They were well-trained medical professionals. Their job was not for the squeamish. They cleaned up and repaired the corporeal mess that modern weapons made—the terrible burns, severed limbs, perforated bowels, broken bones, entry and exit wounds, internal bleeding, collapsed lungs, flesh wounds. By its nature, the job required its practitioners to immerse themselves in the unforgettable sights and smells of human tragedy. The battle against death was grim, soul searing, never-ending. The medics knew and understood this. Their professional training had instilled thick mental armor to deal with trauma and still find a way to function.

But nothing could have prepared them for the job they confronted in mid-April 1945, at a place in the heart of Germany called Buchenwald—a place few of them had ever heard of and whose horrors none could have imagined.

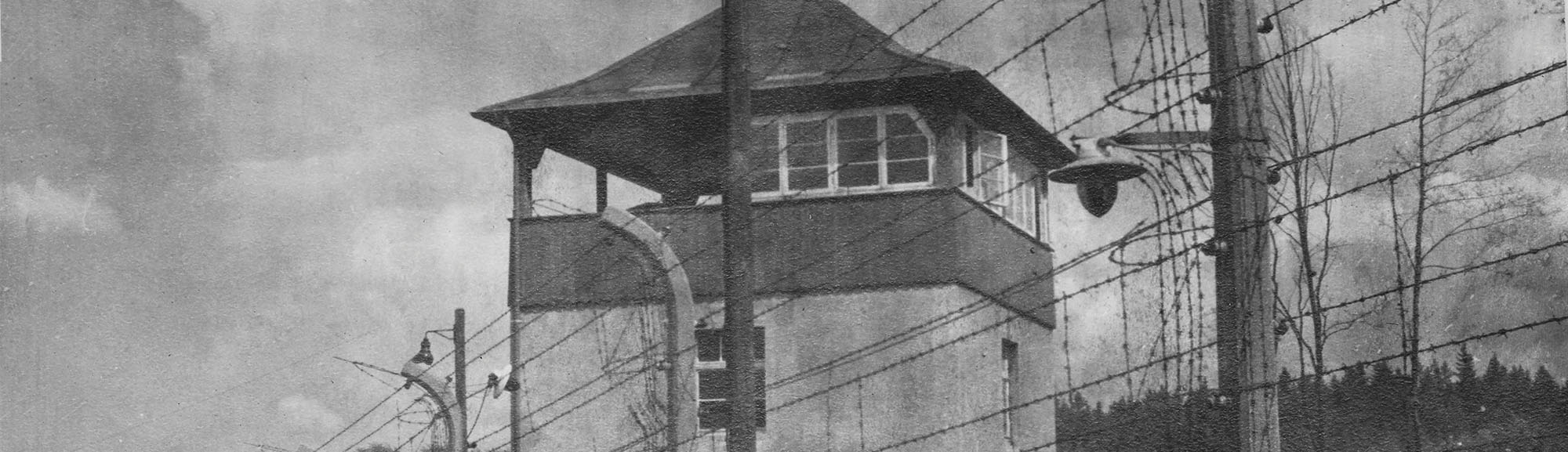

When American soldiers first arrived at the concentration camp in Weimar, Germany, they found a humanitarian disaster. Buchenwald was one of the first such camps American soldiers liberated. (The first was a Buchenwald subcamp, Ohrdruf, in Thuringia, Germany, on April 4, 1945.) Built in 1937, Buchenwald had grown into a sizable labor camp with a population of more than 21,000—about twice what its infrastructure was designed to house. By then it consisted of a main camp, with some semblance of housing, sanitation facilities, food, and a “little camp”—a barbed wire-enclosed dumping ground for transitory prisoners from all over the Nazi empire. Conditions were poor everywhere, but the little camp was especially awful. Crude tents and windowless horse stables served as shelter. Barns designed to hold 50 horses were crammed with more than 2,000 people. There was only one latrine for the entire compound. There was no running water, no heat, little food. Disease was rife. Emaciated corpses littered the ground.

A recon element of the U.S. 6th Armored Division had been first to arrive, on the afternoon of April 11, followed by soldiers of the 80th Infantry Division throughout the next day. The first medical unit—soldiers of the 120th Evacuation Hospital—arrived into this hell late on April 15. Immediately they found themselves caring for people whose physical condition was among the worst that medical personnel had ever confronted.

LIEUTENANT MAY M. HORTON, a nurse, wondered how the grateful survivors who greeted her could still be alive. They were “thin, bony, and terribly undernourished, a gaunt look. One man knelt down and kissed my combat boots. I can never think of this without tears,” she recalled. The commander of the 120th, Colonel William E. Williams, took one look at the awful conditions and decided Buchenwald was no place for Horton and the other 40 female nurses and ordered them transferred elsewhere.

Most of the SS guards who had run the place had fled; others had been beaten and taken into custody by inmates who revolted when they heard about the imminent arrival of the Americans. But the retreating SS had pulled off one final act of brutality: blowing up the camp’s sole water main. “The devilish cruelty of this action can be more readily understood when one realizes that a large number of the inmates were seriously sick, many at the point of death, and the lack of water if only for sanitary facilities was equivalent to a death sentence,” one of the physicians, Major Ralph Wolpaw, later wrote.

Many of the inmates were near starvation—a situation so desperate there was no medical protocol for dealing with it. A truck driver nicknamed Tex—“this good natured kid from Texas, friendly to everybody,” one of his buddies remembered—handed out canned C rations to the desperately hungry prisoners. But the food was like poison to their fragile systems. Several devoured the contents, passed out, and died. This terrible turn of events devastated Tex and he never fully emotionally recovered. “It has haunted him all his life,” his wife later told an interviewer; “the idea that they survived the horrors of the camp only to die there…because of what should have been an act of kindness.”

The unit initially set up a buffet-style food line for the prisoners in one of the former SS barracks. The menu included “hot meat and vegetable soup, potatoes, bread and the like,” Tec 5 Jerry P. Hontas, a surgical technician, recalled. “The food was simple in itself, but too rich for the shrunken stomachs and digestive organs of the starved men.” Several more spontaneous deaths occurred. “The lesson was quickly learned,” Hontas said. “Feeding starving people in a spirit of compassion is a task that requires patience.”

Unit records report that the menu soon changed to a “soft and liquid diet…soup, milk, oatmeal, and meat stew.” GI search parties appropriated German fare in nearby towns to augment the American food.

The medics spent roughly two days setting up a hospital in abandoned SS barracks, where conditions were initially wretched and unsanitary. They discarded the furniture, rugs, bedding, and drapery, scrubbed the tile floors and walls, and brought in new army cots and blankets scrounged from U.S. and German army stocks. Liberated inmates strong enough to work assisted the Americans.

The soldiers of the 120th then surveyed the camp to begin the job of gathering and moving those who needed medical attention away from their squalid quarters and into a clean hospital. “I was hauling desperately sick and dying prisoners, or what remained of once strong and healthy men, to the hospital,” Private Hence J. Hill wrote in a letter to his wife. “The sight of those near death was almost beyond belief—thighs the size of my arm, buttocks no longer visible, pelvic bones seen at any angle, as were other human bones. You can imagine the odor.”

Some of the surviving prisoners were children. About 900 inmates were below the age of 18 and had been housed in one overcrowded barracks amid deplorable conditions. Tec 5 Warren E. Priest, a German translator and medic, received orders to check their building and make sure no one was left. He ducked inside and was nearly overcome by the powerful stench of decay and rot. “I remember the litter everywhere, piled one or two feet high in places, making access to several parts of the barracks impossible,” he said. “Everything was covered with excrement, urine, vomit—blankets, clothing, shoes, jackets, underclothes—to call the scene indescribable is inadequate.” All of these terrible odors, mixed with the residue of burned flesh still wafting from the crematorium was, in his estimation, “beyond the human capacity to forget.”

See also: ‘This Is What Hell Is Like’: 74 Years Ago, My Grandfather-in-Law Liberated the Dachau Concentration Camp

He held his breath and briskly walked along the rows of rickety beds, past piles of debris and detritus, hoping to sweep through the vile building as quickly as possible. He reached the end, saw nothing, and turned to go back to the entrance. Just then, he noticed a slight movement amid a pile of clothing in one of the beds. His first thought was that a rat had found an appropriate home within the filth. No sooner had this thought flashed through his mind than he heard a whimper. He picked up a stick and poked the pile to investigate.

“A small child, a girl, perhaps five or six, [was] huddled in a fetal position…barely conscious,” he recalled. Astounded, he gently pulled her from the bed, wrapped her in his field jacket, took her in his arms, and rushed from the barracks. “I have to get her to the aid station as soon as I can!” he thought desperately. She was unbelievably light, so much so that he kept glancing down to make sure he was still holding her. She whimpered again and then he heard nothing. The young girl had died in his arms.

Deeply moved, saddened beyond description, defeated and discouraged, he laid her little body down. She made such an impression on him that he gave her the name Angela, to indicate that she was an angel in the middle of hell. “She lives still in my memory, that little human form…and since then she has become a constant companion of mine,” he later wrote. “Angela lives on my shoulder and close to my heart.”

BEFORE PATIENTS COULD ENTER the new wards, medics gently removed the inmates’ tattered, filthy clothing and sprayed the patients with DDT powder. In a few instances, they steam-deloused the clothes and returned them. More often they simply burned the filthy rags and scoured surrounding areas and nearby army supply depots for pajamas and other appropriate clothing.

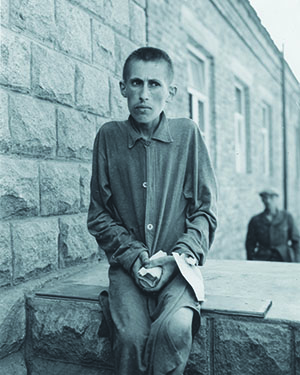

Most of the soldiers were so alarmed at the condition of their patients, they struggled to find words to describe them. “There isn’t enough flesh left to even look human,” Private Bill Whipple reported to his family in a letter. One doctor shared this sense of stunned revulsion: “At first I couldn’t believe what I saw. We were sort of horrified.” Walter C. Mason Jr., a soldier in the pharmacy section, was so staggered by the terrible state of the patients that he wondered how they could possibly have lived for a few days in such a camp, much less months or years. “Many of these patients had open sores which were covered with what appeared to me to be toilet tissue, but actually it was a type of bandage in common use there,” he later commented. “I am sure most patients were not fully aware of what was going on as each patient seemed to have that vacant stare in their eyes which made it impossible to read in their eyes any emotional reaction.”

Disturbed by the plight of so many people near death, Lieutenant John O. Lafferty, a physician, wrote to his family that “malnutrition was severe…pneumonia, scarlet fever, and every disease imaginable. There were leg ulcers, bed sores, and wounds that were not healing. Probably the average weight was not over 80 pounds.” As he indicated, diseases including typhus, dysentery, scurvy, and even tuberculosis were a significant problem. Most patients were wracked with chronic diarrhea, and this served to magnify the suffocating odor of feces, rot, and disease that seemed to engulf them like a toxic cloud.

According to the 120th’s records, the unit hospitalized and treated some 5,490 patients, with only 445 surgical cases; the rest were treated for their deteriorated physical condition and a byproduct of maladies, including 330 tuberculosis cases, 208 dysentery cases, 62 typhus cases, 49 pneumonia cases, and 98 patients with “contagion.” In some cases, the doctors administered scarce reserves of penicillin to carefully selected patients in an attempt to control infections. Seventy soldiers donated blood for transfusions. The 120th’s journal recorded 51 deaths among the hospitalized patients in a six-day period, with dozens—possibly hundreds—more dying before they could receive treatment.

The medics did their best to pick out the most severely ill patients and “try heroic measures such as transfusions, intravenous feeding and…supportive therapy in order to try to help these people to survive,” noted Captain Philip A. Lief, a physician. Besides feeding the survivors a liquid diet or soft, mild foods, they administered blood transfusions—though it was often difficult to find usable veins in the arms of such severely starved individuals. “Most of the inmates had signs of malnutrition,” Captain Lief recalled. “That meant very little skin on the face, sunken bones, eyes, eyeballs sunken in the eye sockets, very little muscle tissue on the legs or arms. One could see all the thoracic cage, the ribs very prominent. If the inmate took off his shirt, you could see the spinal column very, very prominently.”

The Americans made extensive use of any physicians among the liberated inmates. Sources do not list an exact number; there may have been around a dozen. Some of these doctors had been incarcerated at Buchenwald for years. Although they were hardly in great shape themselves, they nonetheless were in an ideal position to provide the Americans with information about the medical history of patients and, in general, assist them any way they could. They also were instrumental to the task of organizing the patients by nationality and categorizing them according to maladies and overall physical condition.

Physician James H. Mahoney recalled working with a former prisoner who had once been a preeminent surgeon in Austria. According to some of the patients, this man, whom Mahoney did not name, was such a skilled and valuable doctor that he had at times persuaded the camp authorities to afford sick inmates the kind of food, medicine, and hospital treatment the SS men received. “This surgeon’s moral and professional courage, in the face of death…remains an inspiration to me to this day,” Mahoney later said. “He was most curious about what was going on in the field of medicine in the outside world since he had been out of touch for five years.”

NURSING THE VICTIMS back to physical stability was one thing; healing their devastated mental and emotional state was quite another. The body could be replenished over time—especially for the young—with good food and decent medical care. The same might not be true of their minds. Some were suffering from acute neurological and psychological problems. Others were so traumatized and so dazed from dehydration and hunger that they hardly knew what was happening around them. Some were in such a fog and so crazed with thirst, that, in the recollection of one doctor, “they opened bottles of plasma and started to drink the plasma, although we told them this had to be given intravenously.”

Many of the patients had experienced so many months and years of dehumanizing treatment from practically everyone around them that they found it at first difficult to trust the American medics. “The mental disturbance of the inmates was very apparent,” Lief said. “It took anywhere from a week to three weeks for most of the inmates to realize the significance of the fact that they were now among friends and Americans who had liberated the camp. They were happy to see us but at first they distrusted everyone.”

When Lief and his colleagues tried to ask them about what they had gone through, they found that, psychologically at least, a part of nearly every survivor was still stuck in the horror of captivity, “living like in a nightmare. A lot of them wanted to repress what they had seen.”

Many had been separated from their families and loved ones. They wanted to know what had happened to them but the Americans, of course, could provide no information. This only deepened the sense of depression and helplessness for those patients. “They were afraid of anything and everything,” Captain Samuel Riezman, a physician, later said. As a Jewish American, Riezman felt a special sympathy for the survivors he met and treated. “I don’t think they were able to think. I felt that all of their humanity, all of their spirit, was gone. A lot of people in that condition did recuperate but, at the time, I did not see how it was possible.”

Gradually, as the inmates’ physical condition improved and they saw how hard the Americans were working to care for them, the distrust diminished—replaced by strong bonds of gratitude and friendship. “They gave us back our lives,” author and professor Elie Wiesel, a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize and one of the teenaged survivors of the little camp, once said. “And what I felt for them then nourishes me to the end of my days.”

For the medics, many of whom had seen heavy combat, the experiences of tending to the survivors of Buchenwald was especially haunting. In the years after the war, many could not speak of the camp. Others who tried to tell friends and family members, or show them snapshots, found an unreceptive, skeptical audience. Some former medics held a lifelong grudge against Germans, refusing to buy any German products or set foot in the country again. More commonly, the veterans were just deeply troubled by their glimpse into humanity’s terrible capability for cruelty and depravity.

“For many years I put it in the deepest recesses of my mind,” Tec 5 medic Harry H. Blumenthal Jr. said. “It was like an ugly scar that I wanted to cover but knew it was there and could not forget.” Like a bedeviling specter, those memories never went away. As surgical tech Jerry Hontas put it, “The only thing that vanished was our innocence.” ✯