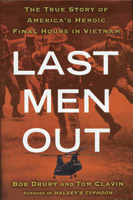

Last Men Out

The True Story of America’s Heroic Final Hours in Vietnam

By Bob Drury and Tom Clavin. 294 pp.

Free Press, 2011. $26.

Reviewed by David Lamb

Given all the books published about Vietnam, one might think the subject had been milked dry. But Bob Drury and Tom Clavin disprove that assumption with this riveting new book, which chronicles the final hours before Saigon fell to North Vietnamese troops. It is a story of fear, pandemonium, betrayal, and courage, told through the perspective of the U.S. military personnel on the ground.

The helicopter evacuation—the largest in history—of Americans and South Vietnamese from Saigon on April 29, 1975, began with a prearranged signal from Armed Forces Radio: the words “The temperature in Saigon is 105 and rising,” followed by a Bing Crosby recording of “White Christmas.” With 150,000 North Vietnamese troops encircling Saigon and artillery pounding Tan Son Nhut airport, panic and chaos gripped the capital. Surly soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, feeling betrayed by the American withdrawal, roamed the streets. Mobs of civilians, fearful that a bloodbath would follow a communist takeover, stormed the U.S. Embassy looking for a way out of Vietnam.

This isn’t a book about policy and diplomacy. It’s a view from ground level

Drawing on declassified military documents and dozens of interviews, the authors provide an authoritative, hour-by-hour narrative of an event that will live forever in American history. This isn’t a book about policy and diplomacy. It’s a view from ground level: the American ambassador, Graham Martin, refusing to acknowledge the end had come even as North Vietnamese tanks roll up to the outskirts of Saigon; the 11 Marines trapped on the roof of the embassy, preparing to fight but praying for their evacuation chopper; the heartbreak of leaving behind hundreds of South Vietnamese who had worked for the United States and would face great danger under a communist regime.

In one of the book’s most dramatic scenes, the Marine security guards lose control of a disorderly crowd of thousands packed onto embassy grounds. Corporal Steve Schuller, a New England farm boy, turns in time to see a South Vietnamese soldier lunge at him with a bayonet. He feels the steel point glide between his ribs. Get a medic, someone shouts. “No way.

I go out with everyone else,” Schuller says, then tears a strip from his dirty T-shirt and plugs it into the wound with the cap of his canteen.

Throughout the eight-hour operation, the Marine and air force helicopters made more than 600 flights in and out of Saigon and managed to extract some 7,000 Americans, Vietnamese, and third-country nationals. No helicopters were shot down and the Marines suffered no casualties.

The Americans, Drury and Clavin write, had no idea at the time that NVA commanding general Van Tien Dung had decided, with the approval of the Politburo in Hanoi, not to interfere with the U.S. withdrawal. He had set a deadline of dawn April 30. After that, he was prepared to launch a full-scale assault on Saigon. The Marines beat the deadline with just hours to spare.

I had been in Vietnam that April reporting for the Los Angeles Times, and flew out of Saigon on the last commercial flight. Flying over the South China Sea, I remembered what Ho Chi Minh, speaking indirectly to the United States, had said in the mid-1960s: “We will spread a red carpet for you to leave Vietnam. And when the war is over, you are welcome to come back because you have technology and we will need your help.”

Vietnam’s revolutionary leader died of natural causes six years before the Saigon evacuation. But reading how the United States averted potential disaster and pulled off the operation without a single casualty, I can’t help but wonder if the Americans didn’t leave on Ho’s red carpet.

David Lamb spent six years in Vietnam as a journalist. He is the author of Vietnam, Now: A Reporter Returns (2003).