Who blew the secret behind the U.S. Navy’s victory at Midway—and why?

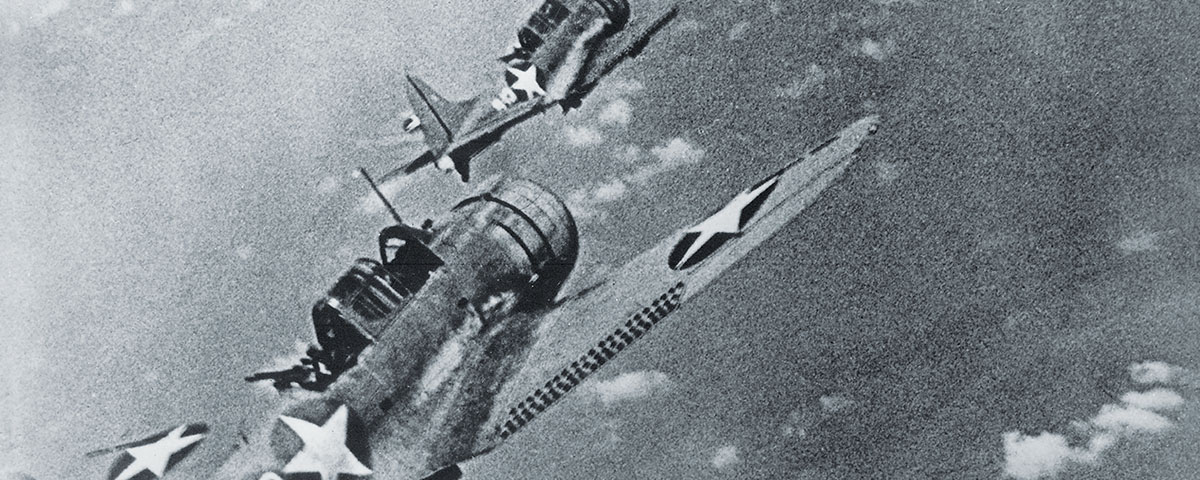

EARLY IN THE MORNING OF JUNE 7, 1942, ADMIRAL ERNEST J. KING had every reason to be pleased. He’d just received the best news of the war since he’d assumed command of the U.S. Navy, right after the disastrous Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the previous December. Three days earlier, on June 4, carrier-based warplanes of his Pacific Fleet, commanded by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, had destroyed four Japanese fleet carriers in the distant waters of the central Pacific, near Midway Atoll—the core elements of an Imperial Japanese Navy striking force—in what would soon be regarded as one of the epochal campaigns of the Pacific War: the Battle of Midway.

King had another reason to feel pleased. Nimitz’s intelligence: a supersecret unit of navy cryptanalysts based at Pearl Harbor, later known as Station Hypo, had decoded intercepted Imperial Navy messages. From Hypo, Nimitz had learned the strength and makeup of most Japanese forces advancing on Midway, including the names of key warships arrayed to attack the remote coral atoll.

Later that morning, however, as King sat reading a story in Sunday’s Washington Times-Herald in his large, no-frills office on the third deck of the old Navy Department, his mood darkened and he suddenly exploded in anger. The story that distressed him, as it turned out, was also on the front page of the Chicago Tribune, under the headline “Navy Had Word of Jap Plan to Strike at Sea.”

The headline was bad enough. Even more infuriating, the identical content of the two stories paralleled almost precisely a secret radiogram that Nimitz had sent to King eight days earlier. Circulated to only a handful of senior officers, that information was now prominently displayed in two major newspapers. The stories contained the same list of ships in Nimitz’s May 31 dispatch, and in roughly the same order. It seemed clear to King that somehow, somewhere, there had been a horrendous, potentially catastrophic leak.

King, who liked to be called COMINCH (for commander in chief), assembled his top aides to assess the damage. Most of them held the same view: While the article didn’t explicitly state that U.S. Navy code breakers had cracked the Imperial Navy’s cryptographic system, it nevertheless implied as much. King and his staff believed the leak would eventually find its way to the Japanese and cause them to change their naval code—a development that could set back U.S. code breakers many years. Nimitz’s capabilities would be weakened, his drive against Japanese naval forces slowed, and the war in the Pacific Theater grimly prolonged.

BUT IF THAT MUCH SEEMED CLEAR, MORE WAS NOT: Where did the story come from, and who leaked the information in it? Who wrote the story? (Both papers had printed the story without a byline.) There were what appeared to be vital clues to the first two questions. For starters, the Tribune’s version of the story carried a Washington dateline, suggesting that it had originated in the nation’s capital. And both versions of the story attributed the information disclosed to “reliable sources in Naval Intelligence,” suggesting that the leaker resided in King’s own bailiwick. Suspicion fell immediately on the Office of Naval Intelligence.

King’s people wanted to talk first to Commander Arthur McCollum, the chief of the Far Eastern Section of the Office of Naval Intelligence. (“I came down to the Navy Department,” McCollum would later recall, “and my goodness, the place was shaking.”) He was told to report right away to King’s chief of war planning, Rear Admiral Charles M. “Savvy” Cooke Jr. As he entered Cooke’s office, McCollum was immediately bombarded with questions: “Who do you know on the Chicago Tribune?” McCollum replied that he did not know anyone at that newspaper. Cooke wasn’t satisfied: “Mac, you’ve been talking to reporters some damn place.” Then he flashed a copy of the Tribune’s front page at McCollum and barked, “What do you think of that?”

McCollum, however, cleared himself when he compared the wording of the Trib article with his own “bootlegged” copy of Nimitz’s dispatch—a raw copy with all the “mistakes and garbles,” to use his description, that routinely turn up in dispatches and are usually corrected by radio officers on the receiving end. In juxtaposing the unedited dispatch with the article, McCollum found the same “mistakes and garbles” in both. “The names of the ships were misspelled in the dispatch and they were misspelled the same way in the paper,” McCollum told King and Cooke. He reasoned that whoever wrote the Tribune story had seen the original, unedited dispatch. If so, he could not have gotten it from the Navy Department, because copies in its files had been cleaned up and corrected. “This reporter had obviously seen that specific dispatch, and he wasn’t here in Washington,” McCollum told the two admirals.

This calmed King, but Cooke was still fuming. He was adamant that action should be taken against the Chicago Tribune and its publisher, Robert R. McCormick. “He’s a goddamned traitor, that’s what he is,” Cooke said. “The president is buying this thing and we’re going to hang this guy higher than Haman.”

Cooke was right about the president. Franklin Roosevelt and McCormick had been bitter antagonists for years. Tribune editorials during the 1930s had depicted FDR’s New Deal as a giant conspiracy to subvert “the American way of life.” As the world moved toward war in the late 1930s, the Tribune backed the America First movement, rejecting any form of intervention in Europe or Asia, and characterized FDR as a nervous charlatan “hell bent for war.” The rift deepened in 1940 after Roosevelt nominated Frank Knox to be secretary of the navy. Knox was publisher of the Chicago Daily News, the Tribune’s rival. Even though both McCormick and Knox were Republicans, strong conservatives, and ardent patriots, they detested each other. The Tribune frequently denounced Knox, accusing him, among other things, of using his government position to benefit the Daily News.

By June 1942 there was very little McCormick could put in his paper that would shock the president. But the June 7 story seemed to go too far. It’s not known whether Roosevelt actually read the story and instantly grasped its significance or Knox or some other navy official briefed him on it. But it is indisputable that the story left Roosevelt boiling mad. According to at least one account, FDR briefly contemplated sending a detachment of marines to Chicago to occupy the Tribune Tower and close the newspaper—a constitutionally suspect action that, if proposed, was quickly deflected by cooler heads. Marines or no marines, before the day ended, FDR set in motion a White House–backed campaign geared not only to silence McCormick but also to put him behind bars. Navy officials, however, quickly realized that such an effort would do nothing to help them find out how the Tribune had obtained a copy of Nimitz’s dispatch and how its article had gotten past military censors.

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, FDR had put in place two systems of censorship—civilian and military—aimed at blocking the flow of any material that might help the enemy. The Office of Censorship, set up in December 1941, published a five-page Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press that described eight categories of information to avoid: troops, ships, planes, fortifications, production, weather, photographs, and maps. The code applied only to U.S.-based reporters working inside the country. The office had no enforcement powers; it could only exercise moral pressure to bring journalists into compliance. Editors in doubt about the advisability of printing a certain story were urged to ask the government’s censors in Washington for guidance.

But for war correspondents, censorship was mandatory in combat zones. A correspondent seeking to ride with the Pacific Fleet, for example, had to sign a pledge to submit all of his stories to a navy censor. The censor might be a designated officer aboard the journalist’s ship. If no such officer was available, the writer’s copy would be routed to the Pacific Fleet’s Office of Public Relations at Pearl Harbor. In certain instances copy would be shipped directly to the Navy Department in Washington for review.

Navy officials assumed that the mystery correspondent was based in the Pacific. If the writer was indeed overseas, the story would not have come under the jurisdiction of the Office of Censorship; the appropriate censor would have been the navy itself. King’s people got in touch with Captain Leland P. Lovette in the navy’s Washington PR office, charged with censorship duties. Lovette quickly established that his office had neither reviewed nor even received any copy from the Chicago Tribune concerning Midway. He did, however, have a 3,500-word article by Tribune correspondent Stanley Johnston, describing his experience on the carrier USS Lexington when it was hit in the May 7–8 Battle of the Coral Sea. Johnston seemed worth checking out.

Lovette’s assistant, Commander Robert W. Berry, called Lieutenant Commander Waldo Drake at Pearl Harbor, where Drake directed the Fleet’s PR office. Yes, Drake knew Johnston. He filled in a few key details for Berry: Johnston, an Australian, was a likable, easygoing newcomer. He’d sailed out with the Lexington on April 15. His passage aboard the carrier had been smoothed by Admiral Nimitz himself, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet: On April 14 CINCPAC, as the fleet commander was called, sent Lexington’s skipper a letter introducing Johnston and asking that the ship’s crew assist the reporter in any way it could. (Nimitz apparently did so to quiet reporters’ gripes that the fleet was favoring Robert J. Casey, a reporter for Knox’s Daily News.)

Drake told Berry that Johnston had survived the carrier’s mauling on May 8 and that, in fact, he had been aboard one of the transports that conveyed Lexington’s survivors to San Diego. Drake didn’t think the navy had anything to worry about as far as Johnston was concerned. He assured Berry that Johnston had signed the obligatory Agreement for War Correspondents, which required him to submit everything he wrote while at sea to navy censors. But Drake was wrong. The aide he’d assigned to escort Johnston to the Lexington on April 15 failed to have him sign the form—a lapse that would greatly embarrass navy brass.

Lovette thought Johnston had probably written the offending Tribune article, and he so informed King’s staff. The commander of the Eleventh Naval District in San Diego provided additional details. The transport ship Barnett had arrived in port on June 2 with 1,251 survivors from Lexington’s fatal encounter with Imperial Navy warplanes. On May 19 the Barnett had picked up the survivors at Tongatabu in the Tonga Islands and headed east. The ship was nearing the U.S. mainland when, on May 31, Nimitz fired off a radiogram to Pacific Fleet commanders afloat—and King in Washington—with his highly detailed message about the composition of the Imperial Navy forces converging on Midway. Three days later the transport discharged its passengers at San Diego’s dock. Among them was Tribune war correspondent Stanley Johnston.

King deduced a few key points. Nimitz’s dispatch—later famous as Message No. 311221—was picked up by the transport ship, whose officers were not supposed to see it. (Barnett was not an addressee on the message.) Somehow the message had been decrypted and circulated among Lexington officers, one or more of whom probably passed a copy to Johnston. Arriving at San Diego on June 2, he would have had plenty of time to reach Chicago and write his story for the June 7 edition of the newspaper.

But some mysteries remained. The most glaring of them was Johnston himself. From FBI reports and navy sources, a picture of Johnston slowly emerged. Tall, outgoing, a bit garrulous, and cutting a dashing figure with his smartly trimmed mustache and Australian accent, Johnston had been a bizarre addition to the 2,951 officers and men assigned to the Lexington. Many of them were fascinated by Johnston; they liked hearing him tell the tales of his travels and adventures.

Born in New South Wales, Australia, and trained as an engineer, Johnston seemed to have been everywhere. As a young man he had slashed his way through the jungles of New Guinea to work a gold mine. Later he toured Germany with his future wife, Barbara Beck, a dancer he had met at a nightclub in New York. (Beck, born in Germany, was now a naturalized U.S. citizen.) While traveling through Germany, Johnston had raised funds to launch a business selling plastic hair curlers to German housewives.

With war looming he and Barbara repaired to Paris, where Johnston joined a news and photo transmission company, Press Wireless Inc., that made good use of his background in engineering. But the job didn’t last; while visiting London on a business trip, he was abruptly fired under murky circumstances. Using his ability to talk and to sell himself, he wangled a slot as a stringer in the London bureau of the Chicago Tribune, and the paper sent him to Dover to cover the first days of the Battle of Britain. He later reconnected with Barbara (who had been stranded for a time in Paris), and in the spring of 1941 they headed for Chicago, where he asked the Tribune to hire him. It did. In the fall he and Barbara married; a few weeks later he gained his U.S. citizenship. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the paper sent him to Hawaii to cover the Pacific War, now as a bona fide war correspondent.

STRAIGHTFORWARD AS HE SEEMED TO BE, JOHNSTON HAD NOT DISCLOSED EVERYTHING to the men on the Lexington. He had not mentioned, for example, that while working briefly in Amsterdam during his tenure with Press Wireless, he had been investigated by the Dutch Intelligence Service. “His frequent journeys from Holland to France led to the belief that he was a German intelligence agent,” FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover told Roosevelt in a blunt, hard-hitting memo. British authorities also had concerns about Johnston. They lifted his visa during his business trip to London when they learned he had falsely claimed to have been an Australian Army officer during World War I. (He had served only as a yeoman in the Royal Australian Navy Reserve.) That event led to his dismissal from Press Wireless.

But Hoover omitted some relevant information. He didn’t point out, for example, that British intelligence had cleared Johnston of suspicions that he might be a German agent. Nor did he report that, in the words of one navy officer, Johnston “behaved with conspicuous courage” during the Coral Sea battle. “He rescued at least one seriously burned and blinded man from a smoke and flame filled compartment,” wrote Morton Seligman, Lexington’s executive officer. “He was observed everywhere lending aid to the wounded….He was among the last to leave the ship.” Lex’s captain and the task force commander recommended to Nimitz that Johnston receive a citation or medal for his exemplary conduct; Nimitz endorsed the proposal and forwarded it to King in Washington for final action.

Of far greater importance to King than Johnston was how the reporter got that story: Who had leaked Message 311221? King quickly launched an internal investigation to find out. He ordered Vice Admiral John W. Greenslade, the commander of the Twelfth Naval District, to round up in one room the responsible officers of both the Lexington and the Barnett—a group that would include Seligman and Barnett’s captain, Wallace B. Phillips—and to cross-examine them on June 11 in San Francisco.

The Justice Department also wanted answers. At the behest of Attorney General Francis Biddle, Hoover ordered his agents to figure out how Message 311221 might have passed from navy hands to Johnston. Soon G-men were fanning out across the country, interviewing crew members in Boston, Denver, Honolulu, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Seattle, and other cities.

Reports started rolling in. From Greenslade’s investigation, King learned that Seligman had arranged for Lexington’s radio officers to decrypt all Pacific Fleet dispatches flowing into the Barnett, even if CINCPAC hadn’t addressed the dispatch to the Barnett. Captain Phillips was to review each CINCPAC message before letting a courier take it to Seligman and the four Lexington officers that Seligman had authorized to see such dispatches. Beginning with Seligman, the watch officer was to make his rounds through the ship to those authorized officers, secure the initials of each, then return the message to a safe in the radio room. He was not to let the dispatch out of his sight.

The plan didn’t work quite as smoothly as Seligman and Phillips intended. Seligman occupied a spacious three-room suite normally reserved for high-ranking guests. In addition to Seligman’s quarters, the suite had a dining room with a large table and an extra bedroom with two bunks; Seligman reserved one for a seriously ill officer needing bed rest and the other for the amiable journalist he had come to trust: Stanley Johnston. Each day Seligman’s stateroom filled with officers coming by to sit at Seligman’s table, drink coffee, and catch up on the latest news. Johnston was always there, too. Into this bustling mix a Lex radio officer would show up each day with a folder containing that day’s CINCPAC messages. Seligman recognized that his men would benefit from hearing these updates, and he might read aloud from a dispatch, or if he thought a message particularly interesting, he might pass it around. This broke the rules, but the radio officer couldn’t do much about it. Seligman outranked him.

During the entire voyage, from the time he boarded the ship at Tongatabu, Seligman had not been well. He had been severely banged up during the Coral Sea attack. Rescuing a sailor, he got caught in an explosion; he remained weak and, he admitted later, “a little confused.” He would later say that he didn’t remember seeing Message 311221 when it was delivered to his table late in the afternoon of May 31. He didn’t deny getting it—in fact he couldn’t, as his initials were on it—but he said the dispatch made no impression on him.

Others in Seligman’s suite that afternoon had a better memory. One remembered Seligman reading aloud from the message; another was pretty sure that he had made a few notations from it. When Seligman finished, the courier, Lieutenant F. C. Brewer, continued his rounds.

Always busy after dinner, Seligman’s cabin had teemed that evening. Some of those present were “authorized” officers whom Brewer had already visited; others had heard about Nimitz’s extraordinary message and wanted to learn more. When Lieutenant Commanders Edward J. O’Donnell and Edward H. Eldredge arrived, they noticed on Seligman’s table a handwritten outline that itemized the composition of various Imperial Navy forces. It was written in pencil on a blue-lined piece of scratch paper. Another guest, dive-bomber pilot Robert Dixon, wasn’t a department head and thus was not authorized to see dispatches. But Dixon did read what was on the paper and then handed it to O’Donnell, who was authorized and recognized it as similar to the dispatch Brewer had brought to his quarters that afternoon: Message 311221. The scrap listed the names of the same 12 Japanese ships, divided into three groups: a striking force, a support force, and an occupation force. O’Donnell knew where the list on the scratch paper came from.

Dixon, who was renowned for his exploits at the Coral Sea, didn’t like the scene in Seligman’s suite. He felt uneasy seeing a document of such obvious gravity being passed around so casually. And he was troubled by Johnston’s presence in the room. But he later told FBI agents that he didn’t see Johnston copying Nimitz’s message; apparently, no one did. (Dixon may have seen more than he told the agents, however: Years later he told Robert Mason, the editor of the Virginian-Pilot, Norfolk’s morning newspaper, that he had spotted Johnston taking notes from the Midway plan.) As did O’Donnell and Eldredge, Dixon told agents that he’d lost track of Seligman’s much-handled scratch paper. The piece of paper, apparently, had simply vanished.

KING THOUGHT JOHNSTON OUGHT TO BE QUESTIONED. He directed his chief of staff, Vice Admiral Russell Willson, to contact the Tribune’s Washington bureau chief, Arthur Henning, to arrange a meeting. Realizing trouble was brewing, Henning rang up McCormick in Chicago and passed on Willson’s request. McCormick, more irritated than worried, reached the Trib’s managing editor, J. Loy “Pat” Maloney, and told him to order Johnston to come to Willson’s office first thing the next morning. McCormick wanted peace with the navy.

Bleary-eyed and dog-tired, after hours of all-night travel, first by plane to New York, then by train to Washington, Johnston managed to dumbfound the admirals that King had assembled to hear his story. With their shoulder boards in full array, they were a formidable group, consisting, most notably, of Admiral Arthur J. Hepburn, director of public relations (responsible for censorship); Vice Admiral Theodore S. “Ping” Wilkinson, director of intelligence; and Willson. Willson did most of the questioning. Did Johnston not understand, Willson wanted to know, that the pledge he signed at Pearl Harbor obligated him to submit to navy censorship? Johnston stunned the admirals by claiming that he had gladly observed navy censorship even though he was not obligated to do so: No one, he said, had asked him sign a censorship pledge. Although Johnston knew what he was talking about this time, the navy chieftains scoffed. They also challenged his next assertion: that he had based his story not on a copy of Nimitz’s secret dispatch but on his knowledge of Jane’s Fighting Ships, a widely available reference book. When Johnston couldn’t explain why the ships cited in his article almost exactly matched those in Nimitz’s 311221, the admirals rolled their eyes. Willson then ended the meeting and led Johnston to the door.

But the Trib’s Henning alerted Johnston that Willson was “not satisfied” with his story, so Johnston returned to the admiral’s office late that afternoon. Willson was alone this time. The only record of this second meeting is a memo that Johnston prepared for his Tribune bosses. He now told a very different story: He admitted that he had seen some kind of list of Imperial Navy warships. As Johnston explained it, he came across the list accidentally, late in the evening of June 2, just after the Barnett had docked in San Diego. “I was using the typewriter to clean up my stories and on moving some old papers from my desk saw a piece of paper with light blue lines on which someone had written the names of Japanese warships and listed transports, etc., under headings of ‘striking force,’ ‘occupation force,’ and ‘support force.’” Then he added a kicker: “I copied the names off the list.”

A clean copy of his notes secure in his lapel pocket (he had typed them up in his hotel room that night), Johnston proceeded to Chicago. He was in the Tribune newsroom on Saturday night, June 6, writing articles about the Battle of the Coral Sea. The Associated Press teletype was clacking over in one corner; Johnston took a look. The machine was printing out a communiqué issued by the Pacific Fleet commander, Admiral Nimitz. It read, in part: “Through the skill and devotion to duty of their armed forces of all branches in the Midway area our citizens can now rejoice that a momentous victory is in the making….Pearl Harbor has now been partially avenged.” Johnston said he was elated by the news, and he remembered the notes in his pocket. He showed them to the managing editor, Pat Maloney, calling them “good dope” on the vanquished Japanese force at Midway. “This is fine; this is great,” Maloney would later recall telling Johnston. “It shows what a helluva force the American Navy whipped out there.”

With the paper’s deadline fast approaching, Maloney teamed Johnston with the paper’s aviation editor, Wayne Thomis, a faster—and, from Maloney’s point of view, better—writer. Thomis shaped Johnston’s memo into an article while Johnston thumbed through Jane’s Fighting Ships, digging out key details about the Japanese warships. Thomis made a critical change in Johnston’s memo: “I’m the stupid jerk who attributed the story to naval intelligence,” he ruefully admitted later.

Maloney didn’t like the story Thomis handed him; he rewrote the first two paragraphs but left intact Thomis’s unique contribution. He also made a controversial change of his own: He slapped a Washington dateline on the article, making it appear as if the facts originated at the Navy Department. The story was ready to go.

Maloney knew he had one more hurdle to clear: censorship. He reread the guidelines on ships in The Code of Wartime Practices published by the civilian Office of Censorship. It forbade printing the location of U.S. ships in U.S. waters as well as the location of enemy vessels in or near U.S. waters. Maloney relaxed; Johnston’s story didn’t disclose the movements of U.S. naval vessels or enemy ships in or near U.S. waters. To be on the safe side, Maloney called Henning in Washington for advice, describing Johnston’s story as some “information and dope” on the makeup of the Japanese force at Midway that his reporter had brought back from the West Coast. Would he be in the wrong to run this story? Henning told Maloney that he didn’t think so, as the story wouldn’t be telling the Japanese anything they didn’t already know.

Secure in the belief that this story fell outside the Office of Censorship’s guidelines, Maloney didn’t bother to check directly with the censors. He moved the story ahead, not realizing that Henning had led him astray. He had also led himself astray. The censorship guidelines, as it happened, didn’t apply to work done by correspondents in combat zones. Johnston had been with the fleet in a combat zone; navy censors, not the staff at the censorship office, had jurisdiction over his story. The Trib story brazenly flouted the government’s rules for reporting military information.

BUT HAD THE NEWSPAPER COMMITTED A CRIMINAL ACT? Had it violated federal law? President Roosevelt thought so. So did Navy Secretary Knox. On June 9, in a letter to Attorney General Biddle, Knox recommended that “immediate action” be taken to obtain indictments under the Espionage Act of 1917 against Johnston, Maloney, and other individuals involved in the publication of the Tribune’s June 7 story. Knox alleged that Johnson, lawfully or unlawfully, had come into possession of “secret and confidential information pertaining to the national defense” and communicated it to his publisher, who then disclosed it to the world. Knox alleged that Johnston had violated clause (d) of section 31, Title 50, of the Espionage Act. The clause did not require the government to prove that Johnston intended to reveal secret information, just that he had done so. If convicted, Johnston could be imprisoned up to 10 years and fined up to $10,000.

Two months later, on August 7, Biddle announced that he had ordered a grand jury in Chicago to investigate the publication by “certain newspapers” on June 7, 1942, of confidential information concerning the Battle of Midway. The probe marked the first (and, it would turn out, the only) time in U.S. history that the Department of Justice had sought to prosecute a major newspaper for violating the Espionage Act by printing leaked classified information. News soon leaked that Biddle’s target was the Chicago Tribune and two of its editorial staffers: Johnston and Maloney. Biddle recruited William D. Mitchell, a prominent New York lawyer and attorney general under President Herbert Hoover, to oversee the case. A week later, on August 13, Mitchell started taking testimony from witnesses. Over the next four working days he presented 12 witnesses to jurors: seven navy officers familiar with Johnston’s activities aboard Lexington and Barnett and five journalists, two of whom represented the New York Daily News and Washington Times-Herald. (Both had run the Tribune story, distributed by the Chicago Tribune News Service.)

On August 19 the jurors made headlines: They threw out the case, giving no reason for their action. Oddly, their decision didn’t stem from testimony they had heard; it resulted primarily from witnesses they had not been permitted to hear. The central pillar of the government’s case was to be testimony from expert witnesses—navy cryptanalysts based in Washington—who would explain the extreme sensitivity of the material in the Tribune article, and detail why, if it was widely circulated, it would do irreparable damage to U.S. national security. Knox had promised Biddle and Mitchell that the witnesses would be in Chicago on August 19 to lay out the case, but they didn’t appear. Knox held them back at the last minute at the stern insistence of Admiral King, who, seeing the matter more clearly than he had earlier, now claimed the witnesses would do the war effort more harm than good.

Jurors were astounded. They were being asked to indict Johnston and Maloney without being told what crime the men had committed or why it mattered. They decided that no indictment be returned against either Johnston or Maloney, or the Tribune itself.

Mitchell faulted Knox for the debacle, but Knox’s explanation was sensible. “The truth was that we had just again successfully broken the Japanese code and this fact was of immense value to us in operations then in progress,” Knox informed Mitchell later. “Naturally, this made the military and the Navy extremely apprehensive lest any talk of code-breaking in the newspapers in the United States lead the enemy to take action to cut off this highly valuable source of information.” The implications of Knox’s defense were stunning: The Imperial Navy hadn’t changed its main code. Consequently, the Tribune story hadn’t damaged national security at all.

ROBERT McCORMICK HAD DEFENDED JOHNSTON AND MALONEY vigorously during their weeks in the government’s cross-hairs. With the grand jury case scuttled, he welcomed them back. Maloney returned as managing editor, and Johnston found a permanent place in the Tribune family. Johnston never did receive the decoration endorsed by Nimitz; King saw to that. Nor did he get back his navy press credentials, which had been revoked by navy PR officials. Without a press pass he couldn’t cover the war from either the Pacific or European fronts, and he never again set foot in a combat zone. But the Tribune’s editors did find ways to employ him usefully in the years ahead.

Johnston’s duties changed in the early 1950s when, at the behest of the ailing Tribune publisher, he and Barbara moved into McCormick’s mansion at Cantigny Park, 30 miles west of Chicago. After McCormick died in 1955 at age 74, Johnston was made general manager of the 500-acre estate. When he died of a heart attack in 1962, the Tribune’s obituary celebrated its onetime war correspondent. Fittingly, the obit was written by Wayne Thomis. “Stanley Johnston led a fabulous life,” Thomis wrote. “Few men have combined so much adventure, travel, and danger in their lives and yet retained a zest for living.”

Johnston may have died a hero at the Chicago Tribune, but he was not regarded that way, then or later, at the Navy Department—or, for that matter, any of the government’s security agencies, where a bitterness toward Johnston lingered for years. Revisiting the Johnston affair 50 years later, a National Security Agency historian could write in 1993 that the correspondent had, “with the help or negligence of others, betrayed the trust placed in him”—trust placed in him by the officers and men who had befriended and assisted him aboard the carrier Lexington.

The animus toward Johnston stemmed primarily from some nagging what-ifs: What if his article on the front page of the June 7, 1942, Chicago Tribune had indeed been seen by the high command of the Imperial Japanese Navy? What if the Japanese officers reading this story had drawn the obvious conclusion: that America’s navy had cracked their main operational code, the famed JN25? And what if the Japanese navy had directly abandoned JN25 for an altogether new crypto system—as some U.S. Navy and government officials thought they would do? What would have been the consequences for the U.S. war effort?

The repercussions of a leak of this magnitude, revealing the U.S. Navy’s success against Japanese naval codes, can be glimpsed through General George Marshall’s secret letter to New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey in 1944, when Dewey was running for president against Franklin Roosevelt. Learning that Dewey was getting ready to disclose that FDR, thanks to code breaking, supposedly had gained insight into Japanese intentions before Pearl Harbor, Marshall informed the governor of the potentially disastrous effects of this contemplated revelation.

Recalling the battles at Coral Sea and Midway, Marshall told Dewey that operations in the Pacific continued to be guided by knowledge acquired through code breaking. He warned of “utterly tragic consequences” for the campaigns in both Europe and the Pacific if the Germans or Japanese suspected this source of America’s information. “[T]hese intercepted codes,” Marshall wrote, “contribute greatly to the victory and to the saving in American lives, both in the conduct of current operations and in looking towards the early termination of the war.”

Dewey did not give the speech that Marshall feared would cost American lives. What, then, possessed Johnston and Maloney to put in the Chicago Tribune an article that, under certain circumstances, could have had the same disastrous consequences? In his case against them, Mitchell didn’t suggest that they actually intended to harm U.S. security or endanger American lives. “Nobody is charging you with that,” an exasperated Mitchell told Maloney during an interview on July 9, 1942. “I would say, if you want my judgment about it: I think you had a scoop on some vital information that Nimitz had not disclosed, and nobody else had disclosed, and at midnight you had this thing handed to you and you realized it was such a scoop that you were crazy to publish it.” Seventy-five years after this potentially calamitous leak, no historian has better explained the motives of the two journalists: They wanted a scoop.

No one was ever punished for this leak of top-secret navy code breaking. As Maloney carried on as managing editor of the Tribune, Johnston spent his last years overseeing Cantigny Park and indulging his horticultural hobbies. (He developed a prize-winning rose he called Chicago Peace.) The only loser in the Johnston affair was Morton Seligman. Admiral King blamed Seligman for failing to safeguard the secret CINCPAC messages that flowed into the Barnett and told Nimitz that he was putting Seligman’s career in “escrow.” Whether it was because of King or, more likely, because of the severe injuries he sustained at the Coral Sea, Seligman never again served in a combat zone. He retired from the navy in 1944.

In the wake of Stanley Johnston’s scoop, the U.S. Navy caught a break. Despite the fears of King, Cooke, and others, the Imperial Japanese Navy never changed its main code. It modified this code from time to time (it did so, agonizingly, shortly after the Tribune leak), but it never discarded its basic JN25 system. The Japanese navy began the war with JN25(B); by the end of the war, it had reached JN25(P). How could the Japanese have missed this sensational leak? Happily for all concerned, as King’s biographer, Thomas Buell, mused, “the Japanese apparently did not read American newspapers.” MHQ

ELLIOT CARLSON is the author of Joe Rochefort’s War: The Odyssey of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway (Naval Institute Press, 2011), for which he was awarded the Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature. His new book, Stanley Johnston’s Blunder: The Reporter Who Spilled the Secret Behind the U.S. Navy’s Victory at Midway, from which this article is adapted, will be published in October 2017 by the Naval Institute Press.

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Midway Betrayal

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!