His paternal grandfather had fought against the South, and his father against Spain and Germany, so it was reasonable to assume James Maitland Stewart would serve in his turn. By the late 1930s, his career was just taking off with such hits as You Can’t Take It With You, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Destry Rides Again. But with war looking inevitable, Stewart set his sights on a new role, this time in the U.S. Army Air Corps. He even bought his own plane, a Stinson 105, eventually graduating to multi-engine aircraft and earning a commercial pilot’s license, all on his own.

Stewart’s draft number was 310, but though he was 6-foot-3, he weighed only 138 pounds. When the Army turned him down as too skinny, he started eating spaghetti twice a day, supplemented with steaks and milkshakes. At a second physical in March 1941, he still hadn’t gained quite enough weight to be eligible, but he talked the Army doctors into adding an ounce or two so he could qualify, then ran outside shouting to fellow actor Burgess Meredith: “I’m in! I’m in!”

The night before he left for training, MGM threw a farewell party for its departing star. Most of the actresses present that evening kissed him goodbye, and Rosalind Russell wiped off the lipstick with her handkerchief and wrote each girl’s name on it. Stewart kept the hanky for good luck.

On March 22, 1941, Stewart was inducted into the Army as a private, serial number 0433210. He was sent to Fort MacArthur, Calif., where cameramen hounded him, following him even when he was issued his underwear. Witnessing all that unwanted attention, one old soldier remarked sympathetically, “You poor bastard.” Stewart’s salary dropped from $12,000 per week to $21 per month, but he dutifully sent a 10 percent cut ($2.10) to his agent each month.

Stewart underwent basic training at Moffett Field, Calif., where a crowd of girls waited just outside the gates, eager to get a glimpse of their idol. It got so bad that his commanding officer put up a sign requesting civilians to leave Stewart alone until after he finished his training. He was commissioned on January 18, 1942. Appearing in uniform at the Academy Awards the following month, he presented the Best Actor Oscar to Gary Cooper for Sergeant York (Stewart had won the previous year for The Philadelphia Story).

Though Stewart subsequently narrated two training films, Fellow Americans and Winning Your Wings, and lent his star power to a few radio shows and war bond tours, in general he resisted efforts to capitalize on his career. Instead he requested more flying time—and he soon got his wish. First he became a flight instructor in Curtiss AT-9s at Mather Field, Calif. From there he went to Kirkland Field, N.M., for six months of bombardier school. In December 1942, he requested transfer to the four-engine school at Hobbs, N.M. Finally, he reported to the headquarters of the Second Air Force in Salt Lake City.

Still looking for more than desk duty, Stewart was sent to Gowen Field in Boise, Idaho, and the 29th Bombardment Group, where he became a flight instructor on B-17 Flying Fortresses. During that time, his roommate was killed in an accident, and three of his trainees were lost in another mishap. One student remembered, “Stewart was known for being one of the few officers who never left the airfield tower until every single plane had returned.”

On one night flight with a student pilot, Stewart left the copilot’s seat to check on equipment in the nose and let a new navigator sit in the right-hand seat. Suddenly the no. 1 engine exploded, sending pieces of shrapnel into the cockpit and knocking the pilot senseless. With the engine on fire and wind tearing through the windows, the navigator froze at the controls. Stewart had to pull him out of the seat so he could take over, hit the fire extinguishers and land on three engines.

In March 1943, Stewart briefly became the operations officer of the 703rd Squadron, 445th Bomb Group, in Sioux City, Iowa. He was named the squadron’s commander three weeks later.

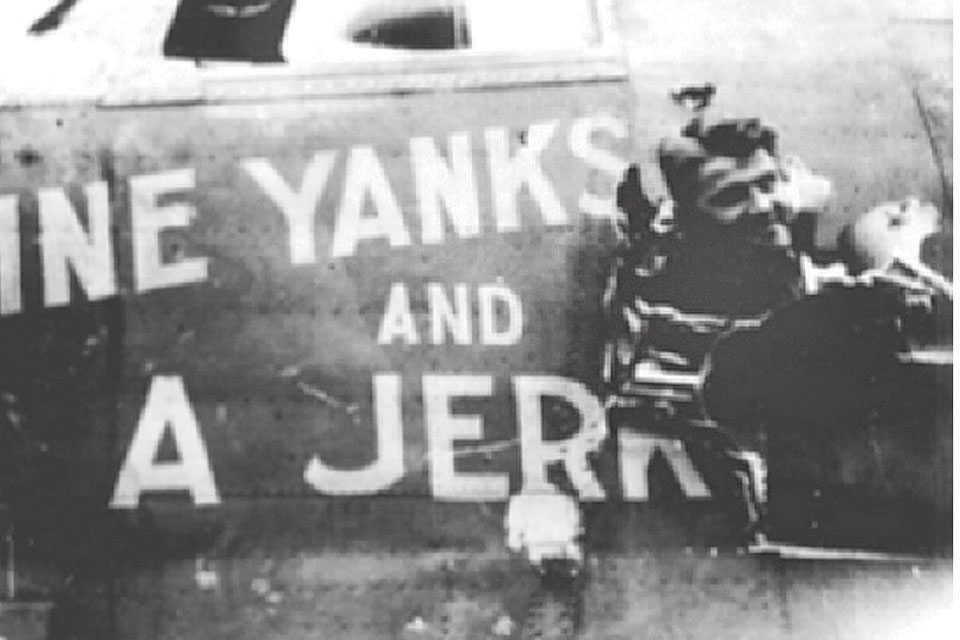

On November 11, Captain Stewart led two-dozen B-24H Liberators to England by way of Florida, Brazil, Senegal and Morocco. They became part of the 2nd Air Division, Eighth Air Force, stationed at Tibenham. Within hours of their arrival, Germany’s “Lord Haw-Haw” welcomed the squadron on the radio. Following a few shakedown flights, Stewart’s first mission was to bomb the naval yards at Kiel, flying a B-24 that had been named Nine Yanks and a Jerk by a previous crew.

The actor-turned-commander was a successful, popular officer. His roommate at the time recalled: “I always got the feeling that he would never ask you to do something he wouldn’t do himself. Everything that man did seemed to go like clockwork.”

Stewart was lucky, too. During his third mission, on Christmas Eve, his group was ordered to hit V-1 launching sites at Bonnaires, France. Coming in low at 12,000 feet, 35 B24s plastered the target near the coast, then returned to base without even being targeted by flak or fighters. If two of the Liberators hadn’t collided on takeoff, it would have been a perfect mission.

He also took care of his men. When Stewart found out the finance officer wouldn’t have enough money for his crew for a few days, he threatened to have him transferred to the infantry unless they were paid immediately. And when one of his crews hid a keg of stolen beer in their barracks, he ambled in, threw off the covers and drew himself a glass, then announced that there was a keg of beer around there somewhere, it was a very serious matter and it should be taken care of immediately…if they ever found it. He then finished his beer and walked out.

In January 1944, Stewart was promoted to major, a promotion he had refused until, as he said, “my junior officers get promoted from lieutenants.” By that time he commanded all four squadrons of the 445th Bomb Group.

On January 7, after bombing Ludwigshafen, Stewart noticed that the lead group, the 389th, was 30 degrees off course and slowly diverging from the protective fire of the rest of the formation on the way back to base. Knowing the bombers’ new direction would take them directly over Luftwaffe airfields in northern France, he radioed the lead plane and explained they were off course. The leader replied curtly that no, they weren’t, “and stay off the radio.”

Stewart faced a difficult decision. He could stay with the rest of the formation on the correct course, or he could follow his errant lead squadron. A two-squadron formation would be much more vulnerable, but a single squadron didn’t have much of a chance at all. He chose to stay with the 389th and add the defensive power of his own guns to theirs.

Sure enough, more than 60 Luftwaffe planes swarmed up from bases below. The commander of the 389th Bomb Group paid dearly for his mistake: his plane went down in flames. Seven other 389th B-24s were also shot down, but Stewart was lucky again; all the bombers in his squadron made it home. As a fellow officer would later point out, “There were a lot of lives saved that day because he knew what he was doing and when he had to do it.”

Stewart experienced what was probably his closest brush with death on February 25, during a nine-hour mission to Furth, unescorted most of the way. For the first time, waist gunners in the lead planes hurled bundles of chaff overboard to try to fool the German radar-directed anti-aircraft guns. It only succeeded in attracting them. Whenever they threw a bundle out, the flak became more accurate. The Germans hit the bombers with everything they had on that mission, including anti-aircraft rockets.

The 445th hit its target, but on the way home a flak shell burst in the belly of Stewart’s Liberator, directly behind the nose wheel. Somehow the B-24 kept on flying—all the way back to base. But when the shrapnel-perforated bomber landed, its fuselage buckled. Just in front of the wing at the flight deck, the airplane cracked open like an egg. The crew climbed out, unhurt, and looked over their crippled aircraft. In his characteristically understated fashion, Stewart mused to a bystander, “Sergeant, somebody sure could get hurt in one of those damned things.”

Aside from an occasional trip to actor David Niven’s house, a meeting with a dignitary or a quick sailing expedition, Stewart concentrated on the job at hand. “I prayed I wouldn’t make a mistake,” he recalled. “When you go up you’re responsible.” Once a flight engineer went AWOL just before a mission, forcing his plane to fly without him. It didn’t return. Stewart was required to discipline the man, but he wondered, “How do you punish someone for not getting killed?”

The war eventually got to everyone, even calm, mild-mannered Jimmy Stewart. “Fear is an insidious thing,” he said. “It can warp judgment, freeze reflexes, breed mistakes. And worse, it’s contagious. I felt my own fear and knew that if it wasn’t checked, it could infect my crew members.”

In early 1945, after 20 B-24 missions, Stewart was transferred to Old Buckenham, becoming the operations officer of the 453rd Bomb Group. When he arrived in a B-24, he reportedly buzzed the tower until the controllers fled.

The 453rd’s lead Liberator, Paper Doll, had no permanently assigned copilot. That position was usually filled by one of the senior staff officers, often Stewart himself. Waist gunner Dan Brody recalled, “He exhibited himself as an excellent pilot, even under adverse conditions.”

Like the men of the 445th, his new group found Stewart unfailingly friendly. On the way back up the runway, for example, when he saw a pedestrian he’d stop his jeep and drawl, “Hey fella, lak a ride?”

The senior staff normally rotated, flying every fifth mission, but Stewart went out of his way to lead 11 more sorties. While he liked the B-17, he still had a soft spot for the Liberator. He later said of the B-24, “In combat, the airplane was no match for the B-17 as a formation bomber above 25,000 feet, but from 12,000 to 18,000 it did a fine job.”

Most of the men were amused to find they were being briefed by the famous actor. Extras often dropped in—among them radioman Walter Matthau, who thought he “was marvelous to watch.”

In April 1945 Stewart was promoted to colonel and chief of staff of the 2nd Air Division. It was during this time, while he was sweating out the return of his planes from each mission, that his hair began to turn gray.

Stewart finally returned Stateside in September 1945 aboard the liner Queen Elizabeth. Predictably, he waited at the gangplank until all of his men had disembarked before coming ashore. Asked about his service in Europe, he commented, “I had some close calls—the whole war was a close call.” When he returned to Hollywood, he refused a lavish welcome home party, saying, “Thousands of men in uniform did far more meaningful things.”

A standard clause in Stewart’s contracts thereafter stipulated that no mention of his war record could be used in conjunction with any of his films. He remained in the Air Force Reserve, and in 1955, persuaded by friends, made the film Strategic Air Command. Ironically, though he had thousands of hours in the air, because of studio insurance regulations Stewart wasn’t allowed to actually fly in any of his movies.

In 1966 Stewart made one more combat flight—this time as an observer in a B-52 Stratofortress over North Vietnam. His stepson Ronald McLean was killed in Vietnam one year later.

During an interview late in life, the actor explained that World War II was “something I think about almost every day—one of the greatest experiences of my life.” Asked whether it had been greater than being in films, he said simply, “Much greater.” James Stewart—recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal with Oak Cluster, the Croix de Guerre with Palm and seven Battle Stars—died on July 2, 1997, at age 89.

Freelancer Richard Hayes writes from Chicago. For further reading, try Jimmy Stewart: Bomber Pilot, by Starr Smith.

Mr. Stewart Goes to War originally appeared in the March 2011 issue of Aviation History Magazine. Subscribe today!