On Aug. 22, 1945, a Miles Messenger aircraft carrying British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery dropped abruptly from the sky near Oldenburg, Germany as its engine cut out in midair. The plane had no chance of making it to the nearby airfield. It barely managed a crash landing. The pilot and a staff officer traveling in the plane were unharmed. Montgomery’s condition, however, was much more serious. Battered and bruised from the landing, he had also sustained two broken lumbar vertebrae.

The excruciating pain of a broken back would have been enough to make anyone yell and curse aloud, stop for rest or demand immediate medical treatment—or probably all those things at once. But Montgomery’s thoughts were with the men of the 3rd Canadian Division, who were assembled and waiting for him to present valor medals and address them. He pulled himself together. As he had done so many times before, he buried his sense of self, put on a brave face as the indefatigable “Monty” and went to go see the troops.

Montgomery was an extraordinarily self-disciplined man, but this quietly agonizing struggle at Oldenburg was one of his most amazing feats of self-control. With a fractured spine, he walked along as he normally would to review the Canadian troops. The lower back injuries he had just sustained would be life-changing and cause him problems for many years; in fact, he would never completely recover. Yet despite the suffering he must have felt walking, Montgomery managed to appear unflinchingly calm as he regarded these men, who had fought for him across Europe, including at the D-Day landings, at Caen, and the Battle of the Scheldt. Footage from the event shows him–albeit slowly, probably in acute physical pain–stepping forward to present a medal to each recipient. He spoke considerately to each man as he pinned their medals on, showing only the faintest trace of a wince.

And he would have done more for them. He certainly tried. Montgomery was accustomed to make rousing speeches to troops he visited. The Canadians would get nothing less from him—or at least that was what he intended. Monty made his best effort at a speech to the officers, but shortly after he raised his voice to hail their achievements, his crash injuries finally got the best of him. He was forced to break off his speech and return to his headquarters—by plane, as he admitted he could not endure a long bumpy car journey.

That Aug. 22 has not gone down as a day of distinction compared with anniversaries of Montgomery’s major battles in the annals of World War II history. However, the private battle Montgomery waged with himself that day was one of the finest examples of what made him a great military leader.

A Global Military Leader

Montgomery’s critics have accused him of being self-serving and incompetent. They have typecast him as a timid, deskbound type of general who was persistently “frightened” of the enemy. Any military successes he made they minimize or attribute to others; any perceived failings or missteps they magnify out of proportion. Not content to assassinate his character as a soldier, his detractors have lampooned his short stature and sharp facial features, his accent, mannerisms, and practically anything else about him they could possibly think of over the course of decades. Montgomery has been savaged on both sides of the pond by an assortment of supercilious British writers and American commentators with a U.S.-biased axe to grind. When Montgomery died in March 1976, The New York Times published an obituary for him. They need not have bothered calling it an obituary. It was an attack on Montgomery: a derogatory satire that danced on his grave, containing inaccuracies and barbs unbecoming of a tribute to a deceased war hero and certainly unbecoming to one who had led all Allied ground forces, including Americans, on D-Day. Yet that is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of misrepresentations of Montgomery.

Montgomery’s actions as a military leader tell a different story—that of an earnest and hardworking officer who subordinated his own interests to his sense of duty and discipline. His approach to leadership in war demonstrates that his rise to high command was built on real talent that he honed over a lifetime of dedication to his profession. Montgomery was not born into privilege nor did he enjoy any advantages in his career that sped him to the top.

It was by the merits of his deeds that Montgomery rose through the ranks and led armies to victories in battle. The troops he led to victory came from a variety of nations, making Montgomery a truly global military leader. The achievements he made were unprecedented and have not been equaled since.

The man scorned as “timid” by some military contemporaries and a variety of historians was in fact distinguished for his great physical courage and charisma from an early age. Like many of history’s notable military commanders, Montgomery was indeed short and wiry, yet at the same time was a force to be reckoned with. As a young man, he was an aggressive and successful athlete who excelled at a wide variety of sports. He became a notorious scrapper during his time at the Royal Military College Sandhurst and was nearly expelled for rowdy brawling. As a junior officer he won awards for his skills at bayonet drills and marksmanship. He was first recognized for valor in combat with the Distinguished Service Order (DSO), which he earned for leading his men in hand-to-hand fighting in the trenches of World War I. Montgomery’s “conspicuous gallant leading” came early in the war—practically as soon as he could come to grips with an enemy force. On Oct. 13, 1914, then Lt. Montgomery rallied his men to storm German trenches with fixed bayonets, killing enemies and driving them out.

After routing the enemy, Montgomery was shot by a sniper. The bullet pierced his lung. He fell in the open. A man of his platoon came to help him and managed to plug Montgomery’s wound to stop the bleeding. However, the enemy sniper watching was not finished. The German shot Monty’s rescuer through the head, then continued to aim at Montgomery after the body fell on him. Stuck beneath the body of the man who had saved his life, Montgomery felt the corpse jolt as it took several more bullets intended for him. The German sniper was determined to kill him. Another shot hit Monty in the knee. Yet he survived. His wound was by all accounts judged fatal and his condition was bleak. After he was taken by stretcher bearers to an advanced dressing station, a grave was dug for him. Physicians thought he was a lost cause and prepared for his imminent burial.

As if defying the laws of nature, Montgomery clung to life. Evacuated to England for surgery and more advanced medical care, he made a full recovery—enough to go back to doing the military exercises he loved and engage in sports such as football and cross-country skiing. However, Montgomery by his own description was left with “half a tummy and one lung,” which caused him to get winded more easily and gave him trouble tolerating cigarette smoke around him. Some critics have treated Monty’s antipathy toward cigarette smoke as him being unnecessarily fussy. That is not the case. Inhaling cigarette smoke was actually a serious health issue for Montgomery. However, he did not form an anti-smoking attitude per say and enjoyed distributing cigarettes to his troops.

The Best Warrior He Could Be

Extremely intelligent and methodical, Montgomery set out to study everything he could about warfare and gain as much experience as possible in a variety of military roles. This flexibility and attention to detail served him well. While Montgomery is often portrayed as a misfit for his single-minded attention to his career, he showed dedication that is truly admirable for a professional soldier. His quest to immerse himself in his work was born of fierce determination to become the best warrior he could be.

Most of history’s successful military leaders are those who pursue a spartan lifestyle and accustom themselves to discomforts and deprivations. Likewise, it was typical of Montgomery to seek no extra luxuries for himself. Throughout his life, he lived and worked among his troops. In his spare time during World War II, he visited factories to encourage civilian workers on the home front. He took short rest periods when he needed to and then got back to work. He was constantly active and seeking to make himself useful.

Montgomery has often been mistaken for a Christian Puritan of sorts, an assumption not helped by the fact that he was brought up in an ecclesiastical family (his father was a bishop) and that he was known to quote the Bible during World War II. Yet Montgomery was no saint—and he knew it. He was a soldier’s soldier, who had become one precisely by rejecting the morose Christianity of his upbringing and going against the wishes of his family. He went to music halls as a young man; he bantered, took bets and swore; he sported tattoos and condoned prostitution. He wasn’t against his fellow soldiers indulging their vices, and many times was amused by their repartee about their exploits. But he demanded more from himself to reach his own aims.

“If you can’t command and control yourself, conquer yourself, you won’t be able to do this to other people,” he later said. “That’s the first thing I learned.”

Although Montgomery identified as a Christian, his views were often out of line with what the Church of England considered appropriate. He had a deep sense of faith, but it was a faith he practiced independently. His very public displays of religious piety and Bible quoting diminished in large part after World War II was won, indicating that he had emphasized these things in wartime for the sake of inspiring his men.

Motivating His Troops

One of the keys to Montgomery’s success as a military leader was his ability to motivate his troops. This sounds fairly simple to the uninitiated but takes talent to do. It’s not enough to win over a group of battle-hardened and cynical soldiers by showing up with a smile and making a speech. Soldiers are good judges of character and are not easily charmed by any new CO who comes on the scene. The loyalty of troops must be earned—and earning their respect and allegiance can be difficult, especially when the troops in question have endured immense hardships and losses. This was something that Montgomery understood well.

Because of his own experiences on the frontlines, he knew what it took to motivate men to fight. A winning strategy was not enough. The troops needed to be welded, willingly, into an energetic and effective “fighting machine,” as Monty liked to call it. To do so, Montgomery focused on building the men’s morale. “Morale is a mental rather than a physical quality, a determination to overcome obstacles, and instinct driving a man forward against his own desires,” according to Montgomery, who also wrote that morale consisted of “discipline, self-respect and confidence,” among other qualities. Morale was something he focused a great deal on and which paid dividends in terms of the effect its boost had on forces under his command.

Taking On Rommel

Perhaps the most dramatic example of the transformative effect of Montgomery’s leadership on a military force occurred when he took command of the British Eighth Army in North Africa in 1942 following its series of defeats by German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. The British had effectively been chased around in circles in the desert by Rommel to the point that the men were in awe of Rommel while making jokes about their own seemingly futile situation. Montgomery had no patience for it.

Although he was the first to appreciate the ironic humor of fellow British soldiers, he found the general atmosphere of stoic resignation to the nearby German menace unacceptable. After taking command, Montgomery electrified the Eighth Army with his hard-hitting and dynamic presence. Begrimed men who had been shuffling despondently through the desert were suddenly dashing around in a state of high alert, exercising constantly, and being told they were going to “hit Rommel for six” right out of Africa—which they did, true to their new commander’s word and thanks to his good leadership.

Talent at improving morale is not the sum total of Montgomery, although it’s possibly the only thing that faultfinders grudgingly give him credit for. He proved his abilities at organization in managing his staff and was good at delegating tasks to others—skills that other forceful personalities in military history have lacked.

A Gifted Communicator

He was also a gifted communicator. Some detractors have criticized his forthright manner and at times blunt style of speaking; some have even gone so far as to suggest he had a developmental disorder which stunted his social abilities. This is not only an unkind suggestion but one that is patently false in view of Montgomery’s behavior and achievements. Montgomery was a highly effective communicator with a great deal of international experience. He spoke several different languages—Urdu, Hindustani and French—and had lived and worked among people of various nationalities in many different countries around the globe by the time World War II started. He worked deftly with his staff and junior commanders. He established a network of liaison officers to report back to him about what was going on among various units so that he could keep his “finger on the pulse” of his troops.

He was well-organized, confident and concise—traits that can be found in many successful high-level executives as well as in efficient military leaders. Not everybody appreciated Montgomery’s conciseness or self-assurance. Like most soldiers, Montgomery could be sharp and gruff sometimes. However, he maintained a professional demeanor. He did not heckle or make abusive jokes about other Allied generals, even when he strongly disagreed with them. He treated his contemporaries with respect—which is more than some of them gave him.

Positive Command Style

Montgomery was a tough man and formidable commander, but his approach to generalship wasn’t one of boot-stomping bravado. During World War II, a time period when various strongmen were aiming famous frowns and jaw-jutting glares at each other across the globe, Montgomery was the cheerful general. He smiled in most of his pictures and liked to be photographed appearing casual and friendly. If he had been more willing to scowl for the cameras or had posed brandishing a pair of pistols he might have had to endure less derision than posterity has accorded him. But scowling and saber-rattling were not part of Montgomery’s style.

Monty was a man who knew his own strengths and didn’t need to put on a show of them. Instead, he believed in leadership that brought out what was “positive and constructive” in other people. The soldiers and civilians of war-torn Britain had endured much hardship with grim fortitude, and Montgomery sought to uplift their spirits. His goal was to brighten their horizon and encourage them to believe in victory.

In a testament to his fair-mindedness, Montgomery would also attempt to wield a positive influence over the German civilians he oversaw in the British Zone of occupied Germany, writing in a 1945 address to them: “I will help you to eradicate idleness, boredom and fear of the future. Instead, I want to give you an objective, and hope for the future.”

Imbued with a profound desire to preserve human life whenever possible, he was careful and meticulous in how he deployed his forces. Much is said of Montgomery’s ego, yet had he been more of a show-off and less of a strategist, he would have been more careless with his men’s lives. Although military history enthusiasts may find Montgomery’s methods less glamorous than those of other World War II commanders, the thoughtful approaches he utilized during that war are a testament to his sense of personal responsibility for the lives entrusted to him. “Success is vital,” he wrote, “but battles must be won with the least possible loss of life.”

He was true to those words. Being a butcher or a gambler on the battlefield is something he could never be accused of. He also routinely took measures to relieve his fatigued combat troops with fresh (but well-trained and appropriately chosen) reserves to avoid over-exhausting them. It was not always possible to replenish his manpower but he used opportunities as they came up; he did not leave troops in the lurch nor use them as cannon fodder.

Visiting U.S. Troops

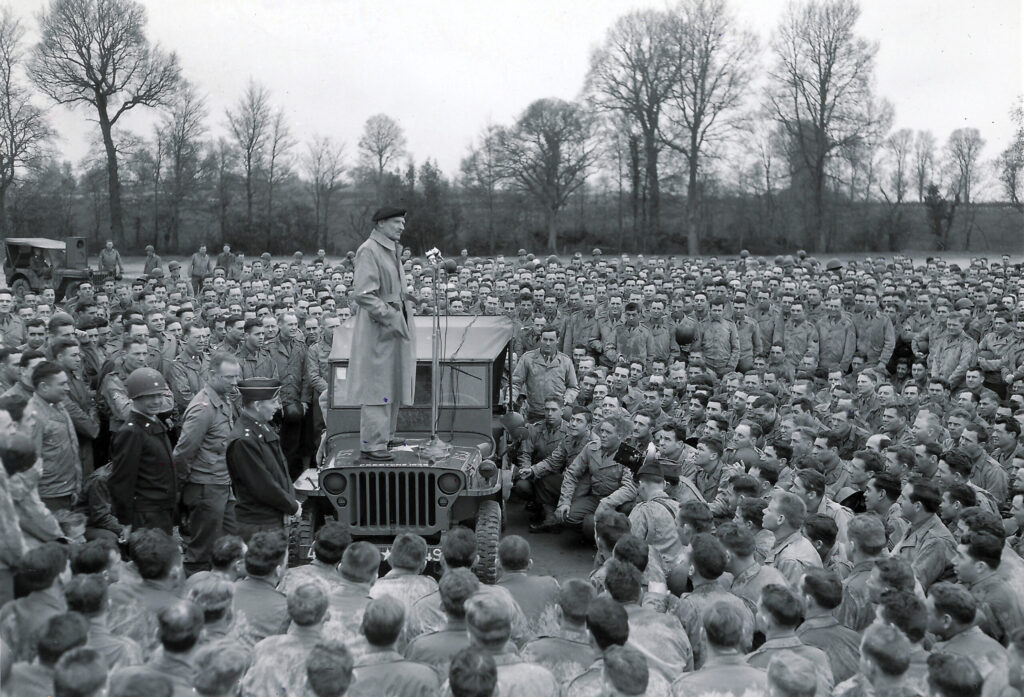

In response to his genuine concern for their wellbeing—which he manifested by constantly mingling with the regular soldiers and keeping attuned to their circumstances–Montgomery’s troops formed a close bond with him which was evident in battles across North Africa, Italy and Northwest Europe. Although Montgomery has often been accused of British bias and being indifferent to the concerns of Americans, he visited U.S. wounded in hospitals and made a point of personally introducing himself to every American combat unit he would command during the D-Day invasion.

There was not a single U.S. soldier who hit the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944 who had not set eyes on Montgomery in person and heard his voice. Montgomery wanted all soldiers he was entrusted to lead into combat to know that he took personal responsibility for them, regardless of nationality.

He was deeply affected by the sacrifices made by all Allied troops in World War II, and despite what some may claim, did not view himself as deserving of personal praise for what he viewed as their victories. His profound feelings of humility in this regard are perhaps best expressed in an address he made to officers from the 51st Highland Division after World War II. “I have never had an opportunity of saying this: during the course of the war it has fallen to my lot to receive from the nations taking part the highest decorations and orders that they can give, and when one wears them, one feels that they were really won by the officers and men,” said Montgomery. “They won them. I may wear them…but you, gentlemen, won them; and I say that straight from the heart.”

He was reluctant to admit that he had received a hero’s welcome in postwar visits to Australia and New Zealand, instead writing in his memoirs: “I knew that the warmth of the greeting was not meant for me personally but for that which I represented…the bravery and devotion to duty of the men I had commanded.”

Putting Himself Last

Partially as a result of Montgomery’s optimistic approach to wartime publicity, people got to know him as the grinning, peppery character in the beret. He was good at putting on a bold face and meeting the needs of others, even if he was personally exhausted—or had a broken back. There was much more to him than what came across in the various publicity stills and speeches. Montgomery had a quiet sense of dignity.

True to his ethos of putting duty first and himself last, Montgomery was probably the only Western Allied general who became a homeless veteran after the war. His home and belongings in Portsmouth had been destroyed by Luftwaffe bombing. During the war, he lived in caravans captured from German and Italian forces in Africa—one truck was his sleeping quarters and one was his office. Otherwise, he had nowhere to live. And it is telling that he made no effort to address that situation throughout the conflict. He made no attempt to secure a safe place to live while on leave or purchase any kind of home for himself. He worked. He fought. He was with his troops 100 percent. When he returned to Britain after the war, he lived in his trucks parked at a friend’s property for a period. He ended up purchasing an old mill to renovate as a home, which he furnished with donated materials he received from New Zealand, Canada and Australia, as the British government made minimal efforts to assist him in transitioning into postwar life.

A Life Of Service

Although he had every right to retire after the war ended, Montgomery continued to dedicate himself to a life of public service. Even during the war he had been an active mentor to junior officers and had been involved in charity efforts. He accumulated an unbroken 50 years (1908-1958) of active military service before retiring. Even afterwards, he continued to be productive in monitoring international and military affairs, and writing books to make his analyses and experiences of use to others. “Individual happiness, cheerful loyal service, giving a helping hand to others, gaining the trust and confidence of those you deal with—it is those things that matter most, to mention only a few,” he wrote.

In a 1953 photograph taken around the time of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, Montgomery appears at the pinnacle of his career, wearing the hallowed robes of the Order of the Garter. Pinned discreetly at the front of his robes—slightly askew and against dress regulations—is a lone valor medal. It is his DSO: the first award he received for his bravery on Oct. 13, 1914, the day he barely escaped a sniper’s malice and was left struggling for life on a deserted battlefield. So many years later, he was alive, well and surrounded by magnificence. But one thing had not changed. He was still that same ordinary soldier. He knew it.