Construire un autre Paris? Non, c’est impossible!

BUT BUILD A SECOND PARIS they did, in one of the oddest episodes of World War I. The project was set in motion by the French Ministry of War as a massive decoy to fool German airmen, who had begun bombing Paris seriously in early 1916. By the spring of 1917 the threat of aerial bombing had grown acute. The German Gotha G-series bombers had supplanted the more vulnerable Zeppelins and raided London for the first time, killing some 160 and injuring another 430. Growing Allied air power and increased antiaircraft firepower compelled the German bombers to switch to night attacks, when city lights were about all they had to go on for navigational reference points. In the days well before radar, let alone GPS and other such navigational aids, it was no easy matter to locate a target—even one as large as a city—after dark. Pilots found their way by following rivers and railroad tracks and watching for lights.

The City of Light was too obvious a target to resist, and Paris’s turn came one night in late January 1918. Thirty twin-engine Friedrichshafen G.III bombers—which could then carry a payload of about 600 and 1,000 kilograms of explosives—killed 26 Parisians and wounded nearly 200 others.

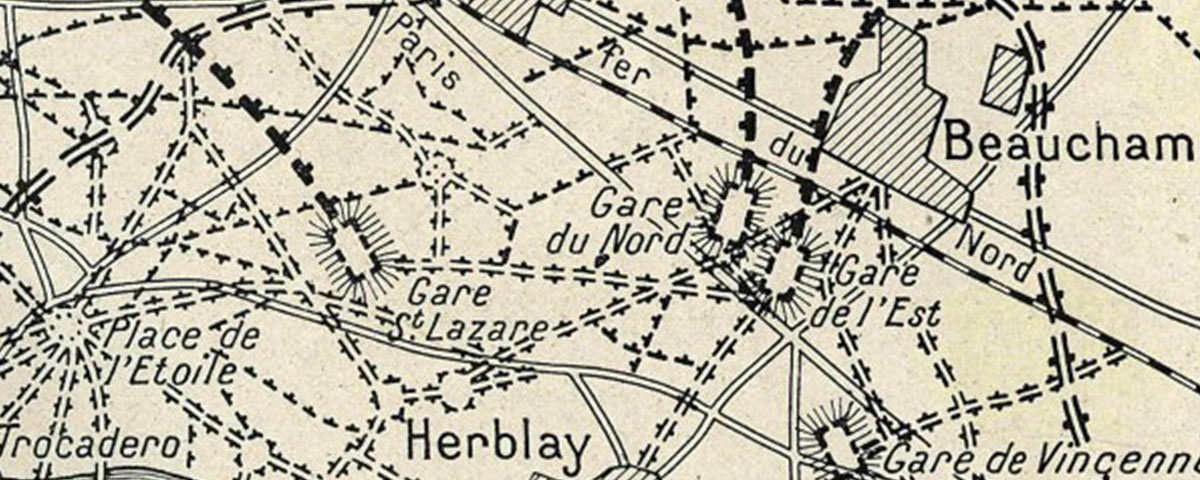

Something had to be done. It was determined that a faux Paris would be built to mimic three distinct areas in and around the city. The first area to be replicated was to resemble the northeast part of the city and the nearby industrial suburbs of Saint-Denis and Aubervilliers. It would not be a complete copy, but it would have fake roads, railways, large landmarks like the Gare du Nord and the Gare de l’Est and some very clever lighting schemes that would—from the air—look like factory buildings with dirty glass windows, traffic, railroad trains moving on tracks, and lighted urban street scenes. The site chosen for this first replica was near the town of Maisons-Lafitte, some 15 miles north of Paris in a loop in the Seine that resembled the loop in which the real city was situated.

PLANNING WAS EXTENSIVE, and of course secret. An Italian-born engineer named Fernand Jacopozzi was placed in charge of drawing up plans for the fake city and of developing the deceptive lighting (after the war, he was admitted to the Legion of Honor, though, because of continued secrecy, few people knew why he was so honored). His faux Paris was built to be bombed, with buildings and other structures of wood and painted canvas and an elaborate electrical grid for the lighting. It was well under way but not completed when the armistice ended the war in November 1918, so it was never tested for real-life effectiveness. Instead, it was quickly destroyed—not by German airmen but by the French authorities who had conceived and built it.

The faux Paris secret held until November 1920, when the Illustrated London News ran a feature story on the whole deception, complete with pictures. The site of Paris II was built over soon after the war, and no trace of the decoy city now remains.

.jpg)