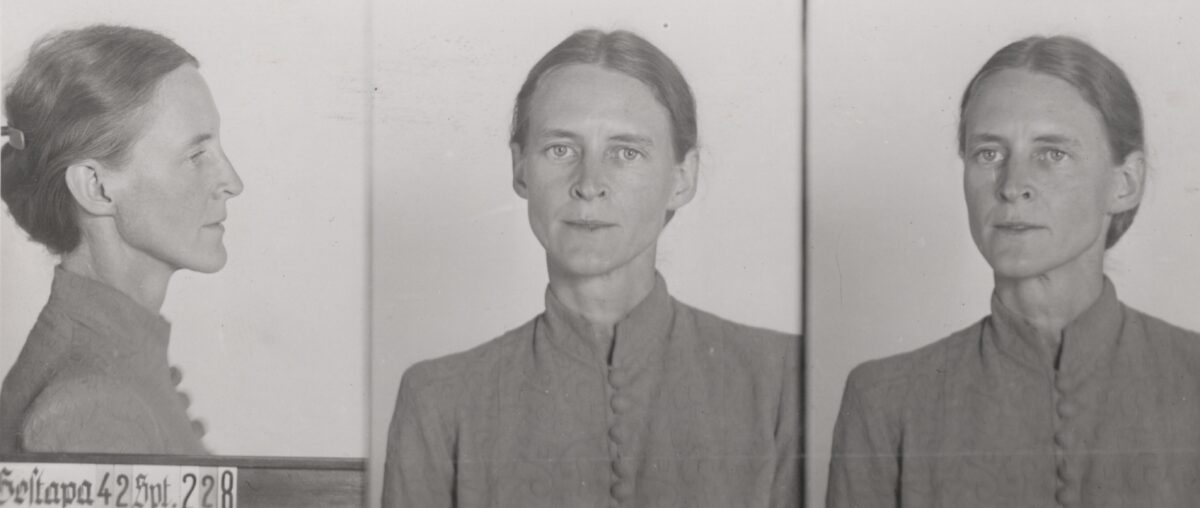

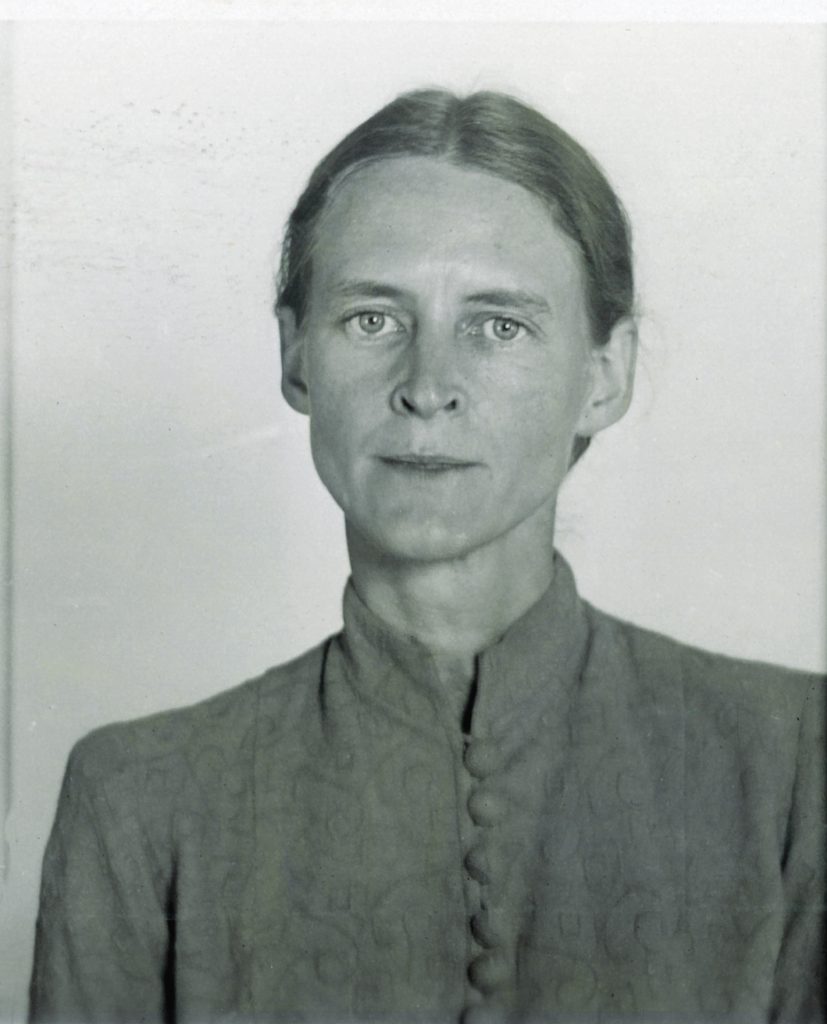

SHORTLY BEFORE 9 A.M. on December 15, 1942, Mildred Harnack entered a courtroom in Berlin. She wore a gray wool suit jacket and skirt. Her long, wheat-colored hair was pulled back in a bun. She had spent the last three and a half months locked in a dank prison cell, and despite her best efforts to make herself presentable she was unmistakably ill. A persistent cough racked her lungs, ravaged by tuberculosis she’d contracted in prison. Her body bore evidence of torture. She cut an unusual figure here at the Reichskriegsgericht—or Reich Court-Martial, an organ of the Wehrmacht High Command. Usually, the defendants brought to this courtroom were German military men—soldiers charged with desertion, or officers charged with insubordination. Mildred Harnack was an American civilian.

Born and raised in Milwaukee, she had attended graduate school at the University of Wisconsin, where she met her German husband, Arvid, also a graduate student. She followed him back to Germany in June 1929 and enrolled in a German PhD program shortly before Hitler became chancellor in 1933. Alarmed by Hitler’s popularity, the couple began holding clandestine meetings in their Berlin apartment to discuss how best to oppose the Nazi Party. What began as a small, scrappy cluster of students, friends, and friends-of-friends grew over the course of the decade, intersecting with other resistance circles. Their strategies of opposition were various. Some of them produced and distributed leaflets that denounced the Nazi regime and called for revolution. Some helped Jews escape Germany by securing immigration visas through diplomatic channels or by forging identity cards and exit papers. Some plotted acts of sabotage. Some obtained top-secret information about Germany’s political, economic, and military developments, and some passed this intelligence to Hitler’s enemies. Mildred Harnack was familiar with all these strategies and had participated in most. Now she was charged with treason, the only American woman in a secret mass trial at the Reichskriegsgericht that would involve more than 17 court proceedings and 76 defendants between 1942 and 1943.

She sat in a wooden chair at the back of the courtroom. One by one, 11 of her German co-conspirators, including her husband, entered and took their seats. Across the Atlantic, Mildred’s family knew nothing about the trial or even her arrest. Two of her siblings lived in Wisconsin, another in Maryland. The last letter she’d sent to them was dated August 14, 1942, enclosed in an envelope with a Swiss postmark. It was a carefully worded, enigmatic missive. “Despite our being separated,” Mildred wrote, “let’s not be worried and anxious.”

Five judges sat on a raised platform, peering down at the defendants. The prosecutor stepped forward. He’d been handpicked for the job by Hitler’s right-hand man, Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring. The prosecutor—who’d earned the sobriquet “Hitler’s Bloodhound”—aimed to convince the judges that Mildred Harnack and her German co-conspirators were spies in a sprawling Soviet espionage network that encompassed seasoned operatives and agents in Moscow, Paris, Geneva, and Brussels. He had a name for them: the Rote Kapelle—Red Orchestra. Mildred had never heard of this name, nor had anyone else in her resistance group.

Under German criminal law, there were two types of treason: treason against the government (Hochverrat) and treason against the country (Landesverrat). The former was punished with a prison sentence of three to five years; the latter was punished with death. Mildred Harnack stood up from her chair and approached the stand, hoping for mercy.

MORE THAN A DECADE earlier, Mildred Harnack was a 29-year-old graduate student lecturing about American novels at the University of Berlin while pursuing her PhD dissertation. She didn’t hide her political opinions. Capitalism, in her view, was broken. The Great Depression was devastating the lives of so many Americans, and Germans seemed similarly doomed; every day she encountered Berliners dressed in rags, begging for food, stirring her sympathy. Her university lectures moved fluidly from William Faulkner’s novels to the prevalence of the poor in Germany and the worrisome ascent of the Nazi Party. “It thinks itself highly moral,” she wrote in 1932, “and like the Ku Klux Klan makes a campaign of hatred against the Jews.” At the University of Berlin, she kept an eye out for German students who appeared to oppose the Nazis. By studying her students’ reactions to her lectures, which included pointed questions about Germany’s political climate, she could get a sense of who might be receptive to joining the underground resistance. It was a recruitment technique that required tremendous patience and shrewd intuition.

In the summer of 1932, Mildred was fired from the University of Berlin. It was clear to her that encouraging students to express their political beliefs would not be tolerated by the university’s administration. That fall she started teaching at the Berliner Städtisches Abendgymnasium für Erwachsene—the Berlin Night School for Adults, nicknamed the BAG. The BAG admitted working-class and unemployed Germans, a segment of the population that the Nazi Party relentlessly targeted with propaganda. She continued to use the classroom as a forum for political discussion and a source for recruitment. In fact, several of Mildred’s recruits from the BAG were among the most dedicated members of their resistance group, which she privately referred to as “the Circle.”

The Circle intersected with three other resistance circles—Tat Kreis, Rittmeister Kreis, and Gegner Kreis—forming an interlocking chain. They included factory workers and office workers, students and professors, journalists and artists. They were Jewish, Catholic, Protestant, atheist. Initially, their weapon of choice was anti-Nazi leaflets. They slipped the leaflets into mailboxes, left them in piles in factories and U-Bahn stations. But leaflets were a poor weapon against a fascist dictatorship, and easily exposed them to arrest. Mildred hoped to form a more effective resistance network, one that extended across Germany’s borders.

She got hired as a literary scout for the Berlin-based publishing company Rütten & Loening. The job was her cover—a sly way for her to journey to other countries and meet with contacts in the resistance. Her American passport was valuable, enabling her to travel more freely than her German co-conspirators. She went to France, England, Switzerland, Denmark, Norway. In 1935, Arvid Harnack got a job at the Ministry of Economics to gain access to classified documents about Hitler’s operational and military strategies. Mildred and Arvid both participated in passing this intelligence to other countries.

That Mildred and the others were part of an espionage network run by the NKVD—the Soviet secret police—and the GRU, or Red Army intelligence, is well documented in British, U.S., and Soviet intelligence files. Nowhere in these files is there any mention that she also passed intelligence to the United States. But Mildred was in fact an informant for the U.S.—something we know from primary source documents housed at the Hoover Institution and the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library archives, and from interviews with survivors of the resistance.

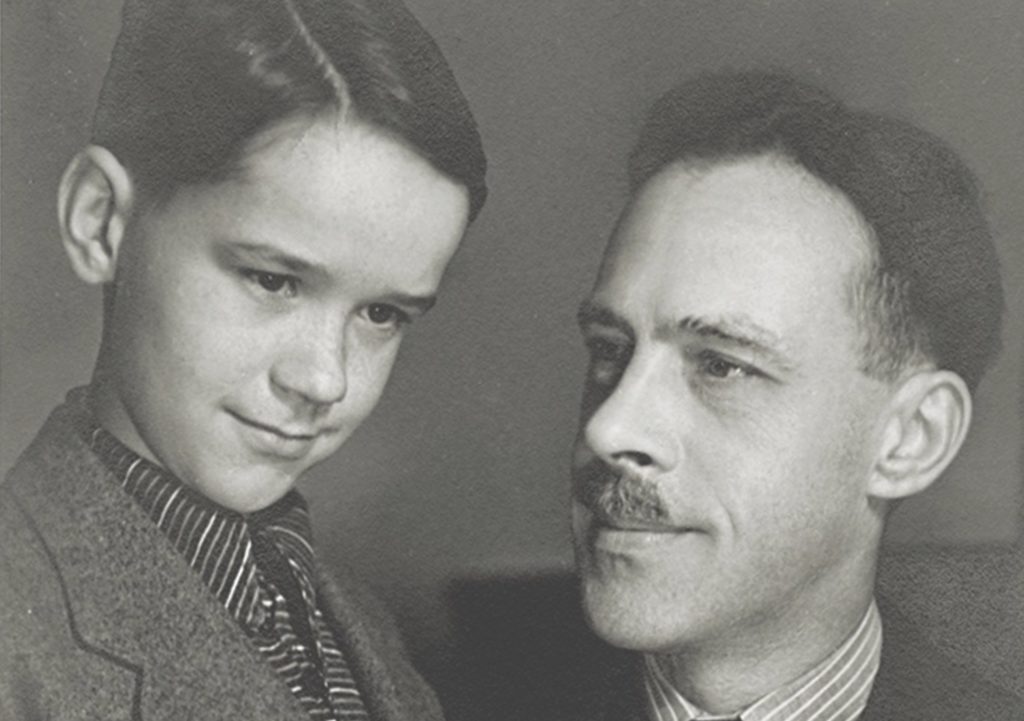

One of those survivors, an American, was a boy at the time. After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Don Heath helped Mildred Harnack pass intelligence to the United States. He was the son of Donald R. Heath Sr., a diplomat at the U.S. Embassy in Berlin known to his State Department colleagues as “Morgenthau’s Man.”

Several years earlier, Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. had decided that the reports that diplomats at the U.S. Embassy in Berlin cabled to Washington were of little use to him—often not much more than digests of newspaper articles or gossip gleaned from foreign diplomats at embassy functions. Morgenthau wanted facts, figures, and feet-on-the-ground intelligence about Germany’s Reichsbank and Ministry of Economics. He wanted to know whether Germany planned to pay its formidable debts to American creditors. He also wanted to know whether Hitler was indeed preparing to wage war in Europe and how he planned to finance it. So, at a time when the United States lacked a centralized intelligence agency, he dispatched Donald R. Heath to Berlin as an ad-hoc agent.

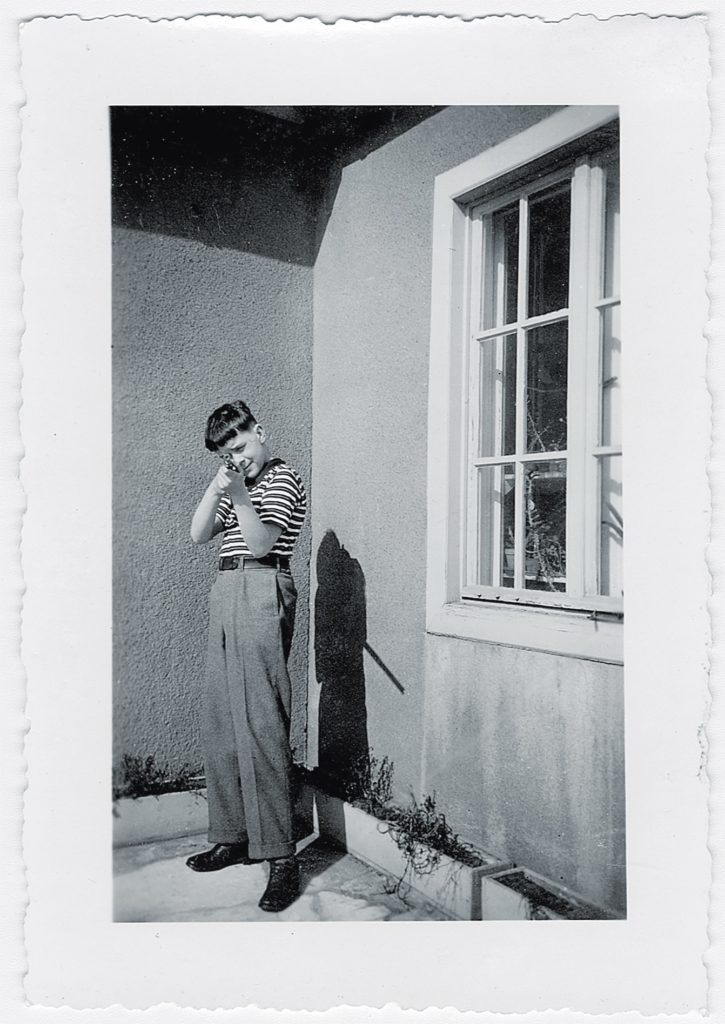

On a cold December morning in 1939, young Don dashed out the front door of his home at Innsbrücker Strasse 44. He was a freckle-faced 11-year-old, swift on his feet. He ran to the U-Bahn station at Rathaus Schöneberg, a blue knapsack stuffed with books on his back, and leapt onto the train. He was on his way to Woyrschstrasse 16, where the Harnacks lived. Don had previously attended the American School on Platanenallee in Berlin, but it was shuttered now that war had broken out. Most American diplomats sent their children to boarding schools in Switzerland or back in the States, but Donald R. Heath and his wife, Louise, decided to keep their son in Berlin. They wanted to help the resistance and had made a clandestine arrangement with Mildred Harnack to meet with their son twice a week.

Once Don arrived at the building, he raced up the stairs to the fourth floor. Mildred appeared at the door wearing a modest dress favored by women in the Nazi teacher’s union. She was leading a double life, masquerading as an American wife who was as devoted to the Nazi Party as her German husband. Mildred invited Don into the apartment, where he remained for an hour or so, seated beside her on a sofa with wooden armrests, a book in his lap. The ostensible purpose of these twice-a-week meetings was for Mildred to give Don lessons in English and American literature, but there was another purpose as well.

Between the ages of 11 and 13, Don Heath was Mildred’s courier, his book-crammed knapsack a receptacle for carrying information to his father. Donald R. Heath instructed his son to take a different route to her apartment building each time he visited her. Sometimes Don entered the Kaufhaus des Westens department store through one door and exited through another, sometimes he climbed the stairs to the steeple of the American Church near Nollendorfplatz, and sometimes he took a long detour through the Berlin Zoo. On Sundays, the Harnacks and the Heaths went on walks in the Spreewald, a forested region 60 miles southeast of Berlin, where they felt reasonably safe exchanging information. Don Heath played the role of lookout, running along tree-lined paths, keeping an eye out for passers-by.

On September 10, 1940, a British bomb exploded near the U.S. Embassy. In his book Berlin Diary, American journalist William Shirer estimated it was roughly 150 yards from the Brandenburg Gate. A splinter from the bomb “crashed through the double window of the office of Donald Heath…,” Shirer wrote, “cut a neat hole in the two windows, continued directly over Don’s desk, and penetrated four inches into the wall on the far side of the room.” Another bomb detonated near the Heath’s residence on Innsbrücker Strasse, shattering the windows. Don Heath, then 12, was deeply shaken. As he recalled decades later, in a 2016 interview, “I was blown off the bed.”

The Heath family left Berlin in June 1941 after Donald R. Heath was abruptly transferred to Santiago, Chile. Available archival records don’t elaborate on the reason for the transfer.

With Mildred Harnack’s primary connection to the U.S. Embassy severed, she deepened her involvement in Soviet espionage. Over the previous six months, Arvid Harnack and co-conspirator Harro Schulze-Boysen, a senior lieutenant in the Luftwaffe, had deluged Moscow with detailed reports about Hitler’s plans to invade the Soviet Union—warnings that Stalin ignored, as he did those that came in from sources in Britain and the United States and from a Tokyo-based Soviet agent named Richard Sorge. Mildred enciphered reports sent by shortwave radio transmitters to Moscow Center, and others in the Circle operated the radio transmitters. They were hastily trained, and mistakes were many.

Four days after the launch of Operation Barbarossa on June 22, German agents in the Funkabwehr—the signals-intelligence branch of the German military intelligence service, the Abwehr—intercepted an enciphered message sent by a radio transmitter. A year later, the Funkabwehr cracked the cipher wide open.

The Gestapo arrested Harro Schulze-Boysen on August 31, 1942. Mildred and Arvid Harnack fled Germany, planning to escape to Sweden. A high-ranking SS officer named Horst Kopkow drove 500 miles in pursuit of them, tracking them down in Nazi-occupied Lithuania on September 7, 1942. Mildred and Arvid were led in shackles to the basement prison at Gestapo headquarters in Berlin. Over the ensuing weeks, the prison would fill with men and women in the resistance. Many Mildred had never met face-to-face; she knew them by their deeds alone: the one who was a courier, the one who stashed a radio transmitter in her apartment, the one who wrote leaflets, the one who distributed them. The basement prison soon overflowed with prisoners, and arrangements were made for other prisons to accept the spillover. The men were sent to men’s prisons, the women to women’s prisons. Mildred was locked in a solitary cell at the Charlottenburg women’s prison, a redbrick building concealed behind a walled courtyard on Kantstrasse.

Every morning she was transported in a police wagon to Gestapo headquarters to be interrogated by Walter Habecker, a sadistic Nazi with a black smudge of a moustache that matched Hitler’s. Habecker had an affection for thumbscrews, calf clamps, and other, more severe, instruments of torture. Confessions extracted during interrogations were admitted as evidence for the mass trial.

Mildred Harnack’s trial lasted four days. On December 19, 1942, the panel of five judges convicted her of being an accessory to treason against the country and sentenced her to six years at a prison camp. Arvid and all but one of the others were convicted of treason against the country and variously sentenced to death by hanging, firing squad, or guillotine. But Hitler, who received daily reports of the trial, overruled Mildred’s sentence and ordered her execution. On February 16, 1943, at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin, she was strapped to a guillotine and beheaded.

IN 1946, THE U.S. Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) opened an investigation into the execution. “Mildred Harnack’s actions are laudable,” a war crimes liaison officer wrote in a top-secret memo dated November 21, 1946, noting the “rather extensive file” they had on her. In another top-secret memo, he observed: “Mildred Harnack was in fact deeply involved in underground activities aimed to overthrow the government of Germany.” A higher-ranking colleague reprimanded him: “This case is classified S/R [secret/restricted] and should not have been referred for investigation. Withdraw case from Detachment ‘D’ and do not continue the investigation.” The CIC buried her case.

Still, news about her execution leaked out. On December 1, 1947, the New York Times ran a story: “With comprehensive knowledge of the German underground movement, Mildred Harnack stood up courageously under Gestapo torture and revealed nothing.” A few days later, the Washington Post observed that she was “one of the leaders in the underground against the Nazis.”

Immediately after the war, American and British intelligence agencies had recruited high-ranking Nazis, regarding them as valuable sources of information about Soviet tradecraft. Two of these Germans were directly involved in arresting, prosecuting, torturing, and executing Mildred Harnack, and played a large role in altering for decades how she would be remembered.

Hitler’s Bloodhound—the Reichskriegs-gericht prosecutor otherwise known as Manfred Roeder—was on the verge of being indicted as a war criminal at Nuremberg in 1947 when the CIC whisked him away to a secret location and disguised his identity with the code name “Othello.” It believed that he possessed “a wealth of information” that could be valuable to the United States. Roeder fed them the fiction that Mildred Harnack and her co-conspirators had been members of a massive Communist espionage ring that was “still alive and active” in the United States.

British intelligence was likewise duped by the Nazi who personally arrested Mildred Harnack and oversaw her torture. In 1945, Horst Kopkow told his British captors that he could provide valuable information about this sprawling Communist espionage ring, including “Russian plots against British interests.” MI6 agents faked Kopkow’s death and gave the former SS officer a new identity as the manager of a textile factory in West Germany, “Peter Cordes.”

Neither man faced trial at Nuremberg. By May 1948, the CIC had dropped Manfred Roeder as a source. Benno Selke, the deputy director of the Evidence Division at Nuremberg, castigated the CIC for recruiting Roeder, “one of the most hated men in Germany,” a “notorious, unscrupulous, opportunistic Nazi.” Roeder went on to become the deputy mayor of his hometown of Glashütten and died at the age of 71. Exactly how long Horst Kopkow remained as a source for MI6 remains unknown; Kopkow spent the rest of his life in the city of Gelsenkirchen, dying at age 85.

In 1998, under a mandate from the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act, the CIA, FBI, and U.S. Army began releasing records once classified as top-secret, a process that continues to this day. This information provides conclusive evidence that Mildred Harnack’s involvement in the underground German resistance was viewed through a Cold War lens. As early as 1946, a CIC officer evaluating Mildred Harnack’s case concluded that her execution by guillotine was “justified.”

Nearly 80 years after her death, we now have both the perspective and documentation to regard Mildred Harnack with more nuance and depth. According to all available records, she was the only American in the leadership of the German underground resistance during the Nazi regime. She had numerous opportunities to return to the United States, but chose to remain in Germany. At a time when Hitler ruled with the consent of so many Germans, an American woman risked—and lost—her life fighting him. In Wisconsin, the state legislature has instituted a “Mildred Harnack Observance Day,” a school bears her name, and in 2019 the city of Madison erected a monument to commemorate her as a “WWII Resistance Fighter.” Still, few people know of her, and the smattering of books and articles produced since her execution in 1943 are replete with errors that over time have calcified into fact.

I was about nine when I first heard Mildred Harnack’s name. It was during a visit with my great-grandmother, who lived in Chevy Chase, Maryland. I remember gazing at a long line of horizontal pen marks on the kitchen wall. My great-grandmother instructed me to stand against the wall, placed a ruler on my head, and measured my height. I looked at my mark, and I looked at the other marks. Some were fairly recent, some were faint. I pointed to a faint mark and asked, Who’s that? My great-grandmother—her name was Harriette—stiffened. That’s your great-great-aunt Mildred, she said, and left it at that. Harriette and Mildred were sisters; I didn’t understand why Harriette didn’t want to talk about her and why she seemed abruptly annoyed, even angry.

Later, I explored the attic. It was filled with musty old clothes and children’s board games and rubber-banded stacks of playing cards. I discovered a large jar of buttons of various shapes and colors—round, square, hexagonal, ebony, mother-of-pearl. Harriette let me keep the jar. I took it home, and placed it on a shelf in my bedroom. I wondered if any of the buttons had been Mildred’s. The mystery of her remained with me.

Many years later I found out that Harriette had been furious at Mildred. Furious at her for moving to Germany, for getting involved in the resistance, for getting herself executed. The idea that Mildred had been implicated with what the Milwaukee Journal called “a Communist conspiracy” was deeply embarrassing to Harriette, whose husband, a lawyer, worked for the government in Washington. Harriette urged her siblings and other members of the family to incinerate every trace of Mildred. Her nephew remembers her saying that it was imperative that “any documentation relative to that particular era be destroyed in its entirety since the sooner that sad episode be put behind us and forgotten once and for all, the better for all concerned.” Harriette died at the age of 94, blissfully unaware that 50 years earlier, her own mother had hidden a bundle of Mildred’s letters in the attic.

My grandmother found the letters while cleaning out the attic. Shortly before she died, she gave me the letters and urged me to tell Mildred Harnack’s story. ✯

This article was published in the October 2021 issue of World War II.