By 1975, when President Gerald Ford forced William Colby to resign as CIA director, the 55-year-old spy had spent his life fighting clandestine battles.

At 21 he joined the OSS, studied T. E. Lawrence, led sabotage missions behind Nazi lines in Norway and France, and was awarded a Silver Star. As postwar Italy’s undercover CIA station head, he funneled millions in cash to the Christian Democratic party and its Vatican allies, helping to defeat the country’s heavily favored Communist Party in the 1948 elections. In early 1960s Vietnam, he fostered “strategic hamlets,” a model for General David Petraeus’s most recent counterinsurgency plans. Later he oversaw the Phoenix Program, which relied on torture and assassination to “root out” Vietcong.

After Watergate, Colby faced angry Congressional oversight committees; he cooperated more than Ford, Henry Kissinger, and Donald Rumsfeld wanted and was axed. In 1996, he went canoeing solo on a river in southern Maryland; nine days later, his body washed up on shore. Speculation ran wild, but his death was ruled an accidental drowning.

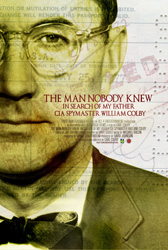

Directed by Colby’s son Carl, The Man Nobody Knew is a probing, controversial, and often wrenching documentary. Colby’s family and colleagues—he had no friends—join historians and journalists to grapple with what the wiry Clark Kent lookalike did and why. The 2011 movie unravels the spy’s tangled webs, yielding new insights, but the man was so secretive that he shut out even his loyal wife, Barbara: She learned he joined the CIA from his carpool mates. Barbara maintains he had “an internal moral compass.” Others such as Bob Kerrey, Bob Woodward, and Daniel Schorr aren’t so sure. Carl Colby contends that guilt—over Vietnam and neglecting the family, especially an epileptic daughter—drove his dad to suicide. Other Colbys strongly disagree.

Family life forms an ironic, often poignant counterpoint to larger events: Colby’s children playing with the Italian prime minister’s children in 1950s postwar Rome as the city springs back to life; the languid ease of early 1960s Saigon, where French was everyone’s lingua franca; a vacation trip to France, where Colby shows Carl a ditch, happily recalling two wartime days he hid there.

“He was a soldier who loved the fight,”?Carl recalls. “He was the coolest man I knew. But he wasn’t really there for us. I’m not sure he loved anyone.”

Although simple closure eludes the son, his thoughtfully paced, visually compelling movie sheds complex and fascinating light on his spymaster-father’s worlds.

Gene Santoro is a New York–based writer and reviewer.