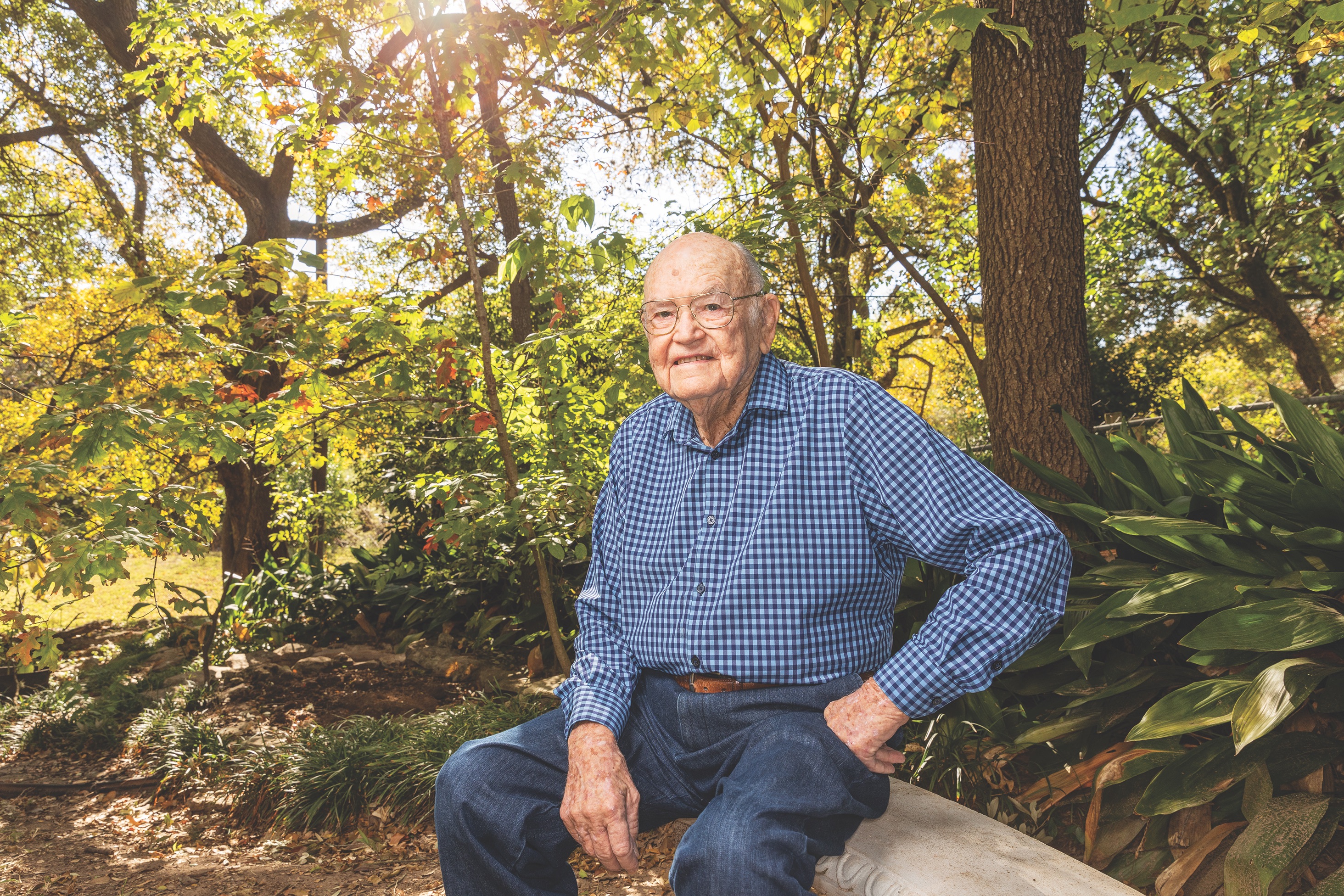

The retired lieutenant colonel recalls his days spent at England’s Duxford Air Force Base—and in the sky.

IN LATE 1942, Huie Lamb withdrew from the ROTC program at Texas A&M University to enlist as a flight cadet: the 18-year-old, born in Carey, Texas, wanted to fly. After graduating through a series of flight schools and earning the coveted wings of a U.S. Army Air Forces aviator, he shipped overseas to serve as a pilot with the 82nd Fighter Squadron, 78th Fighter Group. During his time in Europe, Captain Lamb flew P-47s, as well as P-51s, and became one of the first pilots to shoot down a German Me 262 jetfighter. He went on to survive 61 combat missions, along with a crash into the English Channel when his P-51 suffered mechanical failure. From his home in Texas, Lamb—who retired from the Air Force as a Lieutenant Colonel in 1984 and who will turn 97 this February—recalled his time flying out of the American base at Duxford, England, and what it was like to be a fighter pilot in a dogfight.

Before we talk about the dogfights, let’s talk about the bar fights. What were you guys doing for entertainment when you weren’t flying?

Usually we would get a weekend pass and go to London. We’d go there and meet girls. We enjoyed getting away. There were a lot of buzz bombs hitting London, and then the V-2s—that wasn’t any fun. There was also a troop carrier truck that would go into Cambridge [about 12 miles from Duxford]. There was a place called Dorothy’s or something, and we’d go there to dance, and then we’d take the troop carrier back.

Some guys had bicycles. When we first got over there, they gave each of us in the 82nd Fighter Squadron a bicycle. Well, those crazy guys started riding those bikes like they were airplanes and tried to outdo each other. We had accidents, and guys would get hurt. So the commander said, “Get rid of those bicycles.” And they wouldn’t let us have them anymore.

Tell us about your first aerial victory.

In that business, they say that you “learn as you go.” We were on an escort mission over Germany—I think Colonel Joseph Myers was leading the group with one of the squadrons at a higher altitude. We in the lower squadron were a bit separated from them. Myers radioed us: “Come on up! ‘Cause there’s a gaggle of German planes heading for the bombers.” It wasn’t a formation like we were in—it looked like there were hundreds of them. “Come on up,” Myers said, “We got ’em cornered.”

I was “tail-end Charlie,” which means I was the very last guy, on the right side of the formation. About that same time, I looked over and there was a Me 109 fighter. I could see his guns flashing—he was shooting at me! I immediately called it over the radio and turned into him, circling to get on his tail at 29,000 feet. He dropped his flaps and his landing gear, hoping I would overshoot him. Well, I didn’t have time to even get a shot at him, so I pulled up and did a wingover to come back around. But my element leader shot him down first.

About two weeks later, on October 12, 1944, something similar happened. I was a wingman, and there was a lone 109 flying fairly low to the ground—about 2,000 feet. My element leader made a pass at him but was going so fast he overshot him and missed. By that time, I learned that you had to kind of slow down, so I reduced speed and was able to hit him. The 109 went straight in—it wasn’t really much of a fair fight. He didn’t have a chance, really. But he would’ve done it to us if he could have.

Just three days later, you became one of the first pilots to shoot down a German Me 262 jet.

We were flying a strafing mission to hit marshaling yards in Germany; I was wingman to Captain John Brown, who’d flown with the Royal Air Force in one of the “Eagle Squadrons” [fighter squadrons consisting of volunteer American pilots] early in the war. He joined the 78th Fighter Group when the squadrons became part of the U.S. Army Air Forces. We’d shot and destroyed maybe four or five locomotives, and after about 30 minutes, John said, “Let’s head back.” He had a saying: “Fight and run away, live to fight another day.”

So we were leaving the area about 15 or 20 minutes earlier than the other guys. We were at about 15,000 feet, and I saw a bogie down at about 1,000 feet. I alerted John, who looked but couldn’t spot it. He replied, “You check it out, and I’ll cover you.” That’s all he had to say. I dove, and my airspeed indicator read 475 [mph], but I wasn’t gaining on him. So I hit the water injection [to briefly boost the engine’s horsepower], and it gave me about another 15 or 20 miles per hour. But I still wasn’t gaining on him. So I lobbed a few rounds in front of him, and that must have alerted him, or maybe he saw me. He turned to the left, and when he did, I was able to turn inside of him to close in and catch him.

I kept shooting and hit him on the turn. He straightened out, but by that time, I was right behind him. He led me up a flak corridor to his air base—I didn’t know that until later. I wound up with only one or two of my guns firing because I had already used up a lot of ammo. I was within 100 feet, probably—I was awful close to him—and I hit his left engine. We were about 100 feet above the ground at that time, and his plane flipped on its back and exploded. After he crashed, I pulled up, and then antiaircraft guns from the air base opened up on me.

John saw this and radioed, “Get down! You’re over an airfield!” So, I went back down and came out real low, as low as I could. I finally got away from the area and was able to pull up. The flak hit my tail, so I didn’t have rudder control—but you don’t really need that for flying straight and level. I had promised my crew chief that if I got anything, I’d do a victory roll over the base back at Duxford [about 400 miles away]. But I thought better of that. Without rudder control, I settled for just getting the thing on the ground.

You had initials painted above the victory markings on your plane. Whose were they?

The first swastika had “FLW” over it, for my flight instructor, Fred Webster. When I graduated from flight school, he told me, “Get one for me!” So, I did. The second had “BL” above it, for [Lieutenant] William “Bill” Lacy. He was shot down in September 1944, probably while strafing.

You must have lost other friends.

Yes, several, including my roommate, Second Lieutenant Troy Eggleston. He’d gone to London and got a little white-haired terrier. Troy named him “Brussels” because he was such a little sprout. He became our squadron mascot.

In November 1944, they were putting steel matting down on our base because it was too muddy, so we were bussed over to Bassingbourn—the 91st Bomb Group field—where the taxiways were paved. I was taxiing out on a mission, and I got off the taxiway and into the mud. I tried to blast my way out, and when I did, my prop hit the ground. A tow truck had to pull me out, but the prop was nicked, so I couldn’t fly. Troy was on that flight, and they got into a heck of a dogfight over Germany. Troy was killed. He was an excellent pilot and an excellent gunner. He’d already shot down some German planes.

You engaged a second German jet. Tell us about that.

We were given a mission to hit a German airfield, hopefully before they could take off to go after our bombers. It was March 19, 1945. I was an element leader, and our flight leader got one Me 109, then he hit an Arado 234 [a jet-powered bomber used for reconnaissance]. We were at low altitude—about 1,000 feet. I came in and finished it off—getting several strikes on his left side. I overshot him and looked back to see him crash into the ground.

That day we got quite a few destroyed in the air, but we did lose some guys. I’ve forgotten how many.

What became of Brussels?

I’d made arrangements to bring him home. I was going to take him to Walters, Oklahoma, as a gift to Troy’s parents. Just a few days before I was supposed to depart, Brussels disappeared. I don’t know what happened to him. If somebody got him, or if he run off, I don’t know. ✯

This article was published in the February 2021 issue of World War II.