British Field Marshal Sir John Greer Dill’s funeral on Nov. 8, 1944, prompted a flood of tributes, an uncommon outpouring in wartime Washington D.C. Orchestrated by U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, the observances included a memorial service in Washington National Cathedral, a motorized cortege along a route flanked by thousands of soldiers and interment in Arlington National Cemetery. The British field marshal’s devotion to the Allied cause was also recognized by a rare joint resolution of Congress and posthumous award of the U.S. Army’s Distinguished Service Medal.

Six years later, on Nov. 1, 1950, high-ranking military and government officials again gathered at Arlington to honor Dill, and President Harry S. Truman and Secretary of Defense Marshall unveiled a statue of Dill on horseback atop his grave—an honor accorded only one other soldier interred in the national cemetery, namely Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny, hero of the Mexican War and American Civil War. General of the Army Marshall was never one to lavish praise, but he offered this stirring eulogy:

Here before us in Arlington, among our hallowed dead, lies a great hero, Field Marshal Sir John Dill. He was my friend, I am proud to say, and he was my intimate associate through most of the war years.…I have never known a man whose high character showed so clearly in [the] honest directness of his every action. He was an inspiration to all of us.

From January 1942 until his death in November 1944 Field Marshal Dill headed the British Joint Staff Mission, representatives of the British Chiefs of Staff permanently based in the U.S. capital. He was also the senior British member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, military leaders of both countries who developed strategy and allocated resources for coalition warfare against Germany and Japan.

But Dill’s actual role went far beyond his charter. A trusted colleague of the U.S. service chiefs, particularly Marshall, the field marshal was a valued facilitator, a conciliator and a keen interpreter of each country’s aspirations. The sometimes strained alliance would have been far rockier had Dill not been able to furnish rationale for rival points of view and assist in crafting much-needed compromises.

Dill’s journey to America was more happenstance than part of a grand plan. He had been chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), with oversight of the British army, since May 1940, though he never gained the confidence of Winston Churchill. The prime minister referred to the reserved general as “Dilly Dally,” hardly a term of endearment, and when Dill reached the official retirement age of 60, Churchill wasted no time replacing him. In November 1941 the prime minister announced General Sir Alan Brooke would be the new CIGS. He had Dill promoted to field marshal and appointed him governor-designate of Bombay, India, intending to put him “out to pasture.”

Within weeks the December 7 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II. On December 11 Germany declared war on the United States, and the next morning Churchill embarked for the United States aboard the battleship HMS Duke of York for talks with Franklin D. Roosevelt. He wanted to ensure that defeating Germany would be the top U.S. priority. Charles Wilson, 1st Baron Moran, the prime minister’s acerbic personal physician, candidly remarked, “Mr. Churchill has been panting to meet the president.”

Churchill and his staff of 80 arrived on December 22. As General Brooke remained in London, the prime minister drafted Dill to attend the conference, code-named Arcadia. Churchill took up residence in the White House, the conference dragging on till Jan. 14, 1942. He was oblivious that his eccentric habits, including regular daytime naps and working into the early morning hours, inconvenienced his hosts.

Arcadia set the initial tone of the bilateral relationship. From the outset Churchill demonstrated a propensity to talk more than listen and projected the aura it was he who would lead his new ally to victory. At the same time his military advisers’ overweening self-confidence, bordering on arrogance, offended their American counterparts. It was not a good start.

On the positive side, Churchill’s interaction with Roosevelt did reaffirm the “Germany first” strategy. He also gained presidential approval to establish the office of the Combined Chiefs of Staff in Washington, D.C., with Dill as Britain’s primary military representative.

During Arcadia and in the weeks that followed, Americans pressed for an immediate “second front” in northern Europe, to get into the fight against Germany and take pressure off ostensible ally the Soviet Union, whose survival remained in question. To mount a cross-channel invasion before the United States had fully mobilized was unrealistic, yet the prime minister acted as though he supported such a premature move.

British historian Max Hastings lent some context for such duplicity in his 2009 biography Winston’s War. In it Hastings quotes a cable from Churchill to Roosevelt, in which the prime minister states, “Arrangements are being made for a landing of six or eight divisions on the coast of northern France early in September.” The assertion was a blatant fabrication.

According to Hastings, Churchill was disingenuous because he feared candor might prompt the United States to shift the axis of its war effort to the Pacific, an option strongly advocated by U.S. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King. But such evasion on the part of the prime minister created lingering distrust among the American chiefs. For his part, Marshall, who would emerge as the primary architect of U.S. strategy, came to trust only one of his British counterparts—Dill.

The Marshall-Dill bond grew stronger as Anglo-American debates became more acrimonious. Dill worked to dampen inflammatory rhetoric and find common ground among the Allies. Confidence in the field marshal’s abilities also grew among senior civilians, including Harry Hopkins, Roosevelt’s closest adviser.

With Marshall’s approval, Dill shared selected American message traffic with the British Chiefs of Staff to provide keener insight into U.S. concerns. General Brooke saw the value of the back channel and furnished similar documents. Brooke became a strong advocate of the field marshal and touted his worth to a skeptical prime minister.

Shipping constraints, shortages in landing craft and recognition of their lack of preparedness forced Americans to postpone the second front and instead strike the Germans in North Africa with Operation Torch. Roosevelt, ever the politician, wanted Torch to start before the Nov. 3, 1942, midterm elections and was disappointed when problems delayed the landings until November 8.

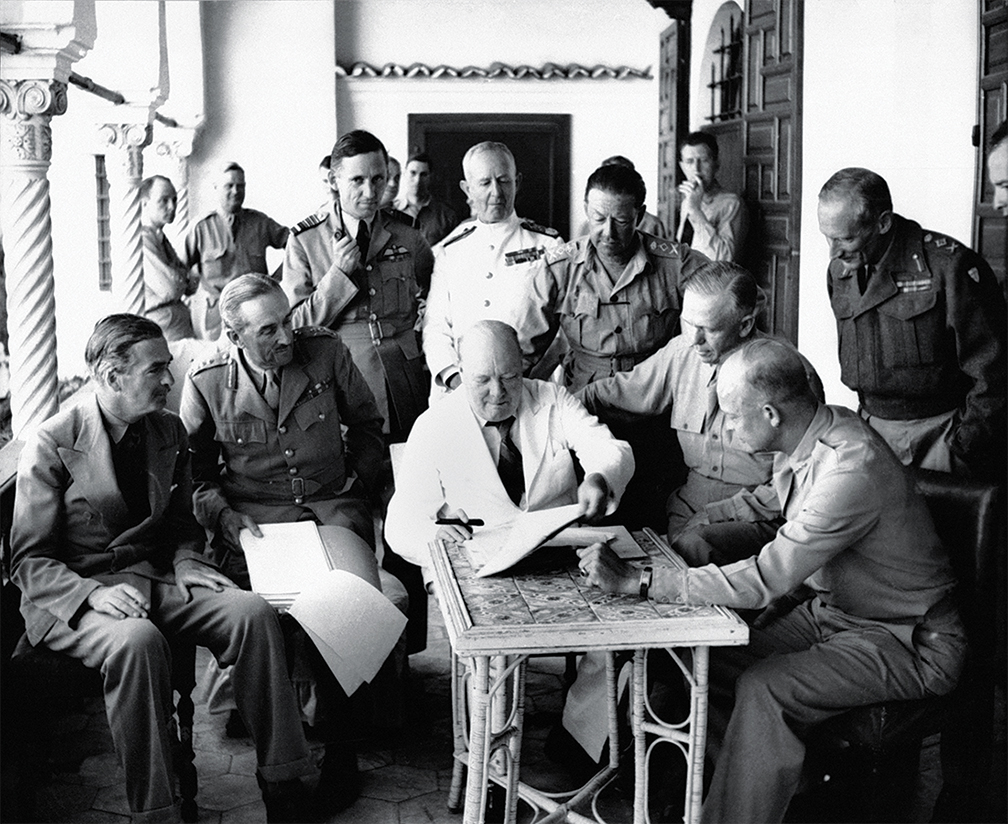

Successes in North Africa generated a series of conferences to determine “where to go from here.” There were five meetings in 1943—in Casablanca (January 14–24), Washington, D.C., (May 12–25), Quebec (August 17–24) and Cairo-Tehran (November 22–December 7). Joseph Stalin only attended the Tehran Conference, the first face-to-face meeting of the “Big Three” Allied leaders of the United States, Britain and the Soviet Union.

Churchill loved “summits,” his word for major conferences, for they gave him a stage and a captive audience for his monologues advancing the British agenda. He was irked when Roosevelt rejected his recommendation to hold one of the gatherings in London.

Casablanca proved a useful venue in which to plan the next campaign and visit battlefield commanders. Churchill basked in the recent British victory at El Alamein, Egypt, and his status as the alliance’s senior partner. Although the United States had 150,000 soldiers in the region, Britain had three times as many men, four times as many warships and an equal number of combat aircraft. Thus Churchill had a big bargaining chip when it came time to determine where to employ forces after Torch.

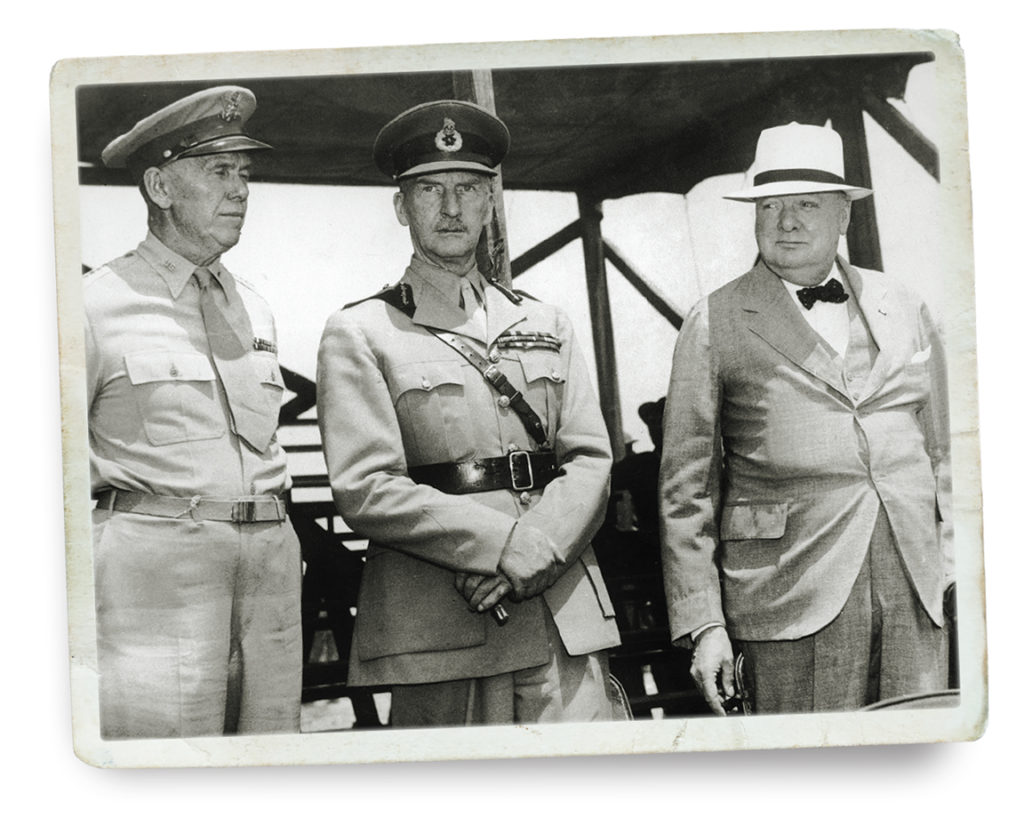

Roosevelt limited the size of the U.S. delegation, which proved a self-inflicted wound. In contrast, the British brought a full complement of planners and a communications ship to allow immediate contact with the remainder of the staff back home. They were better prepared and able to respond quickly to counterproposals. Fortunately for all concerned, Marshall had the foresight to include Dill as a guest in the U.S. contingent.

The British raised major concerns about the scale of the U.S. buildup in the Pacific and postulated that a bombing campaign against Germany might relegate the invasion of France, in 1945 or later, to a mopping-up exercise. Their suggestion to delay the cross-channel invasion was anathema to Americans and put the Allied contingents at loggerheads.

Dill brokered a compromise that endorsed a credible commitment in the Pacific, a combined bomber offensive against Germany, an invasion of France in 1944 and a landing on Sicily in the summer of 1943. He shrewdly reminded Brooke that neither side wanted to hand unresolved issues to Churchill and Roosevelt, knowing “what a mess they would make of it.”

Dill’s efforts proved so significant that Roosevelt personally thanked him. In an unprecedented gesture, Marshall invited the field marshal to bring his wife to the United States and offered him a house on “Generals’ Row” at Fort Myer, Va. Lady Nancy Dill became very popular in Washington society and repeatedly popped up in news accounts wearing her Red Cross uniform and doing volunteer work.

Meanwhile, Dill sent home detailed reports about the United States’ growing strength. In 1943 American forces reached 10.5 million men under arms, with 4 million overseas and another 6.5 million in training and soon to deploy. In comparison, by year’s end British manpower topped out at 3.8-plus million. After that, the replacement of casualties proved problematic, though Brooke and fellow chiefs went to great lengths to minimize the degraded state of their armed forces.

As the agreements at Casablanca failed to address actions after Sicily, Churchill pressed for another conference to settle that question. He already had the answer—Italy, what he called “the soft underbelly of the Axis”—and was confident his powers of persuasion would convince Roosevelt. Based on intelligence intercepts, Churchill believed the Germans would not defend the peninsula if Italy were knocked out of the war. That turned out to be an incorrect assumption.

The American chiefs could not afford to have their troops in North Africa and Sicily sit idle, thus a modest commitment in Italy was a logical course of action. If Adolf Hitler did resolve to staunchly defend Germany’s ally in the Mediterranean, Marshall would limit the campaign, as it would consume an inordinate amount of men and equipment, delaying the cross-channel operation. He suspected the latter outcome was the British game plan all along. The chief of staff emphatically stressed Italy would not be a decisive theater, and fighting on the periphery of the Nazi regime would not bring victory.

Churchill always viewed his commitments as flexible, particularly the 1944 date for Overlord, code name for the cross-channel attack. He lobbied for delays and advocated other ventures to weaken Germany. After the May 1943 conference in Washington, D.C., U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson felt so strongly about British prevarication that he sent Roosevelt the following assessment:

[The] prime minister and his chief of imperial staff are frankly at variance with such a proposal [Overlord]. The shadows of Passchendaele and Dunkerque [sic] still hang too heavily over the imagination of these leaders.…Though they have rendered lip service to the operation, their hearts are not in it.

Stimson and Marshall were ultimately able to convince Roosevelt that Overlord, coupled with an invasion of southern France (initially code-named Anvil, later Dragoon), must be initiated as soon as possible.

Prior to the August conference in Quebec Dill warned the British delegation the Roosevelt administration was under increasing pressure from Congress, which questioned why the United States seemed to follow British plans when the former was picking up most of the cost of the war. The criticism came from members of both parties and worried Roosevelt.

Senator Arthur Vandenberg, a Michigan Republican, for one suggested operations in the Mediterranean had been initiated to maintain Britain’s lifeline to India, not to defeat the Wehrmacht. Vandenberg was reflecting the general opinion of the American public, which viewed Churchill and Britain with growing disapproval. Even the Soviet Union ranked higher in popular esteem. British stock further eroded when it was publicized that 9,000 of its military personnel and civil servants were serving in Washington, D.C. The days of admiration for the island nation standing alone against the Nazi juggernaut were long past.

Even in the face of mounting U.S. disapproval, Churchill was unable to contain his flights of strategic fantasy. Throughout 1943 the prime minister requested additional resources for Italy, cited the benefits of operations in the Balkans, extolled the advantages of striking toward Vienna through what he called the “Ljubljana Gap” (an area between two mountain ranges in northern Yugoslavia) and proposed amphibious assaults in the eastern Mediterranean. Roosevelt found Churchill’s hit-or-miss approach tiresome and showed little interest in discussing the schemes. He sarcastically equated the Ljubljana Gap fixation to Churchill’s earlier pronouncement that Italy was the soft underbelly of the Axis. It proved far from soft.

When Roosevelt and Churchill arrived in Cairo as a precursor to meeting Stalin, there was a noticeable change in personal dynamics. Roosevelt, conscious of America’s emergence as the stronger partner, was visibly distant to the prime minister. The president insisted on inviting Chiang Kai-shek, incensing Churchill, who saw China’s participation in the war as inconsequential. Roosevelt added another slight when he cancelled their final one-on-one meeting before leaving for Tehran.

In order to revive his Mediterranean strategy, Churchill tried to convince Marshall that an invasion of Rhodes, the largest of the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean Sea, would aid the war effort and bring neutral Turkey into the conflict on the Allies’ side. Following the president’s guidance, an irritated Marshall replied, “Not one American soldier is going to die on [that] goddamned beach!” His brusque response shocked Churchill and further emphasized the United States’ emergence as primus inter pares (“first among equals”). The prime minister blamed Dill for what he considered American intransigence.

At the first session in Tehran Stalin waved aside Chur-chill’s lengthy introductory remarks and bluntly asked to get down to business. The Soviet generalissimo made it clear Overlord and Anvil were the keys to victory over Germany. He discounted fighting in Italy and forays into the eastern Mediterranean as having little effect on the war’s outcome. Roosevelt and Stalin called the shots and set the spring of 1944 as the date to launch both operations. The prime minister’s attempts to delay the cross-channel attack and cancel the assault on southern France seemed to be thwarted.

Shortly after the Tehran Conference adjourned, the British renewed efforts to expand operations in Italy, augmented by a tenuous beachhead at Anzio. They sought to scrub Anvil and break the stalemate on the Italian peninsula by using shipping from the Pacific to reinforce the lodgment. The American chiefs acknowledged landings in southern France had to be delayed until August 1944, but they refused to move landing craft from the Pacific unless earmarked for Anvil. Tempers on both sides of the table reached new heights.

Dill was again thrown into the breach as an honest broker. He explained to the British chiefs Roosevelt was facing domestic criticism for his perceived neglect of the Pacific. Slowing operations there by withdrawing vital landing craft for employment in a secondary theater was unpalatable, especially in a presidential election year.

Dill’s labors earned him additional enmity from the prime minister, who continued to decry Anvil and bombard American officials with telegrams requesting more resources for Italy. In a fit of irrationality, he even accused the field marshal of having been “Americanized.”

Increasingly concerned Churchill might recall his British colleague, Marshall set about building a “backfire” that included arranging to have Dill awarded Yale University’s prestigious Howland Memorial Prize for his invaluable contributions to international relations. Honorary degrees from Columbia and Princeton followed. The accolades garnered extensive press coverage, possibly staying Chur-chill’s hand from recalling or censuring his representative.

Dill’s DSM

In 1944 the United States recognized Dill’s wartime service with a posthumous Distinguished Service Medal. Supporting paper-work noted his “enduring contribution toward the victorious conclusion of the war and also to that harmony of purpose…essential to our security.”

The Anvil dispute was the last contentious issue Dill was able to mediate. In the summer of 1943 he was diagnosed with aplastic anemia, a rare disorder in which the body fails to produce blood cells in sufficient numbers. For a year doctors kept him alive with blood transfusions, but in June 1944 Dill collapsed just prior to accompanying the U.S. chiefs on a visit to Normandy. He endured an extended hospitalization and a long convalescence but never fully recovered. Dill died at Walter Reed General Hospital in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 4, 1944.

The response in London to the field marshal’s passing was muted, Churchill neglecting to mention it either in Parliament or on the radio. In a note to the prime minister, Marshall chided his indifference. “Few will ever realize the debt our countries owe [Dill] for his unique and profound influence toward the cooperation of our forces,” he wrote. “To be very frank and personal, I doubt if you or your cabinet associates fully realize the loss you have suffered.” Belated recognition came from Brooke in his wartime diaries. In its pages the British chief readily skewered such senior officials as Churchill, Roosevelt, Marshall and King, but the words he reserved for Dill were glowing. His was a lone voice throughout the British empire.

In his multivolume biography of Marshall author Forrest C. Pogue succinctly captured the value of Dill’s contribution to the war effort:

In an amazing balancing act, Dill was able to represent British wishes to the Americans without antagonizing them and to warn London of the limits of American forbearance without arousing suspicion on the part of his own chiefs that he had become a captive of his hosts.

General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, supreme Allied commander in the Mediterranean, was promoted to field marshal and appointed to replace Dill. Known as “Jumbo” due to his girth and affability, Wilson made every effort to fill the shoes of his late colleague but never achieved Dill’s deft touch or sense of timing. Fortunately for the Allied effort, after November 1944 they had settled their major strategic differences, and operational issues were not as divisive as they had been when Sir John Dill proved practically irreplaceable.

John Howard served in the U.S. Army for 28 years, retiring as a brigadier general. He was a combat infantryman in Vietnam. For further reading he recommends Very Special Relationship: Field Marshall Sir John Dill and the Anglo-American Alliance, 1941–44, by Alex Danchev.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.