Profiteers on both sides of the war lined their own pockets at their countries’ expense

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Civil War typically evokes images of daring soldiers in blue and gray whose fortitude and self-sacrifice on the battlefield drew the respect and wonder of equally patriotic citizens, all willing to endure home front hardships in order to win the war. Yet for a self-serving group of officials, manufacturers, and other profiteers, the war was a chance to advance their own interests at the expense of their countrymen’s blood and treasure.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“Worse than traitors in arms are the men, pretending loyalty to the flag, who feast and fatten on the misfortunes of the nation, while patriot blood is crimsoning the plains of the south, and bodies of their countrymen are mouldering in the dust.” –U.S. House Committee on Government Contracts, March 1863[/quote]

The era’s industrialists and financial elite, to be sure, included men who invested heavily in the Union to help the nation. But drawing the line between profiteering and the normal business practices of the period is not so easy. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles’ name is usually found in the pantheon of Union heroes. Nevertheless, Welles allowed his cousin, the purchasing agent George Morgan, to procure vessels for the Navy and receive what now might seem scandalously high commissions for them. Those commissions, however, were normal for the era.

Major General James Wolfe Ripley, the Union Army’s chief of ordnance from 1861 to 1863, is another leading figure sometimes called a war profiteer, although he more accurately should be considered a mere “obstructionist,” as he was opposed to the Army risking the adoption of any advanced weaponry, even when it might have helped the Union cause—particularly the Spencer repeating rifle.

Many business magnates rose to the challenge to help the cause, but regrettably their patriotic response was not universal. What should have been a time of national unity was instead exploited by some individuals and companies for personal gain. They shamelessly billed the government for products and services that were abysmally substandard or were never delivered. Their patriotism extended only as far as it benefited their pocketbooks.

War profiteering did not pick sides either—it flourished above and below the Mason-Dixon Line. Presented here is our Top 10 list of what Civil War–era author Henry Morford labeled the “shoddocracy” in his novel The Days of Shoddy.

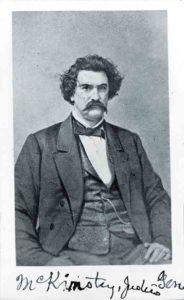

10. Brig. Gen. Justus McKinstry

A New York native, Justus McKinstry graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1838, and served in the Second Seminole War and the Mexican War. As a major in the spring of 1861, he was appointed quartermaster for the Department of the West under Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, who promoted him to brigadier general that September.

In April 1861, after the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor led to war, Frémont was tasked with creating a large army in a hurry, and he turned to McKinstry to purchase the necessary supplies. McKinstry in turn awarded government contracts to crooked suppliers, who would give him kickbacks.

McKinstry’s corrupt practices provoked multiple investigations, and in the fall of 1862 he was court-martialed and convicted of fraud and neglect of duty. He was dismissed from the service on January 28, 1863—the only general officer on either side to be dismissed for fraud.

Publicly shamed, unemployed, and deprived of his Mexi-can War pension, McKinstry ran through his ill-gotten wealth quickly. His wife and sons left him, and when he died in St. Louis in 1897, a final affidavit regarding his estate stated simply: “Said soldier left no property.”

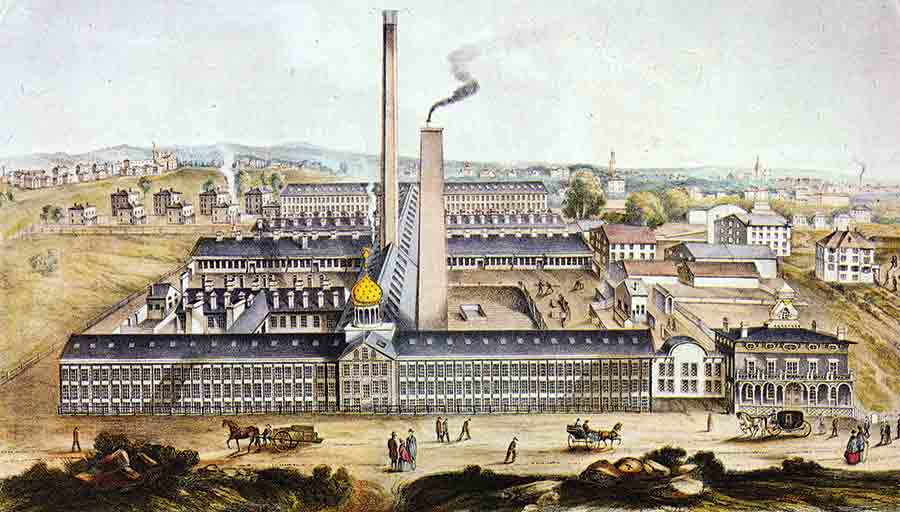

9. William Sprague IV

For William Sprague IV, success in politics was secondary to success in business. His family’s textile business, the A&W Sprague Manufacturing Company, established the world’s largest calico-printing mill in Cranston, R.I., supported by five textile mills across New England. In 1860 Sprague was elected governor of Rhode Island at age 29. In 1863 he was appointed to fill a U.S. Senate seat from Rhode Island and held that position until 1875.

The outbreak of war presented Sprague with a conflict. As governor he pledged his state’s support of the Union; however, the ban on the purchase of Confederate cotton threatened his business. Desperate, Sprague implored federal and military officials for a permit to bring Southern cotton past the Union blockade, but was denied.

In 1863 Sprague leaped at a scheme proposed by Texas blockade-runner Harris Hoyt. Sprague gave Hoyt money to buy three ships, one of which was sent to Havana and sold to a British straw man, allowing it to sail under the British flag and therefore immune from U.S. intervention. The ship then sailed to Matamoros, Mexico, just across the Rio Grande from Texas. In Matamoros, Hoyt traded the cargo (which included oils, nails, soap, butter, twine, medicine, and weapons) to Confederate officials for a load of cotton. The “British” ship then sailed to New York. Through this scheme, Sprague acquired hundreds of smuggled bales of cotton.

In December 1864, Union officials arrested Charles Prescott, skipper of one of the Sprague–Hoyt ships. Prescott confessed everything. Sprague responded by writing a panicked denial to Maj. Gen. John Dix, who was in charge of the investigation. Nevertheless, Sprague was arraigned on six charges of treason. Fortunately for him, Dix was also suspected of smuggling goods when he had commanded troops occupying Norfolk, Va. Due to Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, public attention rapidly shifted away from Sprague’s crimes—this self-serving profiteer was never convicted.

8. Samuel Colt

Samuel Colt’s “revolving pistol,” patented in 1836, represented a breakthrough in firearms technology and dominated the market for two decades. Colt devised a way to manufacture the revolver in several models, using innovative assembly-line techniques, and became one of America’s wealthiest men.

Colt apparently had no complaint with slavery and, in the 1850s, sold his revolvers to both Northern and Southern customers. But when the war broke out in 1861, public accusations that Colt was a Southern sympathizer convinced him to limit his sales to the North.

Production of a Colt revolver cost between $4 and $9. Colt sold revolvers to the British government for $12.50 and to American civilians for $14.50. Initially, however, he charged the U.S. government $25. The difference was pure profit. To ensure his market, Colt made generous donations to senior Northern politicians and gave them elaborately engraved Colt pistols. A comparable Remington revolver cost as little as $13, but Colt convinced Union procurement officers that his revolver was superior. During the war, Colt’s Manufacturing Company of Hartford, Conn., sold hundreds of thousands of revolvers to the government, while Remington sold only a few thousand prior to mid-1863.

Colt died in 1862 at the age of 47. He left his wife and son an estate valued at around $15 million (equivalent to about $350 million today).

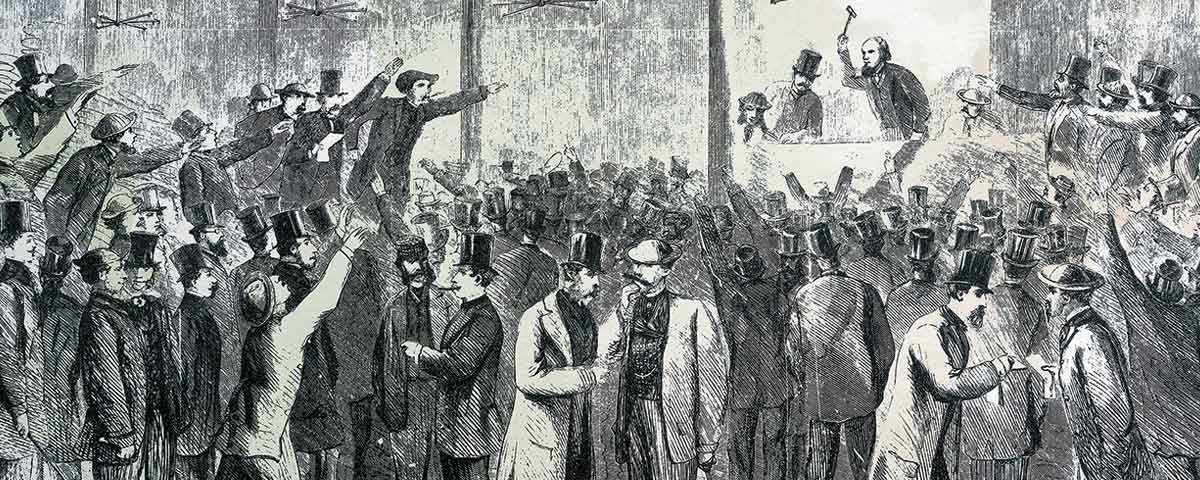

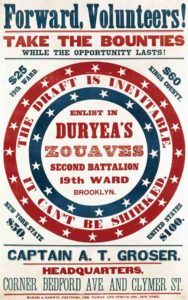

7. Bounty Jumpers

Although many Civil War soldiers were volunteers, as the war dragged on both the Union and Confederate governments resorted to conscription to fill their armies’ ranks. Until 1864, draftees were permitted to hire substitutes, as finance magnate J.P. Morgan notably did to avoid military service. Groups of draft-eligible men pooled funds as a sort of insurance to hire a substitute in case any member was drafted. Families could decide which family member would go to war and who would stay home.

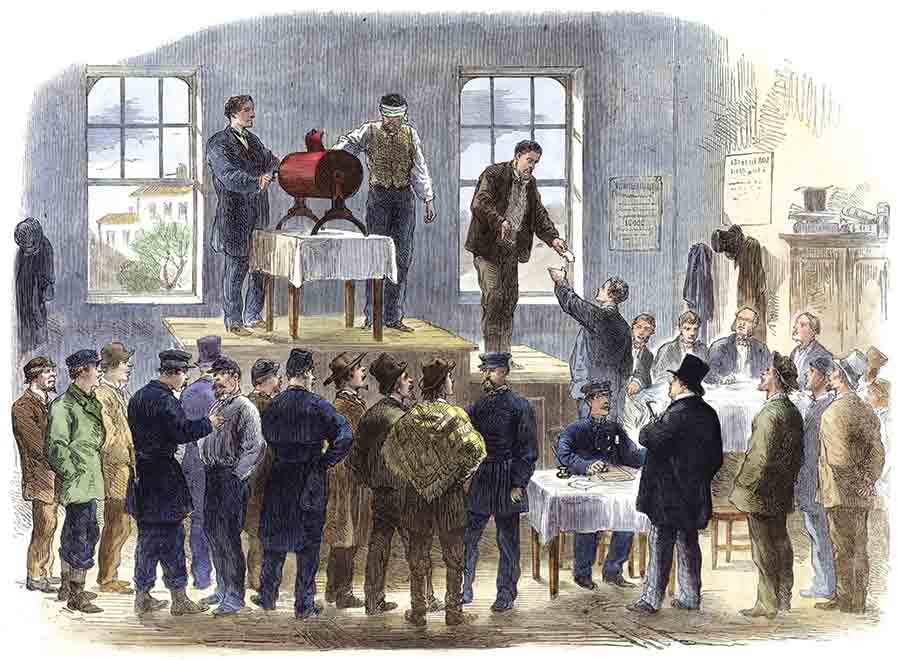

Local, state, and national authorities also offered cash bonuses to lure men to enlist. “Bounty jumpers” arose to take advantage of this system. They would enlist as a substitute, collect a bounty, then desert from their unit before reaching the front lines. After traveling to a new area, the bounty jumper simply repeated the lucrative process. One scoundrel, John Larney, claimed to have collected bounties from 93 Ohio, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New York regiments.

The practice was more profitable in the North, where bounties started at $300, compared to payments of $50-$100 in rapidly devaluing Confederate dollars. With Northern state and local governments adding funds to a Union bounty, the amount could easily exceed $1,000.

By 1864 bounty jumping had become a capital crime, and perpetrators were more likely to be executed than military deserters.

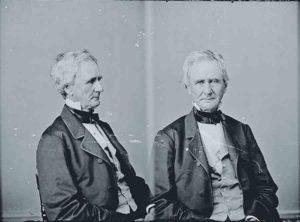

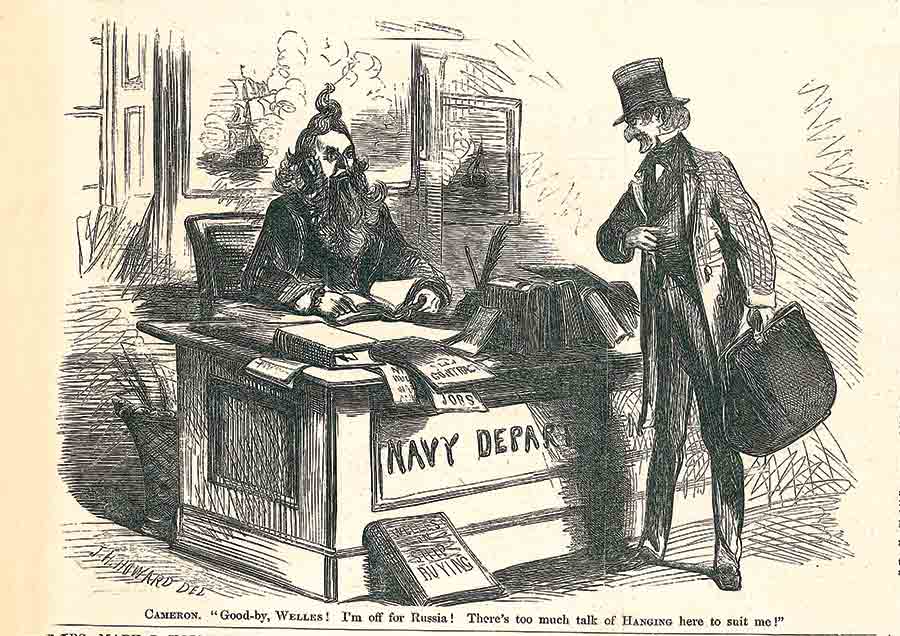

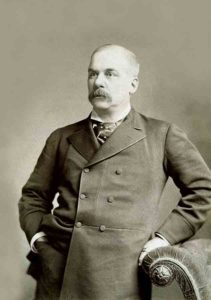

6. Simon Cameron

Born into poverty in 1799, Pennsylvanian Simon Cameron relied on his charm to rise through a series of business positions. Before the Civil War, he made a fortune in railroads and canals and invested his fortune in the banking industry, then gave low-interest loans to politicians to buy his way into politics. Before the election of 1860, he had been a Whig, a Democrat, and a “Know-Nothing,” leaving each party when he could no longer manipulate it to his benefit.

He was elected to the U.S. Senate as a Democrat in 1845, but left the party in 1849 after failing to get reelected. He returned to the Senate in 1857 as a Republican. Unsuccessful in his quest for the Republican nomination for president in 1860, he used his influence to support former Illinois congressman Abraham Lincoln.

To show his appreciation, Lincoln appointed Cameron to his Cabinet as secretary of war. Northern newspapers quickly began reporting evidence of underhanded dealings. Lucrative government contracts for goods and services went to Cameron’s friends. He purchased defective muskets, threadbare uniforms, spoiled barrels of pork, and blankets that were never delivered.

Cameron used his contacts in the railroad industry to avoid the appearance of profiting from this mess. Rather than sending payments directly to Cameron, merchants and traders would overpay to ship their goods on railroads in which Cameron had invested.

By the end of 1861, Cameron had become a liability. Lincoln pushed him to resign as secretary of war on January 14, 1862, but because of Cameron’s political control of Pennsylvania, the president awarded him the ambassadorship to Russia. He stayed there for less than a year, and eventually returned to the Senate two years after the war.

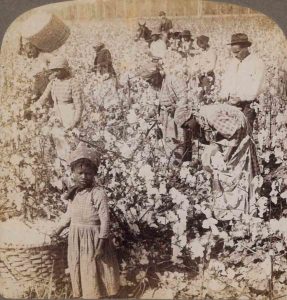

5. Southern Plantation Owners

The South’s large plantation owners proved reluctant to sacrifice for “the Cause.” For example, after the capture of New Orleans in April–May 1862, Union Flag Officer David Farragut pushed upriver in a failed attempt to capture Vicksburg, Miss. Although Farragut didn’t succeed in capturing the city, his Union fleet’s proximity to the riverside plantations (and his promises to confiscate slaves along the way) frightened so many proprietors that they abandoned their plantations altogether and moved their slaves deeper into the Confederacy, where it would be harder for them to escape to Union lines. The planters’ departure secured their “property” (the African Americans they held in bondage) but seriously weakened Confederate forces by denying access to supplies and foodstuffs that could have been grown on the riverside plantations.

Meanwhile, as food shortages spread throughout the South, the Confederate government encouraged—but could not legally compel—planters to grow corn and other food crops. Many planters preferred growing profitable cash crops—cotton and tobacco. Even when condemned by their government, a large number of planters chose to continue growing cash crops, which could be smuggled out of the Confederacy and sold for exorbitant prices. Cotton, which had gone for as little as 10 cents a pound in 1860, soared to $1.89 a pound by 1863.

Owners of large plantations had the connections and the resources to smuggle cotton to mills in Britain and even the North, reaping tremendous profits. What couldn’t be sold immediately, moreover, could be held until the end of the war, when it was expected to sell for at least $1 a pound. Even Southern farmers with smaller holdings who were far from the front lines questioned their government’s expectation that they should support the Confederate war effort by growing low-paying food crops to feed faraway soldiers.

Ultimately the lack of food was as effective as any military tactic in breaking the Confederacy. Starving soldiers and civilians eventually lost the will and, most important, the strength to fight.

4. DuPont Powder Company

Defense contractors are a principal beneficiary of warfare. E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, commonly known as DuPont, was established in 1802 as a gunpowder mill. Although the Civil War cut off profitable sales to Southern customers, Union military contracts more than made up for any lost business.

The federal government’s increased demand for gunpowder quickly depleted DuPont’s available resources. Recognizing the need for potassium nitrate (saltpeter), a key ingredient in gunpowder, the Union paid to send DuPont’s leading chemist, Lammot Du Pont, to England in November 1861. With $3 million in hand, he purchased enough saltpeter to supply the Union Army for at least three years.

By the end of 1862, DuPont had increased its price per pound of gunpowder to 18 cents, up 2 cents (more than 10 percent). DuPont blamed the increase in price on the rise in cost of materials and the difficulties associated in obtaining saltpeter, but neglected to mention that the government had already paid for it.

In March 1863, the Lincoln administration pushed back against DuPont’s price increase by passing a tax on profits, amounting to 1 cent per pound on gunpowder. DuPont accordingly raised the price of its gunpowder to an unprecedented 26 cents per pound. In November 1863, the government added another half-cent tax; DuPont raised its price to 30 cents per pound. The U.S. Treasury by then was so depleted it was unable to make immediate payment, forcing DuPont to wait for more than the half a million

dollars in tainted profits it was due—worth $7 million today.

3. Brooks Brothers

The four Brooks brothers—Elisha, Daniel, Edward, and John—took over their family’s New York clothier business in 1850. Prior to the Civil War, Brooks Brothers introduced a popular ready-to-wear suit and provided uniforms for several state militias.

Brooks Brothers provided suits for President Lincoln, as well as dress uniforms for many Northern generals, including Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, Philip Sheridan, and Joseph Hooker. On the night he was assassinated, Lincoln was wearing a Brooks Brothers frock coat.

At the beginning of the war, the state of New York placed an order for 12,000 Union-blue uniforms, including jackets, coats, and trousers. The contract was open to competitive bidding, but given the urgency of the war, potential suppliers were given only 24 hours to submit a bid. Most firms placed bids based on the current availability of the correct cloth, but Robert Freeman, representing Brooks Brothers, claimed that only his firm could supply the necessary material. He committed to delivering 2,000 uniforms each week.

Within days it became clear that not only did Brooks Brothers not have the necessary material, there wasn’t even enough material available in the local market to complete the order. Brooks Brothers received permission to substitute a gray cloth of equal quality but instead used substandard, recycled or remanufactured wool material known in the garment industry as “shoddy.” The cloth was shabby and irregular in color, with dark gray stripes, patches of green, and spots of brown. Its texture was gritty and uncomfortable. It began to fall apart within weeks, unable to withstand rain or even regular wear. Furthermore, the workmanship was dubious at best. Some jackets were missing either buttons or buttonholes, while seams remained unsewn.

Fingers pointed in every direction. Under questioning from the New York legislature, Elisha Brooks refused to divulge how much money his company had saved by substituting “shoddy” cloth, but he and his company were eventually forced to replace about 2,300 uniforms at a cost of more than $45,000 (approaching nearly $1 million today). So widespread was the problem of overpayment for inferior products, the word “shoddy” itself evolved to describe anything, not merely clothing, of poor quality or substandard workmanship.

2. George Opdyke

New Jersey native George Opdyke lived in Cleveland and New Orleans as a young man. He learned the textile business and made a small fortune selling poor-quality garments to Southern plantation owners to clothe their slaves. By 1832 he moved to New York and operated a large clothing factory. Now a millionaire, he also entered politics. He served a term in the state legislature and lost his first bid for New York City mayor in 1859.

Alongside his rivals, the Brooks brothers, Opdyke took huge orders from the military to produce uniforms, boots, belts, caps, and haversacks. Elected mayor in December 1861, Opdyke used his position to approve uniforms produced by his factory using the same “shoddy” cloth making up the defective Brooks Brothers uniforms. In addition to shoddy cloth uniforms that quickly fell apart, Opdyke’s factory produced other substandard military equipment: boots with soles made from glued-together wood chips that fell apart on the march and glued-together haversacks that likewise disintegrated. Opdyke’s support for the war backfired in the summer of 1863, when protests over the new conscription laws led to widespread rioting and violence in Manhattan, in what became known as the New York City Draft Riots. Opdyke’s support of these laws drew hostility, and many of his factories and warehouses were looted and burned to the ground. His political reputation suffered greatly, and he lost the mayoral election held later that year.

Opdyke’s woes didn’t end there. After the Republican National Convention in 1864, Albany Evening Journal editor Thurlow Weed, the state’s premier power broker, began using his newspaper to attack political opponents, including Opdyke. Weed alleged that Opdyke was a secret partner in a munitions company that received nearly $200,000 from the city of New York after one of their factories was destroyed during the 1863 Draft Riots, while Opdyke was mayor. Further, Weed alleged, Opdyke had received millions more from extorted payments, kickbacks, bribes, and a secret partnership with the Brooks brothers.

Opdyke responded by suing Weed for libel. The trial lasted nearly a month. Finally, with Opdyke’s nefarious dealings clear to jurors, Weed’s trial ended on January 11, 1865, in a hung jury. Apparently, the jurors could not agree upon whether Weed should be completely acquitted or be required to pay a nominal amount of 6 cents in “damages.” Opdyke did not hold public office again, but he was never charged with treason or held responsible for sending substandard-quality materials to the military.

1. J.P. Morgan

Born in 1837, John Pierpont Morgan, founder of J.P. Morgan & Co., was a financier and banker. He specialized in corporate finance, becoming known for taking over and reorganizing troubled businesses. During the postwar Gilded Age, he arranged the merger of Edison General Electric and Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric. He was also involved in the formation of AT&T, Chase Manhattan Bank, International Harvester, and U.S. Steel. He was ranked by Forbes.com as the second most influential businessman of all time. At the beginning of the Civil War, though, he was just 23 years old and operating his first business out of a one-room office in New York, with the help of a $300,000 loan from his father.

In August 1861, Morgan used his political connections to purchase 5,000 Hall .52-caliber, breech-loading carbines from the War Department. These obsolete, Mexican War–era rifles had been condemned by the Ordnance Department, and their breech-loading mechanisms had a dangerous proclivity to explode upon firing, often killing or maiming soldiers. The government was liquidating them as scrap metal at the bargain-basement price of $3.50 each.

Morgan’s operatives approached Department of the West commander John Frémont and offered to sell him 5,000 rifles at $22 each. Frémont, desperately in need of small arms, readily agreed to the outrageously inflated price. Morgan completed the sale of the guns before he had actually completed the purchase, allowing him to pay for it with the money from the sale and pocket the $92,500 difference.

Morgan had the rifles re-bored to the standard .58-caliber, thereby making the barrels weaker and increasing the risk of the weapons’ exploding. When federal officials belatedly realized they’d been had, the money had already changed hands and there was nothing they could do. Morgan, incidentally, avoided any personal Civil War military service by hiring a substitute for $300—about the amount of profit he pocketed from selling 16 of his defective Hall rifles.

Melinda Musil, a regular contributor to America’s Civil War, writes from Independence, Mo.—in the heart of the Trans-Mississippi Theater.