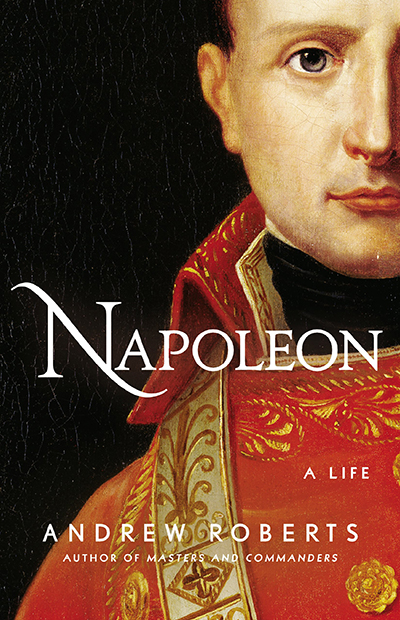

Napoleon

A Life

by Andrew Roberts. 976 pages.Viking, 2014. $45.

Reviewed by Rafe Blaufarb

We are fast approaching 2015, the bicentennial of Waterloo. This has stimulated an outpouring of writings not only on the battle itself but also on its central figure, Napoleon. Academics such as Michael Broers and Philip Dwyer have been quick to get into the game, but so have more commercial writers. In this latter category and well above his peers is Andrew Roberts. Roberts is a gifted author with a long list of military history bestsellers to his name. His latest effort, Napoleon: A Life, is a joy to read—a serious work based on a comprehensive grasp of Napoleonic scholarship, archival research, and dozens of battlefield walks.

The book seeks to present a balanced picture of Napoleon, which is not as simple as it seems, for Napoleon is a deeply polarizing figure. Indeed, Roberts confides that being English by birth and education meant he was raised on the black legend of Napoleon. This is common in Britain, the land of Nelson and Wellington. (Wellington nonetheless admired Napoleon to such a degree that he had an 11-foot-tall nude statue of the emperor on display in his London home.) To Roberts’s credit, he does not go too far in the other direction; he skillfully presents the good and the bad that Napoleon was responsible for. Napoleon was only able to impose progressive civil reforms, such as the Napoleonic Code and religious tolerance, because he had vanquished—with a great deal of force—the conservative European powers opposed to him. Accordingly, Roberts devotes much attention to Napoleon’s military exploits.

Perhaps three-quarters of the book deals with military history and Napoleon as general. Roberts provides fine accounts of his main battles, as well as analysis of his famous principles of war (including occupying the central position and concentrating overwhelming force at the enemy’s critical point). There are also concise descriptions of Napoleon’s operational methods, such as his use of the bataillon carrée to maneuver groups of army corps rapidly over great distances while preserving their capacity for mutual support. But Roberts does more than just elucidate (with great flair) these well-known aspects of Napoleon’s generalship. He also brings to light more obscure ingredients of his military success. These include his extensive use of intelligence and, most important, his unparalleled ability to compartmentalize, both mentally and physically. Thus, he poured out a daily stream of love letters to Josephine while orchestrating the First Italian Campaign, a magnificent feat of generalship still studied at West Point. Napoleon could nap at will, even next to roaring cannons, waking up after just 10 minutes completely refreshed and in time for the decisive battle.

While changes in technology and the nature of war have rendered many of the operational and tactical dimensions of Napoleon’s art of generalship of dubious relevance, his rigorous control over his physical and mental state has been widely emulated by, among others, Bernard Law Montgomery in World War II. That quality remains just as critical to military leadership as ever.

Rafe Blaufarb is the Ben Weider Eminent Scholar and director of the Institute on Napoleon and the French Revolution at Florida State University’s department of history.

MORE WINTER 2015 REVIEWS

.jpg)