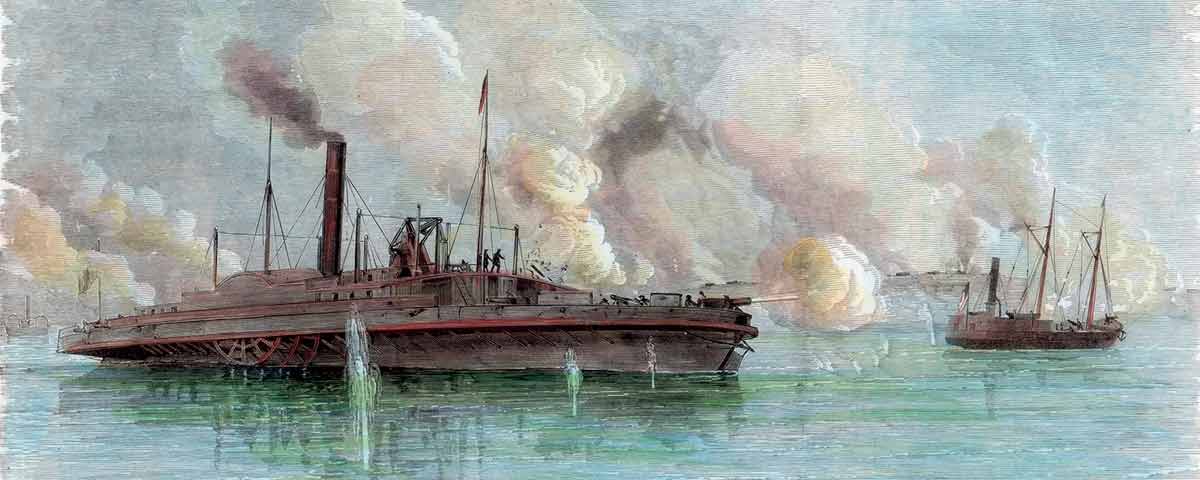

Before dawn on September 8, 1863, the gunners of Company F, 1st Texas Heavy Artillery—known as the Davis Guards, in honor of the Confederate president—aimed their contingent of cannons at a Yankee flotilla steaming toward the rudimentary earthworks of Fort Griffin. The fort, with its complement of two 24-pounders and four 32-pounders, guarded Sabine Pass, the narrow waterway on the Louisiana–Texas border connecting the Sabine River with the Gulf of Mexico. Major General Nathaniel Banks had dispatched the Yankee armada, under the command of Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin, to storm the pass and capture the fort, as the first step in the Union occupation of Texas. The four gunboats in the vanguard mounted 18 guns, while the two dozen or so transports behind them carried some 5,000 troops. Inside the fort, outnumbered more than 100–1, stood Company F’s 48 men—45 enlistees, their lieutenant, an engineer, and a surgeon. The lopsided battle that followed would mark one of the Civil War’s most extraordinary engagements.

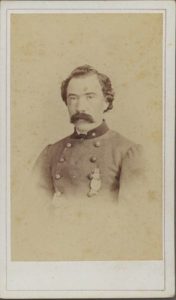

The Davis Guards were all Irishmen, selectively gleaned from the docks of Galveston and Houston. Their lieutenant was the affable, enterprising Richard W. “Dick” Dowling. As a boy, he had immigrated with his family to New Orleans from County Galway. When his parents and four of his six siblings died of yellow fever, the teenage Dowling moved to Texas, eventually opening several saloons in Houston and co-founding what became the Houston Fire Department.

Photography Collection)

Eight months earlier, the Davis Guards had repelled the Union Navy’s first attempt to capture Confederate defenses and seize Sabine Pass. Anticipating another attempt on Fort Griffin, Dowling’s artillerymen set up a progression of range-marking stakes at specific distances from shore, and honed their artillery skills daily. They practiced for both speed and accuracy, and by the Union gunboats’ second arrival there, they were as ready as time, skill, and training allowed.

Between 6 and 7 a.m. on September 8, the Union gunboats hove into view, intending to clear a path for the transports to land the thousands of Federal infantrymen. Clifton was the first to open fire on the fort. The sidewheel steamer shelled Fort Griffin from a distance too great for the Rebel artillery to reach, and Dowling’s gunners simply took cover until the shelling subsided. By mid-afternoon, Clifton, along with the three other Yankee gunboats, moved closer, each of the four vessels taking one of the two channels that led toward shore. When they came within 1,200 yards, the six Rebel guns unleashed a torrid barrage, Dowling’s men shouting “Victory or Death!”

One of the fort’s guns quickly jumped its platform, but the remaining five proved sufficient. Soon a well-placed shell struck the gunship Sachem’s boiler; several of the crew were killed or wounded as it blew up. Now adrift in the channel, the crippled vessel also blocked the passage of fellow gunboat Arizona.

In the other channel, sharpshooters on Clifton delivered a fusillade at the fort when the ship came within a quarter-mile of shore. Undaunted, a Rebel gun crew responded with a round that severed Clifton’s tiller rope, forcing it to run aground. The Federal riflemen gamely continued to fire, but a well-placed shell smashed into Clifton’s boiler, driving the crew and complement of soldiers over the side.

With two disabled gunboats now Confederate prizes and a third blocking the channel, the fourth Yankee vessel, Granite City, withdrew rather than risk a similar fate. The infantrymen waiting in the Union transports never had the chance to step ashore. Franklin’s invasion force steamed back in shame to New Orleans.

The battle lasted less than 40 minutes. The Davis Guards fired 137 times—a remarkable rate of one round every two minutes or less, considerably faster than heavy artillery crews of the time were accustomed to. Dowling daringly ordered his men not to swab their cannons between shots, risking an in-bore explosion, but it proved a wise decision. According to the Texas State Historical Association, the Guards did not suffer a single casualty while killing 50 Yankees and taking prisoner about 350 sailors and soldiers.

News of the Second Battle of Sabine Pass reached all areas of the Confederacy, making an instant hero of Dick Dowling and the Guards. President Jefferson Davis called the victory “more remarkable than…Thermopylae” and requested that Congress order a special medal struck for each member of the Guards. Congress complied, and in addition passed a resolution of thanks, calling the victory “one of the most brilliant and heroic achievements in the history of this war.” On one side of each medal are the initials “DG” and either a Confederate flag or a Maltese cross, and on the other, “Sabine Pass, Sept. 8, 1863,” along with the recipient’s name.

After the war, Dick Dowling returned to Houston, where he expanded his business interests to include oil and gas leases and real estate investments. Prosperity, however, would be short-lived. Ironically, Dowling had survived the war without injury, only to fall victim to yellow fever—the same malady that had claimed so many of his family—just two years after the war. Several years after his death, the city fathers named a street after him, and in 1905 erected a statue of the “hero of Sabine Pass” in Houston’s Hermann Park.

Ron Soodalter, a regular contributor to America’s Civil War, is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon.