Road to Nowhere,” below).

Braddock was commanding British regulars who had been garrisoned in Ireland and were the first Redcoats in the American colonies in 70 years. The only colonial on Braddock’s staff was George Washington, who well knew the region Braddock’s regulars would be traversing; in his younger days, the Virginian had surveyed the area. A year earlier, in 1754, Washington, at the time a British officer, had led Virginia militiamen in losing fights in the Appalachians against Frenchmen and Indian allies at Jumonville Glen and Fort Necessity. Those defeats, the first engagements in the French and Indian War, galvanized Washington into resigning his commission and the British into mounting what became Braddock’s expedition. A year later, accepting an informal captaincy Braddock had proffered, Washington joined the newly arrived Redcoats at Alexandria. From that port, augmented by colonial militiamen and fresh recruits, Braddock’s corps on May 29, 1755, began a 300-mile march west. The 145-mile first leg brought the force to Fort Cumberland, near what is now Cumberland, Maryland. Braddock’s men began building a 12-foot-wide military road that would wind northwest around mountains and across rivers and creeks to get the soldiers near enough to Fort Duquesne to lay siege. The British expected an easy victory. The British were wrong.

Building the military road proved punitive. The exhausting two-month exercise ended with Braddock’s force routed and its general grievously wounded during the Battle of the Monongahela. On July 13, as his former command was retreating east on the new road, Braddock died. To spare his corpse desecration by the foe, Washington had Braddock buried in the roadbed, then marched troops and teams pulling wagons over the spot until

hooves, boot heels, and iron wheels had obliterated the general’s grave.

British troops and colonial militia eventually drove the French out of Fort Duquesne, renaming the captured bastion for Prime Minister William Pitt—hence Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Britain’s 1763 victory in the French and Indian War left the crown owning the land east of the Mississippi and north of the Ohio. Upon achieving independence in 1783, the United States of America took possession of 260,000 square miles of that holding.

Into the region, now called the “Northwest Territory,” streamed settlers. One was Ebenezer Zane, who had been a colonel in the Continental Army. During the Revolution, Zane had stood fast in two British sieges near what is now downtown Wheeling, West Virginia. In 1796, he approached Congress with a plan to build a road starting at Wheeling and continuing across the Northwest Territory to the Ohio River near Cincinnati. To fund the venture, Zane requested land grants at river crossings that he could subdivide and sell, as well as a concession to ferry travelers from shore to shore. Congress conferred those grants. With his brother, son-in-law, and native guides, Zane set out.

As a road-building crew, Zane and company were not very formidable, and the road they built—Zane’s Trace—was not very impressive. The construction crew generally followed existing native trails, which the men widened by felling trees where necessary. Occasionally the workers marked the route but did very little to improve trails into roads able to handle traffic heavier than the occasional pedestrian or rider. Zane’s Trace included steep ascents and descents dangerous for horse-drawn wagons, and in places was not even wide enough for two wagons to pass one another.

Zane’s Trace became a relatively straight 230-mile path north of the Ohio River linking Wheeling, West Virginia, to Maysville, Kentucky, across the Ohio. Upon its completion the authorities suspended roadbuilding in the new territory. Seven years later, in 1803, when Ohio was carved out of the Northwest Territory, Zane’s Trace was the only road in that entire state. In 1804, workmen repairing what had become a thoroughfare uncovered Braddock’s bones and medals near what is now Farmington, Pennsylvania.

Lawmakers recognized the need for roads in the Northwest Territory, and in admitting Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois stipulated that federal lands in those states could be sold to fund road construction. In 1806, Congress made

its first use of the provision to sell frontier lands and authorized construction of a National Road—the nation’s first infrastructure project. Five years in the planning, the National Road was to begin by modernizing the 115-mile run of Braddock’s Road from Cumberland, Maryland, into Pennsylvania, then cut a new route from Pittsburgh to Wheeling.

The original road statute called for dispatching three “disinterested citizens” to survey the route from Cumberland to Wheeling. The road, including rights of way, was to be four rods—66 feet—wide, at the time a common road breadth. Road-building materials were up to the builders, but the road had to have drainage ditches on either side and a maximum grade of 8.75 percent. Before work could start, legislatures in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania had to give permission for the road to pass through those states, reflecting the still-gelling notion of federal authority.

Planning was supposed to be done by those “disinterested citizens,” but the route from Pittsburgh to Wheeling was more or less up for sale. Tavernkeepers and merchants in Uniontown and Washington, Pennsylvania, were able to temper the state’s approval with a condition that required the route to pass through those towns. Initially opposed to this horse-trading, President Thomas Jefferson finally accepted the stipulations when Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, the road’s main backer in the cabinet, explained the political cost of trying to override them.

The first bids for the Cumberland to Wheeling stretch of road were let in 1808, with construction starting in 1811. The roadway itself was to be 20 feet wide, paved with 12 to 18 inches of stones, its surface crowned to shed runoff into ditches at either side. In 1818, the road reached Wheeling, where construction stalled.

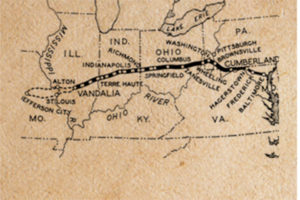

As early as 1808, in a message to Congress, President Jefferson was calling for completion of the National Road as far as St. Louis. From Wheeling the road would follow the path of Zane’s Trace as far as Columbus, Ohio.

From Columbus crews would break new ground in a westerly direction roughly parallel to and about 100 miles north of the Ohio River all the way to the Mississippi.

Progress halted between 1818 and 1824 while Congress, President James Monroe, and the Supreme Court disputed the constitutionality of federally funded projects like the National Road. Gibbons v. Ogden, a landmark case involving steamboat concessions granted by state and federal governments, settled the question in 1824 in favor of congressional authority to build roads and make other improvements. After Ogden, surveying and construction resumed in Ohio in 1825 and began in Indiana in 1827. The route reached Zanesville, Ohio, in 1830, Columbus in 1833, and Springfield by 1838. In Indiana, surveying crews set out from Indianapolis, laying the road arrow straight in both directions. Indiana was less populous and had a terrain more amenable to roadbuilding, enabling crews to work to a lower standard and lay a road across that state by 1834. Surveyors set out from the eastern border of Illinois in 1828, aiming for but never reaching the Mississippi.

Repair and maintenance costs proved troublesome. Congress had provided for sale of public lands to fund road construction, but had not funded upkeep. Lawmakers were loath to spend general funds to maintain a road benefiting only a few states. The solution was to sign over the road to those states and let them fund maintenance by charging tolls. Through the 1830s, federal appropriations bills funded construction, and on completion, the federal government titled that section of road to the state in question. By project’s end, Congress had spent almost $7 million building the 620-mile road.

By 1839, the National Road was largely completed from Cumberland, Maryland, to Vandalia, Illinois, where construction of the original road stopped for good. Save for a few stretches paved with crushed rock and sections of corduroy—logs laid perpendicular to the path—the National Road in Illinois was mostly ruts punctuated by stumps cut low enough for wagons to pass. Residents of western Indiana and Illinois hoped for an upgrade but interest in improving hinterland highways was thin in Washington. During his term, between 1837 and 1841, President Martin Van Buren openly opposed further roadbuilding. Voted out of office, Van Buren was on the hustings in 1842 when he passed between Indianapolis and Terre Haute. Locals decided to demonstrate to the infrastructure-loathing ex-president the National Road’s awful state—by staging an accident. Outside Plainfield, Indiana, Van Buren’s coachman, who was in on the scheme, swerved, ostensibly to avoid an elm tree, dumping the former president into the mud. Lacking wheels and dripping Hoosier muck, Van Buren had to walk to a nearby inn and clean up before continuing to Indianapolis.

In the East, the road proved so resounding a success that as early as the 1820s users were calling for repairs and improvements, just in time to bring to bear a new roadbuilding method. In Scotland, amateur engineer

John McAdam, formerly of New York, was developing the first innovation in paving since Roman times. Macadam pavement, as his product came to be called, layered crushed rock into a surface almost as durable as cemented cobblestone. A McAdam surface consisted of carefully graded and sized rock, with the smallest-diameter stones at the surface. The weight of wagons and carriages rolling on iron-rimmed wheels tightly compressed the layers into a matrix nearly as solid as if stonecutters had hewn and laid larger pieces of pavement. Workers were assigned to use iron rings for gauging rock size, but the easiest test for the top layer’s roughly one-inch diameter pieces was an open yap. If a worker’s mouth could hold the piece, it was right for the road. McAdam’s method is still used on gravel roads, with wire screens replacing mouths. The first stretch of National Road was done before McAdam’s paving method crossed across the Atlantic, but eastern reconstruction from the 1820s on relied on McAdam’s system.

While state and federal governments bickered about expenses, a way of life took form along the road. Taverns, inns, stagecoach waystations, and towns came to dot the interstate artery as merchants, publicans, and other businessmen who had started enterprises at the road’s eastern end followed the pavement toward the sunset, capitalizing on opportunities farther and farther west and establishing a community and a culture centered on the road itself.

From the 1830s to the 1850s the stretch from Cumberland, Maryland, to the Ohio line saw unprecedented traffic and commerce. Teamsters with brightly painted Conestoga wagons that could haul five tons of freight crossed the Alleghenies, making 15 to 20 miles a day. Stables were scarce, but in fall and winter canny teamsters knew to carry blankets. A teamster recalled seeing 30 six-horse teams at one inn, along with 100 mules. In pens surrounding that public house were a thousand head of cattle and pigs, some kept for guests of the inn, others put up for the night by drovers taking them to market. Inside, after a meal that as likely as not featured buckwheat cakes, teamsters spread bedrolls in the dining room, their sleeping forms radiating in a half-circle around a stone fireplace that in winter was roaring and in summer cool to the touch. The National Road more or less spawned the trucking industry, as “long-haul” teamsters carried freight between the Northwest Territory and the Atlantic Seaboard.

During the day so many wagons and stages crowded the road that horses hitched to one wagon would be close enough to the wagon ahead to nibble from its feed trough—not bumper-to-bumper but snout to grain. In 1848, Robert McDowell, who was traveling the National Road, counted on one stretch 133 wagons, each drawn by six or more animals. Smaller teams were so plentiful that they were not worth tallying, McDowell said.

Stagecoach lines were competitive and their drivers more highly strung, driven to hurry between stops at top speed. Way stations maintained spare teams, and hostlers, as service personnel were known, became expert at quickly changing teams. On the road, drivers learned to stay just this side of absolute recklessness—most of the time. A driver for the Good Intent Line in Pennsylvania and Virginia used to taunt rivals, “If you take a seat in Stockton’s line/You are sure to be passed by Pete Burdine.” When one of Stockton’s drivers outpaced Pete, he bellowed, invoking the name of a rival company, “Said Billy Willis to Peter Burdine/You had better wait for the Oyster line.”

In roadside towns, stagecoach drivers, teamsters, tavern keepers and those that worked with them were known as Pike Boys—the artery also was known as the National Pike, as in “turnpike,” after the moveable barrier used to stop traffic to collect tolls on private roads—a nickname that was a point of pride or a slur, depending on who was using it.

From Cumberland to Uniontown and Washington, Pennsylvania; from Wheeling to Zanesville, and Columbus, Ohio, and farther west into Indiana and Illinois, the National Road was the Main Street in towns now small and large, the first road called “America’s Main Street.” The Road’s standing may have peaked in 1849, when ferry service across the Ohio yielded to an engineering marvel, the world’s longest suspension bridge. The bridge’s deck hung on steel cables strung between two towers over 1,000 feet apart. That structure is still carrying traffic between Wheeling and Bridgeport, Ohio.

Three years after the Wheeling bridge went up, the B&O Railroad reached the Ohio River at Wheeling, a foreshadowing of eclipse. Railroads were cheaper and faster than stagecoaches and Conestogas, and for commercial traffic the National Road fell by the wayside. Officially, the Road continued to connect Cumberland to Vandalia, Illinois, but traffic along it was mostly local, and states were paying less attention to road maintenance.

By the late 1870s, the National Road had faded from national awareness. In 1879, Harper’s magazine chartered a coach and sent reporters along the route through Maryland to research and write what amounted to an obituary for the venerable highway. The resulting article characterizes town after town as sleepy and populated by old-timers wallowing in the past. In places forest was overtaking the road.

Then came two-wheelers. The modern bicycle’s introduction in the late 1880s spawned a nationwide call for better roads not just in towns but between them. This Good Roads movement in time replicated itself among owners of vehicles powered by internal combustion engines. When the Model T puttered onto the market, roads returned to the spotlight. By 1911 civic boosters and promoters were sketching nationwide highway networks

fancifully characterized as “auto trails.” That year in Missouri, Elizabeth Gentry, chair of a local Good Roads committee, proposed combining the National Road with the much older but less intensely developed Santa Fe Trail into a cross-country highway called the National Old Trails Road, to be identified by red white and blue stripes painted on poles studding its length between Washington, DC, and San Francisco. The National Old Trails Road was legitimate—in 1926, Harry Truman headed the association that sponsored the highway—but other auto trails were bogus. Grifters would blow into a town, hornswoggle officials and businesses into paying to guarantee that a road would come through, and vanish with the boodle.

In 1916 Congress passed the first highway appropriations bill since the measure funding the National Road. The U.S. Department of Agriculture was to disburse $75 million to match state funding for road improvements.

By the mid-1920s, highway officials realized the country needed to replace its freewheeling patchwork of auto trails with a system under government oversight and having more administrative structure. In 1926, the American Association of State Highway Officials chose the USDA’s six-pointed shield as the badge for national routes designated not with names but numbers. Arteries running east/west would carry even numbers; north/south, odd. Numerical designations ending in ‘0’ and ‘1’ would indicate primary routes. The National Road officially became U.S. Route 40.

Under the federal aegis, improvements came rapidly, especially in the 1930s, with the rise of the New Deal, whose programs included road maintenance that encouraged use and development along the National Road. During the Depression, the U.S. Resettlement Administration assigned artist Ben Shahn to photograph Route 40’s people and places. Shahn’s portfolio depicts a neatly paved brick and concrete road with early examples of the billboards, service stations, and motels that have figured in highway life since.

This second heyday of the National Road was almost as short-lived as the first. After World War II, with development of the interstate highway system, Interstate Highways 70 and 68 assumed the National Road’s role in long-distance travel. However, the interstates mostly parallel the National Road, and the original route remains along much of its length. The National Road abides, carrying travelers over ground trod by horses and oxen pulling Conestoga wagons and stagecoaches along America’s first great highway.

[hr]

Road to Nowhere

In 1755, a British force left from Alexandria, Virginia, to attack French Fort Duquesne. Major General Edward Braddock and his troops built the first leg of what is now the National Road. In Braddock’s Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution, historian David Preston addresses that project:

…Braddock’s Campaign was unprecedented for its mountainous character—“surely such a one was never undertaken before,” Major William Sparke believed. The first challenge was conquering the Appalachian Mountains and the nearly 125 miles between Forts Cumberland and Duquesne. Men and horses would face exhaustion and defeat at the hands of geographical forces, even before they might challenge French and Indian foes. It is difficult to exaggerate the power required to overcome these obstacles. The weapons were axes, shovels, whipsaws, wagoners’ whips, block and tackle, and blasting powder. The mountains, rocks, boulders, forests, ascents,

descents, rivers, streams, and swamps that these men and animals confronted must have seemed insurmountable. Traces of Braddock’s road are primary sources, testifying to the laborers’ toil and engineers’ logic. In addition, the British had to be entirely self-sufficient during the march, while taking enough supplies to sustain them once in the Ohio Valley. An eighteenth-century Royal Navy admiral employed a striking nautical metaphor to describe the advance of a British field army into the interior of America: it was like “the passage of a ship through the sea whose track is soon lost.” The land, like the sea, threatened to swallow up the army immediately after its departure from Fort Cumberland.

Building a twelve-foot-wide wagon road over the consecutive mountain ridges tapped an extraordinary range of skills and occupations. Sawyers, or “hatchet men,” wearing leather aprons, cut swaths through old growth timber. Blacksmiths were constantly sharpening axes, saws, and tools. Miners used gunpowder to blast through boulders and rocks larger than themselves. Diggers graded and leveled the roads. Teamsters and wheelwrights repaired the wagons’ axles and wheels, and British military engineers had to make quick topographical choices as they laid out the road ahead. Each day was an exhausting ordeal of “cutting, digging, and Bridging,” and various degrees of blowing rock, as engineer Harry Gordon described the roadwork in his Sketch of General Braddock’s March. Already a seasoned hand at colonial roadbuilding in 1755, Deputy Quarter Master General Sir John St. Clair knew the importance of tools and the need for lots of them. In April, when St. Clair was working on the roads around Cacapon, a stop on the way to Fort Cumberland, he had had the foresight to write Braddock’s aide de camp, Lieutenant Robert Orme, to employ blacksmiths around Frederick, Maryland, to produce more basic tools and equipment that St. Clair knew would be necessary: 100 “felling axes,” 12 whipsaws, and three sets of miners’ tools for “breaking and blowing rock.” After a year’s service in America, St. Clair was even more convinced that “the proportion of Entrenching Tools made out for Service in Europe will by no means answer for America.” Referring to the paltry number of such tools sent with Braddock’s troops from Ireland, St. Clair reminded his superiors that “one hundred felling Axes were sent out Last, when one Thousand wou’d have been too small a number for the work we had to do: digging is the great Work in Europe as cutting is here.”