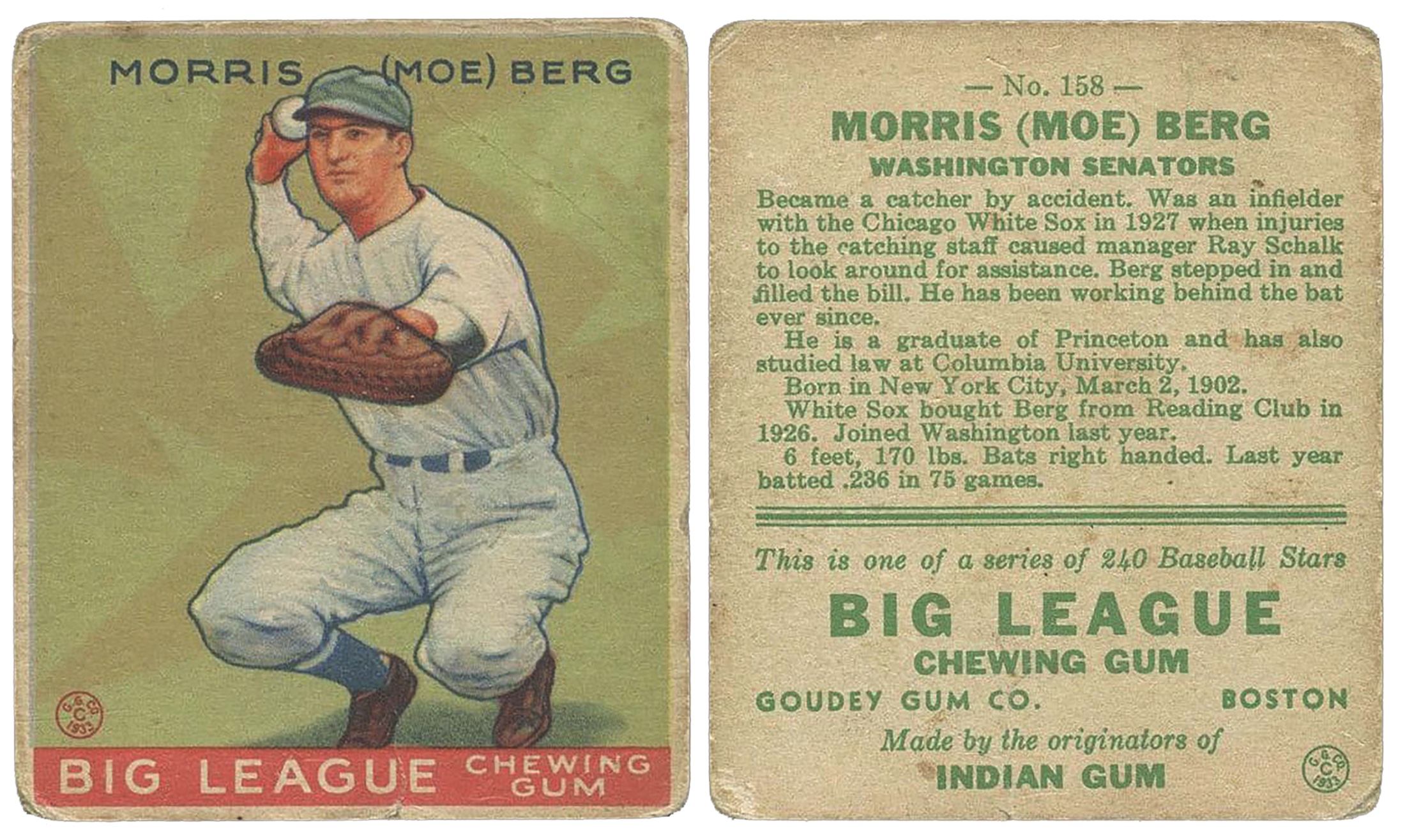

In the fall of 1934 Morris “Moe” Berg, a journeyman backup catcher for the Cleveland Indians baseball team, caught a break—or so it was thought. To the surprise of many people, he was named to a squad of 14 major league ballplayers preparing for a post-season tour of Japan, where he would be in the rarefied company of such superstars as Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmy Foxx, Lefty Gomez, and legendary manager Connie Mack. It was the first time since high school that the whip-smart but light-hitting prodigy had made an all-star team.

Why Berg was picked to join the tour in the first place was never explained. A brainy academic—he graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Princeton University, went on to earn a law degree from Columbia University, and read 10 newspapers a day—Berg was an enigma to his less intellectual fellow ballplayers, a man who was seemingly more interested in international diplomacy than daily batting averages. “He could speak 12 languages,” a former teammate once joked, “but he couldn’t hit in any of them.” It was assumed that Berg’s mastery of languages would come in handy at a time when Japan was growing increasingly hostile to other countries in the region. As it turns out, the veteran baseball player was more than a talented linguist.

He was also a spy.

No one knows exactly when Berg’s baseball career collided with his shadowy spycraft, but altogether befitting a secret agent, he was an enigma to his teammates and friends. His life, then and later, was filled with unanswered questions. Did Berg use baseball as a disguise, or did he honestly enjoy playing the sport? Those who knew him best believed it was a little of both.

The youngest of three children, Berg was born in the East Harlem neighborhood of New York City on March 2, 1902, to Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants, sharing a tenement apartment on East 121st Street with his parents and his two siblings. Berg’s father, Bernard, operated a laundry while teaching himself to read English, French, and German. From his home, Moe could look across the Harlem River to Yankee Stadium where the New York team played. In due time, he would play there himself. After excelling at night classes, the elder Berg earned enough money to open a pharmacy and move the family to a more comfortable apartment in Newark, New Jersey.

From the start, his father encouraged Berg to study and read. Although Moe thrived in school, his real passion, like many kids his age, was baseball. One day, a beat cop noticed him zipping a ball around on the street and invited him

to join the local Methodist Episcopal Church team—much to the chagrin of Berg’s hard-working father, who viewed baseball as a waste of time and intellect. The only Jew on a team of Italian Catholics and Protestants, the imaginative seven-year-old Moe created his first pseudonym, changing his playing name to “Runt Wolfe.”

At age 16, Berg graduated at the top of his class from Barringer High School in Newark and was selected as the starting third baseman for a nine-man high school “dream team” chosen by the Newark Star Eagle. In the spring of 1918, he was accepted at New York University. The following year, after two semesters playing baseball and basketball at NYU, Berg transferred to Princeton, where he played first base and shortstop. Following in his father’s footsteps, Moe studied languages, exceling in Spanish, Latin, Greek, Italian, German, and Sanskrit. When not playing ball, he tutored his teammates. He was known to confound opponents by yelling tips in Latin back and forth with equally intellectual second baseman Crossan Cooper.

Being Jewish, Berg endured some awkward moments at Princeton. When one of his teammates was nominated for membership in one of Princeton’s prestigious dining clubs, the teammate refused to join unless Berg could also become a member. The club consented on the condition that the two of them not attempt to bring any more Jews into the club. The teammates declined. Feeling responsible for his teammate’s principled refusal, Berg talked him into becoming a member anyway. As for Berg, he never returned to Princeton for class reunions.

Despite the prejudice, Berg played baseball for three years at Princeton. In his senior season, he was captain of the team, batting .337 for the year and a sparkling .611 against Princeton’s archrivals, Harvard and Yale. He played against Yale at Yankee Stadium and got three hits in one game. Graduating magna cum laude in 1923, Berg signed a $5,000 contract to play major league baseball with the Brooklyn Robins (soon to be renamed the Brooklyn Dodgers), which was eager to add a Jewish ballplayer to expand its fan base. Batting a dismal .186 as a backup shortstop that first year, Berg packed his bags after season’s end and sailed to Paris, where he enrolled at the prestigious Sorbonne to study Latin, ultimately registering for 32 classes.

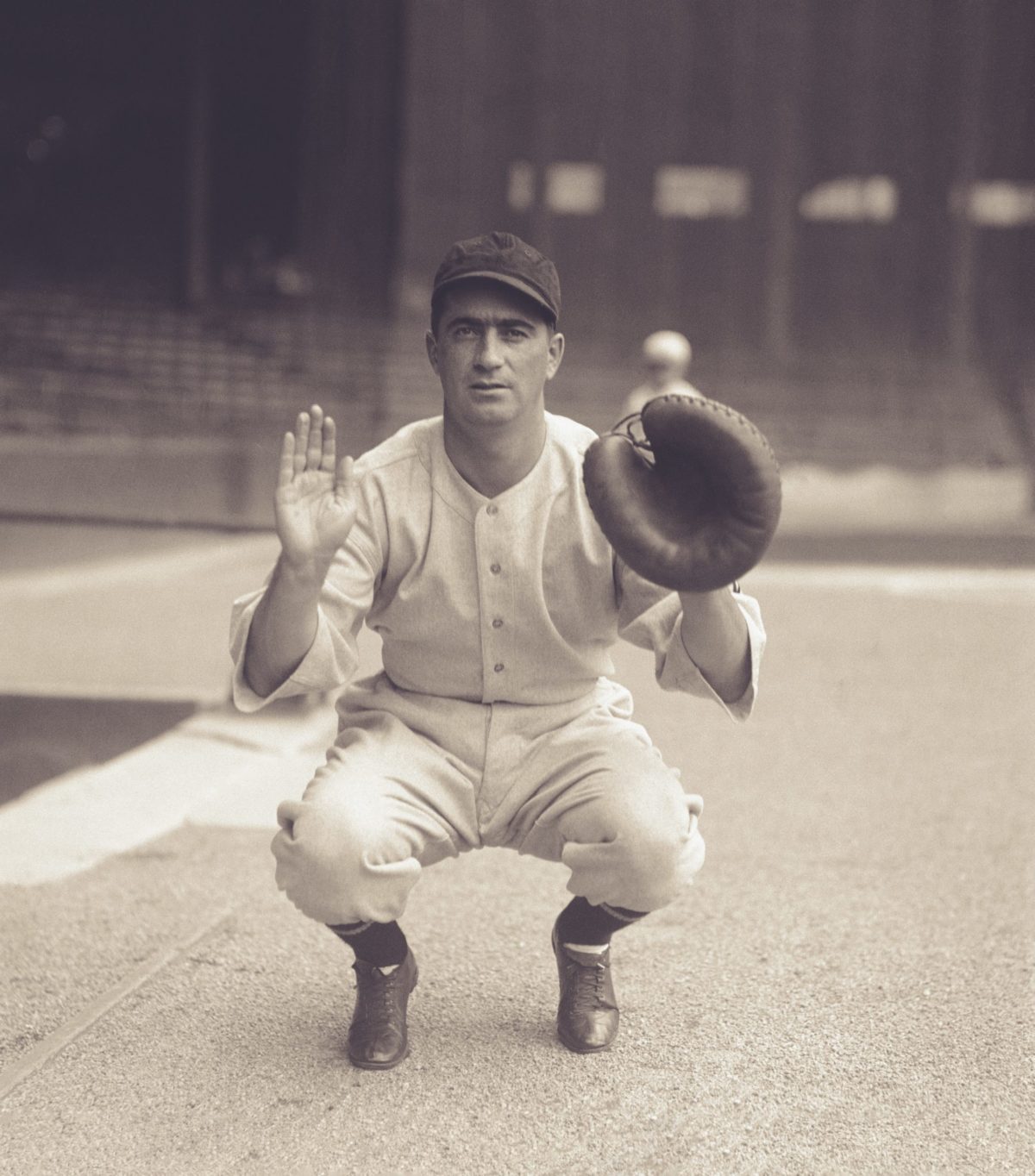

Returning in time for spring training in 1924, Berg was exiled to the minor leagues. He spent the next two years playing for the Minneapolis Millers, Toledo Mud Hens, and Reading (Pennsylvania) Keystones. His more than respectable .311 batting average with the Keystones got him a ticket back to the majors with the Chicago White Sox in 1926, but not before he skipped spring training to finish his first year at Columbia Law School. A series of injuries to White Sox catchers gave Berg an opening: He volunteered to catch, even though he had never played the position before. In his first game behind the plate, White Sox pitchers held Babe Ruth hitless and won 6–3. Berg had a found new home.

Never much of a hitter, Berg had developed a strong throwing arm and used his dominating intelligence to help his pitchers call better games. No less a player than Boston Red Sox’s Ted Williams sought his advice. During the second year of his storied career, Williams asked Berg how Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig had hit. “Gehrig would wait and wait and wait until he hit the pitch almost out of the catcher’s glove,” Berg replied. “As to Ruth, he had no weaknesses. He had a good eye and laid off pitches out of the strike zone.” The hitter Williams most resembled, said Berg, was Shoeless Joe Jackson, the former Chicago “Black Sox” great. “But you,” Berg told Williams, “are better than all of them.”

A knee injury Berg suffered in an exhibition game against the minor league Little Rock Travelers in 1929 severely limited his playing time. The following year, Berg appeared in only 20 games, hitting a woeful .115. Looking to the future, he took a job in the off-season with the respected Wall Street law firm of Satterlee and Canfield. The Cleveland Indians picked Berg up in 1931, but he played in only 10 games, managing one hit in 13 at-bats. The next spring, he joined the Washington Senators as a backup catcher, batting .236 in 75 games with no errors and throwing out 54.3 percent of would-be base stealers, the second-best percentage in the American League.

Berg’s move to the nation’s capital would change his life. He was frequently invited to embassy dinners and parties, where his quick wit and formidable language skills caught the attention of prominent members of the incoming Franklin D. Roosevelt administration. Following the 1932 season, Berg was invited to accompany fellow major leaguers Lefty O’Doul and Ted Lyons to Japan to teach baseball seminars at Japanese universities. After the other players returned to the United States, Berg made an extended tour of Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Germany before returning in time to participate in Washington’s pennant-winning season of 1933. It was a sign of things to come.

Berg returned to Japan in 1934 with a team of American League all-stars headed by Babe Ruth—Beibu Rusu to the Japanese—who had just completed his final season with the New York Yankees. Thousands of baseball-mad fans lined the streets of Tokyo to welcome the U.S. team when it arrived in November for a series of 18 exhibition games against a top-flight Japanese collegiate team.

At the time of his surprising selection to the all-star team, Berg, who by now was back with the Cleveland Indians, was known to his teammates as a mediocre player. Rumors were that his language skills had gotten him a spot on the trip as an interpreter, although at that point he spoke limited Japanese. No one suspected that his ball-playing was a guise for a top-secret government assignment. In his suitcase, he carried a letter signed by U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull, addressed to the American consulate in Tokyo and instructing the staff to show the catcher all due cooperation, official and otherwise.

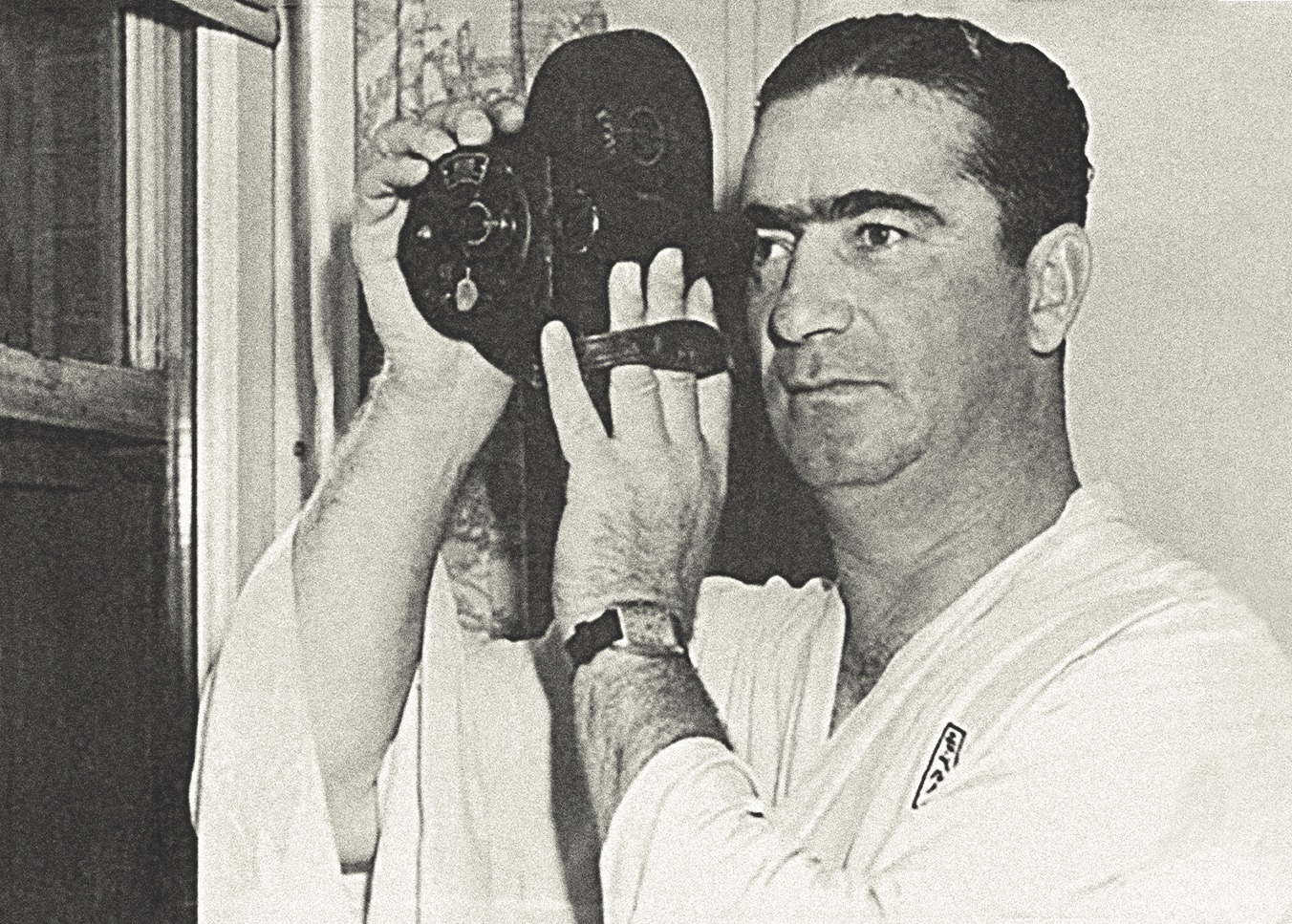

Berg played in a handful of the exhibition games in Japan—the big leaguers won all 18 and Ruth hit 13 home runs—but his real work came afterward. During his downtime, Berg would wander the streets of Tokyo in a black kimono and sandals, filming background scenes with a 16mm Bell and Howell motion picture camera provided to him by Movietone News, a newsreel production company that had contracted with him to film the trip for movie theaters back home. The Japanese government strictly prohibited such filming, but either Berg’s status as a big-league ballplayer or his disguise as a 6-foot-1 Japanese man enabled him to elude the authorities.

After a game at the Omiya fairgrounds near Tokyo, Berg slipped away, trading his uniform for his kimono, slicking back his hair, and buying a bouquet of flowers. Then he nonchalantly walked into the seven-story St. Luke’s International Hospital, one of the city’s tallest buildings. His cover story: a courtesy visit to the daughter of U.S. Ambassador Joseph Grew, Elizabeth Lyon, who had just given birth. Tossing the flowers aside once he had gained entrance, Berg sneaked out a side door to the roof. From there, with a commanding view of the city, he captured panoramic shots of the naval base at Tokyo Bay, commercial and industrial centers, and surrounding military targets. Then he quietly returned to his teammates. He never did see Lyon. His secret video was later shown to U.S. Army Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle and his raiders before their famous bombing raid on Tokyo in April 1942 in retaliation for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Following the Japanese tour, Berg continued his travels in the Far East, Russia, and Poland—all areas of great interest to American intelligence officials. After returning to the United States, he was picked up by the Boston Red Sox to resume his day job as a backup catcher. On October 17, 1938, Berg was invited to be a guest panelist on Information Please, NBC’s popular radio quiz show. Berg, who returned to the show three times, effortlessly demonstrated his wide range of knowledge by answering all types of questions, from astronomy to mythology to the derivation of words and names in Greek and Latin. “He did more for baseball in 30 minutes than I’ve done as commissioner,” Kenesaw Mountain Landis, baseball’s long-serving ruler, said. Berg also wrote a well-received article about baseball for Atlantic Monthly entitled “Pitchers and Catchers.”

After he retired from baseball in 1942 with a career batting average of .243, six home runs, and 206 RBI, Berg accepted a job with Nelson Rockefeller’s Office of Inter-American Affairs, an agency set up to counter Axis propaganda in Latin America. Berg’s linguistic talents came in handy as he met with various government officials in Brazil, Panama, and Peru. His first mission was a goodwill tour of Latin America that allowed him to covertly assess the willingness of political leaders in Latin America to side with the United States in the war.

In August 1943 Berg transferred to the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. The OSS was headed by Brigadier General William “Wild Bill” Donovan, who had commanded the 165th (formerly the “Fighting 69th”) Infantry Regiment in World War I. His recruitment was smoothed by a letter from Colonel Ellery Huntington, a partner at Berg’s law firm, Satterlee and Canfield. Berg, Huntington wrote, “would make a good operations officer, either here or on the field.” Placed on the Balkans desk at the OSS, Berg monitored the movements of the exiled Yugoslavian king, Peter II, who was now a student at Cambridge. He also received field reports and cross-checked them with members of the Slavic-American community who likewise had been recruited into the OSS. (Stories that Berg parachuted into Yugoslavia to personally meet with Chetniks and communist partisans under Josip Broz Tito are now considered apocryphal.)

In late 1943 Berg was tabbed for a highly sensitive clandestine operation behind enemy lines in Europe. His mission, as part of Project Larson, was to interview top Italian scientists to assess their knowledge of Germany’s atomic bomb program. To prepare, he met with Nobel Prize–winning physicist William Fowler and Vannevar Bush, the chief of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development. In April 1944, after he was officially named an intelligence agent in the Special Ops Branch and authorized to carry a .45-caliber pistol, Berg flew to Italy via Portugal and Algiers. Neither he nor most other Americans knew at the time that the United States was already developing its own atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert under the code name the Manhattan Project.

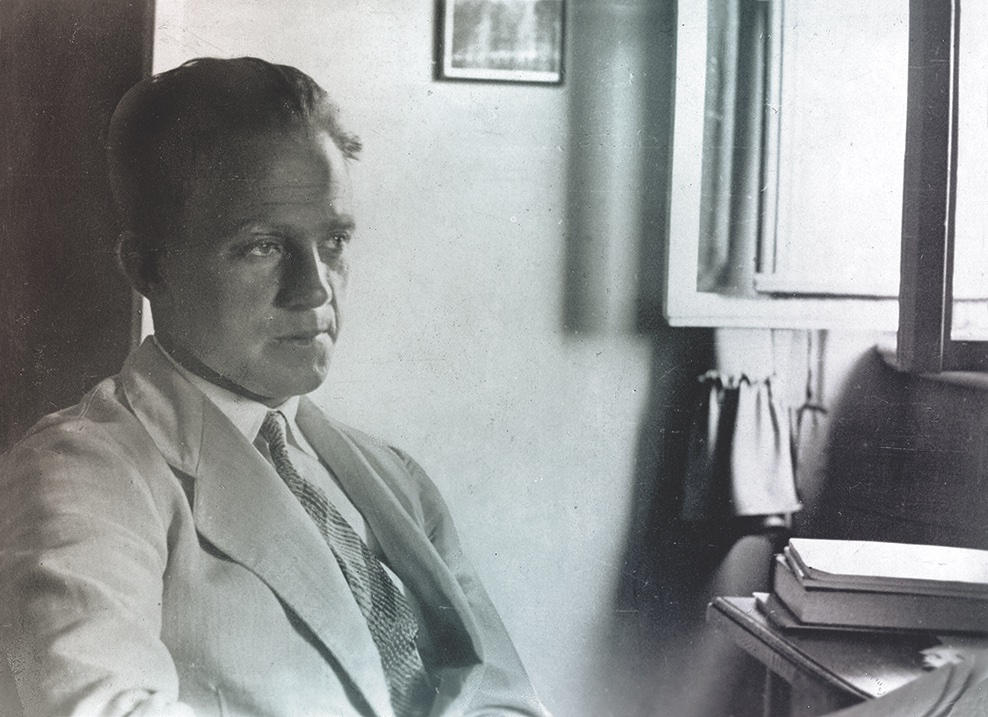

Berg entered Italy on a submarine the OSS borrowed from the Italian navy at Brindisi. After landing he went to Florence to visit the Galileo Laboratory, where Italian scientists were working on long-range missiles. From his interviews with the Italians, Berg learned that Werner Heisenberg, the preeminent German physicist in charge of the Nazis’ nascent nuclear program, was scheduled to give a lecture in Zurich. Berg made contact with Paul Scherrer, the director of the Physics Institute in Zurich, and arranged to attend the lecture posing as a Swiss graduate student. Armed with a pistol and a potassium cyanide capsule to swallow if necessary, Berg had orders to shoot Heisenberg if Berg determined from the lecture that the Germans were close to developing an atomic bomb.

The Nobel laureate was seated in the front row of the auditorium, surrounded by armed Nazi soldiers. Berg, who had a basic understanding of nuclear physics, took meticulous notes during the lecture. A bit nervous and in over his head when Heisenberg launched into a lengthy discussion of S-matrix theory, Berg nevertheless concluded that nothing Heisenberg said in the lecture justified shooting him. Berg’s snap judgment was confirmed when he attended a post-lecture dinner in Heisenberg’s honor and overheard the German remark that his country was losing the war and was nowhere near developing an atomic bomb. Heisenberg was spared the bullet and Berg the cyanide.

Staying on with the OSS until it was dissolved in 1945, Berg transferred to the staff of NATO’s Advisory Group for Aeronautical Research and Development. In 1951 he asked to be named station chief of the CIA office in Israel, but his request was denied. During the height of the Cold War, Berg was assigned to Europe to monitor the Soviet Union’s atomic program. He made it through the Czech Republic with nothing more than a scrap of paper emblazoned with a red star but ultimately learned nothing of value. The CIA officer who debriefed Berg on his return reported that the former catcher was “flaky.” Berg’s contract expired in 1954.

Financial troubles plagued Berg for the rest of his life. For 17 years he lived with his brother Samuel in Newark before Samuel finally kicked him out, leaving their sister, Ethel, to deal with the eccentric former spy. Berg became a hoarder, spending his days reading stacks of newspapers. No one was allowed to touch his papers until he had read them all. If anyone did, he considered the touched papers “dead” and would go out and buy the same ones again. He also wore the same black suit and tie every day and took three baths.

Awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Harry S. Truman in 1946 for his wartime service, Berg declined to accept when he was told that he couldn’t explain to friends how he had earned the honor. He never married or held a full-time job after his baseball career ended. Instead he led a nomadic existence, carrying only a toothbrush and craftily making friends with train conductors who would let him ride for free. He spent hours at the New York City’s major league ballparks, watching the Yankees, Dodgers, or Giants play. One night he ran into his old friend Joe DiMaggio, who offered him a night’s stay at his upscale Manhattan hotel. Berg spent six weeks living off the Yankee Clipper’s hospitality.

In 1960 Berg made plans to write a book detailing his exploits as a ballplayer-spy. The project foundered after Berg’s cowriter mistook him for Moe Howard of the Three Stooges. The book was never written. Whenever anyone asked Berg what he was working on, he would hold a finger to his lips and whisper theatrically, “Shhh.” It was the closest he came to admitting that he’d been a spy.

Berg died on May 29, 1972, at age 70 from injuries he sustained in a fall at his sister’s home. A nurse at the Newark hospital where he died recalled his final words: “How did the Mets do today?” (They won.) In keeping with his stated wishes, his cremated remains were spread over Mount Scopus in Israel.

Later that year Berg’s sister accepted the Medal of Freedom on his behalf and donated it to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, where it is displayed alongside his well-worn catcher’s mitt and passport. Berg would have approved. “Maybe I’m not in the Cooperstown Baseball Hall of Fame like many of my baseball buddies, but I’m happy,” he once said. “I had the chance to play pro ball and am especially proud of my contributions to my country. Perhaps I couldn’t hit like Babe Ruth, but I spoke more languages than he did.”

In recent years Berg’s shadowy exploits have inspired a best-selling book The Catcher Was a Spy, by Nicholas Dawidoff; a 2018 movie of the same title starring Paul Rudd; and a 2019 documentary The Spy Behind Home Plate, by Washington-based filmmaker Aviva Kempner. Berg’s major league baseball trading card is prominently displayed at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

Former major league player and manager Casey Stengel, himself a noted eccentric, succinctly summed up Moe Berg. Stengel, like Berg, played for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and once doffed his cap to let a bird fly out. In later years, as manager of the New York Yankees and New York Mets, he was celebrated for “Stengelese,” his fractured use of the English language. Berg, said Stengel, was “the strangest man ever to play baseball.” He would have known. MHQ

Liesl Bradner, a California-based journalist, is the author of Snapdragon: The World War II Exploits of Darby’s Ranger and Combat Photographer Phil Stern (Osprey Publishing, 2018).

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2020 issue (Vol. 33, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Baseball’s Odd Man Out

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!