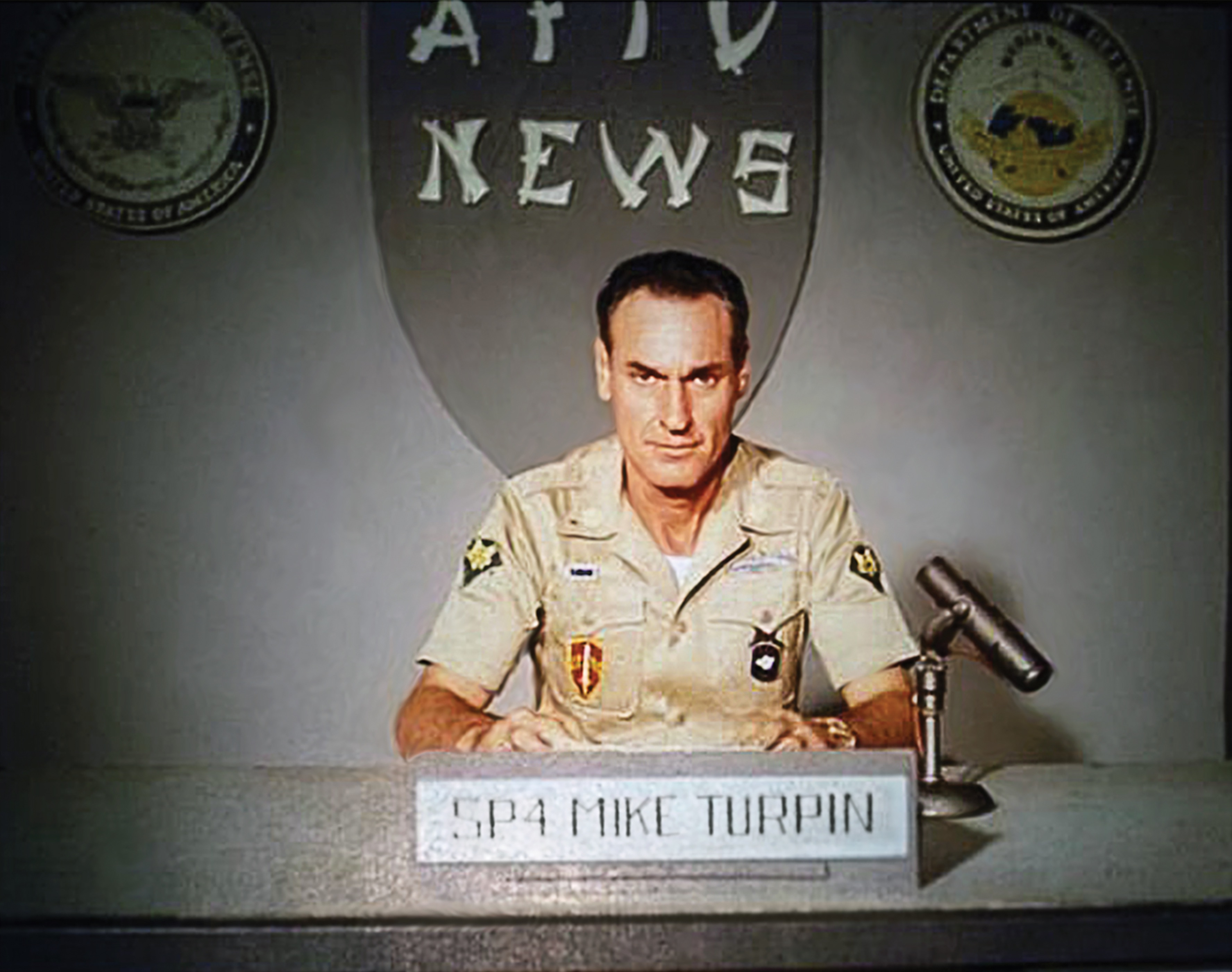

Nothing seemed unusual about Army Spc. 4 Mike Turpin. He was a respected TV newscaster during his time at American Forces Vietnam Network, the military’s radio and television service for U.S. forces. When Turpin went on the air as a new TV anchor in 1967, “he had a new uniform and looked spic and span,” said John Mikesch, an Army specialist 5 and technical director for Turpin’s newscasts. “He had a mature, experienced presentation. He was perfect.” To most people who knew him, Turpin hardly seemed like a person who would die under mysterious circumstances, yet that is what happened in 1972 after he left the military and strangely returned to Vietnam.

Nearly 50 years later, the mystery remains unsolved.

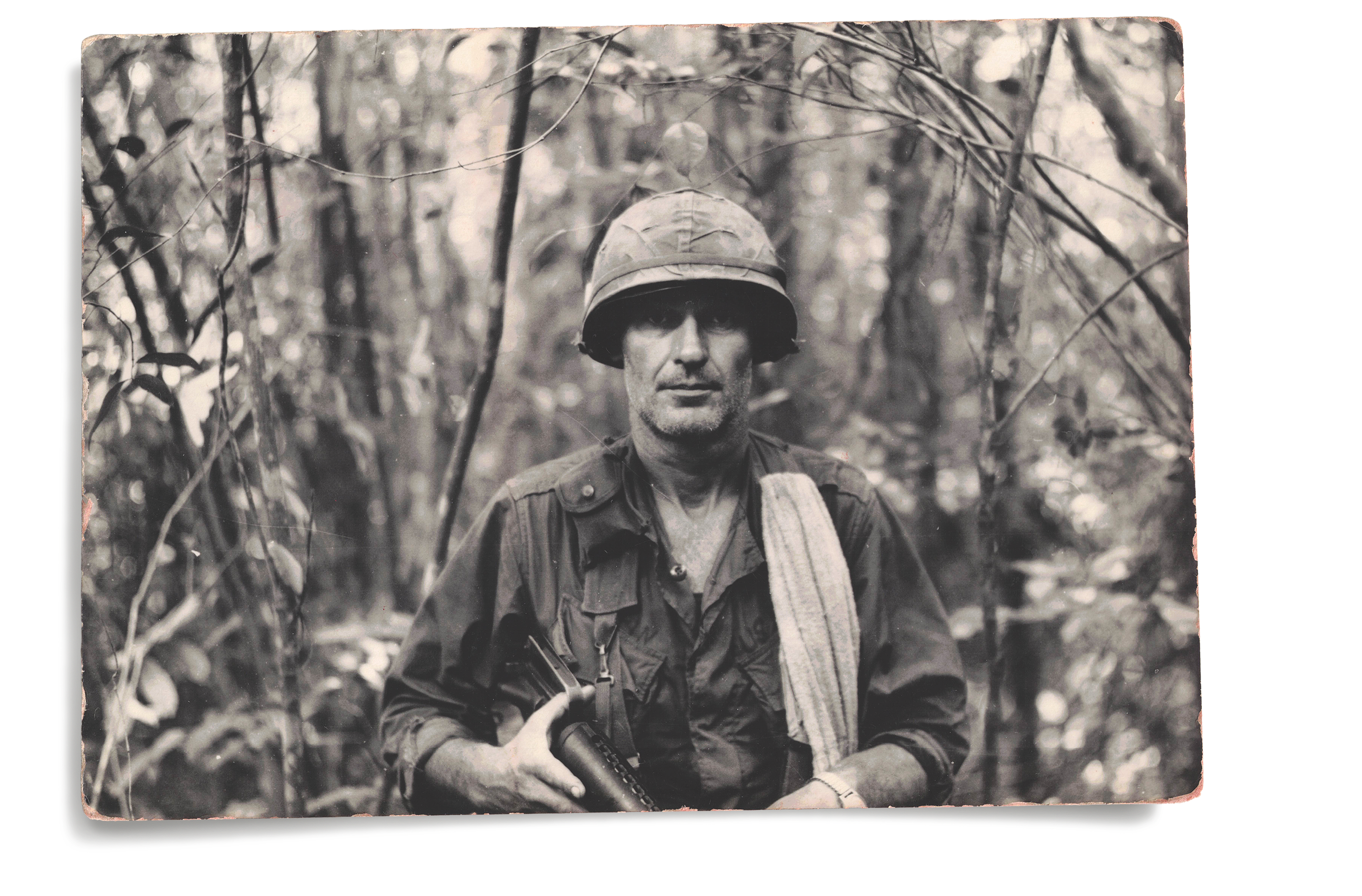

Off-camera, Turpin, who spoke at least five languages, led a life that was a perilous concoction of adventure and danger. He had previously served in Vietnam with the 1st Infantry Division and received a Purple Heart, Silver Star and Bronze Star. Turpin joined the Merchant Marine at age 16 in 1944 but changed course the next year and enlisted in the Army in April 1945. He served in Korea, where he suffered a head laceration and earned a Bronze Star. He was discharged from the Army in 1968.

Turpin, who went by “Mike” but whose given name was Ira Leslie Turpin, was born Jan. 29, 1928, in Gary, Indiana. He had five marriages, and four of them broke up. The last three wives are deceased, and the first two are believed to be dead. He had five biological children and one stepdaughter.

When Turpin died, officially in April 1972 at age 44, he was in Vietnam as a civilian. It’s not clear what he was doing there. Even more puzzling is his death. There are multiple theories of what happened.

Trouble at International House

After he left the military in 1968, Turpin ran a small bookstore at the International House, a popular downtown Saigon social club for foreign civilians.

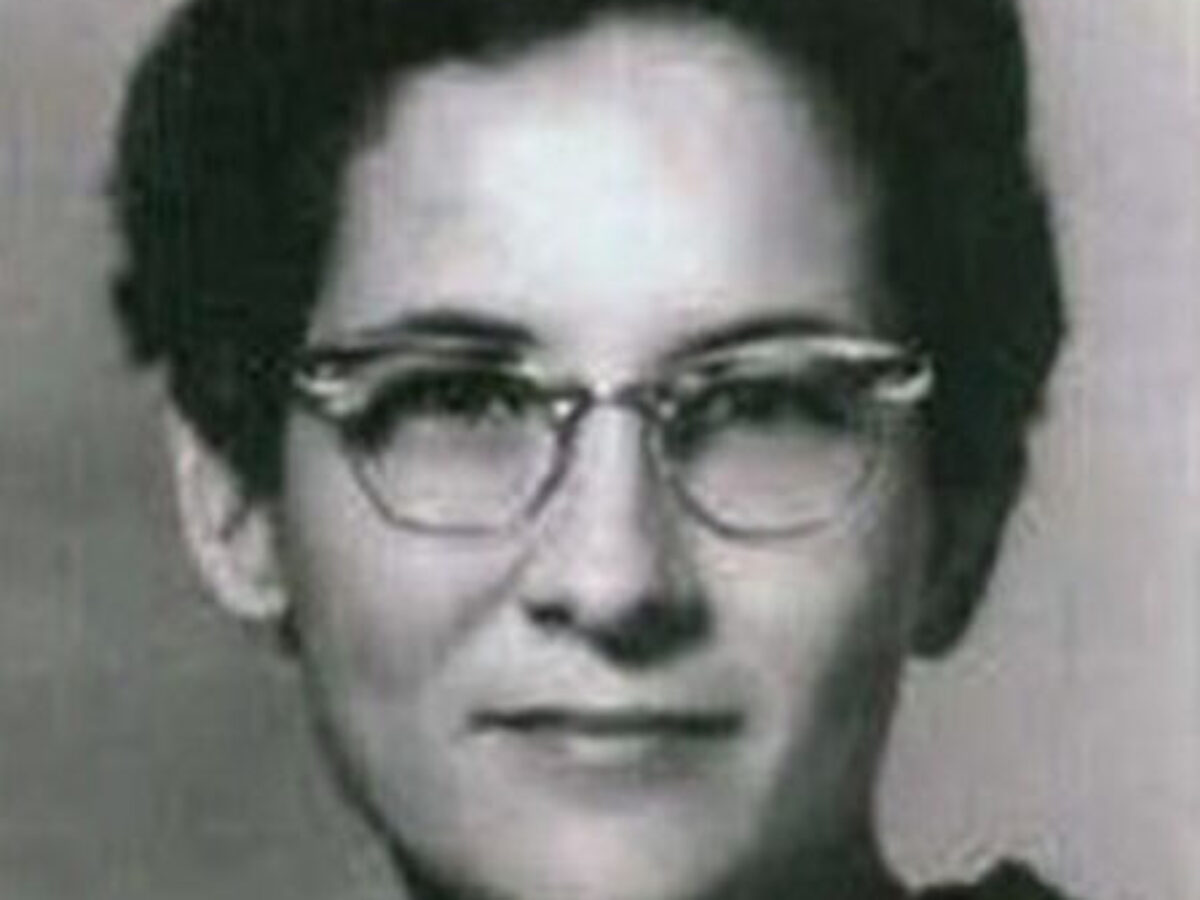

That same year, he married Kyong Ui, the International House’s chief accountant, whom he had met while still in the service.

A Korean native, she was known as Kim to everyone but Turpin, who called her Lily. She had a young daughter, also born in Korea. The wedding reception took place in the club’s banquet room. Lily had become Turpin’s fifth wife.

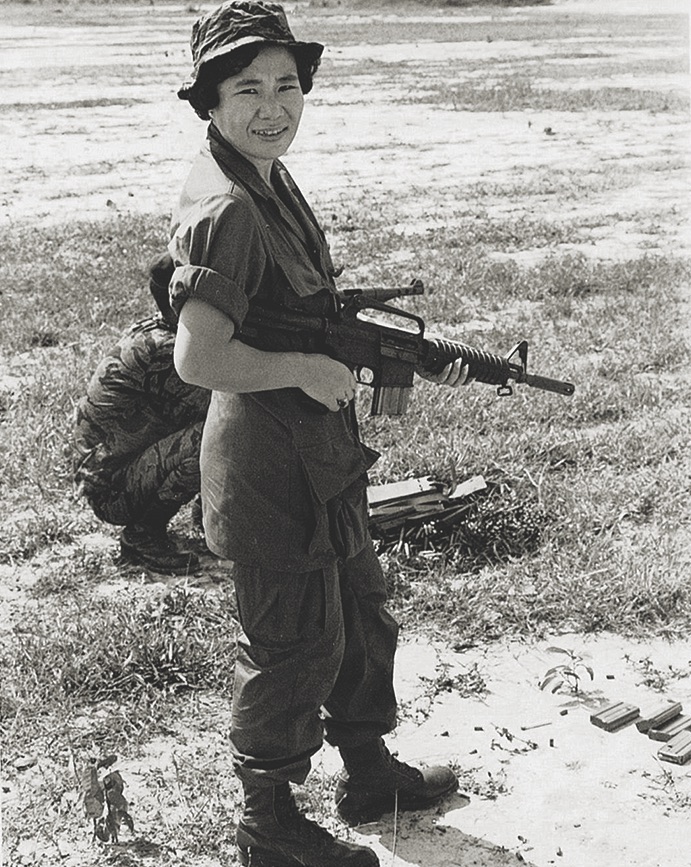

Customers at the International House tended to be “high military people, high-ranking Vietnamese people, Indian people, Arab people, French people,” said Doris Hochberger, Lily’s daughter, who used to go there with her mother, who died in 1998.

The International House had several thousand members, according to a wartime column by Daniel Cameron in The Saigon Post. “You paid a $20 membership fee and then ate low-priced steaks, drank the PX booze, played the slot machines and had companionship,” Cameron wrote. “Americans went there in droves,” he said.

Some U.S. officials served on the International House board and the U.S. Embassy could audit the place, but otherwise it had limited oversight.

According to Cameron, a federal grand jury indicted two managers for defrauding the U.S. government of hundreds of thousands of dollars. The club reportedly closed in 1969.

“Everybody got subpoenaed at International House,” Doris said. “Everyone had to testify, and they were leaving town.” One of her father’s friends was subpoenaed and then was killed when his helicopter blew up. Lily’s boss, also summoned, was shot while walking to work, but survived. Turpin suddenly moved Doris and Lily to Bangkok. “It seemed my dad was shipping us off to get us out,” Doris recalled.

She was too young to understand events at the time. “When I got older I always figured it had to do with money,” Doris said. “Greed. So much money went through International House. I thought it was embezzlement, money laundering. I don’t know.”

Jocelyn Turpin, the daughter of Turpin with his third wife, Joyce, was researching the family’s complicated history when she came across connections between the International House and a scam involving diamonds imported through the Post Exchange.

Clark Mollenhoff, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for The Des Moines Register in Iowa, wrote about the investigation in 1971, reporting that a global diamond trader was doing more than $1 million a month in business through the PX system. Mollenhoff explained that expensive jewelry was allegedly being sold through International House to avoid high South Vietnamese customs duties. “That central fact,” he wrote, “is at the heart of what will be one of the major scandals coming out of the Vietnam War.”

Family members believe Turpin and Lily were both subpoenaed to testify before a federal grand jury and a U.S. Senate subcommittee investigating Vietnam scandals.

“He told us he was due in court in LA later that spring [1971], but he didn’t want to go and was afraid he wasn’t going to return,” Jocelyn said. Family members aren’t certain whether Turpin and Lily were subpoenaed to testify as suspects, informants or straightforward witnesses.

There was no official allegation linking the couple to illicit activities at the International House, but the Turpins’ affluence did not go unnoticed.

“My mother had a lot of diamonds,” Doris recalled. “I mean a lot of diamonds. She had one-carat diamond earrings.” The family moved into a large residence outside Saigon about the time Turpin left the military. They had a pool, two housekeepers and a gardener. They hosted large weekend social gatherings, and up to 150 guests attended some of the barbecues, including Turpin’s friends from AFVN.

Turpin also had a virtual arsenal in his house. “In my parents’ room, under their armoires, he had AK-47 and M16 rifles, grenades, all kinds of stuff,” Doris said. Turpin also kept two handguns at home, one in his nightstand and one under the bed. He taught Doris and Lily how to shoot. “One time they used a grenade launcher on a watermelon,” Doris recalled. “It was awesome!”

Jocelyn believes Turpin might have been profiting from the black market. “Clearly, he was involved with something,” she said. “I think a lot of people wanted him dead for the information he had.”

Killed in Combat Theory

After the family moved to the United States in 1969, Turpin bought a house for his parents in Florida, a car for his family and a sports car convertible for another relative—all in cash. “Dad never wrote a check and did not have a credit card,” Doris said. Turpin took Doris on a driving vacation that covered 32 states in four months.

At one point, the family stayed at AFVN veteran Mikesch’s house in Seattle while Turpin tried unsuccessfully to find work in television. The family moved on as Turpin continued his job search, which landed him in a familiar place.

“He’d gone back to Vietnam to do some work for the military or the government,” according to information Mikesch got later from Lily and confirmed with his own contacts. “He was freelancing,” Mikesch said. “There were a lot of new weapons being developed at that time, and he got connected with people who were able to maintain these things, able to get hold of them.”

Mikesch believes that Turpin was killed in combat: “In one of those skirmishes that he was involved in they were overrun. Something went wrong . . . so that was the mystery of how it all ended.”

When Jocelyn attended a reunion and talked with Turpin’s buddies from the 1st Infantry Division, she heard speculation that her father was “military intelligence.”

Died of Natural Causes Theory

In a letter to the family, U.S. Embassy Consul General Malcolm Hallam wrote that Turpin’s landlord found the former soldier dead in his room in late April 1972.

“He was sitting in a chair dressed in pajamas with his head and upper torso slumped over . . . and his head resting on a small table,” the letter said. “There was no visible evidence of violence within the room.” Congealed blood from Turpin’s nose and mouth covered the top of the table. Vietnamese police “found no evidence of foul play,” Hallam stated.

Recommended for you

The consul general said Turpin’s friend, Larry Worth, president of Worth Co. Ltd. in Saigon, told the embassy that Turpin was unemployed and visited him the night before the body was found. Worth’s business card was in one of Turpin’s pockets. The official death certificate, signed by an Army captain at 3rd Field Hospital, lists the cause of death as “natural” and shows that no autopsy was performed.

The body was flown to Georgia where Lily and Turpin’s father, Leslie, met the plane to make the identification. Doris, 9 years old, did not go to the airport, but she remembers the adults talking afterward. They were uncertain if the body really was Turpin’s.

“Mom said it could have been anyone,” Doris recalls. “There was no embalming.”

However, a U.S. Foreign Service report on Turpin’s death says the remains were “embalmed and shipped by air to U.S.” The body was buried at Pennville, Georgia, on May 9, 1972—11 days after being discovered in the room in Vietnam.

Bar Brawl Theory

Another theory comes from former Army Spc. 5 Dick Ellis, who worked with Turpin at AFVN and ran his teleprompter for the 6 p.m. news. After Turpin left the military and returned to the United States, he “then came back to Saigon as a civilian and was shot in a bar incident, I understand,” Ellis said.

The three Turpin children I interviewed were not familiar with the bar murder story; however, they weren’t surprised. Jocelyn told me that military police once went to the home of Turpin’s parents in Georgia and told them their son “had been found in an alley badly beaten.” When Turpin was a younger man he would regularly get into bar fights, she added.

Standing over 6 feet tall, Turpin was an imposing man and gritty. Before his time at AFVN, he was a reporter and anchorman at TV station WTOP (now WUSA) in Washington, D.C. His son Matt, Jocelyn’s brother, has a newspaper clipping that shows the reporter on the other end of a news story. “There was some news conference in D.C., and he got into a brawl with another reporter, and it made the news,” Matt said.

CIA Theory

One of the most tantalizing clues about Turpin’s death came from a man who visited Lily in Florida and identified himself as “Mr. Olson.” He told Lily he was with the CIA, recalled Doris, who had been sent to her room but heard everything. “He was talking about the time in Vietnam, about International House and started talking about dad,” Doris said. “He told my mother he was murdered and shot in the head.”

From her room, Doris could see photographs Olson had brought, including an 8-by-10-inch

black-and-white print that showed a man leaning over with his head on a desk, an image similar to the scene described in the U.S. consul general’s letter. The man’s face was not visible. “It looked like it was staged,” Doris said. “It was too neat, no mess, no blood.”

Jocelyn didn’t see the photo but also thinks the death scene was staged, based on the embassy’s description of the hotel room. No identifying features were given, and the lack of an autopsy prevents other confirmation, she said.

Jocelyn has conducted a tenacious search for official records, photographs, credentials and internet corroboration.

Rather than answering questions, however, that documentation often raises new ones.

For example, personal possessions that the embassy recovered from Turpin’s room and returned to the family include clothing, his passport and items like his wristwatch and toothbrush. “I think what is unusual is what is missing,” Jocelyn said. “Where are his pipes and books? He never went without those.”

Also puzzling are two photographs the embassy returned to Turpin’s family. They show Turpin inside Andy Wong’s Chinese Sky Room nightclub in San Francisco—28 years earlier. One picture is a group photo of Turpin with about 10 men and women around a dinner table. The other snapshot shows Turpin sitting with an unidentified woman holding a cocktail.

Jocelyn asked: “Why was this gathering in a Chinatown nightclub so important to him . . . that he chose to bring these pictures halfway across the world [to Vietnam], when he brought so few other things with him? Was it some kind of last message?” No photos of Turpin’s own family were in the packet of his personal belongings.

“He used to tell everybody he was in importing and exporting,” Doris said, but adds, “I think dad had something to do with the CIA because he always seemed to know everything before it happened.”

Doris and Jocelyn are not blaming the CIA but believe any work Turpin might have done for the agency could have contributed to his death.

The Mike-Did-Not-Die Theory

This theory also places Turpin in a life-threatening situation, but instead of being killed he disappears to save his life or escape other problems.

About 20 years ago, this cryptic posting appeared on a now-obsolete AFVN discussion group: “Joe Ciokon was the daily War News Editor and the 6 PM TV news anchor for the American Forces Vietnam Network . . . he relieved an Army sergeant named Mike Turpin … strictly a ‘soldier of fortune’ who only came out for wars and conflicts [and] had a penthouse apartment at the International Hotel (he was probably a spook) and R&R’d in Tokyo a lot.”

Although there is nothing definitive establishing Mike as a mercenary or a spy, his extravagant lifestyle caught the eye of AFVN colleagues—and perhaps others who wanted something from him.

Turpin had good reason to vanish, Jocelyn said. “A lot of people were looking for him, everything from ex-wives to family friction.” In this theory, she continued, “he picked the perfect place knowing they had no autopsy facilities for civilians in Saigon. It would have taken nothing to pay off the landlord at that hotel, find a body . . . in the middle of the [communists’ spring 1972] Easter Offensive . . . and just say it was him. He wanted to disappear. He would have known how to do that.”

Doris is conflicted: “Half of me says yes, if he passed away, there was foul play. The other half of me says I don’t even know if he passed away at that point. So I don’t know.”

AFVN Memories

Some of Turpin’s best days in Vietnam were at AFVN as a valued television anchorman. Doris and her mother would sit in front of the TV in their sixth-floor apartment downtown and watch Turpin read AFVN’s evening news.

On one occasion Doris, about 6 years old, tagged along to observe a newscast from the control room. “I remember all the guys being really, really nice,” she said. Doris even joined her stepfather for a story that required a helicopter flight.

On May 3, 1968, Turpin was reading the 1 p.m. radio newscast when a terrorist bomb exploded in the compound that AFVN shared with Vietnamese TV. Army Spc. 5 Bob Casey, who was running the control board, described the attack at afrtsarchive.blogspot.com: “We were about a minute in when the bomb went off. I never shut the mic off and on the tape, you can hear the explosion, the falling ceilings, fluorescent lights falling and glass breaking.” There were numerous casualties but only a couple of minor injuries at AFVN. The audio recording is on YouTube, titled “The Story of AFVN Radio and TV.”

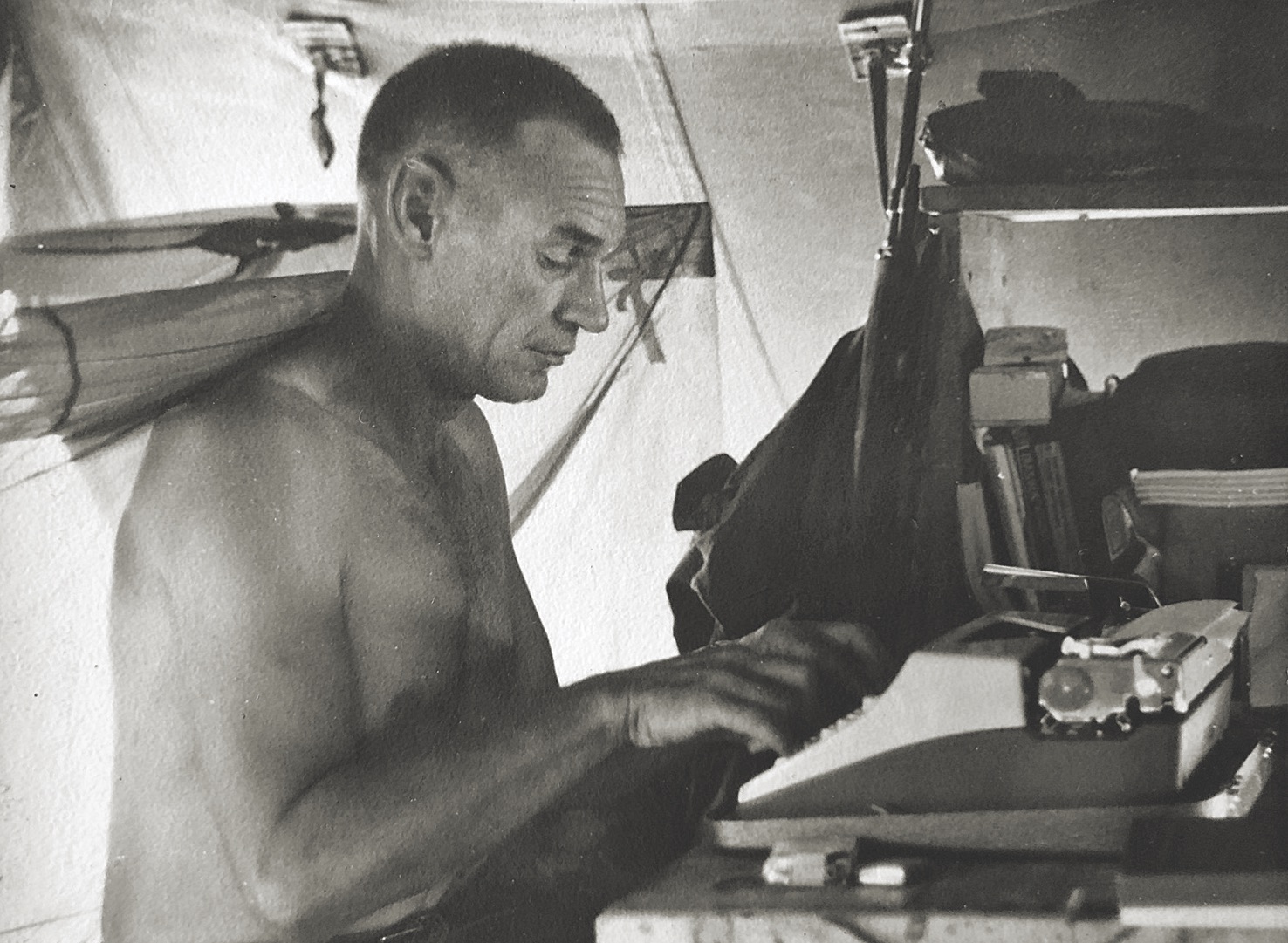

Turpin was a dedicated writer, even taking a portable typewriter into the field. “He also contributed to a story for Alfred Hitchcock [who hosted a television show that focused on mysteries],” Doris said. “I remember watching it on AFVN with dad, and the credits came up and there was his name.”

As terrorist bombings became more frequent downtown, Lily was growing more frightened. The family moved into the spacious home outside Saigon. It was not only ideal for large gatherings and formal dinners but also a welcome place for privacy.

As Doris recalled, “Dad used to come home every night from work. He would make himself an Old Forester bourbon on the rocks, sit on the porch and start reading. He read three or four books at a time.”

Her stepfather’s favorite song was “Those Were the Days,” recorded by Mary Hopkin in 1968. “Dad would hold a glass of Old Forester and sing,” she said. “I remember him playing ‘Those Were the Days’ and singing at the top of his voice. He used to just wail it.”

Doris said her stepdad had a great sense of humor and was always patient. “I never heard the man raise his voice.”

But there were skeletons in Turpin’s closet, Jocelyn discovered.

During the first of his Army enlistments, Turpin lied about his age—he was just 17—and signed up using a fictitious name. For some reason, he walked away from boot camp. He was court-martialed for desertion, sentenced to two years and released with a dishonorable discharge.

“The grief and shame from this situation almost killed his mom and dad,” Jocelyn believes. She adds that her father “spent the rest of his life trying to make up for that big mistake.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Turpin talked the Army into giving him a second chance, she said. When he went AWOL he was young, homesick and had fled boot camp, not the battlefield. He re-enlisted, again and again, then left the service with a chest-full of medals for valor.

“For those that loved and respected my dad, but were confused by some of his choices,” Jocelyn said, that dark episode in his life “explains so much. Without knowing this, any real understanding of who he truly was is incomplete.”

Turpin’s behavior might even be a model for redemption, she believes. “If it helps even one more person to understand and forgive him—or maybe inspires them to get over a rough patch in their own life and overcome their past mistakes—I feel good about it.”

Like families of troops missing in action and still waiting for news of their loved ones, Turpin’s children crave closure. “I have lived with this forever,” Doris said. “When I was younger it used to creep me out. When I got older I started to understand things better.”

Weighing the various theories of his father’s death, Matt said: “Whether it’s the bar fight or he died of some quasi natural causes or it’s something nefarious, it’s possible. I’m less inclined to think about a government cover-up.”

Jocelyn quotes her mother: “Mom said she thought he was doing something for the government and doing something important, and somebody killed him.”

There is common family agreement on this much: Turpin was a decent man, a courageous soldier and a talented journalist. Doris raves, “I absolutely adored the man, tall and lean, baby blue eyes. He taught me to be myself and to like myself. He was amazing.” V

Rick Fredericksen served as a Marine newsman at American Forces Vietnam Network 1969-70. This article is adapted from his forthcoming book with co-author Marc Yablonka, Hot Mics and TV Lights: The True Story of the American Forces Vietnam Network.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.