From a landing ship out on the Philippine Sea, Frank Borta, Rich Carney, and the other 190 members of the 1st Battalion, 29th Marine Regiment (Reinforced), watched smoke rise above Saipan. The clouds had been billowing for nine hours.

Since dawn on June 15, 1944, Japanese batteries on Saipan had been trading salvos with American warships east of the island. Periodically Marine Corsairs and navy Hellcats strafed the beaches and hills. Torpedo planes lashed the defenders with rockets. Despite a rain of enemy rounds and relentless gunfire by Japanese troops in bunkers and foxholes overlooking the beaches, hundreds of amtracs—amphibious armored vehicles that ferried Marines from LSTs, or tank landing ships, to shore—had landed thousands of men of the 4th and 2nd Divisions under the command of Marine Lieutenant General Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith.

To Borta, Saipan looked like a giant serpent bursting from the sea. The crest of the snake’s spine was Mount Tapotchau, the grand prize—provided 1st Battalion could get there as assigned, capture it, and hold it. American intelligence reported 15,000 Japanese garrisoned on the heavily fortified island.

It was nearly 3 p.m.—time for the 1st Battalion to make the 4,000-yard trip into battle. Once Marines packed the LST’s 17 amtracs, navy men lowered the ramps and the lightly armored vehicles, tracks whirring, churned toward shore. Borta confessed to his buddy that he was petrified.

“Stick with me, Chick,” chuckled Carney, who had been a Golden Gloves boxer. “There isn’t a Jap mother who has a son that can kill Mrs. Carney’s boy.”

Borta hoped Carney’s good luck was contagious.

.jpg) Saipan was twice the size of Manhattan: 14 miles long, and at most 6 miles across. Home to 25,000 Japanese and native civilians, it was shaped like a pistol aimed at Tokyo. On the pistol grip, scene of the landing, stood Charan Kanoa, one of two main towns and the site of a dock and sugar refinery. The 4th Division had landed south of the dock; 2nd Division had landed north. The 1st Battalion—which its troops called the Bastard Battalion, because it had been cobbled together from several Marine units—was to come ashore north of the dock as well, at Green Beach 2, and attach to 2nd Division’s 8th Regiment.

Saipan was twice the size of Manhattan: 14 miles long, and at most 6 miles across. Home to 25,000 Japanese and native civilians, it was shaped like a pistol aimed at Tokyo. On the pistol grip, scene of the landing, stood Charan Kanoa, one of two main towns and the site of a dock and sugar refinery. The 4th Division had landed south of the dock; 2nd Division had landed north. The 1st Battalion—which its troops called the Bastard Battalion, because it had been cobbled together from several Marine units—was to come ashore north of the dock as well, at Green Beach 2, and attach to 2nd Division’s 8th Regiment.

Borta wasn’t kidding about feeling scared. He had enlisted at 16—“Chick” came from “spring chicken”—by getting his mother in Chicago to lie to a recruiter. He still wasn’t 18. To keep him safe his mom had given him a cross, which he laced to his dog tags with phone wire. He rubbed the cross with his thumb as he looked at Mount Tapotchau.

Tapotchau was the key to Saipan. And Saipan was the key to the Marianas, a chain of 15 volcanic islands 1,100 miles north of New Guinea and 1,260 miles south of Tokyo. Admiral Ernest King, commander in chief of the United States Fleet and chief of naval operations, believed capturing the Marianas, which included Guam and Tinian, would spell victory in the Pacific. From these islands, the American navy could cut enemy supply routes and lay siege to Japan. Meanwhile the air force’s B-29 Superfortress, which had a 1,500-mile combat range carrying more than four tons of bombs, could devastate Japanese cities.

Saipan would be Chick Borta’s second landing. The November before, he and many of the Marines now in the Bastard Battalion had been with other outfits that helped take Tarawa. From that experience—the first pitched battle between entrenched Japanese defenders and an American amphibious force—Borta knew to expect the stink of diesel fumes and exhaust aboard the amtrac, and the way the ungainly craft vibrated as it crawled toward shore. No wonder they called the clunky things alligators.

In the first four days on Tarawa, 6,000 men on both sides died. Chick saw less than some of his new buddies had. Sharp-eyed, skinny Californian Glenn “Pluto” Brem, who once hit 326 bull’s-eyes out of 340 shots in a 12-knot wind, did lots of real shooting there with his Browning Automatic Rifle. Bronx-born, Hollywood-handsome Rich Carney was up for a Silver Star; he took out a bunker. Borta came ashore late on the second day, missing Tarawa’s bloodiest hours, but he saw all the combat he needed to memorize the whip-crack of a .25-caliber Arisaka rifle and the thud of a Model 92 heavy machine gun.

On Tarawa, Chick Borta learned that it paid to gulp hydration mixture—a foul cocktail of salt and water formulated to keep men from passing out—and to keep his feet clean and dry or risk jungle rot, a fungus that made your dogs feel as if they were on fire. He also learned that when it came to knocking down attackers, the heavier M1 Garand rifle beat the lightweight .30-caliber M1 carbine. Dusk to dawn, Borta and other Marines stayed on edge, bayonets ready: the Japanese were superb night fighters, able to slither in and slit a throat or disembowel a man without a sound. After Tarawa, the surviving Marines were sent to Hawaii. Some stayed in Hilo, while others went to a mountain location they wryly called Camp Tarawa to recuperate, often from dengue fever or infected coral cuts, and train for the next landing.

Sergeant John Rachitsky, an old China Marine, had been on Guadalcanal and Tarawa, and at Camp Tarawa. Now he was leading the platoon in 1st Battalion’s A Company that included Brem, Carney, and Borta. Green as Chick was, Rachitsky had tapped him to be a runner once they landed.

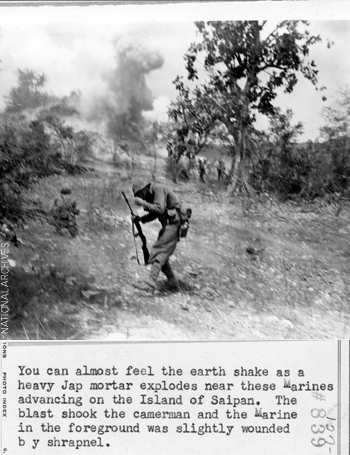

The amtrac chewed water, closing on the beach. To keep Saipan, the Japanese would have to drive the Americans back into the sea. So far it had not worked, but batteries of 6-inch coastal guns, 75mm mountain guns, and 150mm mortars were working overtime to support troops in blockhouses and rifle pits. And, although the Americans did not yet know it, their intelligence was wrong. There were not 15,000 Japanese troops but 30,000—including a mountain defense force at Tapotchau.

Green Beach 2 was supposed to be secure, but enemy artillery opened up as 1st Battalion’s amtracs roared into the lagoon. Soon Japanese gunners had zeroed in on the strand. When a round wiped out one of the lead amtracs, Chick Borta tasted the acidic burn of fear. Less than a minute later, his platoon’s amtrac dug its treads deep into the sand.

“Let’s go, men!” Rachitsky shouted as the machine came to a halt. “Let’s get the hell out of this coffin!”

Shell fragments slapped at the vehicle. Borta jumped to his feet. He wanted out before a round blew the amtrac apart. The Marine ahead on the gunwale teetered and fell back, almost knocking Chick over. He reached to help—until he saw the hole in the guy’s head and the blood at his mouth. Seconds later Borta was tumbling onto the sand, surrounded by damaged and burned amtracs, discarded packs, shattered trees, and mangled bodies.

Rachitsky said they had new orders—move south toward the sugar refinery to assist the 8th Marines. To confirm the change, Rachitsky sent Borta to headquarters, a quarter mile back. As he was weaving among the shell craters and foxholes he heard a familiar voice. Carney, crouched in a foxhole, had his helmet tilted low, obscuring most of his face, but there was no mistaking that grin. Borta slowed to a trot.

“Hot, eh, Chick?” Carney cracked, pushing his helmet back. Too winded to speak, Borta kicked sand Carney’s way and ran on. “You sonofabitch!” Carney yelled.

Borta got the orders confirmed and made his way back. Rachitsky and the rest were crowding a crater 50 feet off the beach, in a grove of coconut palms. “Yup,” Borta said. “The sugar factory.” The plant, 80 yards down the beach, was completely exposed. Borta looked at Rachitsky. Rachitsky nodded. “Ready!” the sergeant said, taking off with Borta 20 feet behind.

An incoming round shrieked. “Close!” Borta yelled as they all dove to the ground. The shell landed between him and Rachitsky. Borta felt a blast, then warm liquid on his leg. Rachitsky was staring down at him. “C’mon!” the sergeant yelled. “I can’t,” Borta groaned. “I’m hit.” Rachitsky knelt and felt Borta’s leg, shook his head, and said, “Look.” Borta winced and glanced down. His dungarees were soaked, but what he had thought was his blood was…salt water. Shrapnel had perforated his canteen.

An incoming round shrieked. “Close!” Borta yelled as they all dove to the ground. The shell landed between him and Rachitsky. Borta felt a blast, then warm liquid on his leg. Rachitsky was staring down at him. “C’mon!” the sergeant yelled. “I can’t,” Borta groaned. “I’m hit.” Rachitsky knelt and felt Borta’s leg, shook his head, and said, “Look.” Borta winced and glanced down. His dungarees were soaked, but what he had thought was his blood was…salt water. Shrapnel had perforated his canteen.

Dripping hydration mixture, Borta raced after Rachitsky. Twice rounds landed near enough to spin him. Each time, as soon as the dock came back into focus he was off again at a gallop.

The eight men reached the factory and dove into a ditch, not realizing they had run beyond the 8th Marines and into no man’s land. Their mistake became clear after dark, when machine gunners on both sides opened up and the opposing forces, trying to spot one another, fired flares. Tracer rounds ripped past directly overhead as competing flares hung in the sky, drenching the battlefield in yellow light. Borta felt for his cross. It was gone.

“Fix bayonets,” Rachitsky whispered. Borta heard clicks as men checked and re-checked their bayonets. He was glad he had sharpened his at sea. “Let ’em come,” he thought. Instead, the night crawled by. When he heard fruit bats returning to their perches after a night of feeding and felt sun on his face, Borta knew the Japanese had missed their chance. “Let’s get the hell out of here,” Rachitsky grumbled.

The men moved slowly through the front lines of the 8th Marines. To keep from getting shot, they announced themselves the entire way. “29th Marines, 1st Battalion,” they chanted. “29th Marines, 1st Battalion.”

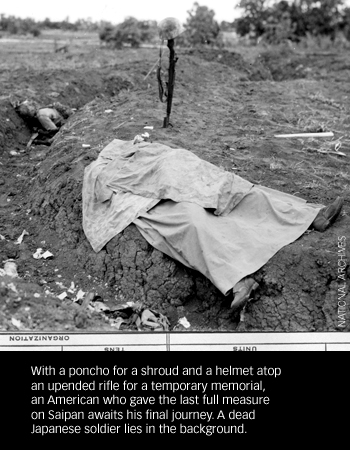

At the beach, the smell of burned flesh had Borta reflexively clenching his throat. Ponchos covered most Marine corpses. Fat flies moved in sluggish clouds from one dead man to the next. Walking wounded in blood-splattered dungarees wandered by with glazed eyes. Corpsmen hustled among patients, whispering encouragement as they stuffed ruptured chests with cotton balls and applied and tightened dressings and tourniquets. The medics had to work fast; in the heat, wounds quickly became infected.

A man walked up to Rachitsky. Borta overheard him say that the day before, Japanese shelling had killed or wounded 32 men from A Company. Borta wondered aloud where Carney was.

“Carney…,” another Marine said. “He had his head blown off.”

Borta thought of Carney’s quick grin and confidence, but this was no time to meditate or mourn. Their orders were to push east past Lake Susupe and wheel north to help take Tapotchau.

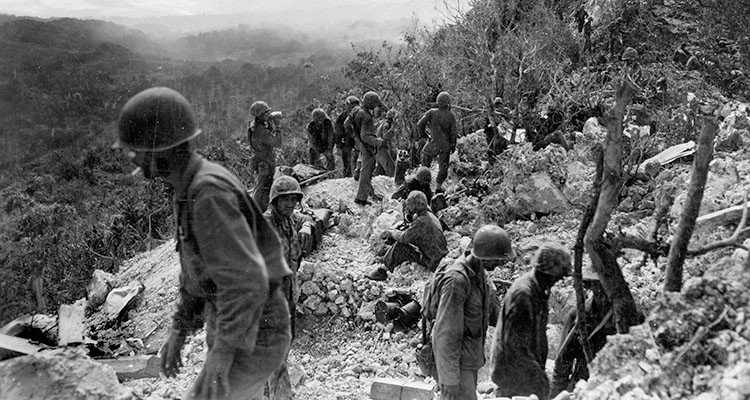

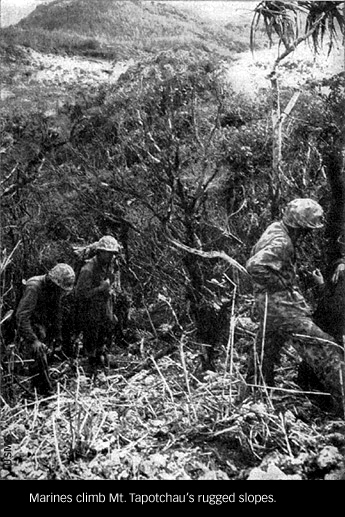

But how? A valley ending in a deep gorge complicated the mountain’s east flank. The south side was nothing but sheer cliffs. To the west lay a tangle of gullies, ravines, and thick forests whose floors were razor-sharp coral limestone that would shred even the inch-thick cord soles on a rifleman’s boondockers. North of Tapotchau rose four hiccups of land the Marines called the Pimple Hills.

.jpg) It took 1st Battalion three days to cover the three miles to Tapotchau’s foot-hills. The first day, Sergeant Rachitsky was shot dead. Each night, Borta had a different foxhole partner: One was a cook so hungry he went snuffling around for food, risking a bullet from another Marine to bring back the prize of a five-gallon can of fruit salad; he and Borta gobbled it until they vomited. Another chain-smoked all night beneath his poncho, coughing the whole time. The third guy slept through his watch, even when a Japanese soldier jumped into the hole. Borta snapped awake, Ka-Bar knife in hand. When he felt blade enter belly, he ripped up and back. The attacker went slack and in one motion Borta tossed him out of the foxhole. The other Marine never stirred.

It took 1st Battalion three days to cover the three miles to Tapotchau’s foot-hills. The first day, Sergeant Rachitsky was shot dead. Each night, Borta had a different foxhole partner: One was a cook so hungry he went snuffling around for food, risking a bullet from another Marine to bring back the prize of a five-gallon can of fruit salad; he and Borta gobbled it until they vomited. Another chain-smoked all night beneath his poncho, coughing the whole time. The third guy slept through his watch, even when a Japanese soldier jumped into the hole. Borta snapped awake, Ka-Bar knife in hand. When he felt blade enter belly, he ripped up and back. The attacker went slack and in one motion Borta tossed him out of the foxhole. The other Marine never stirred.

A frustrated Holland Smith knew what was up. “The Japs are being smart,” the general told a newsman. “They are fighting a delaying action, and killing as many of us as possible.” The Japanese hoped to win by attrition or to hold out until reinforcements arrived from the home islands. On a good day, the Marines only lost 10 percent of their men. On a bad day, losses went up to 15 or 20 percent. Replacements died without anyone learning their names. With the battle dragging, Smith needed fighting men. He had landed his reserve, the army’s 27th Infantry Division, and committed its men to trouble spots. He had even broken with tradition and, for the first time in U.S. Marine Corps history, ordered black Marines into battle (see “Pride and Prejudice”).

One day Borta and a BAR man from C Company came upon an abandoned Japanese field howitzer. Borta thought of throwing a grenade in the barrel but didn’t, figuring engineers would disable the gun. That night, 1st Battalion took a direct artillery hit—from the rear. Thinking they were under friendly fire, the men shot green flares to indicate that short rounds were landing on Americans. But the ground and treetop bursts continued. Shrapnel hit Borta, but most of its energy was spent so it was only like being shot with a BB gun. More rounds landed. Cries of “corpsman!” came from every corner. Borta realized this was not friendly fire: the Japanese were putting the howitzer to use. That night, C Company’s worst on Saipan, cost the unit more than 40 men.

Despite the pounding, at 7:30 a.m. on June 25, with Tapotchau looming, the American force shoved off again. The plan was to approach the mountain’s crest via two routes: the 8th Marines would drive along a ridgeline on the right flank, and the Bastard Battalion, under Colonel Rathvon Tompkins, would attack frontally through the wooded valley.

To Borta’s surprise, except for a few men shot by snipers from the rocks, 1st Battalion got through the valley with minimal enemy fire. At the end of the woods, he and Pluto Brem hesitated. To get back under cover they would have to cross a meadow.

Brem volunteered to go first. When he did, a heavy machine gun opened up. Brem zigzagged, throwing himself flat. Bullets kicked up dirt behind him. Borta returned fire into the hills, buying Brem time to crawl. The enemy gunner let loose, scattering dirt and stones. “I can’t see!” Brem yelled. “I can’t see!”

Borta sprinted across the open ground, cutting first one way and then another. He expected a hail of bullets, but the gunner kept silent. Reaching Brem, Borta discovered a second wounded Marine. He hoisted the man onto his back. Brem blindly waved a hand; Borta guided the fingers to his web belt and told Brem to take hold and get on his feet. Nearly buckling under the wounded man, with Brem clutching his belt, Borta spent what felt like an eternity returning to the tree line. He rolled the inert Marine to the ground and called for a corpsman. Taking Brem by the elbow, he sat him down. Brem flushed his eyes with hydration mixture and blinked. He could see after all, though he was not fit for combat. A corpsman came; Brem told Borta goodbye.

The 1st Battalion had run smack into the Japanese mountain defense force. By 10 a.m., Colonel Tompkins could see that progress would have a higher price than he wanted to pay. He had already lost half his battalion to injury and death.

The 8th Marine Regiment’s 2nd Battalion was having an easier go. By 9:30 its men had climbed to the base of a 50-foot cliff below Tapotchau’s crest. Skirting the rock face, the Marines moved slowly, fearing the crack! of an Arisaka or a killing burst from a Model 92, but no one fired.

Stalled in the valley at the front of the mountain, Colonel Tompkins called on a platoon from the 2nd Division Reconnais-sance Company. Using the path the 8th Marines had taken, Tompkins and the recon platoon inched to the top, where they discovered a platoon from the 8th Marines dug in on Tapotchau’s right shoulder. No one had explored the peak, so Tompkins and the recon men climbed the final 50 feet. They found a flat empty area, perhaps 30 feet in diameter. Here, on the peak’s west edge, the Japanese had dug a long trench across the mountaintop and then inexplicably abandoned it.

Stalled in the valley at the front of the mountain, Colonel Tompkins called on a platoon from the 2nd Division Reconnais-sance Company. Using the path the 8th Marines had taken, Tompkins and the recon platoon inched to the top, where they discovered a platoon from the 8th Marines dug in on Tapotchau’s right shoulder. No one had explored the peak, so Tompkins and the recon men climbed the final 50 feet. They found a flat empty area, perhaps 30 feet in diameter. Here, on the peak’s west edge, the Japanese had dug a long trench across the mountaintop and then inexplicably abandoned it.

The Japanese were bound to realize they had forfeited the island’s most important observation post and return in strength. Tompkins decided to fetch men from 1st Battalion to reinforce the recon platoon. Until that happened, the recon group would have to hold the high ground.

Tompkins and an escort party headed down. Within the hour, a few Japanese rushed the trench. The Marines held their fire until the enemy raiders were right on top of them, then cut loose with carbines and semiautomatic Colt pistols. Wounded Japanese soldiers detonated grenades, killing themselves while trying to take out Americans. It was the first time many of the Marines had seen soldiers destroy themselves with their own weapons.

Below, Tompkins was moving 1st Battalion up the mountain. They encountered no resistance, but the trail was steep and the slog was slow and difficult. As the sun melted into the sea, they finally reached the top of Tapotchau.

At the mountain’s west edge, an exhausted Chick Borta was one of a hundred men who struggled to scrape out foxholes in the rocky ground. After sunset, the enemy would be back. Borta, feeling with a chill the onset of a fever, realized why the Marines had scrambled so hard to take Tapotchau. It felt like you could see all the way to Guam, 136 miles south.

Just before midnight, A Company sent up a flare that exposed a force of bare-chested Japanese, torsos painted black, creeping up the slope. Many carried only makeshift spears—poles with bayonets or knives lashed to the ends.

Cries of “banzai!” broke the stillness. Soldiers lunged at each other, screaming. Bayonets flashed. Weapons erupted point-blank. Flesh ripped. Blood splattered. Borta saw an attacker jab a Marine from behind; the American toppled over the cliff. Borta crouched, braced his M1, and set it at a 45-degree angle. If a Japanese made it into the foxhole, he would impale himself on the bayonet and Borta would gut him like a hog. Another flare went up. Bodies, mostly Japanese, lay scattered across the rocks. Borta checked his bayonet, sank down, and waited for another charge. “Marine, you die!” a Japanese voice yelled. “Tonight you die!”

Before dawn, a captain ordered Borta to find C Company and get a crate of grenades. Borta was sure he was a dead man—he knew what he would do if he heard something moving in the dark: shoot. But he scuttled foxhole to foxhole, repeating the same desperate whisper. “Borta,” he hissed. “It’s me, Borta.” By the time he found C Company, he was so choked with fear he could barely utter his request. “Any extra grenades?” Borta said. “You kidding?” a voice answered. Empty-handed, Borta retraced his steps and told the captain that C Company had no hand grenades to spare.

The Japanese did not return to Tapotchau. Their generals decided the peak was a lost cause. By morning, enemy troops were on the run to the Pimple Hills. The Bastard Battalion pursued them to Tommy’s Pimple, stormed the slope, and shot the retreating Japanese like jackrabbits.

It was nearly two weeks before Chick Borta saw Pluto Brem—on Independence Day, when headquarters pulled 1st Battalion off the line after 19 days of fighting. Looking around, Chick Borta was taken aback. Gaunt and hollow-eyed, his fellow Marines stood shuffling in place, trying to ease the searing pain of jungle rot. Brem was a scarecrow. But at least he was alive, not among the 2,949 Americans who died taking Saipan.

It was nearly two weeks before Chick Borta saw Pluto Brem—on Independence Day, when headquarters pulled 1st Battalion off the line after 19 days of fighting. Looking around, Chick Borta was taken aback. Gaunt and hollow-eyed, his fellow Marines stood shuffling in place, trying to ease the searing pain of jungle rot. Brem was a scarecrow. But at least he was alive, not among the 2,949 Americans who died taking Saipan.

The Japanese fought all the way to the end. Rather than surrender, hundreds of civilians jumped to their deaths from a cliff. Troops more often chose ritualistic self-destruction.

The evening of July 6, 1944, Lieutenant General Yoshitsugu Saito, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, and Brigadier General Keiji Igeta, the island’s ranking defenders, killed themselves. The next morning, thousands of their men, many of them scarcely armed, charged Marine positions, running ecstatically into point-blank artillery, machine gun, and rifle fire.

After the massacre, Borta, reeling with fever, joined a patrol that went into the death zone. He had to remind himself he was not hallucinating as he walked the blood-drenched ground layered in swollen bodies, watching bulldozer operators make mounds of Japanese corpses for other Marines, as worn out as he was, to douse with kerosene and burn. Years later, that was what Chick Borta would remember from Saipan: the weary, and the dead.

James Campbell is the author of a new book about the battle for Saipan, The Color of War: How One Battle Broke Japan and Another Changed America, for which he made two research trips to the Central Pacific. His previous book is The Ghost Mountain Boys: Their Epic March and the Terrifying Battle for New Guinea.