On terrain that favored riflemen, rough-hewn American general routed overconfident British regulars

[divider]On a bone-chilling morning in January 1781, British forces led by Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton confronted Continental Army troops commanded by Brigadier General Daniel Morgan at Cowpens, South Carolina. The face-off came at a crucial juncture. The preceding May, Charleston, the Americans’ most important port in the South, had fallen to the British. Taking 5,500 prisoners and their artillery and supplies, imperial forces now stood to dominate the region. Frantic, Congress dispatched General Horatio Gates, the “Hero of Saratoga,” to lead the scant American forces remaining in the Southern theater of operations. Leaving for the Carolinas in June, Gates paused in Winchester, Virginia, to entreat Colonel Daniel Morgan to join him in the south.

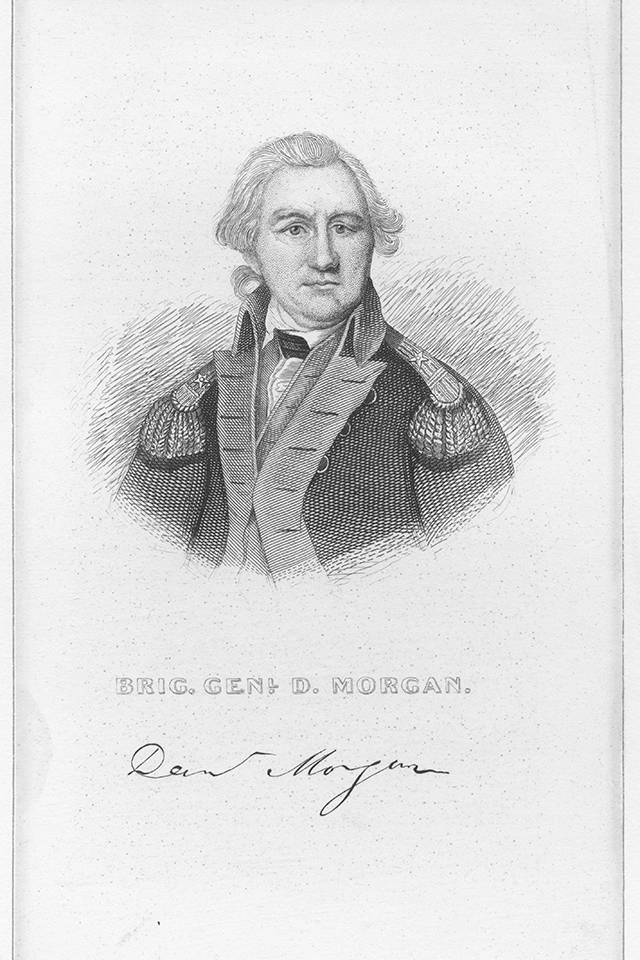

[divider_flat]Morgan, 44, a tough, semiliterate frontiersman and wagoner, had a long history of wilderness fighting. In 1763, he had been with Braddock’s doomed force at Fort Duquesne—a march on which, for striking a superior, he was lashed, cementing a profound hatred on his part for the British. At Saratoga in 1777 Morgan, with Benedict Arnold, had led the attacks that defeated the British, and outside New York City in 1777 he had handled Washington’s rangers with ingenuity and skill. Now Morgan was back home in Winchester, retired from military service and nursing his war-weary back and legs. Gates offered Morgan command of a light corps, and Morgan accepted, provided Gates petitioned Congress to have him promoted to the rank of brigadier general; Morgan felt he otherwise would lack the status to compete with higher-ranking militia commanders in the southern theater. Gates agreed to present the petition, and did so.

In August, with Morgan still mending in Virginia, Gates was on the road to Camden, South Carolina, when he marched his command literally headfirst into Cornwallis’s army. The sight of British bayonets was enough to rout the militiamen who made up two-thirds of Gates’s force, and Camden became for the Americans another humiliating defeat. In September, Gates and his battered army were camped at Hillsborough, North Carolina, when Morgan appeared, recovered from his nagging condition. Morgan received his commission as brigadier general on October 25, to the delight of his new command.

In October, Congress replaced Gates with General Nathanael Greene, a favorite of George Washington and a strong strategic thinker. Greene and Morgan had become acquainted during the siege of Boston in 1775, when Washington had looked favorably upon both. Their careers had diverged—Greene was quartermaster general, while Morgan excelled at leading light troops in the field—but the two men had great respect for one another. Greene saw the American position in the South—a small, beleaguered force versus Cornwallis’s significantly larger complement—as untenable. To compensate, Greene chose a bold gambit. He would divide his army, moving with the main body to Cheraw on the Pee Dee River in South Carolina. At the same time Morgan would lead a force composed of the Delaware and Maryland Continentals, a veteran regiment of Virginia militia, and a small contingent of dragoons under Colonel William Washington into the wilds of South Carolina and establish a camp on the Pacolet River 148 miles from Cheraw. Greene meant to present Cornwallis with an unsavory choice: to move against either American force would free the other to do mischief behind the British leader’s back.

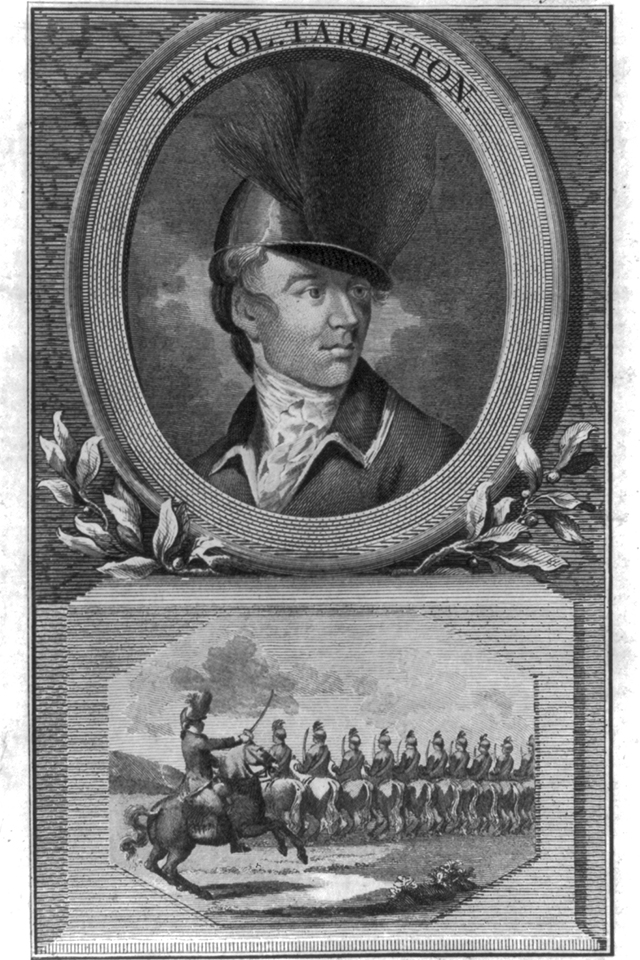

Greene’s plan eroded when Cornwallis got reinforcements sufficient to let him pin down one rebel contingent and move against the other. Cornwallis chose to attack Morgan’s camp with Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton in command of a 1,100-man force of dragoons, infantry, and artillery. Tarleton, a tough, relentless cavalryman, was a pet of Cornwallis, who relied on the younger man to project British strength at distance. A measure of the general’s regard appeared in a note he wrote in December 1780. “I wish you would get three legions, and divide yourself into three parts,” Cornwallis told Tarleton. “We can do no good without you.” Tarleton had a reputation for barbarity. His victory at Monck’s Corner included ruthless murder and accusations of rapine. At Waxhaw, his troops butchered Continentals who had surrendered. North of Charleston, men of Tarleton’s Legion savaged civilians, plundering and burning homes. “Monck’s Corner revealed Tarleton’s darker side, which was never distant,” writes historian John Buchanan. “It is not unfair to state that in time and with reason he became the most hated man in the South.”

In early January 1781, Tarleton’s Legion went after Morgan, splashing across the Enoree River. Alerted by his scouts, Morgan, who had as many men as Tarleton, withdrew north as the Legion was crossing the Pacolet. Searching for suitable ground on which to offer battle, Morgan, following winding, sandy Green River Road, came upon an open meadow to which locals brought farm animals for branding. Green River Road, the winding, sandy path upon which Morgan’s column had arrived, bisected the meadow, which cattlemen called the Cowpens. The Cowpens, dotted with oak, pine, maple, and hickory trees, sloped gently north for about 450 yards. A swale and a minor ridgeline snaked across the meadow, which rose to a slight crest, dipping and rising further to another crest before dropping off toward Broad River, some six miles north. The ground would do little to inhibit attacking infantry and dragoons, but did offer areas where troops might conceal themselves.

By the numbers, Morgan and Tarleton were evenly matched. However, many of Morgan’s men were recently arrived frontier militiamen, good with a long rifle and hunting knife but untrained in battlefield discipline. Their general, recalling how at Camden American militia had fled British bayonets, and assuming Tarleton’s professionals were likely to charge hell-bent for leather, sabers and bayonets out and artillery in support, realized he had to help his men stand fast despite their inexperience.

Morgan deployed three lines of riflemen, approximately 150 yards apart. In the first he placed his best marksmen, with orders to pepper the foe with two or three volleys, then withdraw behind the second American line. That second line, partially hidden by the first crest, consisted of militia riflemen. These men also were to fire two or three volleys before falling back behind the main and third line, concealed from British view behind the second crest. Joining that final line of bayonet-wielding Continentals and veteran Virginians, the surviving force would make its stand. Continental bayonets would shield the militiamen while they added their long rifles to the Continentals’ musketry.

Early on January 17, 1781, Tarleton’s Legion, hungry and exhausted from a pre-dawn march, appeared on the Green River Road at the foot of the Cowpens meadow, and with characteristic flamboyance immediately undertook an assault. “The enemy came in full view,” militiaman James Collin wrote later of the experience, which occurred in his adolescence. “The sight, to me at least, seemed somewhat imposing.”

Without properly reconnoitering enemy positions or deploying troops per standard practice, Tarleton—likely assuming he was seeing a weak rearguard that a foe had posted hoping to facilitate his escape—ordered his command into line of battle and set his men running and galloping. None knew he was advancing upon two lines of heavy infantry, unseen, undetected, and waiting with muskets primed and ready.

Each in turn, the first American skirmish line and then the secondary militia line savaged the advancing British, in sequence falling back to the position the Continentals and Virginians were defending. The sides were fighting furiously there when Tarleton tried to turn the American right flank. Spotting this gambit, Lieutenant Colonel John Eager Howard, commanding from his horse behind the American line, ordered his endmost infantry unit to face the enemy. Howard’s men misunderstood his shouted command. Instead of facing left to engage the foe, those at line’s end about-faced and began to withdraw, emulated quickly in error by the entire American line, to Howard’s dismay. The Redcoats, presuming the rebels to be in retreat, pressed forward wildly.

Morgan and Howard improvised. Morgan galloped uphill about 100 yards from the British flanking movement to a point where he wanted the American line to halt. Howard rejoined his command and led the American infantry to where Morgan waited. As the withdrawing Americans were approaching Morgan’s new position, Howard ordered his experienced troops to stop and turn to face the attacking foe, only yards behind. The Continentals, trained to reload while withdrawing, had their muskets primed. At Howard’s order, the men wheeled and loosed a volley point-blank into the advancing British faces. Staggered, Redcoats not cut down fell to their knees or stumbled back.

Grasping the moment, Howard screamed, “Charge bayonets!” Continentals surged into, through, and over the stunned enemy. At the Continentals’ flanks, militiamen joined the attack. Washington’s cavalry circled the fleeing Britons, who within moments were enveloped and undone or chased for miles by pursuing Americans. The battle had lasted about an hour.

Hardly a British infantryman escaped injury, death, or capture. Tarleton fled with some dragoons, but of the Legion’s 1,100, 810 had fallen or been taken prisoner. In a blink, Cornwallis had lost a quarter of his army’s strength. “The enemy were entirely routed, and the pursuit continued upwards of twenty miles,” Morgan reported to Greene. “Our loss was inconsiderable, not having more than twelve killed and sixty wounded.” A fuming Cornwallis, bent on retrieving his captured soldiers, attempted for days to maneuver Morgan into battle at Ramsour’s Mill in North Carolina, 60 miles northeast. However, Morgan, out-marching Cornwallis, put too much distance between his column and his would-be pursuer for the British to catch him. So frenzied did the Briton’s pursuit become that he sent his army on a punishing march that carried his troops to battle at Guilford Court House, North Carolina, and then to Yorktown, Virginia. The rest is history.

Morgan’s victory at Cowpens, according to General Sir Henry Clinton, then commanding British forces in America, was “the first link of a chain of events that followed each other in regular succession until they at last ended in the total loss of America.”