Since the earliest days of the Republic, Benedict Arnold has been the American phrase for traitor. Other villains from Aaron Burr to Aldrich Ames have come and gone through the course of American history, but none have quite matched Arnold’s nefarious reputation. Willard Sterne Randall, however, notes that Benedict Arnold did not plot treachery alone. Instead, the general’s wife, Peggy Shippen Arnold, carried the key to her husband’s betrayal. With today’s concern for gender equality, perhaps it is time to remember a woman as America’s greatest traitor.

NEARLY ALL HER LIFE, PEGGY SHIPPEN WAS SURROUNDED BY THE TURMOIL of an age of wars and revolution. She was born with the British Empire in 1760, only weeks before the French surrendered all of Canada. Before her third birthday, British America had grown by conquest from a strip of coastal colonies to nearly half of North America. The town of Philadelphia, where her father, Judge Edward Shippen, held a lucrative array of colonial offices, was the largest seaport in America. A center for trade and its regulation, it was a natural target for protests when resistance to British revenue measures flared in the 1760s. By the age of five, she had seen riots in the streets outside her father’s handsome brick town house.

The revolutionary movement grew all her childhood. At 15 she listened at her parents’ dinner table as their guests argued politics: George Washington, John Adams, Silas Deane, and Benedict Arnold were among the patriots who dined at the Shippens’; British officials and officers included General Thomas Gage and the intriguing John Andre. By the time Peggy was 17, the British army occupied Philadelphia and she was being linked romantically with the young British spymaster. After the Americans reoccupied the city, and before she was 19, Peggy married Military Governor Benedict Arnold and helped him to plot the boldest treason in American history–not only the surrender of West Point and its 3,000 men but the capture of Washington, Lafayette, and their combined staffs.

Delicately beautiful, brilliant, witty, a consummate actress and astute businesswoman, Peggy Shippen was, new research reveals, the highest paid spy of the American Revolution. Understandably, the Shippen family destroyed papers that could connect her to the treason of Benedict Arnold. As a result, for two centuries she has been considered Arnold’s hapless and passive spouse, innocent though neurotic. But new evidence reveals that she actively engaged in the Arnold conspiracy at every step. She was a deeply committed Loyalist who helped persuade her husband to change sides. When he wavered in his resolve to defect, it was she who kept the plot alive and then shielded him, risking her life over and over. Ultimately expelled from the United States, she was handsomely rewarded by the British “for services rendered.”

When Margaret Shippen was born, on June 11, 1760, her father, who already had a son and three daughters, wrote his father that his wife “this morning made me a present of a fine baby which, though the worst sex, is yet entirely welcome.” Judge Shippen was usually cheerful about his large brood: The Shippens were one of colonial America’s wealthiest and most illustrious families.

The first American Shippen–Peggy’s great-great-grandfather, the first Edward–had immigrated to Boston in 1668 with a fortune from trade in the Middle East. He and his wife were granted sanctuary in Rhode Island by Governor Benedict Arnold, the traitor’s great-grandfather. The couple resettled in Philadelphia on a two-mile-deep riverfront estate. Shippen later became Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly and the second mayor of Philadelphia.

Peggy’s father, the fourth Edward in the line, was a conservative man who seemed constantly worried, usually about money or property. He followed his father’s wishes and practiced law, also holding several remunerative colonial offices simultaneously–admiralty judge, prothonotary, recorder of deeds–and was at first firmly on the British side in the long struggle that evolved into the Revolution. His tortured reactions to the almost constant tensions that accompanied years of riots, boycotts, and congresses in Philadelphia were the backdrop for his daughter Peggy’s unusual childhood.

When Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, before Peggy’s fifth birthday, her father read aloud about “great riots and disturbances” in Boston. He considered the act oppressive, but he opposed illegally destroying stamped paper. “What will be the consequences of such a step, I tremble to think….Poor America! It has seen its best days.” By the time Peggy was eight and learning to read leather-bound books in their library, her father’s admiralty court had become the center of the storm over British taxation. When she was 10, his judgeship was abolished.

As the colonial crisis dragged on, Shippen lectured his favorite daughter on disobedience: Bad laws had to be repealed; simply to ignore or resist them would open the door to anarchy. Despite his drawing-room bravery, however, Shippen refused to take a public stand, careful to avoid offending radicals or street mobs that might attack his property or harm his daughters. He burst into a rare fit of rage at Thomas Paine’s “book called Common Sense, in favor of total separation from England….It is artfully wrote, yet might be easily refuted….This idea of independence, though sometime ago abhorred, may possibly, by degrees, become so familiar as to be cherished.”

Judge Shippen’s only son, the fifth Edward (“Neddy”), had early shown himself to be inept at business, and he eventually squandered much of the family fortune. The judge decided to educate Peggy as if she were his son. Peggy curled up in a wingback across from her father to read Addison, Steele, Pope, Defoe, all the latest British writers. Her mother saw to it that she was instructed in needlework, cooking, drawing, dancing, and music, but in none of her surviving letters is there any of the household trivia of her time.

Peggy had a distinctive literary style and wit, and, like her father, she wrote with unusual clarity. A quiet, serious girl, she was too practical, too interested in business and in making the most of time and money, for frivolity. By age 15, as the Revolutionary War began, she was helping her father with his investments. She learned the finer points of bookkeeping, accounting, real estate and other investments, importing and trade, banking and monetary transactions-and she basked in her father’s approval.

But she had also been studying her sisters’ manners and social behavior. It was at the fortnightly dances in Freemasons Hall that young men who danced with them began to notice Peggy: She was petite, blond, dainty of face and figure, with steady, wide-set, blue-gray eyes and a full mouth, which she pursed as she listened intently.

As far into the new politics as Judge Shippen would delve was to invite partisans of all stripes to his brick mansion on Fourth Street, in Philadelphia’s Society Hill section, to air their views at his dinner table. In early September 1774, Peggy and her family entertained some of the dele gates to the First Continental Congress. Few, if any, foresaw a war of revolution against the mother country; many expected to conciliate their complaints with Parliament peacefully. Of all the colonies, Pennsylvania was the most divided: The majority was made up of pacifist Quakers and members of the more than 250 German pietist sects, and there was the strong Penn proprietary party, loyal to the British.

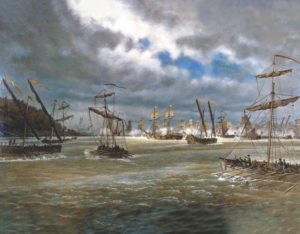

That steamy September, Philadelphians agonized over the course of the New England radicals’ confrontation with the crown in British occupied Boston as post riders, delegates, militiamen, and redcoats came and went down the broad cobbled streets, making it increasingly difficult to remain neutral. Congressional delegate Silas Deane wrote to his wife that “this city is in the utmost confusion.” Rumors of British invasion also were flying; during one panic, Pennsylvania militiamen drilled and marched past the Shippens’ town house even as the last red-coated British regiment in the middle colonies strode to the waterfront and boarded troop transports taking them north to reinforce Boston.

One young British officer who could have chosen to join them was Second Lieutenant John Andre of the 7th Foot, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, who had arrived in Philadelphia just a few days earlier. Sent out from England to join his regiment, Andre was en route to Quebec. He had been a peacetime officer for five years and had never fought in battle but instead had pursued the life of a dilettante poet, playwright, and artist.

From the safety of England, Andre had taken the unrest in America lightly, but upon arrival he found Philadelphia in the grip of anti-British frenzy. It was not a safe place for a young, solitary British officer. Oddly, he decided to travel not aboard a British warship but on foot alone north to Lake Champlain. He sailed on to Quebec in a schooner, in the company of a black woman, an Indian squaw in a blanket, “and the sailors round the stove.” It was the first of John Andre’s strange and romantic journeys through an America he would never understand.

As Andre meandered north, 33-year-old shipowner and revolutionary Benedict Arnold, who had arrived in Philadelphia with the Connecticut delegation to Congress, was accompanying his mentor, Silas Deane, to a series of political caucuses and dinners. A self-made man of means and long a leader of the radical Sons of Liberty in New Haven, Arnold was helping to plan the systematic suppression of antirevolutionary sentiment. The purpose of the Congress was to protest British oppression, but Sons of Liberty from a dozen colonies used the opportunity to discuss the elimination of Loyalist opposition.

Yet Arnold and Deane had time for dinners in Philadelphia’s best houses. And one Loyalist family, the Shippens, stood out for their hospitality. Deane and Arnold were invited to the judge’s dinner table, where Shippen introduced his daughters, including the youngest, the precocious Peggy. Although only 14, she was already one of the city’s most popular debutantes. Flirtatious and quick-witted, she could talk confidently with men about politics and trade. Benedict Arnold met her for the first time at dinner that September.

Peggy heard Benedict Arnold’s name frequently in the next few years as the Revolution turned to war and its leaders put on uniforms and fanned out to fight the British. Arnold’s attack on Fort Ticonderoga, his heroic march to Quebec and his daring assault on the walled city, his naval campaign on Lake Champlain, his wounding, and his quarrels over promotion often put his name in the Philadelphia newspapers. A few blocks from the Shippen house, a new ship in the Pennsylvania navy was given Arnold’s name, and that was in the papers, too.

News of the war often touched closer to home. Peggy’s oldest sister’s fiancee, a rebel, was missing and presumed killed in the American rout on Long Island. Her brother, Neddy, 18, on the spur of the moment decided to join the British army in Trenton for the Christmas festivities. When Washington attacked, Neddy was captured. He was freed by the Shippens’ erstwhile dinner guest, George Washington himself. All of Judge Shippen’s careful neutrality was jeopardized. Stripping the youth of any further part in family business affairs, the judge turned his son’s duties over to Peggy.

When the Americans invaded Canada late in 1775, the British made a stand at Fort St.-Jean on the Richelieu River, surrendering only after a long siege. One of the officers captured was 25-year-old Second Lieutenant Andre. Freed on parole, he was sent south with the baggage of his fellow officers to house arrest in Pennsylvania. In Philadelphia, while he attended to provisions for his fellow prisoners, Andre had time to explore “the little society of Third and Fourth Streets,” the opulent town houses of Peggy’s neighborhood. The romantic young officer was ushered into the Fourth Street home of Judge Shippen and introduced to 15-year-old Peggy Shippen. Before he left for an indefinite term in captivity on the Pennsylvania frontier, he played his flute and recited his poetry and asked to sketch her.

One year later Andre was exchanged for an American prisoner. Then, in the autumn of 1777, when Peggy was 17, General Sir William Howe’s British army drove the Americans out of Philadelphia and marched up Second Street, two blocks from the Shippens’. Andre had recently given the orders for a British regiment to fix bayonets, remove the flints from their muskets, and attack a sleepy American unit at nearby Paoli. The increasingly callous Andre tersely described the massacre in his regimental journal, calling the Americans a “herd” as nearly 200 men were killed and a great number wounded. He noted they were “stabbed…till it was thought prudent to…desist.”

As an aide at British headquarters in Philadelphia, Andre decided to follow the example of his commanders and seek diversions from the toils of killing. He and his elegant friends reconnoitered in the best society they could find, and Andre began calling on the Shippens, accompanied by his friends Captain Andrew Snape Hamond of HMS Roebuck and Lord Francis Rawdon, who considered Peggy the most beautiful woman he had ever seen. Even a conquering officer, however, could not hope to escort a Philadelphia debutante to the incessant round of military balls without a prior round of introductions. The first step was the morning visit to the drawing room of the intended partner. Andre frequently showed up, sketch pad under his arm, for obligatory cups of tea and chaperoned talks about the latest books, balls, and plays. In the evenings Andre, who was now a major, and his assistant, New York Loyalist Captain Oliver De Lancey, were hard at work turning a former warehouse on South Street into a splendid theater.

Peggy Shippen probably fell in love that winter with the charming major. But he flitted from one drawing-room beauty to another, serious about none of them. Still, he liked to be with Peggy; he liked to sketch her, showing her as elusively elegant and poutish, sometimes turning away, sometimes fixing him with an enigmatic smile. He enjoyed breakneck sleigh rides with her at his side, her friends crowding in with them under heavy bearskin rugs.

But when Peggy stepped out for the evening, it was more often on the arm of Captain Hamond, who later said, “We were all in love with her.” One of the season’s highlights was a dinner dance aboard the Roebuck. Peggy was piped on board the ship, which was illuminated with lanterns for the occasion. She sat down at Hamond’s right for a dinner served to 200 invited guests, then danced until dawn.

By late April 1778 the British learned they were to withdraw to New York City and prepare for the arrival of the French, the revolutionaries’ new ally. Philadelphia was too exposed. A new British commander was coming; General Howe was being recalled. John Andre volunteered to prepare a lavish farewell, a Meschianza, including a waterborne parade, a medieval tournament, a dress ball, and an enormous dinner party. No other effort of Andre’s ever approached this opulent festival. He designed costumes for 14 knights and their squires and “ladies selected from the foremost in youth, beauty, and fashion.” For the ladies, he created Turkish harem costumes evoking the Crusades. He designed Peggy’s entire ward robe and sketched her in it. Andre’s own glittering costume featured pink satin sashes, bows, and wide baggy pants.

Peggy’s father grumbled, but he shelled out enough gold to outfit three of his daughters. As Peggy rode home the next morning, a Quaker diarist wrote, “How insensitive do these people appear while our land is so greatly desolated.”

Before John Andre left a few weeks later, he gave Peggy a souvenir that showed how close they had become: a locket containing a ringlet of his hair. Though parted, they wrote each other secretly through the lines, at great risk to Peggy, directing the letters through a third party.

In May 1778, as the British made ready to evacuate Philadelphia, George Washington’s newly appointed military governor was preparing a peaceful takeover of the capital city. Benedict Arnold–the hero of Ticonderoga, Quebec, and Saratoga–had been shot twice through his right leg and was still unable to stand without a crutch. Washington had urged him to take more time to recover, but Arnold insisted on returning to the war, so Washington gave him the rear-area command–thus placing Arnold in the middle of a political cross fire between the Continental Army and Pennsylvania politicians. As the British sailed away, Arnold drove into the city in his coach-and-four with his liveried servants, aides, and orderlies. From their brick mansion, the Shippens could see the American light horse ride by.

Benedict Arnold’s duties as military governor included social evenings arranged by his spinster sister, Hannah, who was also rearing his three young sons; Arnold’s wife had died while he was attacking Canada. Once an impoverished orphan, Arnold now moved freely in Philadelphia’s elite society, sipping tea with the Shippens, the Robert Morrises, and other wealthy merchants and lawyers, and playing host to members of Congress at lavish dinners in his headquarters mansion.

He often encountered Peggy Shippen at these gatherings. Frequently his carriage was seen parked in front of the Shippen house, where British officers had come to call only a few months earlier, and as the summer of 1778 progressed, Peggy became known as the general’s lady. At first, resentment that the American hero of Saratoga was courting the Loyalist belle of British officers’ balls was confined to a little sniping in Congress. Arnold’s insistence on inviting Loyalist women to revolutionary social events brought increasing criticism, yet Arnold seemed oblivious as he spent more and more time with 18-year-old Peggy.

In September 1778 Arnold declared himself a serious suitor in two letters, one to Peggy, one to her father. A relative of Peggy’s wrote that “there can be no doubt the imagination of Miss Shippen was excited and her heart captivated by the oft-repeated stories of his gallant deeds, his feats of brilliant courage and traits of generosity and kindness.” Peggy seemed especially touched by his paying for the education and upbringing of the three children of his friend Dr. Joseph Warren, who had been killed at Bunker Hill. But Peggy had other reasons for falling in love with Benedict Arnold: He was still young (37), ruggedly built despite his wounded leg, animated, intelligent and witty, strongly handsome and sometimes charming. It was obvious a life with “the General,” as she always called him, would not be dull.

The judge did not say yes, but he did not say no. He wrote to his father to seek advice. But the more Arnold was publicly criticized for his leniency to Loyalists and his quite open love of one, and the longer the judge balked, the closer the two lovers drew together. Arnold had come to appreciate her “sweetness of disposition and goodness of heart, her sentiments as well as her sensibilities.” He had faced few more implacable adversaries than Judge Shippen, who worried about his daughter’s marrying an invalid. Finally, however, relatives persuaded the judge that Arnold was “a well dispositioned man, and one that will use his best endeavors to make Peggy happy.” The judge also liked the fact that Arnold settled a £7,000 country estate named Mount Pleasant on her as a wedding present.

On the other hand, the judge didn’t like what he was beginning to hear about Arnold’s private business dealings; but months of attacks on Arnold in the press by radical political opponents had made Peggy all the more determined to marry him. In the end, Judge Shippen seems to have acceded to his daughter’s engagement only when his continued refusal made Peggy, now thoroughly in love, hysterical to the point of fainting spells.

On April 8, 1779, Arnold’s nine-month siege ended. He rode down Fourth Street with his sister, his three sons, and an aide for an evening ceremony in the Shippen home. In his blue American major general’s uniform, Benedict Arnold, 38, married 18-year-old Peggy Shippen. A young relative wrote that Peggy was “lovely, a beautiful bride” as she stood at last beside her “adoring general.”

IN MAY 1779, WITHIN ONE MONTH OF THEIR WEDDING, the couple entered into a daring plot to make Arnold a British general who would lead all the Loyalist forces and bring the long war to a speedy conclusion. All through their courtship there had been a mounting furor in the press about Arnold’s alleged profiteering as military governor. No proof has ever been found that, up to then, he had done anything more than use his office to issue passes that helped Loyalist merchants, who in turn cut him in for a percentage of their profits; and once he diverted army wagons to haul contraband into Philadelphia for sale in stores. Both were common practices, but Arnold was often stiff-necked and arrogant in his dealings with Pennsylvania revolutionaries.

When Pennsylvania brought formal charges against Arnold, George Washington refused to intervene and, far from supporting him, treated him with the same cold formality he reserved for all officers facing court martial. Arnold had already endured years of censure and controversy, and Washington’s aloofness, coupled with a ferocious attack from Congress and in the newspapers, evidently drove him over the edge. Peggy seems not only to have approved of his decision to defect to the British but to have helped him at every turn in a year and a half of on-again, off-again plotting that at least once she alone managed to keep alive.

When Arnold’s prosecutors produced no evidence to convict him, and when Washington, whose generals were preoccupied, was unable to bring about a speedy court-martial to clear him, the proud hero could tolerate the public humiliation no longer. On May 5, 1779, he wrote a drastic letter to Washington: “If Your Excellency thinks me criminal, for heaven’s sake let me be immediately tried and, if found guilty, executed.”

Apparently that same day, with Peggy’s assistance, Arnold opened his secret correspondence with the British, using Peggy’s friends and Philadelphia connections. A china and furniture dealer, Joseph Stansbury, who was helping Peggy decorate the Arnold house, acted as courier through the lines to Andre at British headquarters in New York City, where Stansbury often went on buying trips. Peggy already had been sending harmless messages to Andre with Stansbury. She now worked with Arnold to encode his messages, using a cipher written in invisible ink that could be read when rinsed with lemon juice or acid; a symbol in one corner indicated which to use.

On May 21, 1779, Peggy sat down with Arnold in a bedroom of their Market Street house and pored over the pages of the 21st edition of Bailey’s Dictionary. (Andre had preferred Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, but they had rejected it as too cumbersome.) According to Stansbury, they used one of two copies of the compact dictionary: “This I have paged for [them], beginning at A…. Each side is numbered and contains 927 pages.” The Arnolds added “1 to each number of the page, of the column, and of the line, the first word of which is always used, too. Zoroaster will be 928.2.2 and not 927.1.1. Tide is 838.3.2 and not 837.2.1.”

It usually took 10 days for Stansbury to slip through to Andre in New York, and as long to return; late at night he would send a servant to the Arnolds, and Peggy would carefully decode the message and encode Arnold’s reply. Only rarely did the Loyalist Stansbury see the general; almost always he dealt with Peggy. Andre had instructed Stansbury to deal with “the Lady.” In October 1779, when the British at first failed to meet Arnold’s terms, Peggy wrote a cryptic letter in code to Andre and kept the negotiations alive until the two principals struck their bargains. This time she sent her note with a British prisoner who was being exchanged and returned to New York. She had become far more than an unwitting go between, as historians have tended to portray her; she was now an active coconspirator:

Mrs. Moore [Moore was one of Arnold’s code names) requests the enclosed list of articles for her own use may be procured for her and the account of them and the former [orders] sent and she will pay for the whole with thanks.

The shopping list, evidently not the first, included cloth for napkins and for dresses, a pair of spurs, and pink ribbon.

Andre, who had feigned indifference in recent messages, became alarmed. He saw through Peggy’s list: Although the negotiations with her husband had been fruitless so far, she was telling Andre that they were not hopeless. He put aside her shopping list and informed Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in chief, that Arnold had finally stated his price: As Stansbury had told Andre, £20,000 if he succeeded; £10,000 if he failed. What Clinton wanted was detailed plans of West Point, the new American stronghold 50 miles up the Hudson from British lines. Andre sent the proposal back to Peggy, referring to her list as “trifling services from which I hope you would infer a zeal to be further employed.”

It was late October before Andre received another coded note from Peggy:

Mrs. Arnold presents her best respects to Captain Andre, is much obliged to him for his very polite and friendly offer of being serviceable to her.

To entice the British, the Arnolds sent much vital military and political intelligence through the lines in the 17th months from May 1779 through September 1780. In June 1779 they tipped off the British commander that Washington would leave his base at Morristown, New Jersey, as soon as the first hay was harvested and move north to the Hudson for a summer campaign. This leak gave Clinton time to strike first up the Hudson before Washington could reinforce his forts there. The couple disclosed that Congress had decided to all but write off Charleston, South Carolina, the largest and most important town in the South, if the British once again attempted to take it. (They did and succeeded.)

The Arnolds also informed Clinton about American currency problems and about congressional refusal to give agents in Paris full power to negotiate a peace treaty with Britain: The Arnolds believed the French alliance was shaky, and that if it fell apart, the Americans would have to sue for peace. Arnold thought he could then be useful in bringing about a reconciliation between responsible Americans and the British. “I will cooperate with others when opportunity offers,” he wrote, adding a postscript: “Madam Arnold presents her particular compliments.”

Ironically, one of the Arnolds’ early messages to the British led to the interruption of his court-martial in June 17, 1779, soon after it finally began, when the British took his advice and attacked up the Hudson. As Washington and his army dashed north, Arnold lurked behind at headquarters, talking to other officers about Washington’s plans for the season of war. The Arnolds encoded top-secret information about American troop strengths, dispositions, and destinations. He was the first to warn the British of an American expedition “to destroy the Indian settlements” of Pennsylvania and New York. But his most devastating tips were dispatched on July 17, 1779: the latest troop strengths; expected turnout of militia; the state of the army; the location of its supply depots; the number of men and cannon on the punitive raid against the Mohawks; troop locations, strengths, and weaknesses in Rhode Island and in the South; the location and movements of American and French ships. Peggy Shippen met alone with Joseph Stansbury during these treacherous July 1779 negotiations as Benedict Arnold showed the British what he was willing to give in exchange for a red uniform and at least £10,000.

More months dragged by before Washington could spare general officers to reconvene Arnold’s court-martial. Meanwhile, Arnold had resigned as military governor of Philadelphia. Not until December 1779 was he allowed to defend himself, and although the generals recommended a formal reprimand, the Arnolds did not learn of his conviction until April 1780, only weeks after the birth of their first child. He never forgave Washington for publicly censuring him in writing. But Washington considered it a minor affair and promptly offered Arnold another field command, this time as his number two general.

The Arnolds were determined to defect, and Arnold himself put it in writing to Andre and Clinton that West Point would soon be his to command and his to betray to the British. But Washington insisted that Arnold join him with his troops. Peggy was at a dinner party at the home of Robert Morris when news reached Philadelphia that Arnold had been appointed to command the left wing of the Continental Army, not West Point. She fainted.

What Peggy did not learn for three weeks was that Arnold, pretending his old injuries had flared up, had finally persuaded a puzzled Washington to rewrite his orders, installing him as the commandant of West Point and an enlarged New York command. Arnold arrived at West Point on August 4, 1780.

He sent word to Peggy in Philadelphia to leave his sons by his first marriage in the care of his sister and to come by carriage with the baby and her two servants. Meanwhile, he went about weakening West Point defenses (by deploying men so they could not defend against the British) and arranging the details of his defection with Major Andre, who had been promoted to chief of the British secret service inside New York City. Plans for a first meeting on the Hudson on September 11, 1780, miscarried, and Arnold was almost killed by gunfire from a British gunboat.

After two months apart from her husband, Peggy at last arrived at West Point, and their days and nights took on the added excitement of plotting their defection. Peggy’s weeks without Arnold, the longest she had ever been away from him, had been one of the loneliest periods of her life, filled with desperate anxiety. But the same day she rejoined him, they received a letter cutting short the time they could expect together. Washington was coming north from his New Jersey headquarters, he wrote Arnold secretly. Arnold was to provide an escort and meet him as he rode without his army to confer with the French in Hartford.

Realizing how vulnerable Washington would be, Arnold sent off an urgent message to Andre: If the British moved quickly, their warships on the Hudson, helped by a few hundred dragoons, could capture Washington and his generals as he crossed the river with a few score troops. In a bold military coup, Arnold would seize Washington and negotiate an American surrender that would quickly end the war. If the plot succeeded, Arnold could expect a dukedom from a grateful king, and Peggy would be a duchess.

PEGGY’S FIRST AND ONLY SUNDAY AS THE MISTRESS OF WEST POINT, September 17, 1780, was a tense affair. Arnold’s staff fled into the wainscoted dining room of Beverley, the commandant’s house, to take their seats with Arnold’s weekend Loyalist houseguests. It was an early dinner: Arnold was soon to go downriver to deliver Washington’s hand-picked escort. They were hardly seated when a courier arrived with two coded letters for Arnold from Andre, who was aboard the Vulture, a British ship 12 miles downriver. Trying not to betray his excitement, Arnold pocketed the letters. After dinner he rode off with 40 Life Guards to meet Washington.

Circling back alone that night after his last meeting with Washington, Arnold waited for the British attack, but Clinton procrastinated and it did not come. He had learned, however, that Washington would be inspecting West Point on September 23; the British would have a second chance. Three more anxious days passed at Beverley. Shortly before dawn on September 21, Arnold kissed Peggy good-bye and slipped off to meet Andre. Late that night an open boat bearing Andre, wrapped in a navy blue caped coat, thumped ashore two miles below Haverstraw. At last the two men met. Arnold turned over papers to Andre and returned to West Point on September 22.

While Arnold had been gone, Peggy, still exhausted from her nine-day journey to West Point in an open carriage in the summer heat, had stayed with the baby in Beverley’s master bedroom, a sunny, quiet place with big open windows and balustraded porch. Now, on September 23, a Saturday, she stayed late in the room, planning to go downstairs later when Washington arrived. Arnold and his staff had just been served breakfast when a messenger, muddy and dripping, was shown in: John Andre had been captured!

His luck had run out half a mile north of Tarrytown that morning. Seven young militiamen absent without leave had banded together to way lay Loyalist travelers. As Andre rode up to Pine’s Bridge, he was startled by three of them. John Paulding, in a captured Hessian’s uniform, grabbed the bit of Andre’s horse.

“Gentlemen,” said Andre, who could see the British lines, “I hope you belong to our party.”

“What party?” Paulding demanded.

“The lower party,” Andre replied, alluding to the Loyalists. “Thank God, I am once more among friends. I am glad to see you. I am an officer in the British service.” The exuberant Andre pulled out his gold watch “for a token to let you know I am a gentleman.”

“Get down,” Paulding growled. “We are Americans.”

“My God, I must do anything to get along,” Andre rejoined with a stage laugh, brandishing a pass Arnold had written out for him.

“Damn Arnold’s pass! You said you was a British officer. Get down.

Where is your money?”

When Andre began to argue, Paulding swore and pointed his weapon. “God damn it! Where is your money?”

After Andre protested that he had none, Paulding and his friends forced him into a thicket and ordered him to strip. Andre later said that the three men ripped up the housings of his saddle and the collar of his coat and were about to let him go when one of the party said, “He may have it in his boots.” They threw him down, yanked off his English boots, and, in his stockings, found Arnold’s report of West Point’s fortifications and troop displacements, a summary of the American army’s strength, and the secret minutes of Washington’s latest council of war concerning combined Franco-American strategy.

“This is a spy,” Paulding finally shouted to the others. They prodded him with their guns as he dressed and mounted. Then they tied his arms behind him and led him back over the roads he had just ridden, back toward the American lines.

At West Point, Arnold was handed a note informing him that a packet of papers in his own handwriting was on its way to Washington. He hurried upstairs to Peggy, locked the bedroom door, and whispered that the plot had been discovered. Washington was expected any minute.

Peggy must have reassured her husband that she and the baby would be safe; it is unlikely that she tried to talk him out of fleeing for his life. She agreed to burn all of their papers and stall for time. He embraced her, took a last look at Neddy, and hurried out, ordering an aide to saddle a horse. At the river, Arnold jumped into his eight-oared barge, drew his pistols, and told his crewmen he would give them two gallons of rum if they got him downriver. The boat lurched into the Hudson channel, Arnold in the stem. By the time Washington arrived, a few minutes later, Arnold was on his way to the Vulture and the British lines.

Peggy’s years of studying theatrics now saved her husband’s life, even if her performance could have cost hers. As Arnold was making his escape, she ran shrieking down the hallway in her dressing gown, her hair disheveled. Arnold’s aides rushed up the stairs to find her screaming and struggling with two maids, who were trying to get her back into her room. Peggy grabbed one young aide by the hand and cried, “Have you ordered my child to be killed?” Peggy fell to her knees, the aide later testified, “with prayers and entreaties to spare her innocent babe.” Two more officers arrived, “and we carried her to her bed, raving mad.” The distraught 20-year-old so distracted Arnold’s staff that no one thought to pursue him until Washington arrived.

Peggy Shippen’s world had been exploded by a plot she had encouraged, aided, and abetted, and sheer nervous tension on the day of discovery helped her to completely fool everyone around her. It would be the twentieth century before the opening of the British Headquarters Papers at the University of Michigan proved what the eighteenth century refused to believe–that a young and innocent–appearing woman was capable of help ing Benedict Arnold plot the conspiracy that nearly delivered victory to England in the American Revolution.

When Peggy learned that Washington had arrived, she cried out again and told the young aides that “there was a hot iron on her head and no one but General Washington could take it off.” The aides and a staff doctor summoned the commander in chief, but when Peggy saw him she said, “No, that is not General Washington; that is the man who was going to assist…in killing my child.” Washington retreated from the room, certain Peggy Arnold was no conspirator. A few days later he sent her and the baby under escort to her family in Philadelphia.

When news of Arnold’s treason spread throughout America, Peggy was ordered expelled from Pennsylvania. The same officials whose hounding of Arnold had provoked him into treason now unwittingly aided her escape through British lines to join the traitor in New York City. She arrived at Two Broadway, the house Arnold had rented next door to British headquarters, in time to learn that John Andre had been hanged by Washington after a drumhead trial for espionage. She secluded herself in her bedroom for weeks, rarely appearing with Arnold at headquarters functions.

Paid £6,350, Arnold was commissioned a British brigadier general. He raised a regiment, the American Legion, made up exclusively of deserters from the American army–no British officer would serve under him–and led it on bloody raids through Virginia. Arnold’s troops sacked the capital at Richmond, nearly capturing Thomas Jefferson, and his native Thames River valley of Connecticut.

Peggy spent the last year of the Revolution, her last year in her native country, a celebrity in New York, pregnant much of the time with her second child. Some of her old Philadelphia neighbors were also Loyalists living in British-occupied Manhattan; her former Society Hill neighbors kept tabs on her and wrote back news to Philadelphia.

Peggy was grieving for Andre, even though her marriage to Arnold was serene. Mrs. Samuel Shoemaker wrote in November 1780 that Peggy now “wants animation, sprightliness and fire in her eyes.” When she did appear in public, however, it was as the new favorite at headquarters balls. Peggy “appeared a star of the first magnitude, and had every attention paid her,” especially after she received a personal pension of £500 a year from the queen. After the British surrender at Yorktown, where American troops celebrated victory by burning Arnold in effigy, the Arnolds sailed for England in a 150-ship convoy. They arrived on January 22, 1782, and according to the Daily Advertiser took “a house in Portman Square and set up a carriage.” She was, wrote one nobleman, “an amiable woman and, was her husband dead, would be much noticed.”

The Arnolds’ warmest reception was at the Court of St. James’s, where they were introduced to the king and queen. Arnold, King George III, and the Prince of Wales took long walks together, deep in conversation. Queen Charlotte was especially taken with Peggy, and her courtiers, as one wrote, paid “much attention to her.” The queen doubled Peggy’s pension to £1,000 a year and provided a £100 lifetime annuity for each of her children. Peggy was to raise five, and eventually received far more from the crown than Arnold did. Her pensions guaranteed that she could bring up her children comfortably and that based on their mother’s prestige alone they would be introduced into society as English gentry. All four of the Arnolds’ sons became British officers; their daughter married a general.

Arnold never got another farthing. When peace came, he became a half-pay pensioner and had to strap family resources to build a ship and return to the life at sea that had once made him wealthy. As her husband sailed to Canada, Peggy, 25 years old, suddenly felt the loss of her American home and family. Arnold was gone for nearly a year and a half, during which Peggy ran their business affairs, collected and invested their pensions, and fought lawsuits. When he returned, she had to pack every thing up again–this time they were moving to Saint John, New Brunswick, where Arnold had established a shipping business, was buying up land, and had built a general store. Late in 1787, only six weeks after they arrived in Canada, Peggy gave birth again.

For the first time since she left Philadelphia, Peggy was able to make close friends. She lived in a big gambrel-roofed clapboard house elegantly decorated with furniture Arnold brought from England. But the house was an opulent island in a sea of deprivation: The city was crowded with impoverished Loyalist refugees, and few people could afford to pay Arnold for his imported goods. He made new enemies as he faced frequent decisions about whether to sue or to put men in debtors’ prison. When his warehouse and store burned, there were whispers that he had torched them for the insurance. A former business partner was one of his accusers, and when Arnold confronted him, the man said, according to the court record, “It is not in my power to blacken your character, for it’s as black as it can be.”

The insult directly resulted in the denial of Arnold’s insurance claim and in the first jury trial for slander in New Brunswick history. Arnold won, but instead of the £5,000 he sought, the judges based the award on the value of his reputation and gave him only 20 shillings, an unbearable insult. At the same time, a mob sacked the Arnolds’ home. Peggy and the children were away at the time, safe. After five years in Canada, the Arnolds moved back to England.

Like many Loyalists, Peggy Shippen Arnold planned to return one day to live in the United States, where she kept her inheritance invested in Robert Morris’s Bank of the United States. However, when she went to visit her ailing, aged mother, she was menaced by sullen mobs who refused to forgive her husband. The arrival of the traitor’s wife in Philadelphia, even as Congress was deliberating the new Constitution, stirred controversy. Her brother-in-law recorded that she was treated “with so much coldness and neglect that her feelings were continually wounded.” Old friends said her visit placed them “in a painful position.” Others whispered that “she should have shown more feeling by staying away.” After a five-month visit, Peggy left her family forever.

Benedict Arnold’s final years were occupied with a long string of business misadventures and also with his obsessive defense of his reputation. He expanded his Caribbean operations, in his last eight years sending or sailing 13 different ships on trading voyages. Often offended publicly, he fought a duel with the earl of Lauderdale, who had insulted him on the floor of the House of Lords. Peggy wrote to her father that the days before the duel were filled with “a great deal of pain.” She “had not dared to discuss the duel with the silent general,” fearing that she would “unman him and prevent him acting himself.” When fought, the duel produced no casualties, but it “almost at last proved too much for me, and for some hours, my reason was to be despaired of.”

As a new war with France spread over the world, Arnold outfitted his own privateering ship to attack French shipping in the Caribbean. This time he was gone 18 months, agonizing months for Peggy, who learned that her husband had been captured by French revolutionaries and had managed to escape only shortly before his scheduled execution. When Arnold returned and she again became pregnant, Peggy’s health began to decline. On December 5, 1795, she wrote to friends in Canada: “For my own part, I am determined to have no more little plagues, as it is so difficult to provide for them in this country.”

For years Peggy lived in dread that the queen would die and her pensions would stop–a legitimate fear, made worse after her husband’s captains defrauded them of some £50,000 and she had to sell her American investments to bail him out. In 1801, at age 60, Benedict Arnold became dispirited and, after a four-month illness, died “without a groan.” Peggy, oppressed by his creditors and stunned by his loss, lived for three more years, long enough to pay off all his debts “down to the last teaspoon.”

“Years of unhappiness have passed,” she confided in a letter to her brother-in-law. “I had cast my lot, complaints were unavailing, and you and my other friends are ignorant of the many causes of the uneasiness I have had.” To her father she wrote that she had had to move to a smaller house, “parting with my furniture, wine and many other comforts provided for me by the indulgent hand of (Arnold’s) affection.” Arnold had paid a final compliment to Peggy’s business acumen by making her sole executrix of his estate, an unusual step at the time. Once she had cleared up the mess he had left and could see that her children would be provided for, she thanked her father for her fine private education: “To you, my dear parent, am I indebted for the ability to perform what I have done.”

Years of anxiety and illness had exacted a terrible toll, and Peggy Shippen Arnold’s quarter-century ordeal in exile ended on August 24, 1804. She had, she wrote, “the dreaded evil, a cancer.” She told her sister she had “a very large tumor” in her uterus. “My only chance is from an internal operation which is at present dangerous to perform.”

Peggy died at 44. After her death, her children found concealed among her personal possessions a gold locket containing a snippet of John Andre’s hair. Family tradition holds that Benedict Arnold never saw it.

Willard Sterne Randall is the author of Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor (1990) and Thomas Jefferson: A Life (1993). He is currently working on a biography of George Washington.

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Winter 1992 issue (Vol. 4, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Mrs. Benedict Arnold

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!