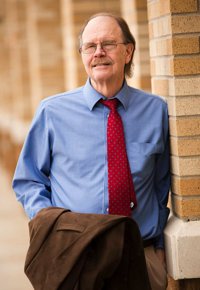

Charles R. Carr

Sergeant, 2-47 Infantry, 9th Infantry Division

May 1969-April 1970

We were drifting in and out of conversations about a world now 24 hours behind us, when the last part of the pilot’s announcement riveted our attention: “Due to vectors of artillery fire, we will be altering course for arrival in Saigon.” Any remaining hope that something would somehow rescue me was fading away. No sudden peace treaty. No last-minute assignment elsewhere.

From the division base camp at Dong Tam, I was bound for 2-47 Inf. (Mech.), 9th ID, at Binh Phuoc. “You’ll be riding ponies,” the driver had said matter of factly. I made sure everyone knew about my secondary MOS, clerk-typist; my primary specialty was infantry. Assigned to 2nd Platoon, I would be riding 1st Squad’s armored personnel carrier, Two One Pony.

At the motor pool, I had my first look at Two One Pony. Outside, mud and dust caked everything. Inside, rations, Coke and beer shared space with ammunition. “It’s home,” the track driver said. “We have no barracks, no hooch, no bunker.” Until I was able to obtain a cot, it was best, I was told, to sleep on top of the track. I would be off the ground and away from the rats.

The guys in the squad began asking me polite questions. I gave them the limited information they wanted: I grew up in Colorado. I was drafted out of grad school. I’d had two years of ROTC and genuinely hated every minute of it. Reluctantly, I told them I had been a philosophy major. Then the guys began to fill me in: number of days out…overnights back at base to let feet dry out…humping the paddies…and finally, how nobody had been killed in the squad since February, when a brand-new guy was killed on patrol. They couldn’t remember his name.

We moved out in the morning and our platoon leader, Two Six, spoke to me over the roar of the engine and clacking of treads. “The object, Carr, is to leave this place the same way you came. Nothing more than that.” I nodded and thought to myself I had found the right platoon.

I adjusted to the physical rhythms of war. In June, I had my first helicopter assault into a hot LZ somewhere in the Plain of Reeds, a swampy area to our west. Nearing the battle, I repeated the mantra, “Jump, run, form a perimeter,” praying it would keep me from screwing up. I jumped, but my pack propelled me forward and my face slammed into the dirt. I got up, sprinted 15 feet, hit the ground and stared into the distance in front of me.

I adjusted to the physical rhythms of war. In June, I had my first helicopter assault into a hot LZ somewhere in the Plain of Reeds, a swampy area to our west. Nearing the battle, I repeated the mantra, “Jump, run, form a perimeter,” praying it would keep me from screwing up. I jumped, but my pack propelled me forward and my face slammed into the dirt. I got up, sprinted 15 feet, hit the ground and stared into the distance in front of me.

Then I heard, “Back here!” I looked behind me. I had run the wrong way; the rest of our company was 30 or 40 feet away, facing the other direction.

“Come on,” the sergeant motioned. I crouched and ran to a worn-out dike that protected us from the enemy in a wood line 50 feet away. When airstrikes were ordered in, we moved back and opened fire into the bunkered positions. Bombs and napalm exploded against the enemy.

Then came the command: We were going back into the wood line, and 2nd Platoon would lead. We moved into the destroyed landscape, and I was straining to interpret it when suddenly we were pulled out. We’d never find out why, but six weeks earlier, Sen. Edward Kennedy had gone after the Army for sending the 101st Airborne Division against bunkered positions at Hamburger Hill. Seventy Americans were killed, 372 were wounded—and soon after taking the hill, they left it.

Back in the company area, the first sergeant and others from the rear shook our hands. We killed 24 enemy soldiers, we were told. We lost five. The next day, they grilled steaks for us.

In September I got a clerk job in battalion HQ and wrote narratives for medal awards, before being assigned to casualties and morning reports. I was promoted to sergeant in April, when we learned that everyone in the battalion whose DEROS was April or May would be going home early. I was glad, but clearly something was up. A communications specialist walked by one day and whispered, “It’s Cambodia.” The Army did not want extra complications from soldiers departing during what was going to be one large operation.

My last day, I threw my duffel bag in the back of the same mail truck that first brought me to Binh Phuoc. With 200 others at the Binh Hoa airport awaiting our ride home on April 22, 1970, I settled into some bleachers in the shade just off the flight lines. A plane taxied toward us, and soon applause and cheers moved across the bleachers as weary soldiers stood to acknowledge the moment. We were here and we had survived.

Charles Carr, a philosophy professor, is the author of Two One Pony: An American Soldier’s Year in Vietnam.