Just beyond the Old Post Chapel entrance gate at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Va., stands an obelisk headstone bearing a detailed yet spartan inscription:

Commissioned surgeon of colored volunteers, April 4, 1863, with rank of Major. Commissioned regimental surgeon of the 7, Regiment U.S. Colored Troops, October 2, 1863. Brevetted Lieutenant Colonel U.S. Volunteers, March 13, 1865, “For Faithful and Meritorious Services.”

Beneath these impressive credentials—chiseled in bold letters—is the name AUGUSTA. To know the life, times, and military career of the man buried here is to better understand why Americans fought a civil war.

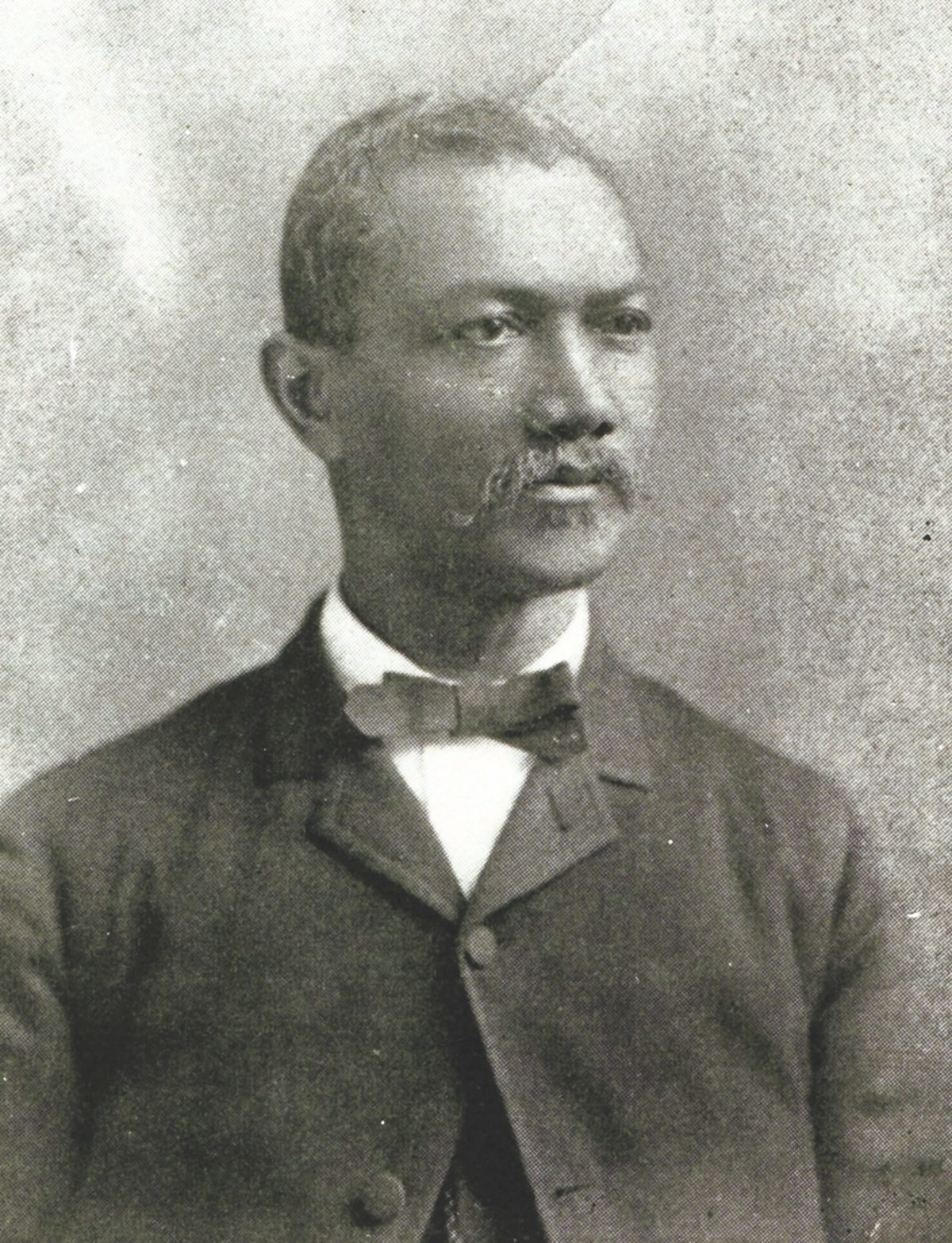

Alexander Thomas Augusta was born in 1825 to so-called “free persons of color” in Norfolk, Va. A naturally intelligent boy, he was curious about the world, hungry for knowledge and improvement, and, most important, driven by an unstoppable spirit.

But Augusta lived in an age of slavery and slave uprisings. He was six years old when Nat Turner staged his violent rebellion against slaveowners in nearby Southampton County, killing up to 65 people, 51 of whom were White. From then on, suspicion and distrust reigned over the Black community—free and enslaved.

Whites did everything in their power to keep Blacks from organizing, including efforts to hold them back intellectually. To teach a person of color how to read, for example, was a serious offense and, from the slaveholding perspective, an imminent threat to life and property.

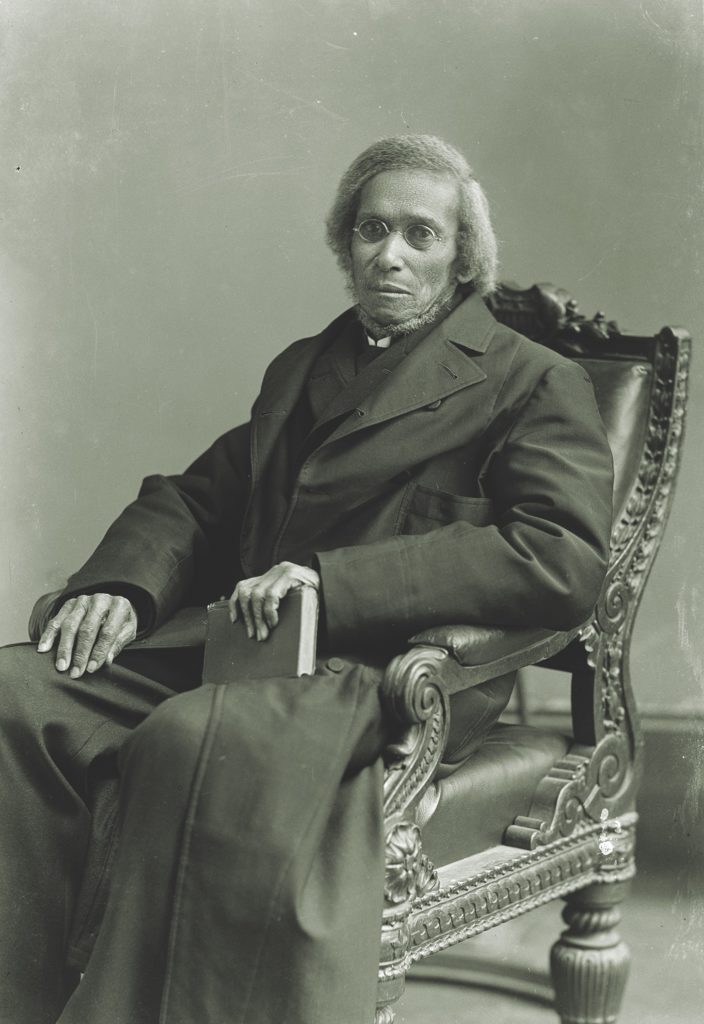

Augusta, however, vigorously pursued his ambitions; one of them was reading. While in his late teens, he secretly learned to do so with the help of Daniel Payne, who later became both a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the president of Ohio’s Wilberforce University.

Augusta read anything he could find. And although he was omnivorous when it came to subject matter, he nevertheless had a favorite topic—medicine.

Increasingly well read, Augusta set out for Baltimore, Md., in 1847. Here, he settled down temporarily, and always with an eye toward doing more than reading. What he had in mind was virtually out of the question for a Black man in mid–19th century America.

Shortly after landing in Baltimore, Augusta moved to Philadelphia with hopes of studying medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Sadly, in his attempt at admission, he met with his first taste of the institutionalized prejudice that was quickly becoming a cancer to the Union.

According to some sources, the school denied his application because he was “inadequately” prepared for the curriculum. The reality of circumstances, however, skews more in the direction of skin color and the unsavory notion of a Black man transcending the boundaries of his designated position in society.

But Augusta would have none of it, and, following a brief stint of tutelage under the guidance of a professor at the university, returned to Baltimore, married, and around 1850, went to California, where he worked as a barber in the midst of the booming Gold Rush. By most accounts, Augusta was saving money to finance his next move, which took him and his wife to Toronto, Canada.

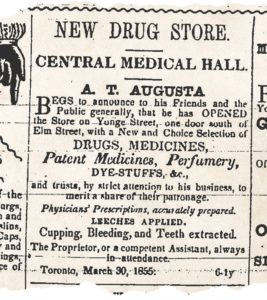

Shortly after his arrival, Augusta enrolled as a medical student at the University of Toronto’s Trinity College. For the next six years, he endured the rigors of medical school, meanwhile working side jobs as a chemist and pharmacist, selling, as one advertisement announced, “Patent Medicines, Perfumery, Dye Stuffs, etc.,” as well as services such as tooth extraction, the filling of prescriptions, and the application of leeches.

Finally, in 1856, Augusta accomplished a feat that many African Americans in his day would never have entertained, let alone successfully completed: He graduated from Trinity College with a bachelor of medicine. According to the college’s president, John McCaul, he was “one of [my] most brilliant students.”

Not surprisingly, Augusta enjoyed Toronto, which was known for its racial tolerance. Life there was normal. He could excel without swimming against the currents of racial bigotry. After his graduation, he opened a medical practice and had a fair amount of White patients. He also devoted enormous energy to activism within the local Black community.

In addition to his work as a physician, Augusta cultivated a conspicuously public presence as a champion of racial equality. He helped draft petitions against anti-Black candidates for the Canadian parliament, arranged events featuring abolitionist speakers, and served as the president of the Provincial Association for the Education and Elevation of the Coloured People of Canada.

But the safety and prosperity he found in his new home unfortunately didn’t define the world over, and it definitely didn’t match conditions for Blacks in his native land, where the election of President Abraham Lincoln had sent the country spiraling on a path to civil war.

Over the next few years, Augusta remained in Toronto reading headlines that dissolved from one seemingly earth-moving event to another: the Rebel bombardment of Fort Sumter; the Battle of Antietam; and, in 1863, President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

The latter was a turning point for thousands of African Americans, including Augusta, who saw the proclamation as a beacon of hope and a call to action. Enforced as of January 1, 1863, Lincoln’s proclamation freed the slaves and allowed for the enlistment of Black soldiers in the Union Army. As a doctor, Augusta’s knowledge and skills were of great value to the war effort, and he immediately drafted a letter to the president offering his services:

I beg leave to apply to you for an appointment as surgeon to some of the coloured regiments, or as physician to some of the depots of ‘freedmen.’ I was compelled to leave my native country, and come to this on account of prejudice against colour, for the purpose of obtaining a knowledge of my profession; and having accomplished that object, at one of the principle educational institutions of this province, I am now prepared to practice it, and would like to be in a position where I can be of use to my race.

Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton forwarded Augusta’s correspondence to the Army Medical Board in Washington, D.C., which summarily rejected him for several reasons—his skin color foremost among them. Still, Augusta had never cowed to prejudice—whether it was encountered in learning how to read, going to medical school, or serving his native country in the fight for the Union and emancipation.

So, Augusta left Toronto for Washington, where he immediately petitioned the board. “I have come near a thousand miles at great expense and sacrifice,” he told them, “hoping to be of some use to the country and to my race at this eventful period.”

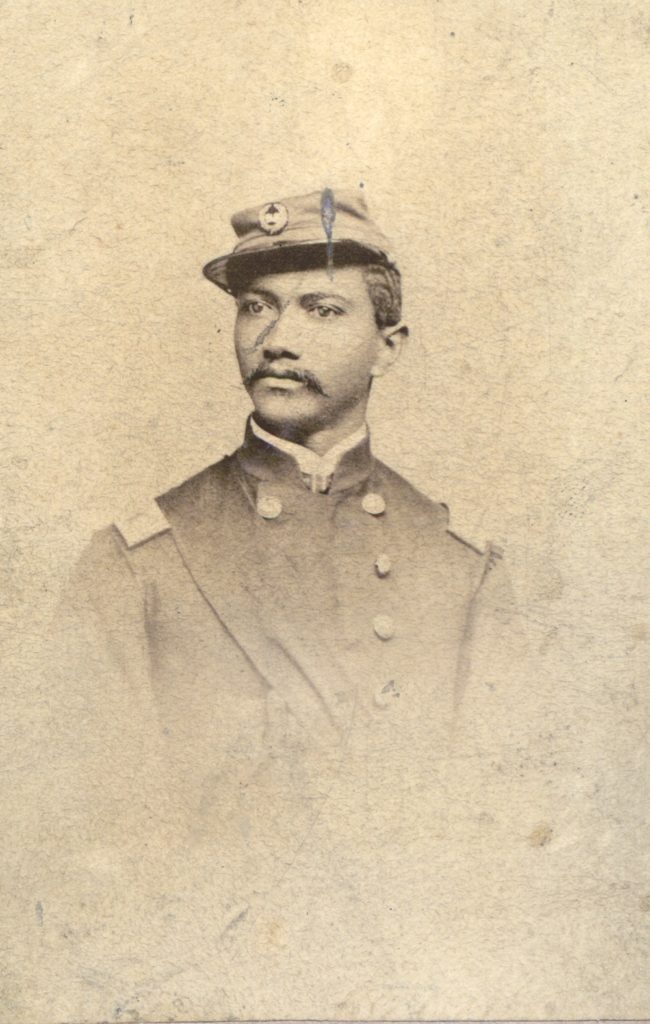

This simple statement moved the board to give the 38-year-old physician a chance at the qualifying exams. Augusta passed with flying colors and received both an appointment as the United States Army’s first Black surgeon and a commission as a major, making him the highest ranking African American officer in the U.S. military.

Two days later, Augusta created a stir in Washington at a reception celebrating the first anniversary of the freeing of the slaves in the Union capital. As a reporter with the Evening Star observed, “The appearance of a colored man in the room wearing the gold leave epaulettes of a Major, was…the occasion of much applause and gratulation with the assembly.”

But not everyone was impressed. Some were disgusted by the sight of a “colored officer.” In May 1863, a crowd of Whites assaulted Augusta as he took his seat on a train at Baltimore’s President Street depot—one of the men cursing him before ripping the epaulettes from his uniform. Furious, Augusta reported the incident to the provost marshal, whose men managed to arrest a handful of the perpetrators.

Other similar indignities followed, all of them constant reminders of the country’s systemic racism. Throughout the following year, Augusta encountered numerous instances of discrimination, insubordination from White enlisted men, and even acts of disdain on the part of civilians; perhaps the most humiliating of them occurring in 1864.

In February, Augusta was on “detached service” from his original unit, the 7th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops, working as senior surgeon at Camp Stanton in Maryland. On February 1, he had to be in nearby Washington to give testimony in a court-martial regarding the murder of a Black man. That morning, he left his home in a torrential downpour, and hoping to remain dry, hailed a streetcar.

As Augusta later recalled: “[W]hen I attempted to enter, the conductor pulled me back and informed me that I must ride on the front as it was against the rules for colored persons to ride inside. I told him I would not ride on the front, and he said I should not ride at all. He then ejected me from the platform, and at the same time gave orders to the driver to go on. I have therefore been compelled to walk the distance in the mud and rain, and have also been delayed in my attendance upon the court.”

The incident garnered widespread attention, especially with abolitionist lawmakers such as Charles Sumner, who addressed the matter during a Senate floor debate.

The significance of these events, however, isn’t simply in what they said about Augusta’s strength of character, but also what they revealed about the United States at the close of the war.

Success stories like Augusta’s were largely the result of a perfect storm of human qualities—penetrating intelligence, fearlessness and determination, persistence, and a healthy sense of righteous indignation.

Augusta should not have had to fight so hard to achieve what he did, and that spoke volumes about the racial problems that ultimately went unaddressed, even in the wake of a conflict that killed more than 600,000 people.

After Augusta mustered out a breveted lieutenant colonel in 1866, he continued to fight for his own betterment and that of thousands of other African Americans. In September 1868, he joined the faculty of Howard University’s Medical School, becoming the first Black professor of medicine in U.S. history. In the coming years, he also continued in private practice, founded the nation’s first African American medical society, and helped lay the foundation for what would eventually become the National Medical Association.

He died in December 1890 at age 65, his headstone at Arlington bearing mere traces of the full life he lived.

Michael Williams is a Maryland-based writer and historian. He is currently working on a book about the untold story of Rebel Baltimore, General Lew Wallace, and a detective who saved the Union.