A team of Tuskegee Airmen took top honors at the 1949 Air Force gunnery meet, only to have their trophy mysteriously disappear for 47 years.

Everybody knows the story of the Tuskegee Airmen—how they blew through the color barrier and became World War II’s only American black pilots and ground crews, how they flew hundreds of successful bomber escort missions with their red-tail P-51s, how they went home at war’s end and found racism in the U.S. still alive and well. End of story.

Actually, it isn’t. One of the least-known aspects of the Tuskegee saga is that their 332nd Fighter Group was reactivated in 1947, and continued to fly until June 1949 with a solid cadre of peacetime African-American pilots, most of whom were combat veterans, and ground support personnel. And most stunningly, that in May 1949 three black pilots from the 332nd took first place, as a team, at the U.S. Air Force’s very first postwar fighter weapons meet. It was called the United States Continental Gunnery Meet, and it would go on to become the famous USAF William Tell competition. The 332nd team was crowned the Air Force’s champion piston-engine gunnery, rocketry and fighter-bomber experts. (There was a separate division for jets—Lockheed F-80s and Republic F-84s in ’49.)

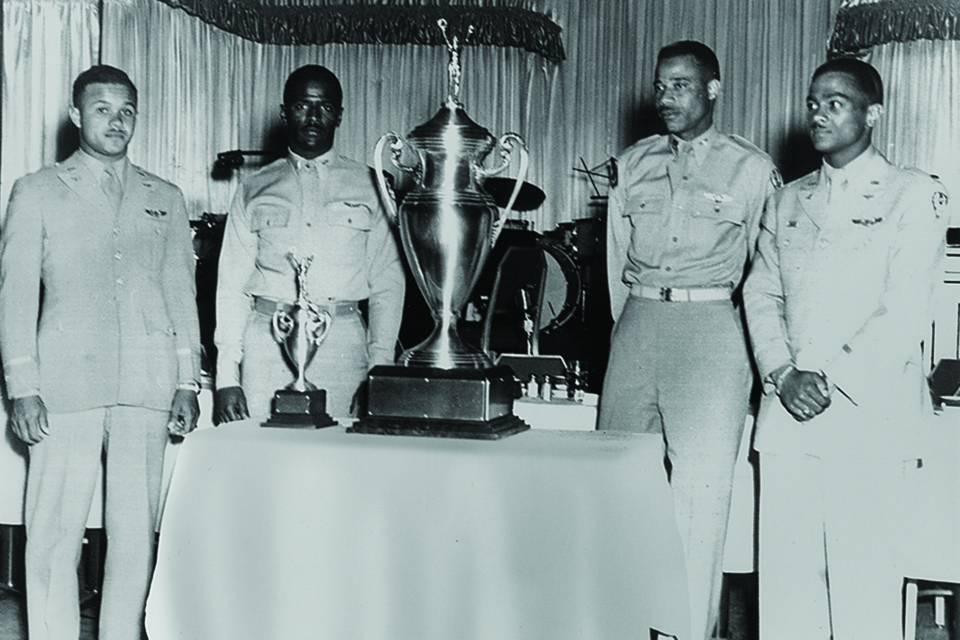

Unfortunately, the Tuskegee team’s trophy went missing, and until 1995 the winner in the propeller-driven division at that prestigious meet was listed in Air Force records as “unknown.” Some say it was a typical military screw-up, no harm intended. Others point to it as an obvious example of still-smoldering racism; the Air Force couldn’t bear to admit that “a bunch of Negroes” had won the competition.

It was stovepipe hot in Las Vegas in May 1949, but “the weather was perfect,” recalled Harry Stewart, a retired engineer and natural gas pipeline company executive from Bloomfield, Mich. Stewart was one of four members of the Tuskegee team. “The missions started very early in the morning—about 6 o’clock, because the thermals in the desert got pretty bad as the day went on, especially if you were doing low-level skip bombing or strafing.”

Stewart, who retired from the Air Force Reserves as a lieutenant colonel, was then a first lieutenant. His teammates were 1st Lt. James Harvey (also alive today) and Captain Alva Temple, plus one alternate in case a substitute pilot was needed, 1st Lt. Halbert Alexander.“There were six events,” said Stewart. “Aerial gunnery at 10,000 and 20,000 feet, skip bombing, rocketry, dive bombing and panel gunnery—strafing a 10-by-10-foot panel on the ground. In the aerial gunnery, we were shooting at a sleeve towed by a Douglas A-20.”

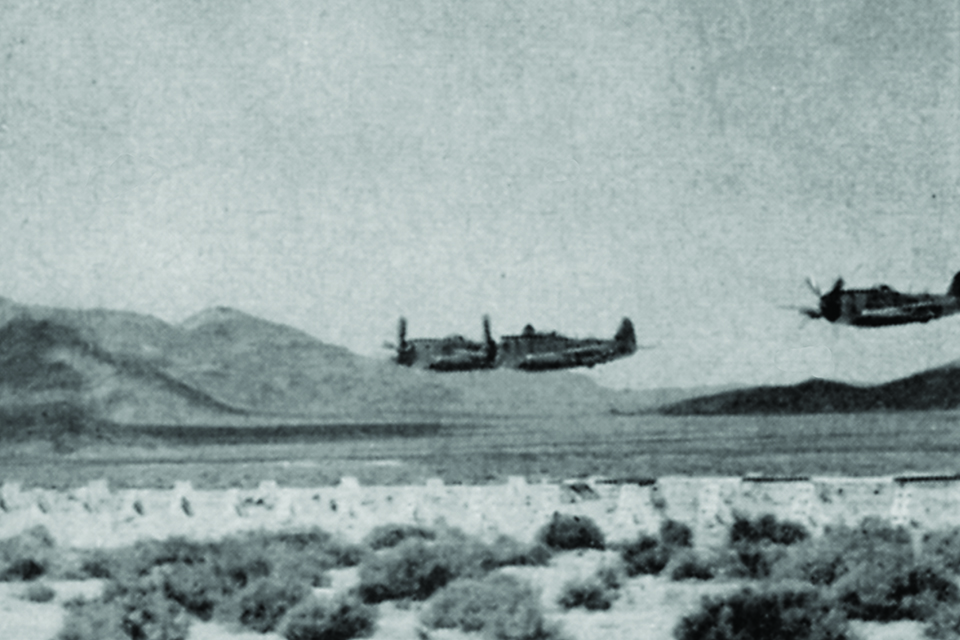

The 332nd’s airplanes were Republic P-47N Thunderbolts (redesignated F-47s), and James Harvey thinks they put the Tuskegee Airmen at a bit of a disadvantage against the North American F-51s, F-82 Twin Mustangs and Northrop F-61 Black Widows the other units flew.“The P-47 was obsolete, period,” said Harvey, of Denver, who had an extensive USAF career that among other high points made him the first black jet pilot to fly combat over Korea. “The Air Force was getting rid of them, going into jets. The Thunderbolts were going to the Air National Guard. When they reactivated the 332nd in ’47, they picked up P-47Ns out of storage in Oklahoma City and brought them to Lockbourne Air Force Base, in Ohio, where we were stationed. My job for a long time was ferrying P-47s.”

Stewart, however, was fond of the old Jug. “It was just as good for what we were doing with it as the P-51,” he said. “The P-47N was the final model. They were designed specifically for the war in the Pacific, with a souped-up engine, fuel tanks in the wings and they even had an autopilot. They had a range of 13 hours and were designed to fly from Okinawa to the Japanese mainland, escorting B-29s. That was probably going to be the 332nd’s next mission, had the war not ended.”

One thing the P-47 was particularly good at was skip bombing, since it had found its métier in Europe as a fighter-bomber. “We had the most fun with the skip bombing,” Harvey said. “We had a perfect score. Three missions, two bombs per plane. No, you didn’t guess at where to skip the bomb to hit the target; we didn’t guess at anything—we were good,” he said, laughing. “We’d come in with our prop tips about a foot off the ground, and the instant the target disappeared under the nose, we’d punch off the bomb. Let it go and pull up.”

Harvey wasn’t kidding about the low altitudes. Each team was allowed to bring four airplanes, in case one of the three team planes experienced a mechanical failure, and the 332nd used their spare. “One of our pilots ran onto a stanchion that held up the skip-bombing target,” said Stewart. “It was an iron pipe, and it ripped a hole in the belly of the P-47. That plane had to be taken out of action.”

Both Stewart and Harvey credited their ground crews as equal winners of the competition.“It was a competition between the support crews as well as the pilots,” Stewart said. “It was up to them to keep those airplanes tuned so we could meet each of our missions. If the ground crews couldn’t keep up, we’d have to default. We came back from our missions about noon, and the ground crews started to work on the airplanes. They worked late into the evening to get those ships ready for us the next morning.” Stewart explained that the guns were “harmonized” after every flight, carefully bore-sighted and aligned to provide the exact bullet pattern that each pilot wanted, in case vibration or recoil had slightly displaced the guns. (The F-47s had eight .50-caliber guns, and since the F-51s and F-82s had only six, two of each Jug’s .50-cals were disarmed to even the odds.)

“Our ground crews were so good that when they broke our fighter group up in ’49 and scattered us to squadrons all over the world, our group commander got more requests for his maintenance people than anybody else,” recalled Harvey. “They were the best in the Air Force.”

Oddly, Harvey and Stewart remember the mood of the meet entirely differently, which perhaps shows that racism can be perceived and imagined, as well as being irrefutably experienced.

“We had no contact with the white pilots,” Harvey said, his voice making it clear that he’s still simmering. “They just ignored us. Nobody talked to us, period. After the weapons meet, they had this big banquet at the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas. They took our pictures with the trophy, and they told us goodbye. They were having a big to-do for the winners of the meet, but we didn’t get to participate.”

“No, I don’t recall that at all,” said Stewart. “The white pilots were polite, cordial, not condescending. We didn’t do too much socializing with them, though we did with our brother fighter pilots from the Ninth Air Force, the 4th Fighter Group. They were white, flying F-80s in the jet division. We had trained at some of the same fields, so we had an ongoing rapport with one another.” He takes pride in the fact that the 4th Group won the jet class, making it a clean sweep for the Ninth Air Force.

“It wasn’t a coincidence that the two class winners came from the same air force,” Stewart continued. “It was a tactical air force, and we were constantly training. We spent two months twice a year down at Eglin AFB, in Florida, practicing gunnery and ground support. When we competed against the rest of those guys, the extent of our training came through. I don’t think it was any inherent superiority.

“As I remember, we went to the final banquet. As far as on-base activities went, in no way were we excluded from anything.” But Las Vegas itself was not so accommodating; a group of 332nd enlisted personnel had been kicked out of the Flamingo—no blacks allowed—days earlier.

Stewart’s memories are given added weight by his account of the competition’s one tragedy: “We had a double fatality out there, in an F-82, and one of them was one of our crew chiefs, a fellow named Austin. He had asked the F-82 pilot, who was white, if he could take a ride with him in the empty second cockpit. It was the guy’s first dive-bombing attempt, and he failed to pull out in time.” Horrific as the outcome was, a white officer pilot agreeing to take a black enlisted man for a joyride hardly speaks of racial discrimination.

Stewart also pointed out that though the fighter weapons meet was a team competition, the highest-scoring individual pilot was white. “We were outgunned in the strafing category by a P-51,” he admitted. “Our points leader at the time was Captain Alva Temple. He was amassing a tremendous score until panel gunnery came along. Temple was set to be the top gun until this fellow from the 82nd Fighter Group named [1st Lt. William W.] Crawford came along, and he shot an uncanny score on strafing. To give credit where it’s due, Crawford got the top individual score, and Temple came in second.”

Through the efforts of former Tuskegee Airmen and other enthusiasts, the 1949 U.S. Continental Gunnery Meet trophy was finally unearthed, in 1996, in a storeroom at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force. It is currently on permanent display at the museum. “There’s a story there that we’ll never know,” said Stewart. “Some people attribute it to racial bias, but I don’t feel that way myself. I think it was just a military screw-up.”

After the gunnery meet, Harvey went on to fly F-80s out of Misawa AFB, in Japan, during the Korean War. The story of his arrival at Misawa recalls a classic line from the film In the Heat of the Night, which starred Sidney Poitier as Virgil Tibbs, a Philadelphia police detective caught in the middle of a murder investigation in a small Mississippi town. “So what do they call you up there in Philadelphia?” the redneck sheriff asks Poitier. “They call me Mister Tibbs,” Poitier snarls. When Harvey arrived at his new unit, the wing commander, who had never in his life seen a black pilot, said, “So what should we call you?”

“How about Lieutenant Harvey,” he said.

Even James Harvey might not have believed that during his lifetime there would be a man who could say, “You can call me President Obama.” The Tuskegee Airmen played a substantial part in making sure that would happen.

Thirteen months before the Las Vegas fighter weapons meet, Lieutenant Harry Stewart had already established his own small niche in Air Force history. Returning from Shaw AFB in South Carolina to the 332nd Fighter Group’s base in Ohio, VFR on top of solid clouds, Stewart ran into a boomer—a thunderstorm that overwhelmed his ability to fly an F-47 on instruments while dealing with lightning, express-elevator air currents and rain pounding his canopy. Stewart said the hell with it, cranked the canopy back and bailed out. He hit the vertical stabilizer hard, shattering one leg, pulled the D-ring and floated down through the undercast.

“When I came out of the clouds, I saw a couple of hills and a valley, and I tried to steer the chute like I remembered being told you were supposed to do, toward what looked like a good landing spot,” Stewart said. “I nearly collapsed the chute and decided to leave well enough alone. Landed in some pine trees and ended up hanging about two feet above the ground. Got myself down and crawled under a rock overhang. It was still raining hard.”

Stewart had landed in Butcher Hollow, Ky. (Cue Loretta Lynn: “Well, I was born a coal miner’s daughter, in a cabin on a hill in Butcher Holler…”) His empty airplane hit the ground about 100 yards from Lynn’s birthplace.

In 1948, in hardscrabble rural Kentucky, for a black man this wasn’t much different from landing behind enemy lines. In fact, the incredible rumor eventually spread that “a Negro” had stolen a B-52 and was shot down by F-84 Thunderjets while making a bombing run on the town. “It wasn’t long before I heard a voice hallo-ing, and a man showed up on a horse. His daughter had seen my parachute. When he saw me, he took a deep breath, and so did I, and we stared at each other awhile. He took me to his farm on another horse he’d brought along, and his wife was out in the yard washing clothes in a big cauldron.

“She went into the house, came out with a clean white sheet and began tearing it into bandages. It was quite a gesture on her part, since I’m sure they didn’t have any spare sheets. She washed my leg and bandaged it.

“I was in pain at the time, and her husband came out of the house with a glass of what looked like water. I’d given up drinking for Lent—I came down on Palm Sunday—and I put the glass to my nose and smelled the moonshine, gave it back to him and said no thanks. He gave me a hard look and said, ‘You better drink that.’ I didn’t know if it was a threat or because he thought I needed it for the pain, but I wasn’t going to argue with him. I downed it, and I don’t think any quantity of cocaine or morphine could have done better for the hurt.”

Some years ago, Stewart was invited back to Butcher Hollow—the township is actually named Van Lear—as the marshal of the Homecoming Day parade. “I met Loretta Lynn’s family, went out to the home where she was born. They treated me royally.”

For the past two years, Stephan Wilkinson has been a youth mentor for the Maj. Gen. Irene Trowell-Harris Chapter of the Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. He teaches classes in flying, aviation history and writing in the chapter’s Red Tail Youth Flying Program at Stewart Airport, in Newburgh, N.Y. For more on the chapter, which not only operates the flying program with a Cessna 172 but also awards $10,000 annually in tuition-assistance grants to college-bound Hudson Valley high school seniors, go to www.tai-ny.org. James Harvey has an extensive website dealing with the Airmen’s involvement in the gunnery competition, www.tuskegeetopgun.com.

Originally published in the March 2012 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.