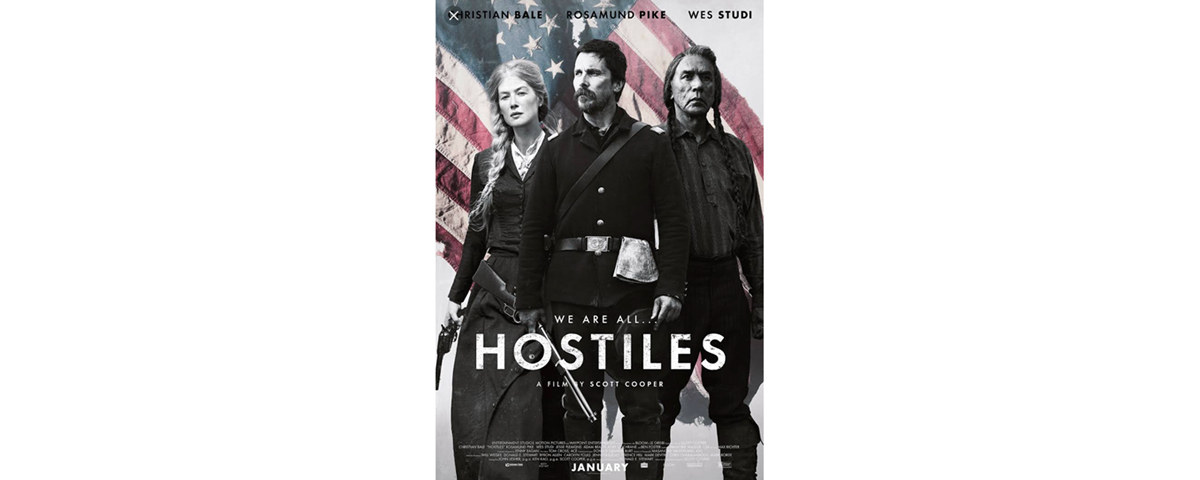

Hostiles, 2017, 133 minutes

Director Scott Cooper’s fourth feature is an excellent, if occasionally languid and episodic, Western that tackles post-traumatic stress disorder and the toll of war on the frontier. A cavalryman with an impeccable, if ruthless military record of killing Indians, Captain Joseph Booker (Christian Bale) is tasked with transporting a dying Cheyenne prisoner, Chief Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi), to Montana Territory so he may die on his tribal lands. Booker initially tries to decline the mission, calling Yellow Hawk “a butcher” (it seems the chief has an equally impeccable, ruthless record of killing whites), but he eventually accepts, and the two former combatants hit the trail. Joined by Yellow Hawk’s family and a small, handpicked group of soldiers, Hostiles takes the basic shape of a road movie—albeit a grim and humorless one (think more The Road than Midnight Run).

Shortly after departing, the group takes on a woman, Rosalie Quaid (Rosamund Pike), whom they find in a cabin burnt to a crisp by Comanches, her husband and three children lying dead around her. With the Comanche raiding party hot on their trail, Booker also agrees to transport a second prisoner, Sergeant Charles Wills (Ben Foster), who’s being sent to hang after murdering Indians on a Colorado reservation. Wills previously rode with Booker in the cavalry and feels he’s being made an example of for doing what they’ve done together for years behind the safeguard of a U.S. Army uniform. He tells Booker, “We both know it could just as easily be you wearing these chains.”

The story goes where one would assume, the racist Booker having some sort of cultural awakening—gaining respect for Yellow Hawk and his tribe, while experiencing deep remorse for his role in the Indian wars. The “white man’s redemption” story is nothing new to cinema or the genre, but the character transformations feel earned, the antiwar messages poignant and never preachy.

Bale, meanwhile, is something to behold as the buttoned-up and traumatized captain. The totality in which he depicts a man on the verge of bursting at the seams is striking. His uniform, its collar often clasped tightly around his neck, always seems to be suffocating him. A pool of rage and frustration marinates underneath it, and he spends every ounce of soldierly restraint he has left trying to contain it. But whereas Bale’s Booker keeps his traumas bottled up, Pike’s Rosalie lets hers gush out in streams of fury and disillusionment—she finds her grief impossible to contain. Their performances were two of the best in 2017.

The film’s beautiful final shot seems to play as a counter to the closing shot in John Ford’s The Searchers—perhaps the most iconic image in Western cinema (neck and neck with the crane shot from High Noon)—in which John Wayne wanders away from the ranch house and into the desert, having been sufficiently quarantined from society. In Hostiles Booker does enter the ranch house, so to speak, but the question remains the same: Can the butcher ever really return from war?

—Louis Lalire