The Civil War contracting scandal that took down a U.S. senator—and led to the passage of “Lincoln’s Law.”

IN OCTOBER 1861 CASPER D. SCHUBARTH MADE HIS WAY FROM HIS HOME IN PROVIDENCE, Rhode Island, to the nation’s capital. The 32-year-old Norwegian immigrant brought with him a rifle, ammunition, and a letter of introduction to U.S. Senator James F. Simmons, one of his home-state lawmakers. Those three items, he hoped, would help him make a fortune.

The Civil War had begun just four months earlier, and the Department of War was hastily trying to equip the 500,000-man army that President Abraham Lincoln had persuaded Congress to authorize that summer. The war effort was already straining the industrial capacity of the Northern states. Just finding enough fabric to sew uniforms for Union soldiers was a challenge. And then there was the matter of weapons. The Union’s arsenal—filled largely with antiquated, obsolete weapons—had just 50,000 up-to-date rifles. What’s more, the government’s single armory, in Springfield, Massachusetts, could produce only about 10,000 rifles a year. If the Confederacy was to be defeated, the Union needed a lot of guns, and it needed them in a hurry.

Schubarth was eager to supply some of them. He had arrived in the United States 11 years before and settled in Providence, where in the late 1850s he opened a two-room gun shop in a neighborhood near the banks of the Providence River. His trade was strictly small time, such as making and fixing guns for local hunters.

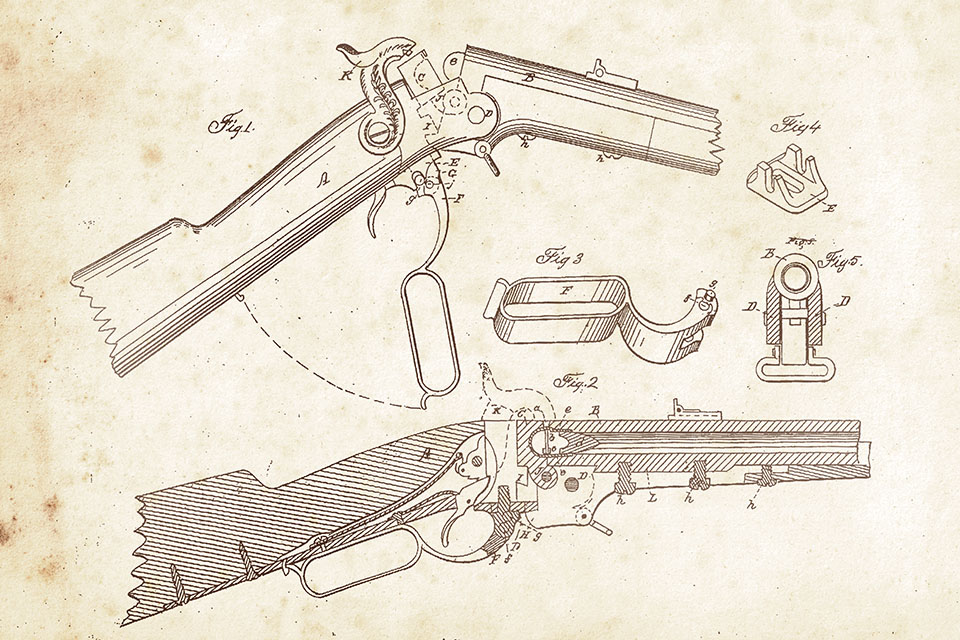

But Schubarth had big dreams. In his spare time, he had invented what his July 1861 patent application described as “a new and useful improvement in breechloading fire-arms.” A lever on the underside of the stock retracted a key, which allowed the stock to fall away from the barrel. A cartridge could then be inserted and the weapon snapped back together. Schubarth believed his mechanism, which had no sliding or rubbing joint to wear out and was designed to avoid malfunctions that plagued muzzle-loading muskets, represented a significant advance. “The above arm is effective and sure, and not liable to explode by accident, and capable of very rapid firing,” he wrote. “Its construction is simple and economical, and it is durable and not liable to repair.” He had also developed an unusual, bulb-shaped pinfire .58 cartridge for his rifle, which his patent application noted was designed to be waterproof.

Already, Schubarth’s innovations had impressed Scientific American. “Among all the breech-loading guns that we have examined, we have seen none that impressed us more favorably than Schubarth’s,” its reviewer wrote in August 1861, noting that his rifle could propel a bullet “through 15 one-inch boards at a distance of one hundred yards.” Schubarth hoped that officials of the War Department would be similarly impressed and award him a lucrative contract. He’d already lined up two well-to-do Providence industrialists, Amos D. and James Y. Smith, to finance the manufacturing operation he hoped to set up. The Smiths, the offspring of a Connecticut sea captain, had moved to Rhode Island in 1826, where they started in the timber trade but branched out into the grocery business and eventually into textile manufacturing. James Smith was also active in local politics, serving as mayor of Providence from 1855 to 1857 and becoming governor of Rhode Island in 1863.

Although Schubarth was relatively new to America, he was a quick study of American ways. As he would later testify to a government commission, the Smiths had told him that if he was going to do business in Washington, he needed to grease the wheels of government. “I heard that it was generally understood that a commission was paid for obtaining contracts,” he explained. Helpfully, the Smith firm wrote Schubarth a letter of introduction to James F. Simmons, a Republican senator from Rhode Island, explaining that Schubarth was an inventor who hoped to sell his breech-loading rifle to the army or navy.

Simmons, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Patents and the Patent Office and a former chairman of the Committee on Manufactures, was a powerful figure in Washington. Nevertheless, he met with Schubarth, a constituent, and agreed to try to help him get a government contract. In return, Simmons expected a cut of the proceeds. Neither of them probably thought anything of it. That was the way the system worked, or so it seemed. They had no way of knowing that it was a deal that would go disastrously awry.

THE CIVIL WAR WAS A STRUGGLE TO DECIDE WHETHER THE NATION WOULD CONTINUE TO EXIST and whether some Americans would be liberated from subjugation and granted freedom. But some also saw it as an opportunity to make a lot of money. “Greed on the home front became an inglorious but oft-repeated counterpoise to the sacrifice of the troops at the front,” Stuart D. Brandes wrote in his 1997 book, Warhogs: A History of War Profits in America.

That corruption was enabled by the Union’s lack of preparedness for such a conflict and by the misjudgment that the rebellion would be crushed easily in a few months. Just a month after hostilities began, Lieutenant Colonel James W. Ripley, the head of the Bureau of Ordnance, sold off 5,000 carbines at a bargain price, thinking they wouldn’t be needed. He also refused to buy new breech-loading and repeating rifles. His resistance to change, in fact, earned him the nickname “Ripley Van Winkle.”

But even Ripley eventually realized that the Union desperately needed rifles. The War Department wanted to equip Union forces with the Springfield Armory’s .58-caliber Model 1861 rifle musket, a design that military historians Earl J. Coates and James L. Kochan have called “the zenith of the development of muzzle-loading military weapons.” When Springfield couldn’t produce enough of them, Ripley began looking for private suppliers. According to Brandes, Ripley decided to stimulate production by paying a “liberal profit,” giving manufacturers $20 for rifles that he calculated they could make for less than $14. Ripley hoped such incentives would not only attract existing gun manufacturers but also encourage other companies to start making weapons.

According to Coates and Kochan, most of the companies that answered the call weren’t even in the gun business to begin with. One example was Alfred Jenks and Sons, a Pennsylvania-based manufacturer of textile machinery. Ripley signed contracts with the firm for 50,000 rifles at a time, to be delivered by early 1862. Surely Ripley knew these contracts were unrealistic, but perhaps he hoped that at least a few of the contractors would somehow come through. Ripley was even willing to make deals with entrepreneurs who didn’t have factories of any sort. One of them, thanks to Senator Simmons’s advocacy, was Casper Schubarth.

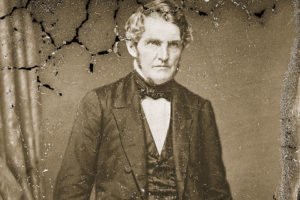

JAMES F. SIMMONS WAS BORN IN 1795 IN LITTLE COMPTON, RHODE ISLAND, where he grew up working on a farm and had limited education. As a young man, he had tried to make his fortune in manufacturing. He also got involved in politics, and in 1827 Simmons was elected to the state General Assembly, where he served until his fellow legislators sent him to represent Rhode Island in the U.S. Senate in 1841 as a Whig. When they balked at giving him a second term, he came back home and applied himself to business, in particular producing yarn. Political historian Heather Cox Richardson has described him as “a very wealthy—and somewhat shady—cotton trader.” Eventually, in 1857, his former colleagues in the state legislature again sent him to the U.S. Senate, this time as a Republican.

But even as a politician, Simmons thought like a businessman. He was a strict protectionist who wanted to use tariffs to keep imports from challenging domestic manufacturers. The New York Times would later note that in Senate debates, Simmons was a font of financial and commercial statistics, often rendering him the victor against opponents “who did not agree with his deductions, but could not answer his array of figures.”

Simmons was also keen on making a profit from politics. As Schubarth would later tell a government commission, Simmons had repeatedly mentioned commissions he expected to receive in exchange for steering government business to the right people. Schubarth said Simmons told him, “I shall be a rich man when I get that commission,” or words to that effect.

Simmons may also have expected bribes because he knew he could deliver. In Schubarth’s case, he quickly arranged a meeting with Ripley, who had been promoted to brigadier general, and other War Department officials. Schubarth’s main goal was to get a contract to make 10,000 breech-loading rifles from his design. He figured $35 for the standard model and $37.50 for a larger version that would include a bayonet.

Ripley, however, wasn’t interested in Schubarth’s invention. “I was told there was no time for trials,” Schubarth later recalled. As Ripley later explained in a message to another official, “the party bringing it was told that it was not considered a suitable arm for military service, and that we did not want to contract for it.” For that matter, Ripley wrote, he wasn’t even interested in giving Schubarth a contract to make Springfield-style muskets, as he figured he already had enough contractors on the case.

Schubarth undoubtedly left the meeting dejected. But perhaps through Simmons’s intervention, Ripley abruptly changed his mind. Two days after the meeting, he wrote to Schubarth, offering him a contract to make 20,000 Springfield-style muzzle-loading muskets, with parts that would be interchangeable with others of that design. The government wanted at least 1,000 of the rifles delivered in January 1862 in boxes of 20, with similar quantities in February and March. After that, Schubarth was to produce at least 2,500 rifles a month until the entire order was filled and arrange for a federal inspector to certify that each weapon was in working order before delivery. On receipt of those certificates, the government would pay Schubarth $20 per musket. Schubarth quickly agreed to the deal.

But there was another clause that wasn’t written into the contract. Orally, Schubarth agreed to pay a kickback of 5 percent—$1 per musket—to Simmons for pulling the strings necessary to get the deal. Schubarth later testified that he didn’t know that paying such a bribe was wrong. “I understood, on the contrary, that it was customary to make compensation for such services, and I have heard of many cases in which it was said to have been done,” he said. Schubarth added that he’d heard of a case in which a manufacturer paid a politician $2 for every pistol that the government purchased. As Schubarth would later recall, Simmons continually talked to him about pieces that he had of various deals, saying things such as “I shall be a rich man when I get that commission.”

As lucrative as Schubarth’s deal might have seemed, the Smiths, Schubarth’s initial backers in Providence, wouldn’t go for it. The order of 20,000 muskets wasn’t enough to pay back the investment required to make the arms in the time specified, they told him. So, as Schubarth later testified, Simmons arranged another meeting at the War Department, where the two of them explained the predicament to Ripley.

On November 26, Ripley again wrote to Schubarth, adding 30,000 muskets to the order, for a total of 50,000. He also relaxed Schubarth’s deadlines: He had until May 1862 to deliver his first 1,000 muskets, and he didn’t have to scale production up to 2,000 a month until September.

FOR AN ENTREPRENEUR OF MODEST MEANS, THE MILLION-DOLLAR WAR DEPARTMENT CONTRACT must have seemed like an incredible stroke of good fortune, even with the 5 percent cut to his political wheel-greaser. But there was a catch. He actually had to manufacture 50,000 rifles. Although he’d been making firearms since 1845, he’d never done it “upon the large scale contemplated in this contract,” as he later admitted. He didn’t have a factory and had no time to build one.

To make up for that, Schubarth came up with a plan. He would subcontract—“branch it out,” as he put it—the production of the parts to an array of other companies in several states. The barrels would be made by the Trenton Iron Works and finished by other Trenton-based firms, Field and Horton, and Ashton. The mountings would be made by two Connecticut-based companies, Pecksmith Manufacturing and Bigelow. The stocks would come from Empire Works on East 24th Street in New York City. The idea was that he would have all those parts delivered to his shop in Providence, where he would assemble the rifles and stamp his name on the finished product.

By then, the Smiths, his original backers, had stepped away from the musket deal—“They thought the terms were too stringent,” as Schubarth later recalled. So as he set up his supply chain, Schubarth also acquired two new backers, Frederick Griffing of Brooklyn, New York, and James M. Ryder, of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. On February 15, 1862, they signed an agreement that gave Griffing and Ryder each a third of the profits.

Schubarth informed Griffing and Ryder about his secret arrangement with Simmons, and at this point, the story gets a little murky. The two new partners, as Simmons later put it, “wanted to have an understanding with me about my commissions,” so Simmons met with the two men. “I saw them” Simmons said, “and took from them an agreement in writing [that they would] pay at certain stipulated times (I think in about a year from this time) the amount agreed upon.” The backers gave Simmons a note payable in August 1862 and another payable in September, amounting to $10,000—considerably less than the $50,000 he’d originally expected to receive. As Schubarth later surmised, Simmons probably assumed that producing the arms was turning out to be so expensive that he had to take a discount in his bribe.

Schubarth apparently wasn’t part of the dickering. “I consider myself honor-bound to give Senator Simmons five percent commission on both orders,” he later testified, “and I think he considers me bound to keep my promise.”

THE WEB OF CORRUPTION THAT ENVELOPED THE UNION’S MILITARY PROCUREMENT soon began to unravel. In January 1862, Lincoln replaced Secretary of War Simon Cameron with former attorney general Edwin Stanton. Stanton promptly began cleaning up the corruption and improving efficiency. According to historian Brandes, Stanton took an especially hard look at the government’s 36 outstanding contracts for 1,164,000 Model 1861 muskets. At the time, that number was more than twice as many as the Union army estimated it would need, and to many it seemed like a glaring example of waste and shady dealings. At the behest of the U.S. Senate, Stanton appointed a two-man Commission on Ordnance Contracts, with former war secretary Joseph Holt and social reformer Robert Dale Owen as its members. They began going through the deals Ripley had made, looking for ones that could be cut back or canceled.

Schubarth’s contract soon came under scrutiny. The factories making musket parts for him were lagging in production, and he was struggling to keep to the schedule the government had set. In February 1862, in a letter to the War Department, he hinted at the problems, even as he insisted that he was still on pace. “I have 5,000 muskets that in all probability will be ready a month before the specified time of the order, plus another 45,000 stocks being made…and the same number of barrels,” he wrote. “All the parts of the muskets, except the bayonets and guards, which will receive my special attention, are in a satisfactory state of forwardness, and will, without doubt, be ready so I can fulfil [sic] my order to the government within the time specified.”

In mid-April, just weeks before he was supposed to start delivering muskets, Schubarth asked Stanton for more time. The gunsmith said that he was ready to deliver the first 1,000 muskets “except the barrels, which various causes have delayed from time to time. I am doing the best I can, and shall require a little indulgence in getting them ready.”

A few weeks later, the Commission on Ordnance Contracts summoned Schubarth to Washington to appear at a June 2 hearing. The commission had also learned—it’s not clear exactly how—of Simmons’s role in obtaining the contract, and he was called to testify as well.

At the hearing, Schubarth blamed the delays on his subcontractors, who he said had sent him shoddy parts at the start. “The barrels at first received were not good, but lately, they are getting better,” he testified. “The borer found but three in one hundred defective, and they look as if they would finish well.”

But the commission seemed more interested in how Simmons had helped Schubarth get the contract. When the senator testified, he readily acknowledged that Schubarth’s partners had given him the two promissory notes, and said that he fully expected to be paid the $20,000. “He did not doubt the propriety or legality of receiving a commission for his trouble,” the commission’s report noted.

Schubarth, though, went even further. He told the commission that he felt that he still owed his fixer the full $50,000 he originally had promised. “I mean to state my impression that Mr. Sen. Simmons expects me to keep the promise I made to him to pay him five percent, for procuring the orders for me upon the number of arms included in both orders, is derived from various conversations with him, the details of which I do not particularly remember,” he testified.

It might seem surprising that both the bribe-payer and a corrupt official would be so candid about a corrupt deal. But as the commission noted in its June 17, 1862, report, what they had done wasn’t actually illegal at the time. An 1808 statute barred members of Congress from taking part in a government contract, but that law didn’t appear to apply to Simmons, since his agreements had been with Schubarth and his backers, not with the War Department.

As for Schubarth, the commission decided that he was guilty of nothing more than naiveté. “We are satisfied that Mr. Schubarth is personally innocent of any illegal or immoral purpose, and of all consciousness of violating the policy of the government,” the commission said. “He is a foreigner, not very intimate, it may be assumed, with our institutions, and in offering compensation to Sen. Simmons, he only did what he was assured by intelligent businessmen (Americans by birth) was customary.” If anyone was to blame, it was “a vicious system of administration, which in abandoning the law, forces the citizen to seek the patronage of his government by purchase through mercenary agencies, instead of obtaining it by open and honorable competition.”

Instead, the commission and Ripley decided that Schubarth would be allowed to continue making arms for the government, but that the order would be reduced from 50,000 to 30,000 muskets, deducting the number that Schubarth had failed to produce as scheduled. The new contract contained a clause specifying that no member of Congress, army officer, or agent of the U.S. military could share in or benefit from any part of the deal.

SIMMONS, DESPITE HIS CANDOR ABOUT THE KICKBACK AGREEMENT Simmons, despite his candor about the kickback agreement, wouldn’t get off as easily. He had embarrassed Congress: One of its own was a war profiteer, and an unapologetic one at that.

On June 18, 1862, the day after the commission issued its damning report, Senator Lazarus Powell, a Union Democrat from Kentucky, introduced legislation to bar members of Congress from accepting fees for obtaining government contracts. As John Thomas Noonan recounts in his 1987 book, Bribes, the Senate Judiciary Committee amended the bill to ban fees for obtaining government jobs as well. The bill was sent to the Senate floor, where it was passed with little debate and without a roll call vote.

It similarly slipped quietly through the House of Representatives. One Congressman, an elderly Union Whig from Kentucky named James Wickliffe, wondered if it would become illegal to accept “presents” such as a carriage and horses from a contractor. The chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, John Bingham of Ohio, assured him that it would. Again, the bill was passed by acclamation, and went to President Lincoln, who signed it into law on July 16. Going forward, a member of Congress who accepted a bribe risked up to two years in prison and a fine of up to $10,000, and Lincoln now had the power to void the contract as well, if he so chose.

On July 2, 1862, Senator Joseph A. Wright of Indiana, a Republican who had formerly been a Democrat, submitted a resolution accusing Simmons of misusing his influence to obtain the musket contracts and calling for his expulsion from the Senate. On July 8 the matter was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee, which called Schubarth and Simmons to testify.

Schubarth told the same story as before, the details of which were corroborated by Simmons. In his defense, Simmons insisted—somewhat bizarrely—that his efforts to influence government contracts were motivated by patriotism, not greed. He claimed that he’d arranged the deals out of concern that the Union didn’t have enough rifles for its draftees and that he figured he could help by lining up reputable manufacturers who could quickly furnish the needed weapons. Duty to country aside, though, he indicated that he still expected to get his cut.

The members of the Judiciary Committee were a bit perplexed. In their July 14 report, they acknowledged that Simmons had a distinguished career as a public official, but they judged his actions to be inexcusable—especially with the Civil War raging and the public treasury subjected to “untold and frightful drains.” By then, Congress had passed a new law that made it illegal for members of Congress to accept anything of value in exchange for procuring a contract. The problem was that Simmons’s corrupt acts had taken place before the law took effect. So the committee punted the matter back to the full U.S. Senate, only recommending that it take whatever action seemed appropriate.

But Simmons apparently sensed that the game was over. Rather than risk the indignity of being formally expelled by his peers, on September 5, 1862, he resigned from office. It was the first time in U.S. history that a senator had quit under a cloud of corruption. He went back to his manufacturing businesses in Rhode Island, where he died two years later. His obituary in the New York Times tactfully made no mention of his bribe taking. According to historian William B. Edwards, it’s unclear whether Simmons ever actually got any money from Schubarth.

The Simmons case helped pull away the curtains from the massive corruption that plagued the Union cause. Lincoln was outraged by such graft. “Worse than traitors in arms are the men who pretend loyalty to the flag, feast and fatten on the misfortunes of the nation, while patriotic blood is crimsoning the plains of the South, and their countrymen are moldering in the dust,” he inveighed.

BUT IT WAS JUST THE START. ACCORDING TO HISTORIAN BRANDES, the following year, after unscrupulous businessmen tried to exploit Union shortages of supplies by jacking up prices, Congress considered applying martial law to defense contractors, and possibly even making defense fraud a capital crime.

Instead, at Lincoln’s behest, Congress in March 1863 passed the False Claims Act. The new statute had a novel twist. In addition to providing criminal penalties for defense fraud, it allowed whistle-blowers to bring suits against corrupt military suppliers and enabled them to collect a portion of the amount that the government recovered in the case. The first contractor convicted under the statute, a Philadelphia businessman, received a five-year sentence for selling adulterated coffee to the Union army. In the years that followed, “Lincoln’s Law,” as it still is known, would become one of the government’s most potent tools for exposing those who sought to cheat the military and taxpayers.

Schubarth escaped punishment, but he was never able to complete his government contract. According to military firearms historian George D. Moller, he only managed to deliver 500 rifles in 1862 and 9,000 in 1863, a fraction of the order. Only the first 500 had Schubarth’s name stamped on them, which has led some to speculate that he even had to subcontract the final assembly to another company. When his contract expired in 1863 before it could be fulfilled, he wrote to Ripley and tried to obtain another deal, but the government declined to give him one.

His dreams of becoming a big-time arms seller dashed, Schubarth went back to making fowling guns for hunters in Providence, and for a time dabbled in making surgical instruments as well, before finally turning over his shop in 1866 to his brother Carl, according to firearms historian William O. Achtermier. Schubarth moved to Brooklyn, where he got into the iron and steel business. In 1868, he and nine other investors started the Port Oram Iron Company in New Jersey, which built a blast furnace that produced 150,000 tons a year. In 1875 he was among the partners who owned the rights to patents for a composite steel and wrought-iron girder invented by Brooklyn inventor Charles P. Haughian, as well as a second patent for burglarproof window grates. By 1890 he had moved to Newark, where city directories variously listed him a “foreman” and a “steel dealer.” He apparently became prosperous enough to establish his family in polite society, and his daughter Clara married a local furniture magnate. His last years were spent in a three-story house on a tree-lined Newark street, where he died in 1908.

Schubarth’s name is kept alive mostly by the inscriptions on the handful of surviving muskets that he produced for the Union army, which today sell for several thousand dollars apiece, and for the similarly rare specimens of ammunition for the breech-loading gun that he had hoped to manufacture for the military. All the same, it can be argued that the obscure Norwegian immigrant made a significant contribution to the Union cause. His misadventure brought down a corrupt senator and, along with other such cases, paved the way for laws and oversight that made the procurement process more honest and efficient. That, in turn, helped make it possible for the North’s industrial might to overwhelm the Confederacy’s resources and supply the mighty force that preserved the nation. MHQ

PATRICK J. KIGER is an award-winning journalist who has written for GQ, the Los Angeles Times Magazine, Mother Jones, Urban Land, and other publications.

[hr]

This article appears in the Spring 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Musketgate

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!