It would be a relatively simple task for movie buffs to cite the best films on humanity’s more recent conflicts (Vietnam, Korea, both world wars). More difficult is to name good films from the distant era of Napoléon, which too many people know only from long-ago history classes or books. Yet in the best of these films, the sheer drama of the man and the days he shaped come brilliantly alive.

In compiling the 10 key titles, I’ve avoided miniseries or films running longer than four hours. I have included films portraying the French Revolution, as by most accounts, this seismic event made the ascent of the driven though diminutive Corsican native possible. Here then, in chronological order, is my own “short list” of Napoleonic-era films.

Napoléon (1927)

French director Abel Gance’s five-hour masterpiece, restored in 1981 by film historian Kevin Brownlow at Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios, remains a stunning achievement, both of storytelling and pioneering cinematic technique. Meant to be the first of a six-part series, the film ends in 1797, as the 28-year-old soldier’s star is rising (he would not crown himself emperor for another seven years).

A justly famous opening snowball fight sequence takes us back to Napoléon’s early days in a French military school. Though the boy is clearly branded as an outsider, pupils and teachers alike take note of the fearlessness housed in his small frame. Later, after a final break from his homeland of Corsica, Napoléon resolves to become truly French and advance the country’s cause by arms wherever possible. This he does, fighting right beside his men, straight through to his breakthrough campaign for Italy.

In the title role, Albert Dieudonné is positively mesmeric, only amplifying the impact of Gance’s magic camera. Watch, in particular, for Gance’s superimposed images and use of three cameras side by side, which in effect anticipated CinemaScope by decades. Surprisingly, the film was not fully appreciated on release, so Gance was unable to get backing for his full series, though he would return to the Napoléon theme several times, to lesser effect. (Video only, silent with French intertitles.)

A Tale of Two Cities (1935)

During the upheaval of the French Revolution, world-weary London barrister Sydney Carton (Ronald Colman) falls secretly in love with Gallic beauty Lucie Manette (Elizabeth Allan), who comes to regard him as a close confidante. When Lucie decides to marry Charles Darnay, nephew of a tyrannical French marquis, Carton is crushed. But he gets a chance to prove his love when the aristocratic Darnay is arrested in Paris and sentenced to die.

From the golden days of the Hollywood studio system, director Jack Conway’s rich, peerless adaptation of Charles Dickens’ famous novel succeeds on the merits of lavish production design and exquisite, tone-perfect acting from the entire cast, overseen by MGM honcho David O. Selznick. Colman’s crowning screen performance as the cynical, boozing Carton and solid support from the likes of Basil Rathbone and Edna May Oliver make this a sumptuous gem that refuses to grow old.

That Hamilton Woman (1941)

Reputedly Winston Churchill’s favorite film, producer Alexander Korda’s British production showcases the chemistry between then real-life partners Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in portraying the scandalous romance between Admiral Horatio Nelson, one of Britain’s leading naval heroes, and Lady Emma Hamilton. Why scandalous? Because each was married to another—he to a wife back in Britain he barely saw, she to a much older man who was Britain’s ambassador to Naples.

As the Napoleonic wars heated up at sea, so did their romance, with Lady Hamilton eventually living openly with Nelson. For reasons both personal and professional, Nelson was kept largely afloat, away from his beloved. After a brief respite with Emma in 1805, he received orders to set sail for Spain and there would forever be celebrated for his heroic death while defeating Napoléon’s fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar.

The movie is as much romance as war film but works admirably on both levels. In Britain it was considered one of the more effective World War II propaganda films. (Video only.)

Damn the Defiant! (1962)

During the Napoleonic wars, Captain Crawford (Alec Guinness) runs HMS Defiant, a tight ship. What the fairminded Crawford doesn’t count on in his latest voyage is the new second-in-command, 1st Lt. Scott-Padget (Dirk Bogarde), a young martinet in the making with friends in high places back at the admiralty. The cruel Scott-Padget undermines Crawford’s more humane instincts at every turn, turning a crew already disgruntled at deplorable conditions into a mutinous horde.

This salty, overlooked British entry undeniably fires on all cylinders. Lewis Gilbert (who would direct the original Alfie and three Bond entries) displays a sure hand, with first-rate actors Guinness and a deliciously hateful Bogarde crossing verbal swords with gusto. Meanwhile, gifted character actor Anthony Quayle organizes the men belowdecks. The denouement is worth waiting for, with vibrant color footage recreating these beautiful ships in full battle mode. (Released in Great Britain as HMS Defiant; released in the U.S. as Damn the Defiant!)

Billy Budd (1962)

On a British warship arrayed against the French and helmed by Captain Edwin Fairfax Vere (Peter Ustinov), handsome, illiterate sailor Billy Budd (Terence Stamp, in his film debut) enjoys the bonhomie of his fellow seamen but unwittingly makes an enemy of sadistic master-at-arms John Claggart (Robert Ryan), who considers Billy’s good-natured smile and inarticulate demeanor a form of insubordination. Claggart uses his position to turn the tide of goodwill against Billy.

Set in 1797 and based on Herman Melville’s novella, Ustinov’s sterling big-screen version of Billy Budd features a memorably fierce turn by Ryan and an almost angelic one by Stamp as the pure, fair-haired innocent. Gorgeously shot in Spanish waters, Billy Budd is an intense, heartbreaking tale of good and evil grappling on the high seas.

Love and Death (1975)

As the Napoleonic juggernaut extends to Russia, noted intellectual and coward Boris Grushenko (Woody Allen) occupies himself with adoring the beautiful Sonja (Diane Keaton), but she only has eyes for Boris’ mind. Sonja finally agrees to marry him, however, and then enlists Boris in a daring scheme to assassinate Napoléon. Of course, all these shenanigans only confirm the utter futility of human existence—but in Woody’s worldview, it’s still preferable to being dead!

Director/writer/star Allen hits dizzying comedic heights in this zany spoof of Russian literature. Keaton continues to build on her distinctively ditzy persona as the idealistic but scattered Sonja. Populated with assorted colorful types (notably a brief but hilarious turn by character actor James Tolkan as a randy Napoléon), the film’s sustained hilarity makes this a favorite Woody Allen outing.

The Duellists (1977)

In Ridley Scott’s directorial debut, based on a Joseph Conrad story, we are in the heat of the Napoleonic campaigns, following the intertwining lives of two French officers, one intent on killing the other via the “honorable” custom of dueling.

The action starts when the unlucky D’Hubert (Keith Carradine) is ordered to seek out serial duelist Feraud (Harvey Keitel) and place him under house arrest for skewering the local mayor’s son. While clearly a skilled and fearless soldier, the mercurial Feraud seems more than slightly unhinged. Viewing D’Hubert’s action with burning hostility, he throws down the gauntlet, summoning him to a duel then and there. As an officer and gentleman, D’Hubert has no recourse but to accept, but the two men are so well-matched that neither can finish the other off. The same challenge from Feraud then recurs anytime the two soldiers cross paths over the ensuing years.

This ravishing, atmospheric film rises above the unusual casting of two dyed-in-the-wool American actors in the central roles, buoyed by excellent support from British players Albert Finney, Edward Fox and Tom Conti. Among the two leads (despite lack of accent), Keitel wins top laurels, as he imbues his Feraud with a truly frightening malevolence. Yet overall, the real star here is Scott’s sumptuous filming style, which won him the Best First Work award at Cannes. (The director would quickly move on to such mainstream fare as Alien and Blade Runner).

The Scarlet Pimpernel (1982)

To London society, foppish English aristocrat Sir Percy Blakeney (Anthony Andrews) appears well acquainted with powdered wigs, poetry and not much more, even to lovely paramour Marguerite (Jane Seymour). But in reality, he is the Scarlet Pimpernel, a cloak-and-dagger swashbuckler who has secretly been entering France to free nobles condemned to the chopping block in the wake of the Revolution. Now the French have dispatched underhanded ambassador Paul Chauvelin (Ian McKellen) to ferret out this mischievous masked hero.

Set during Maximilien Robespierre’s head-rolling Reign of Terror, this rousing remake of Harold Young’s 1934 original has all the haute glamour, period flair and zingy dialogue you would expect from an old-fashioned adventure tale. Under Clive Donner’s assured direction, Andrews scores in the central role as the dandy with two identities. Seymour’s elegance plays well off his innocuous Percy, while McKellen, in a dastardly turn, makes a goading nemesis. The 1934 classic, also highly recommended, runs a half hour shorter and stars the venerable Leslie Howard, Merle Oberon and Raymond Massey. (The ’34 version is available only on video.)

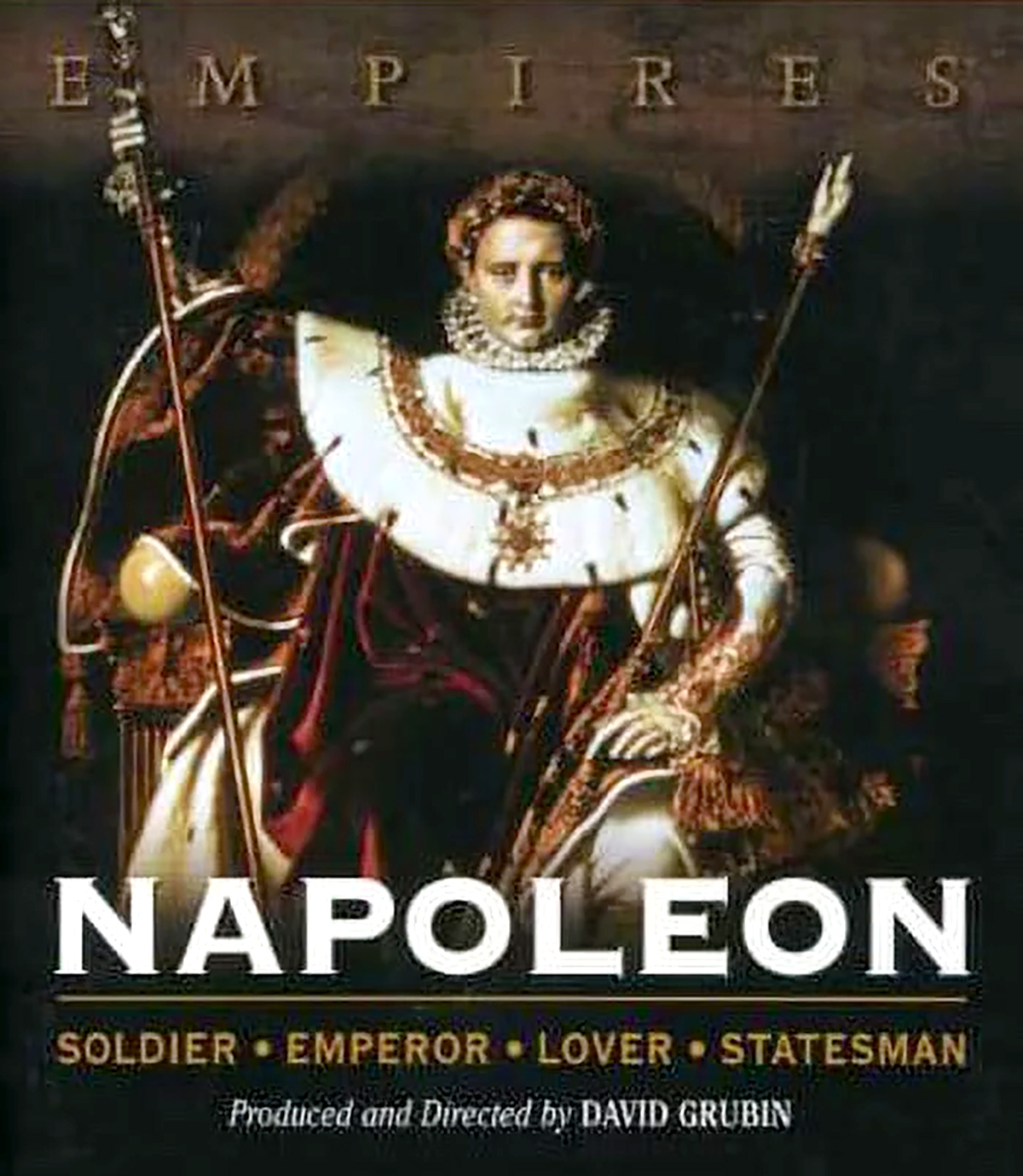

Napoléon (2000)

For a truly comprehensive view of Napoléon’s rise and fall, look no further than this first-rate documentary, directed by David Grubin under the auspices of PBS and ably narrated by eminent historian and author David McCullough. This insightful feature runs four hours but can readily be viewed in two installments.

Its chief virtue is a keen sense of balance, mixing historical commentary with exciting battle reenactments and blending description of the soldier/emperor’s military fortunes with an involving perspective of the man himself. We learn about Bonaparte’s early feelings of isolation and conflicted loyalties, his increasing sense of infallibility as his fame grew, and his unfettered passion for Josephine (he wrote to her constantly, often on the verge of battle). If you want to brush up on your Napoleonic history and have fun doing it, don’t miss this film.

Master and Commander (2003)

As the Napoleonic wars pit English against French at sea, Captain Jack Aubrey (Russell Crowe) commands the British frigate HMS Surprise. Aubrey’s mission is to track down and sink Acheron, a much larger and better-equipped French ship. Even as the vessel and crew endure the destruction of an enemy sneak attack and the ravages of inclement weather, Aubrey is unwavering in his duty.

Based on Patrick O’Brian’s renowned seafaring adventure novels, Peter Weir’s Master delivers an intimate, seemingly accurate portrayal of rugged life on the high seas, limited in creature comforts but rich in camaraderie. Crowe makes a commanding but compassionate hero, and his friendship with ship doctor and scientist Stephen Maturin (Paul Bettany), who’d like Aubrey to slow down so he can collect samples of unknown species, provides some interesting character byplay between full-bore battle sequences. In all, Master is a flavorful, bracing adventure, suitable for family viewing.

War and Peace, to many informed history buffs, would seem a natural for this list. It does not appear here because the 1956 Hollywood version (starring Audrey Hepburn and Henry Fonda) is very good in parts but fatally flawed overall, particularly in its miscasting of Fonda and a wooden Mel Ferrer (then Hepburn’s husband) as Pierre Bezukhov and Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, respectively. For Tolstoy purists, director Sergei Bondarchuk’s legendary 1968 Russian version, Voyna i mir, which garnered the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, does fuller justice to the author’s masterwork, but be advised—it runs seven hours! Bondarchuk portrayed the emperor’s downfall just two years later in Waterloo, starring Rod Steiger as Napoléon, but that feature did not scale the heights of the director’s earlier epic, which took five years and $100 million to complete.

For further information, John Farr recommends his Web site [www.moviesbyfarr.com] and his blog [http://johnfarr.type pad.com].

Originally published in the December 2007 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.