Our story begins in the company of the Right Honorable Christopher Birdwood Thomson, First Baron Thomson of Cardington, Privy Councillor, Commander of the British Empire, peer of the House of Lords, ex-brigadier, ex–General Staff, ex-Cheltenham, ex-Woolwich, ex–Royal Engineers, ex–a lot of other things. His official title is Secretary of State for Air, which has a nice Shakespearean ring and is an apt description of what he does for a living. He is also, according to his lengthy dossier, a talented multilinguist, a devoted Francophile, and a writer of some note. He is exceptionally tall. He has an elevated forehead, a strong Roman nose set between frank, wide-set eyes, and an understated, late-imperial mustache.

The date is October 4, 1930.

Lord Thomson is traveling this day from London to Karachi, India, by airship, a five-thousand-mile, single-stop journey over some of the earth’s most hostile terrain that no one, lord or otherwise, has ever made. The idea is a bit crazy, in the way that experimental projects often are. But relatively few people, in this time and place, appear to think so.

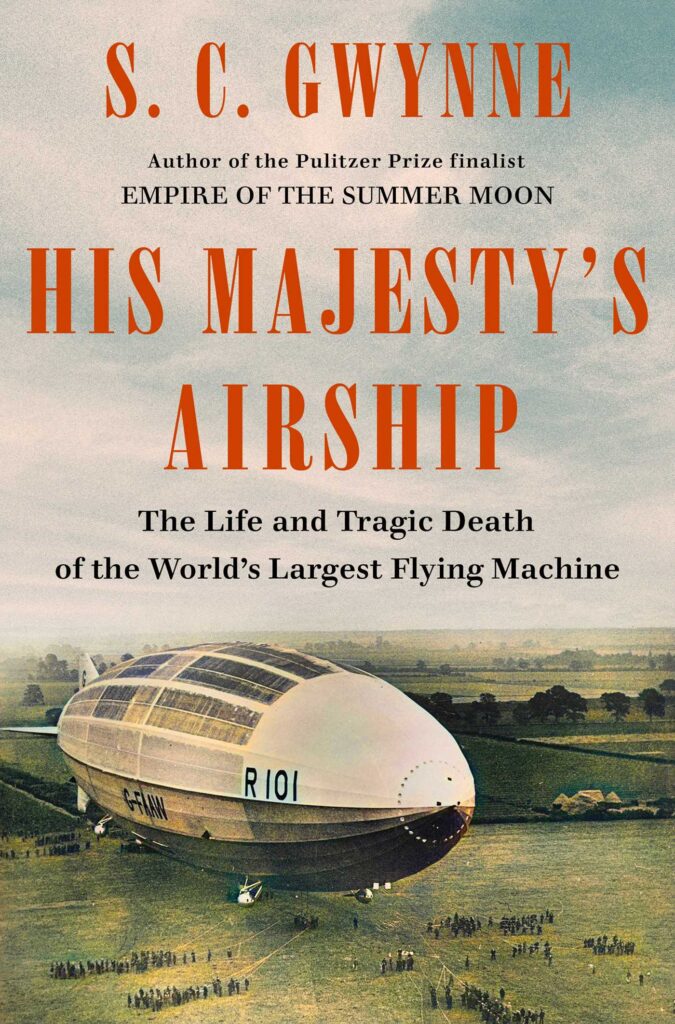

His Majesty’s Airship: The Life and Tragic Death of the World’s Largest Flying Machine

by S.C. Gwynne, Scribner, May 2023

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

Thomson must first drive from his London residence to Cardington, sixty miles north of London, a place that sounds—based on his titles and honorifics—as though it might be a Renaissance country estate in rolling pastureland. Cardington is instead a gritty little industrial suburb of the small city of Bedford. Lord Thomson of Cardington has chosen it deliberately as part of his title, just as the imperial heroes Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, Lord Roberts of Kandahar, and Lord Wolseley of Tel-el-Kebir chose theirs. But instead of a battleground of empire, Thomson is lord of a sprawling manufacturing complex—the center of the exotic world of British rigid airships.

He leaves his flat in Westminster in midafternoon and travels north in his chauffeured blue Daimler with his private secretary and valet, crossing through Trafalgar Square, Piccadilly, and Regent’s Park, thence into the gray rolling countryside of Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire.

They stop for a cup of tea in Shefford.

Near Bedford, the Daimler climbs to the top of a hill, from which the city and its Cardington suburb are visible on the level plain below. Thomson, who has been deep in his ministerial papers during the drive, asks the driver to stop. Thomson unfolds himself from the car, all six foot five of him, in Savile Row overcoat, homburg, and neatly folded pocket handkerchief. He crosses the road and gazes over the farmland toward Cardington, where, two miles off, his eyes come to rest on an astounding sight. He has seen it before, but never from this distance, and the experience of wonder is the same every time he sees it. Secured to a 180-foot mooring mast, nose-to in a rising southerly breeze, floats the silvery form of an object larger by volume than the Titanic: His Majesty’s Airship R101—in the vernacular “R hundred an’ one.” Even from here, there is something implausible and physical-law-defying about it, a giant silver fish floating weightless in the slate-gray seas of the sky. One of the largest man-made objects on earth is lighter than the air through which it glides. The ship is flanked by two equally gigantic airship sheds, so huge they loom like medieval cathedrals over the spreading farmland.

Thomson gets back in the car, and they descend through the gathering dusk and rising wind to the Royal Airship Works in Cardington. The time is just before 6:00 p.m. The 777-foot-long, steel-framed, linen-draped, hydrogen-filled airship, with fifty-four aboard, is set to leave for India within the hour.

Despite his Cheltenham manners and ministerial calm, Christopher Birdwood Thomson is a man obsessed. He has been the driving force behind a scheme to connect the far-flung outposts of the British Empire through the new medium of the air. He has taken firm hold of the national building program whose purpose is to show the world that it can be done. Flying R101 to India will be the proof. R101 is his baby. Or perhaps more accurately, the spawn of his gauzy, rainbow-inflected vision of a future in which fleets of lighter-than-air ships float serenely through blue imperial skies, linking everything British in a new space- time continuum.

“Travelers will journey tranquilly in air liners to the earth’s remotest parts,” Thomson has written, “visit the archipelagos in southern seas, cruise round the coasts of continents, strike inland, surmount lofty mountain ranges, and follow rivers as yet half unexplored from mouth to source. . . . They will obtain a bird’s-eye view of regions made inaccessible hitherto by deserts, jungles, swamps, and frozen wastes . . . high above the mosquitos and miasmas, and mud and dust and noise. By means of the airship man will crown his conquest of the air.”

These were extravagant promises. But in the fall of 1930, when airplanes are still uncomfortable, dangerous, and in constant need of refueling, Lord Thomson’s vision seems entirely plausible. Planes are short-hoppers, the Lindbergh miracle notwithstanding. Oceangoing ships are irremediably slow. Airships, on the other hand, can span empires, specifically the one belonging to the British, which has grown by a million square miles and 13 million souls since the end of the Great War. “I always fancied the dirigible against the aeroplane for the overhead haulage in the years to come,” wrote Rudyard Kipling, reflecting the fashionable thinking of the day. If Lord Thomson can’t bring the imperial dominions, mandates, protectorates, colonies, and territories closer in space, he can bring them closer in time, which is really the same thing. The interval required for global travel—with regular passenger and mail service—can be reduced from oceangoing weeks to airborne days.

In 1927 a British air minister named Samuel Hoare flew by airplane from England to India to show how easy and practical it was. He instead proved the reverse, at least to airship promoters such as Thomson. Hoare’s 6,124-mile journey in a de Havilland Hercules trimotor required twelve bone-rattling days and twenty stops. By comparison, an ocean liner can make the passage in two weeks. R101 can do it in four days, with one stop. The king-emperor of England could be in Canada one week, Australia the next, South Africa the next. Why not?

Thomson, moreover, as secretary of state for air, is the perfect man for the job. He is a fully formed creature of empire: born of it, raised into it, a disciple of the not-quite-yet-out-of-date idea that it is the white man’s destiny to rule. He has spent large chunks of his career fighting for it in South Africa, West Africa, and the Middle East. In the coming days he will fly over parts of the empire he helped create. R101’s single stop will be in British-controlled Egypt, by the Suez Canal, lifeline of the empire. The symbolism is impossible to miss. As Thomson himself wrote in 1927, linking the empire by air “will not only confer air power, it will also consolidate the Empire, give unity to widely scattered peoples unattainable hitherto, create a new spirit or, maybe, revive an old spirit . . . and inculcate a conception of common destiny to the mission of our race.”

But even deeper purposes are working here. Thomson’s destination this day—India—is not only the shimmering jewel of the British Empire, where 150,000 Britons still rule outright over more than 300 million Indians, but also a die-hard imperialist’s idea of what twentieth-century imperialism ought to look like. India is also the place where Thomson was born. Though he left India for England as a child, he still feels India’s deep pull.

His voyage has been carefully arranged to coincide with the Imperial Conference in London—a meeting of the eight dominion premiers—where the future of the empire, and specifically the future of airships, will be discussed.* Thomson’s trip is thus a piece of stage management on a global scale, a public relations stunt unseen before, even in the gaudiest days of empire. If all goes well, he will make his ten-thousand-mile round trip along the most imperial of all routes, returning to England trailing clouds of glory, having proven his theory just in time to deliver a paper on the future of airships to the conference. If he succeeds, he will be rewarded with more money and more airships and the opportunity to play out his grand vision. The newspapers have already reported rumors that the new viceroy of India will be named at the end of the conference. Thomson is the betting favorite.

Thus R101, en route to India on October 4, 1930, carries more than just her crew and cargo. She is by design a ship of empire. She has been built that way and promoted that way, and succeed or fail she bears with her the dreams not only of Christopher Birdwood Thomson but of millions of other people, too.

Excerpted from “His Majesty’s Airship” by S.C. Gwynne. Copyright © 2023 by Samuel C. Gwynne. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.